Canadian weekly Maclean’s recently featured an article by Brian Bethune titled, Did Jesus really exist? The article, which drew upon a book recently published by New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman, titled, Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior, argues that the Gospel accounts of Jesus are largely based on unreliable memories and a highly distorted oral tradition. But Bethune does not stop there: citing the work of New Atheist Richard Carrier, he goes beyond Ehrman and maintains that Jesus may never have even existed at all.

The issues raised by Professor Ehrman in his book are of immense philosophical significance, for they pertain to the trustworthiness of human testimony. If Ehrman is correct, then no account of a supernatural or paranormal occurrence can ever be trusted, no matter how large the number of witnesses, because human memory is too unreliable.

A. Executive Summary

This post is not intended to be a review of Professor Ehrman’s latest book, but a wide-ranging discussion of some of the key points he raises, which are helpfully summarized by Brian Bethune in his article. In a nutshell, Ehrman claims that oral traditions passed on within a community are liable to distortion, for two reasons: those who are charged with passing on the traditions have a tendency to continually reinterpret those traditions, in the light of changing circumstances; and as anyone who has played the game of “telephone” (or Chinese whispers) knows, people who hear a story third-hand, fourth-hand, or even tenth-hand, will invariably receive only a garbled version of the original. As Ehrman puts it, “When it comes to Jesus, all we have are memories… Memories written after the fact. Long after the fact. Memories written by people who were not actually there to observe him… They are memories of later authors who had heard about Jesus from others, who were telling what they had heard from others, who were telling what they had heard from yet others. They are memories of memories of memories.” What this means, argues Ehrman, is that we have no reliable way of knowing what Jesus said and did: although Ehrman insists that he was an historical figure, he is, to a large extent, an invention of the Christian community.

In addition, Ehrman contends that an individual’s memory is highly malleable and liable to change over the course of time, especially when the event being recalled is an extraordinary one (e.g. a supernatural or paranormal occurrence). Group memory of an event witnessed by many people is even less reliable, as an individual’s memory of the event can be easily modified by listening to the recollections of the dominant member of the group. Thus even if we could interview the people who were eyewitnesses to Jesus’ extraordinary deeds, the information that we’d obtain from them would be highly unreliable.

The upshot of the arguments put forward by Professor Ehrman (and reported by Bethune in his article) is that we know very little about the historical Jesus. The only solid facts Ehrman thinks we can know about Jesus are that he was an apocalyptic Jewish preacher, baptized by John, who taught in parables and was regarded as a healer, and who caused a disturbance in the Temple that led to his arrest, his trial under Pontius Pilate and his execution on charges of sedition. Bethune thinks even these facts are doubtful, and he reproaches Ehrman for not being skeptical enough about Jesus: what we should say, if we are honest, is that we know nothing about him at all.

What I’ll be arguing in this post is that while Ehrman has done a lot of reading on the ways in which our memories can deceive us, he is unfamiliar with the literature showing how well our memories can preserve our recollections of events, when we want them to. I will show that in communities where information is transmitted orally, a high value is placed on accuracy, and that while events being recalled may be reinterpreted to address the community’s current situation, they are not fabricated out of thin air. In addition, Ehrman appears to be completely unaware of the burgeoning literature on archival memory, whereby an individual who witnesses a highly significant event makes a decision to commit it to memory: “I shall never forget this as long as I live.” Once that decision is made, the events committed to memory are in effect set in stone: they remain unaltered over a period of decades. Had the original eyewitnesses to Jesus’ life made the decision to commit His words and deeds to memory in such a fashion, we would expect them to have a very solid recollection of what they committed to memory. What’s more, we can be fairly sure that no dominant individual, within the group of Jesus’ disciples, could have distorted the memories of the group, precisely because the Gospels are so unsparingly honest about the faults and foibles of prominent figures such as Peter, James and John: they record a number of incidents which cast these figures in a bad light.

