From ScienceDaily:

How do the large-scale patterns we observe in evolution arise? A new paper in the journal Evolution by researchers at Uppsala University and University of Leeds argues that many of them are a type of statistical artefact caused by our unavoidably recent viewpoint looking back into the past. As a result, it might not be possible to draw any conclusions about what caused the enormous changes in diversity we see through time.

The diversity of life through time shows some striking patterns. For example, the animals appear in the fossil record about 550 million years ago, in an enormous burst of diversification called the “Cambrian Explosion.” Many groups of organisms appear to originate like this, but later on in their evolutionary history, their rates of diversification and morphological change seem to slow down. These sorts of patterns can be seen both in the fossil record, and also in reconstructions of past diversity by looking at the relationships between living organisms, and they have given rise to a great deal of debate.

Do organisms have more evolutionary flexibility when they first evolve? Or do ecosystems get “filled up” as more species evolve, giving fewer opportunities for further diversification later on? In their new paper, Graham Budd and Richard Mann make the provocative argument that these patterns may be largely illusory, and that we would still expect to see them even if rates of evolutionary change stay the same on average through time.

…

As a result, the patterns we discover by analyzing such groups are not general features of evolution as a whole, but rather represent a remarkable bias that emerges by only studying groups we already know were successful. This bias, called “the push of the past,” has indeed been known about theoretically for about 25 years, but it has been almost completely ignored, probably because it was assumed to be negligible in size. However, Budd and Mann show that the effect is very large, and can in fact account for much of the variation we see in past diversity, especially when we combine it with the effects of the great “mass extinctions” such as the one that killed off the dinosaurs some 66 million years ago. Because the resulting patterns are an inevitable feature of the sorts of groups available for us to study, Budd and Mann argue, it follows that we cannot perceive any particular cause of them: they simply arise from statistical fluctuation.

The push of the past is an example of a much more general type of pattern called “survivorship bias” which can be seen in many other areas of life, for example in business start-ups and finance and the study of history. In all these cases, failure to recognize the bias can lead to highly misleading conclusions. Budd and Mann argue that the history of life itself is not immune to such effects, and that many traditional explanations for why diversity changes through time may need to be reconsidered — a viewpoint that is bound to prove controversial. Paper. (paywall) – Graham E. Budd, Richard P. Mann. History is written by the victors: The effect of the push of the past on the fossil record. Evolution, 2018; DOI: 10.1111/evo.13593 More.

Yes, histories are written by the victors. In media, the better practitioners often understand this type of thing. There are other sources of bias as well. For example, they say “it takes three to make a trend.” That does not mean that just because you have found three valid instances of the same event in succession, you have a trend. It just means you definitely don’t have a trend if you don’t have three. Even if you have three, you may never find a fourth.

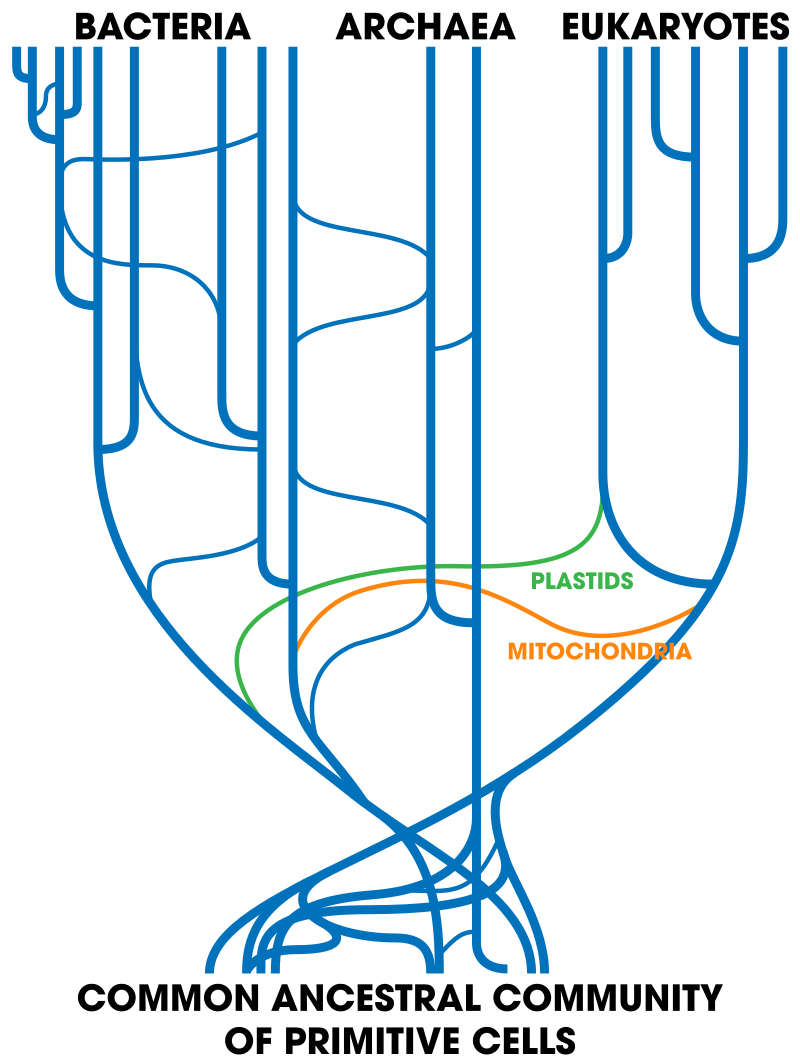

But it feels kind of weird hearing statements about patterns like that in science. So much — Darwin’s finches, the Tree of Life, the Biological Species Concept, junk DNA — depend on the need to see a pattern that confirms what the evolutionary theorists believe more than a need to see what is there.

We are standing in an ever-rolling stream of history that is full of facts whose relationship to each other is somewhat, though not entirely, fluid. Accepting that will certainly change emphases in science. For example, human are much closer, in the scheme of things, to naked mole rats than to octopuses. But what can we deduce from that fact? A thesis about human relationships based on naked mole rats is just as likely to be bunk as a similar thesis based on octopuses would be. Because the pattern can’t be pushed as far as that without degenerating into nonsense or worse.

See also: A physicist looks at biology’s problem of “speciation” in humans