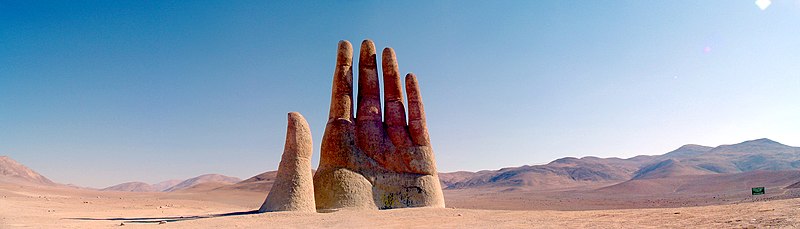

Further to “What are the odds that this is the result of wind erosion?: Some will say, it must be the product of human intelligence, because it is a human hand. But wait. We assume it is a product of human intelligence because humans are the only entities that occur naturally in our world who would be able to create this work of art (it has no apparent functional value but it does have obvious meaning).

But we actually mean that at least a human level of intelligence is required to create such an object. The fact that it is a human hand should not put us off the track here. Were the sculpture a chimpanzee hand, we would not infer that a chimpanzee created it. An intelligent alien could have created a sculpture of a human hand. We dismiss that possibility due to our lack of evidence for the alien’s existence; not due to his supposed lack of ability or interest.

So what we know from the object itself, and not from our background information about the inhabitants of our planet, is that the sculpture was created by an intelligent being who wished to impact other intelligent beings in an intellectual or aesthetic way. Not, apparenbtly, to convey specific information, like directions. To have such a goal, as his personal goal, implies consciousness.

Now recall some of Yale computer science prof David Gelernter’s comments on conciousness in “The Closing of the Scientific Mind”:

What is consciousness for? What does it accomplish? Put a real human and the organic zombie side by side. [cf Zombie Fred] Ask them any questions you like. Follow them over the course of a day or a year. Nothing reveals which one is conscious. (They both claim to be.) Both seem like ordinary humans.

So why should we humans be equipped with consciousness? Darwinian theory explains that nature selects the best creatures on wholly practical grounds, based on survivable design and behavior. If zombies and humans behave the same way all the time, one group would be just as able to survive as the other. So why would nature have taken the trouble to invent an elaborate thing like consciousness, when it could have got off without it just as well?

Such questions have led the Australian philosopher of mind David Chalmers to argue that consciousness doesn’t “follow logically” from the design of the universe as we know it scientifically. Nothing stops us from imagining a universe exactly like ours in every respect

except that consciousness does not exist. Nagel believes that “our mental lives, including our subjective experiences” are “strongly connected with and probably strictly dependent

on physical events in our brains.”

But—and this is the key to understanding why his book posed such a danger to the conventional wisdom in his field—Nagel also believes that explaining subjectivity and our conscious mental lives will take nothing less than a new scientific revolution. Ultimately, “conscious subjects and their mental lives” are “not describable by the physical sciences.” He awaits “major scientific advances,” “the creation of new concepts” before we can understand how consciousness works. Physics and biology as we understand them today don’t seem to have the answers. On consciousness and subjectivity, science still has elementary work to do. That work will be done correctly only if researchers understand what subjectivity is, and why it shares the cosmos with objective reality.

Read it again. If I understand correctly, those are fighting words.

We must take seriously that subjectivity and consciousness are not part of the materialist (and Darwinist) paradigm, and therefore what is needed is not a way to shoehorn them in but a new paradigm.

Yes.

Gelernter will probably take some heat for pinpointing Darwinism as a major source of the “sciencey” clutter that keeps us from facing this issue squarely. Next time I empty the Inbox, there’ll like as not be a release announcing that “Chimps can reason like humans, study shows.” And all the science writers who read it undergo a moment of confusion in which they fail to ask, well, why are chimps still panhooting in the trees, throwing rotten bananas then? If all this is true, it’s momentous. It means, for one thing, that many millions of years of reasoning powers can make absolutely no difference to a life form. And then something isn’t adding up.

But at bottom, we all know it isn’t really true. It’s just something we need to think in order to avoid facing the issues Gelernter isn’t afraid to face.

He had better stand his ground. Many a thinker has fallen by the wayside, whimpering weakly that he would never mean to offend Darwin’s trolls and he promises to go away and be a good boy now. That, of course, is the last anyone ever hears from him. Like the man said, cheaper than a frontal lobotomy.

Stand yer ground, prof!