Finally, it needs to be borne in mind that while some of the Gospel stories of Jesus’s sayings and deeds appear to be inauthentic, they are peripheral. Most of the accounts about Jesus in the Gospels are internally consistent, mutually reinforcing, and externally well-corroborated, making them worthy of credence.

A short note on Biblical inerrancy versus Biblical reliability

The question of whether the Gospels contain occasional errors of fact (as many scholars would maintain) is quite separate from the question of whether they can be trusted overall as a source of reliable information. An affirmative answer to the first question does not entail a negative answer to the second.

Unfortunately, Bart Ehrman sometimes confuses these two questions: in his book, he attempts to undermine the reliability of the Gospels by endeavoring to show that they contain errors. Thus at one point, Ehrman highlights certain contradictions in the Gospel accounts, while taking a gratuitous swipe at Christian apologists who endeavor to harmonize them. In his article for Maclean’s, Bethune recounts one story related by Ehrman, on how Christian apologists attempted to explain away conflicting Gospel accounts of the raising of Jairus’ daughter from the dead, when he was a young man:

Ehrman recalls how, as a young professor, he asked an older expert — a proponent of sturdy oral transmission — how he dealt with the fact the gospels give two accounts of Jesus’s visit to the 12-year-old daughter of Jairus: one in which the girl is dying, another in which she is already dead. The answer, that there must have been two visits to the (unlucky) child, was essentially impossible for anyone not committed to gospel truth.

Let us assume for argument’s sake that some of the Gospel accounts are mutually contradictory and/or factually mistaken. What does that prove? All it establishes is that the Bible is not inerrant. However, the question we have to address is whether the Gospels, taken as a whole, are historically reliable. For instance, the writings of the Roman historian Tacitus contain some factual errors, such as his confusion of the two daughters of Mark Antony and Octavia Minor, who are both called Antonia; however, that in no way impugns their overall reliability.

I should add that the “expert” who advised Ehrman was poorly informed. Dr. Lydia McGrew specifically addresses the raising of Jairus’ daughter in a recent blog essay, in which she puts forward two highly plausible suggestions. The first is that “even if St. Matthew was an eyewitness to the miracle, he need not be claiming to remember verbatim how Jairus worded his request” to Jesus, to come and heal his daughter. He may therefore have omitted certain details from his narrative, for the purpose of economy – such as the later arrival of Jairus’ servants.

The second possibility, suggested to Dr. McGrew by her husband, Professor Tim McGrew, is as follows:

Jairus is distraught, he knows that even coming to Jesus has taken some time and that the child was dying when he left, and he says something to Jesus like, “My daughter is on the point of death. By this time, I’m sure she is dead! But come and lay your hand on her and she will live.” One gospel reports “on the point of death” and the other reports “is dead.” This is an economical and not at all implausible harmonization.

I should point out in passing that although the McGrews are stalwart defenders of the reliability of the Gospels, they are in no way committed to a belief in Biblical inerrancy.

B. How reliable is oral transmission of information within a community, and how reliable was it within the early Christian community?

Is oral transmission reliable, within a culture?

In his article, Bethune reports on Ehrman’s discovery that stories often grow in the telling, when transmitted orally:

“For the past two years I’ve been reading what I can about memory,” says Ehrman in an interview, “and learning that what we were taught in grad school— what’s still taught in grad school — is untrue.” Changes in oral memory, psychologists, sociologists and anthropologists have found, are actually more radical than in literary transmission, because the literary tends to fix, unchanged, the received text. But every act of oral transmission, Ehrman cites one memory expert as declaring, “is also an act of creation.”

Ehrman does have a legitimate point here: oral transmission is not static, and traditions within a community can (and do) evolve over the course of time. However, evolution is not revolution, and the available evidence does not support Ehrman’s claim that traditions change radically. What’s more, there is strong evidence that local communities place a high value on accuracy of transmission.

|

Masked Dancers at a Canadian potlatch, from Edward S. Curtis’ North American Indian Portfolio, 1915. Courtesy of Northwestern University Library, Digital Library Collections. Stories are frequently told by native Canadians at potlatch ceremonies. The storytellers place a high value on accuracy of transmission in their narration, although traditions may sometimes be reinterpreted in the light of current events.

