We’ll probably never know what dinos were really like inthe sense that we can know what horses are like but we learn from Will Tattersdill at H-Sci-Med-Tech about the different ways we have understood them. Reviewing Dinosaurs Ever Evolving: The Changing Face of Prehistoric Animals in Popular Culture by Allen A. Debus, (1926–2009), he writes

We’ll probably never know what dinos were really like inthe sense that we can know what horses are like but we learn from Will Tattersdill at H-Sci-Med-Tech about the different ways we have understood them. Reviewing Dinosaurs Ever Evolving: The Changing Face of Prehistoric Animals in Popular Culture by Allen A. Debus, (1926–2009), he writes

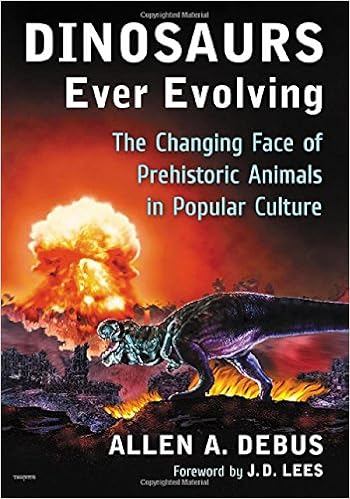

If you are interested in the history of dinosaurs in popular culture, Debus is an author you simply cannot ignore. He has written copiously on the “imaginative impact” of dinosaurs, and he is clearly on to something when he proposes to offer “an alternate history” of their evolution (pp. 265, 3)—a history written not across the geological ages of the Mesozoic (Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous) but rather across the far thinner strata of time in which humanity has reassembled and named them. Dinosaurs were conceived of very differently a century ago than they are today, not just by scientists but by writers, artists, and filmmakers as well, and Debus’s acknowledgment of this difference, and of its ability to inform us about ourselves, is a central virtue of his book. I find myself less convinced by the specific, tripartite breakdown of history that it adopts; despite the disclaimer that “the three ages of the dinosaur as outlined here aren’t temporally exclusive” (pp. 8–9), the partitions between “didactic,” “doomsday,” and “humanoid” dinosaurs feel a little too clean and orderly (the latter two, in particular, share an unhelpfully large grey area in my estimation). My copy of the book contains an apparent misprint, which gives it the alternative title Three Ages of the Dinosaur. It is a logical working title for Debus’s manuscript, but the final one is far better: dinosaurs are indeed “ever evolving” in the public sphere, and the perpetual shifts in the way we tell stories about them ultimately frustrate any neat division into “eras,” however carefully considered.

In pointing out that the human reception of dinosaurs is in some respects as worthy of study as dinosaurs themselves, Debus does a huge service to those who work in the history of science; his service to literary critics is to be found in the inclusive breadth of his source material, which unpretentiously includes everything from Jules Verne to Toho film productions. Few indeed will be the readers who do not find out about some previously unheard of dino-text in this work. Toward the beginning, Debus differentiates himself from W. J. T. Mitchell’s pathfinding study The Last Dinosaur Book (1998) by expanding his range “beyond (strictly) the visual arts” (p. 5), and the easy familiarity with which he moves between print material as disparate as Henry Knipe’s Nebula to Man (an epic poem about evolutionary history published in 1905) and John C. McLoughlin’s Toolmaker Koan (a 1988 science fiction novel in which humanoid dinosaurs prompt the great extinction event) is enviable. More.

See also: Study: Two years’ darkness provides clue to total dinosaur extinction