See if you can guess which famous person wrote the following passage:

It has been the error of the schools to teach astronomy, and all the other sciences, and subjects of natural philosophy, as accomplishments only; whereas they should be taught theologically, or with reference to the Being who is the author of them: for all the principles of science are of divine origin. Man cannot make, or invent, or contrive principles: he can only discover them; and he ought to look through the discovery to the author.

When we examine an extraordinary piece of machinery, an astonishing pile of architecture, a well executed statue, or an highly finished painting, where life and action are imitated, and habit only prevents our mistaking a surface of light and shade for cubical solidity, our ideas are naturally led to think of the extensive genius and talents of the artist. When we study the elements of geometry, we think of Euclid. When we speak of gravitation, we think of Newton. How then is it, that when we study the works of God in the creation, we stop short, and do not think of GOD? It is from the error of the schools in having taught those subjects as accomplishments only, and thereby separated the study of them from the ‘Being’ who is the author of them…

The evil that has resulted from the error of the schools, in teaching natural philosophy as an accomplishment only, has been that of generating in the pupils a species of Atheism. Instead of looking through the works of creation to the Creator himself, they stop short, and employ the knowledge they acquire to create doubts of his existence. They labour with studied ingenuity to ascribe every thing they behold to innate properties of matter, and jump over all the rest by saying, that matter is eternal…

[E]ven supposing matter to be eternal, it will not account for the system of the universe, or of the solar system, because it will not account for motion, and it is motion that preserves it. When, therefore, we discover a circumstance of such immense importance, that without it the universe could not exist, and for which neither matter, nor any nor all the properties can account, we are by necessity forced into the rational comformable belief of the existence of a cause superior to matter, and that cause man calls GOD.

As to that which is called nature, it is no other than the laws by which motion and action of every kind, with respect to unintelligible matter, is regulated. And when we speak of looking through nature up to nature’s God, we speak philosophically the same rational language as when we speak of looking through human laws up to the power that ordained them.

God is the power of first cause, nature is the law, and matter is the subject acted upon.

Perhaps you may be thinking that the author is some eighteenth or nineteenth-century Christian apologist, who anticipated Intelligent Design-style arguments – maybe Rev. William Paley, or Bishop Joseph Butler, or Rev. Samuel Clarke, or perhaps even the philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Wrong, wrong, wrong and wrong! It turns out that the author was no friend of Christianity. In his own words:

The study of theology as it stands in Christian churches, is the study of nothing; it is founded on nothing; it rests on no principles; it proceeds by no authorities; it has no data; it can demonstrate nothing; and admits of no conclusion. Not any thing can be studied as a science without our being in possession of the principles upon which it is founded; and as this is not the case with Christian theology, it is therefore the study of nothing.

He was no fan of the Bible either:

Whenever we read the obscene stories the voluptuous debaucheries, the cruel and torturous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness with which more than half the bible is filled, it would be more consistent that we call it the word of a demon rather than the word of God.

Now he’s beginning to sound like Professor Richard Dawkins. “Who was this guy?” you may be wondering.

Here’s one last hint. Abraham Lincoln once remarked that he never tired of reading him. (See A Literary History of the American People by Charles Angoff, New York, London, A.A. Knopf, 1931, p. 270.)