In a carefully balanced online essay, titled, Oral Traditions, University of British Columbia scholar Eric Hanson highlights both the accuracy of oral transmission and its ability to evolve over time, in order to suit the needs of the community:

Oral-based knowledge systems are predominant among First Nations. Stories are frequently told as evening family entertainment to pass along local or family knowledge. Stories are also told more formally, in ceremonies such as potlatches, to validate a person’s or family’s authority, responsibilities, or prestige.

…Such stories often teach important lessons about a given society’s culture, the land, and the ways in which members are expected to interact with each other and their environment. The passing on of these stories from generation to generation keeps the social order intact. As such, oral histories must be told carefully and accurately, often by a designated person who is recognized as holding this knowledge. This person is responsible for keeping the knowledge and eventually passing it on in order to preserve the historical record.

Notwithstanding the importance placed on accuracy, oral narratives often present variations — subtle or otherwise — each time they are told. Narrators may adjust a story to place it in context, to emphasize particular aspects of the story or to present a lesson in a new light, among other reasons. Through multiple tellings, a story is fleshed out, creating a broader, more comprehensive narrative. Should listeners ever recount the narrative elsewhere, they would likely alter it to some degree to reflect their understandings of events and to better apply the story to its present context. In some instances, precision may be crucial: both precision and contextualizing have their place in oral societies…

In 2002, the Tsilhqot’in took the province of British Columbia to court to assert title to their lands. Justice David Vickers found that the oral histories presented to him by members of the Tsilhqot’in Nation were sufficient to prove their Aboriginal title. He also rejected the Crown’s claims that oral tradition was unreliable or should be measured against written documents, as it was equally impossible to determine the accuracy of historic fieldnotes or, more specifically in the Tsilhqot’in case, a 1900 ethnography on the “Chilcotin Indians.” More broadly, Vickers observed that “disrespect for Aboriginal people is a consistent theme in the historical documents.”

Delgamuukw and subsequent court cases have forced Western legal systems to reconsider the validity of Aboriginal oral traditions and their continued significance and relevance in Aboriginal societies and cultures.

How is this relevant to the reliability of the New Testament? What it tells us is that: (a) the early Christian community was quite capable of preserving historical memories of Jesus’ deeds and teachings, during the 40-odd years between His death and St. Mark’s composition of the first written Gospel, if it wished to do so; (b) at the same time, the words ascribed to Jesus in these oral traditions may reflect the current thinking of the Christian community.

One example of this kind of development can be found in Mark 7:19, where the teaching of Jesus in verse 15 (“Nothing outside a person can defile them by going into them. Rather, it is what comes out of a person that defiles them”) is given a contemporary twist: “In saying this, Jesus declared all foods clean.” Had the meaning of Jesus’ teaching been understood in this way from the very beginning, there would never have been any argument within the early Church as to whether pagan converts were still bound by Jewish dietary laws of the Old Testament – and yet we know for a fact that it required nothing less than a council of the whole church (held in A.D. 49) to resolve this simmering controversy within the early Christian community. However, St. Mark’s contemporary gloss on the words of Jesus does not detract from the authenticity of the words themselves.

How reliable is oral transmission, over the long-term?

|

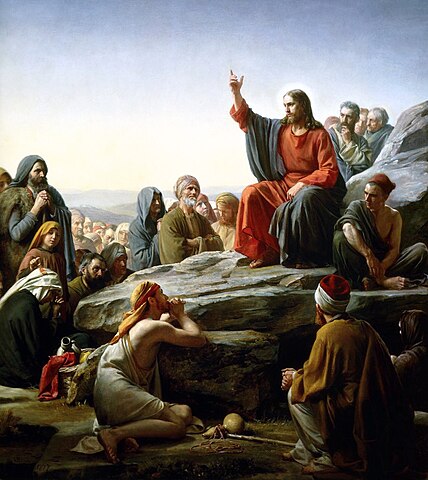

Carl Heinrich Bloch. The Sermon on the Mount. 1877. Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In his article in Maclean’s, Brian Bethune attempts to marshal further support for his case, by citing studies which allegedly undermine the reliability of long-term memory within a community:

