Crossing swords with a professional philosopher can be a dangerous thing. I’m not one, of course; I simply happen to have a Ph.D. in philosophy. But Professor Edward Feser is a professional philosopher, and a formidable debating opponent, as one well-known evolutionary biologist is about to find out.

In a recent post of mine, entitled, Minds, brains, computers and skunk butts, I took issue with a recent assertion by Professor Jerry Coyne, that the evolution of human intelligence is no more remarkable than the evolution of skunk butts. (To be fair, Coyne was not trying to be offensive in his comparison: apparently he really did have a pet skunk for several years, and the simile was the first that sprang to mind for him, as a biologist.) In my post, I cited a philosophical argument put forward by Professor Feser, that the intentionality or “meaningfulness” of our thoughts cannot be explained in materialist terms, as thoughts have an inherent meaning, whereas physical states of affairs (such as brain processes) have no inherent meaning as such. However, Professor Coyne was not terribly impressed with this argument. He replied as follows:

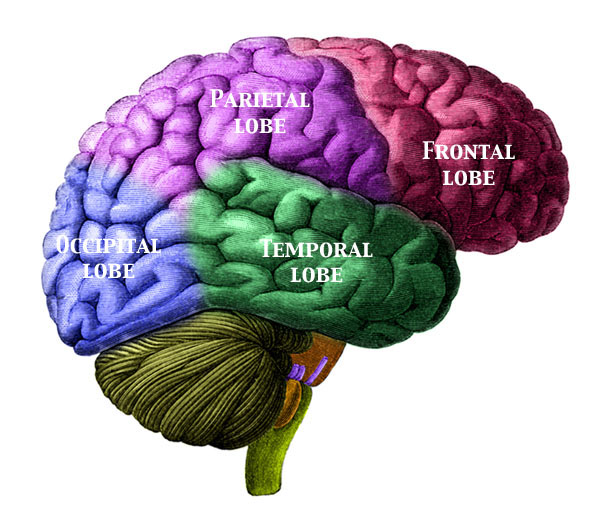

I’ll leave this one to the philosophers, except to say that “meaning” seems to pose no problem, either physically or evolutionarily, to me: our brain-modules have evolved to make sense of what we take in from the environment. And that’s not unique to us: primates surely have a sense of “meaning” that they derive from information processed from the environment, and we can extend this all the way back, in ever more rudimentary form, to protozoans.

He shouldn’t have said that.

Professor Edward Feser has just issued a devastating response to Professor Coyne over at his Website. I’d like to invite readers at Uncommon Descent to have a look at it for themselves, here. It’s a very entertaining read. Feser concludes:

… if one is going to aver confidently that “‘meaning’… pose[s] no problem,” he had better give at least some evidence of knowing what the philosophical problem of meaning or intentionality is and what philosophers have said about it.

Wise words, indeed.

Read More ›