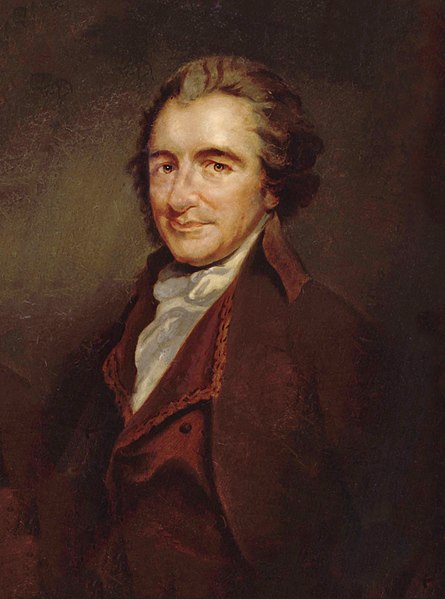

Give up? The author’s name is Thomas Paine (1737-1809), a leading figure of the American Revolution and the author of Common Sense. The last two quotes are taken from Paine’s best-selling work, The Age of Reason, while the long quote at the beginning of this post is taken from his essay, The Existence of God. Paine’s argument for God’s existence in this discourse is heavily influenced by the physics of his day, which entailed that the universe would eventually run down if left to its own devices, and a similar argument can be found in Isaac Newton’s letter to Richard Bentley of February 11, 1693. However, there is an additional argument for God’s existence in Paine’s discourse: namely, that the universe must be the work of a Creator because it operates according to mathematical principles, suggesting that it is the work of a Mind – or as Paine puts it, “all the principles of science are of divine origin.”

Paine’s essay, The Existence of God, was actually a discourse he gave at the Society of Theophilanthropists, Paris, and it was probably read at their first public meeting, on January 16, 1797. The Theophilanthropists (“Friends of God and Man”) were a Deistic sect, formed in France during the latter part of the French Revolution. An article in The Catholic Encyclopedia describes the origins of the Theophilanthropists:

The legal substitution of the Constitutional Church, the worship of reason, and the cult of the Supreme Being in place of the Catholic Religion had practically resulted in atheism and immorality. With a view to offsetting those results, some disciples of Rousseau and Robespierre resorted to a new religion, wherein Rousseau’s deism and Robespierre’s civic virtue (regne de la vertu) would be combined.

The Theophilanthropists shared two basic beliefs: they believed in God and in a hereafter. Thomas Paine believed as much, for he wrote: “I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life.”

Now at last we are in a position to appreciate the significance of Paine’s criticisms of the way in which the natural sciences are taught in the schools. He was speaking to a French audience, and the target of his criticisms would have been the secular science curriculum that was adopted in revolutionary France. Paine objected to this curriculum, on the grounds that teaching scientific principles without any mention of their Divine Author would dampen students’ intellectual curiosity and foster shallow thinking, which would inevitably lead to atheism:

The evil that has resulted from the error of the schools, in teaching natural philosophy as an accomplishment only, has been that of generating in the pupils a species of Atheism. Instead of looking through the works of creation to the Creator himself, they stop short, and employ the knowledge they acquire to create doubts of his existence…

It has been the error of the schools to teach astronomy, and all the other sciences, and subjects of natural philosophy, as accomplishments only; whereas they should be taught theologically, or with reference to the Being who is the author of them: for all the principles of science are of divine origin. (Emphases mine – VJT.)

So here we have Thomas Paine, a leading figure in the history of skeptical thought, a fierce critic of religion and a hero of leading atheist Christopher Hitchens, expressly advocating the idea of bringing God back into the French science curriculum!

On the other hand, we have Intelligent Design Theory, which, in the words of ID proponent and attorney Casey Luskin, “refrains from untestable, unscientific, or unconstitutional claims about God, or the ‘supernatural'”, and which limits itself to making the modest claim that “life bears the informational characteristics we commonly find in objects we know were designed.” Indeed, Intelligent Design advocates are not even proposing that this claim should be taught in schools. In a 2005 article entitled, It’s Constitutional But Not Smart to Teach Intelligent Design in Schools, Casey Luskin argues that “Schools should teach the flaws in Darwinian theory rather than plugging intelligent design.” A pretty mild proposal, one would think.

It is ironic, then, that Christopher Hitchens, in his book God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, calls intelligent design (ID) “tripe” and “a huge menacing lurch forward by the forces of barbarism”, despite the fact that the proposals by Intelligent Design movement with regard to the American science curriculum of the 21st century are in no way religious, whereas the proposals made by Hitchens’ hero, Tom Paine, in relation to the French science curriculum of the late 18th century, explicitly advocate bringing God back into the science classroom. Go figure.

I shall leave it to readers to decide whether Intelligent Design is a religious agenda in disguise, as its paranoid critics contend, or whether it is simply a legitimate and intellectually honest way of doing science in the 21st century.