Memory studies and experiments cited by Ehrman show it would have been impossible to control the contents of stories about Jesus. One experiment a decade ago took 33 university students to a morgue, the sort of experience they would be bound to talk about. Follow-up by the researchers showed that within three days news of the visit had spread in garbled form, via intermediaries, to 881 people. The more often a story is repeated — and a growing new religious community will repeat its stories very often – the more it changes. Repeat one 10 times, as in a game of telephone, and the most salient details — who exactly said what or did what to whom — will change the most. What are the chances, 50 years after the fact, that the author of the Gospel of Matthew remembered hearing the Sermon on the Mount — a polished and nuanced discourse — exactly as it was said?

Three points need to be kept in mind here. In the first place, the experiment described by Bethune (Harber K. D., Cohen D. J. (2005). “The emotional broadcaster theory of social sharing“, Journal of Language and Social Psychology 24, 382–400) made no attempt to measure the accuracy of the accounts of the students’ visit to the morgue; consequently, it cannot be validly adduced as evidence against the reliability of human memory over time. Rather, the aim of the study was to test a novel theory called the Emotional Broadcaster Theory (EBT) of emotional disclosure, which proposes that “the intrapsychic need to share experiences with others serves the interpersonal function of transmitting news.”

In the second place, Bethune’s argument that the more often a story is repeated, the more it changes, makes sense only if we assume (a) that the story is transmitted in a single direction, as in the telephone game, and (b) that there is no-one within the community whose job it is to monitor the accuracy with which stories are transmitted. But as we saw above, tribal communities have their own guardians of oral tradition, who place a high premium on accuracy. The idea that people would learn about this tradition on a “tenth-hand” basis (as Bethune supposes) is absurd; normally, they would learn it first-hand, from the designated story-teller within the community.

Finally, Bethune has chosen a very poor example in referring to Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. For it just so happens that we have two different versions of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount: the long version found in St. Matthew’s Gospel (chapters 5 to 7) and the abbreviated version in St. Luke’s Gospel (6:17-49), which is sometimes called the Sermon on the Plain. (See here for a comparison of the two versions and here for a discussion of how they may have arisen.) Nobody is suggesting that St. Matthew’s account of the Sermon on the Mount reflects the ipsissima verba of Jesus, or that what Jesus said was necessarily uttered on a single occasion: it may well represent a conflation of what was said on several occasions. But the real question we need to address is: did Jesus actually say what He is supposed to have said?

To answer that question, let us bear in mind that even if Jesus preached for only one hour a day, over a three-year-period, He would have uttered about ten million words (150 words/minute x 60 minutes x 1,095 days). However, the entire New Testament records a mere 36,450 words uttered by Jesus Himself, or less than 0.3% of what Jesus actually said. What we have in the Gospels, then, is a selection from the sayings of Jesus. Which leads us to ask: how was the selection made? It is reasonable to surmise that the sayings of Jesus were carefully “winnowed” by the Christian community after His death and resurrection, and that only the most well-attested utterances were deemed worthy of inclusion in the church’s collection of Jesus’ sayings. Once selected, these utterances could have easily been carefully committed to memory by members of the early Christian community.

The Argument from Undesigned Coincidences: the McGrews’ argument for the overall reliability of the New Testament

Philosophy professor Timothy McGrew (of Western Michigan University) and his wife, Dr. Lydia McGrew, have revived an argument for the reliability of the New Testament, based on what they call undesigned coincidences. (The argument was originally put forward by nineteenth century Christian apologists William Paley D.D., in his work, Horae Paulinae (London, 1840) and by John James Blunt (1794-1855) in his work, Undesigned Coincidences in the Writings of both the Old and New Testament (New York, 1847).)

