“Prove it . . .” is a familiar challenge, one, often strengthened to “unless you prove it I can disregard what you claim.” However, ever since Epictetus, c. 100 AD, it has met its match:

DISCOURSES

CHAPTER XXVWhen someone in [Epictetus’] audience said, Convince me that logic is necessary, he answered: Do you wish me to demonstrate this to you?—Yes.—Well, then, must I use a demonstrative argument?—And when the questioner had agreed to that, Epictetus asked him. How, then, will you know if I impose upon you?—As the man had no answer to give, Epictetus said: Do you see how you yourself admit that all this instruction is necessary, if, without it, you cannot so much as know whether it is necessary or not? [Notice, inescapable, thus self evidently true and antecedent to the inferential reasoning that provides deductive proofs and frameworks, including axiomatic systems and propositional calculus etc. Cf J. C. Wright]

Lesson one, there are unproven antecedents of proof, including the first principles of right reason, here especially laws of logic. In this case, if one tries to prove, one is already using them and if one tries to object one cannot but use them, so we sensibly accept them as self-evident, pervasive first principles.

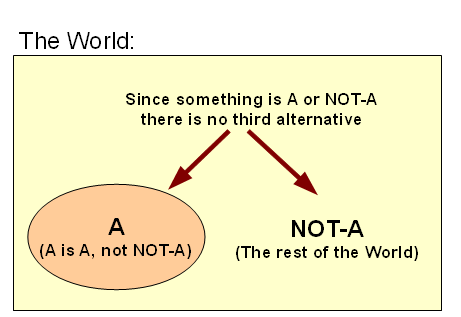

As there are always those who need it, pardon a diagram that abstracts from a bright red ball A on a table, to help us recognise the first cluster of such principles:

Okay, okay, here is my actual example of a ball on the table:

And, here is one in the sky, for good measure, Betelgeuse, as it dimmed in 2019 . . . identity with change:

In for a penny, in for a pound. Let me suggest a partial but useful list of such principles of logic and wider right reason . . . and yes, this chart marks a stage in my understanding of Cicero’s point:

This is already a big hint on our limitations in reasoning. We may now bring to bear in effect the Agrippa trilemma, to see how chains of proof and wider warrant confront us with a triple challenge, leading to having to — usually, implicitly — accept finitely remote first plausibles:

We are already duly humbled.

It gets “worse.”

For, “proof” itself is a slippery concept. The very model is of course Euclidean Geometry, with its complex system of theorems — derived from, uh, ah, um, first claims, i.e. axioms. Which, in this case, were subjected to a huge debate and now Mathematical systems are often viewed as logic-game worlds constructed from frameworks of axioms we find interesting and/or useful.

Then, came Godel, and SEP is helpful:

Gödel’s two incompleteness theorems are among the most important results in modern logic, and have deep implications for various issues. They concern the limits of provability in formal axiomatic theories. The first incompleteness theorem states that in any consistent formal system F within which a certain amount of arithmetic can be carried out, there are statements of the language of F which can neither be proved nor disproved in F. According to the second incompleteness theorem, such a formal system cannot prove that the system itself is consistent (assuming it is indeed consistent). These results have had a great impact on the philosophy of mathematics and logic . . .

Proof, in the sense, accessibility from some reasonable, finite cluster of axioms, for systems of reasonable complexity, is thus different from truth. Truth, accurate description of states of affairs. (And BTW, practical axiomatisations typically are built to be compatible with recognised facts, some of which may be self-evident like || + ||| –> |||||.)

Already, we are in trouble. It gets deeper once we come to Science. As in, follow the Science, Science has proved etc. Next to me is a gift [thanks Aunt X], “Proving Einstein right.” Only, science is incapable of such strong-sense proof. We may empirically support theories as explanations through empirical evidence, but at most we can say our theories are plausible and may prove — test out — to be at least partly true but are subject to the limits of inductive thinking. That is, we face the pessimistic induction, that our explanations that seemed ever so plausible have historically consistently been sharply limited or outright wrong often enough to give us pause.

We already saw a weaker sense of to prove, to test with some rigor. Bullet proof, means, tested and found credibly resistant to certain specified standard projectiles.

So, by extension scientific proofs can be reinterpreted to mean that science is a case of weak-sense knowledge: tested, warranted, credibly . . . or plausibly, or even possibly . . . true [so, reliable] belief.

It gets worse, welcome to . . . tada . . . RHETORICAL proof. Pisteis, as in:

Updated July 30, 2019

In classical rhetoric, pistis can mean proof, belief, or state of mind.

” Pisteis (in the sense of means of persuasion) are classified by Aristotle into two categories: artless proofs ( pisteis atechnoi), that is, those that are not provided by the speaker but are pre-existing, and artistic proofs ( pisteis entechnoi), that is, those that are created by the speaker.”

A Companion to Greek Rhetoric, 2010Etymology: From the Greek, “faith”

Yes, pisteis comes from pistis, for faith, confident (and hopefully well supported) trust. Which brings up Aristotle’s three main appeals of “artistic” proof, pathos, ethos, logos. Roughly, force of emotions, force of credibility [to bring trust], force of facts and logic. Our emotions have a cognitive aspect and so we can asses the quality of judgements and expectations. Authorities, experts or even witnesses carry credibility to varying degrees but are no better than underlying facts, assumptions, reasoning. So, in the end it is to facts logic and associated assumptions that we must go. And, lo, behold, the result: reasonable, responsible faith.

Our humbling is now complete. We cannot but live by faith, the issue is, which faith, why. Where, hyperskepticism is now exposed as smuggling a certain unquestioned faith in the back door.

This brings us full circle to common sense principles, that we should heed Locke: roughly, we should accept that it is better to walk by the limited and perhaps flickering candle-light we have, than to demand full light of day and snuff out the candle, leaving us in the dark.

Coming back to a recent diagram, here we are, as credibly embodied, error prone but knowing creatures sharing a common world:

Reason, warrant and truth are not fully captured in the net we call proof. Where, too, proof itself is not as firm as we may naively imagine. Let us therefore seek prudence. END