“What’s an undesigned coincidence?” I hear you ask. The following brief excerpt, which explains the concept, is taken from slides 9 and 10 of a presentation given by Dr. Timothy McGrew (Professor and Philosophy Department Chair, Western Michigan University), titled, Internal Evidence for the Truth of the Gospels and Acts, at St. Michael Lutheran Church, on February 27, 2012:

Sometimes two works by different authors interlock in a way that would be very unlikely if one of them were copied from the other or both were copied from a common source.

For example, one book may mention in passing a detail that answers some question raised by the other. The two records fit together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

Fictions and forgeries aren’t like this.

1. Why leave loose ends or raise questions that you do not have to?

2. How can you control what other people will write to make it interlock with what you have written?

But we would expect to find such interlocking in authentic, detailed records of the same real events told by different people who knew what they were talking about.

In his presentation, Professor McGrew discusses the miracle of the feeding of the 5,000, which is the only miracle of Jesus to be narrated in all four Gospels. He begins with Mark’s narrative, in which Jesus invites his apostles to come with him to a quiet place and get some rest, because there were “so many people were coming and going that they did not even have a chance to eat” (Mark 6:31). Later in the narrative, when distributing the loaves and fishes, Jesus orders his disciples to have the people sit down in groups “on the green grass” (Mark 6:39). Commenting on the narrative, Professor McGrew declares:

In reading this passage, two questions come to mind:

1. Why were so many people “coming and going”? What was causing all the crowds?

2. What’s this business about “green grass” in the Holy Land? Isn’t the area a desert?Mark doesn’t provide the answers, but interlocking data in John’s gospel does.

It turns out that John’s account of the feeding of the 5,000 resolves both of these difficulties:

John tells us that the Passover Festival was near. Well, it appears that this little nugget of information clears up both questions:

1. The crowds were so large because of the annual Passover festival, which drew more than 2.5 million pilgrims to Jerusalem each year, according to Josephus. Likely, that number is exaggerated, but it does make a point. There were a lot of people headed for Jerusalem, and the roads would have been thronged with travelers.

2. Passover occurs during the growing season in that part of the world, which explains the green grass.

In this case, John explains Mark. It’s one more undesigned coincidence that demonstrates the interlocking nature of the gospels. It further supports the ideas that these are independent accounts, and strengthens the case for historical accuracy

Professor McGrew lists no less than a dozen undesigned coincidences in his presentation. These coincidences cover incidents ranging from Herod the tetrarch’s comments abut Jesus to Jesus’ saying about destroying and rebuilding the Temple.

More recently, Dr. Lydia McGrew gave an excellent talk on Undesigned Coincidences in the Gospels and Acts, on March 29, 2016, which I commend to readers:

In her talk, Dr. McGrew specifically addresses an argument that is often put forward by skeptics in an attempt to “explain away” the undesigned coincidences found in the Gospels: Markan priority, it is alleged, can account for these differences. Not so, argues Dr. McGrew. What we actually find is that these “undesigned coincidences” are most numerous, not in St. Mark’s Gospel (which was written first), but in St. John’s Gospel (which was written last).

Dr. McGrew handily disposes of the skeptical suggestion that the dove-tailings between the different Gospel accounts may have been intentionally designed: in practice, it would be extraordinarily difficult to design two or more accounts that would do that, especially when these stories were written over an interval of a few decades.

For those who are interested, an excellent resource page on undesigned coincidences can be found here. Professor Tim McGrew’s six-part series on undesigned coincidences can be found here, and his reply to agnostic critic Ed Babinski can be found here.

The upshot of all this is that even if we were to allow the possibility of the Christian tradition regarding Jesus’ life and teachings being heavily corrupted during the first few decades of Christianity, the internal evidence of the Gospels themselves strongly indicates that in fact, this tradition wasn’t corrupted, but rather, that it was preserved with a high degree of accuracy. Were this not the case, then Gospel accounts of the same incident would not dovetail one another, as Mark’s and John’s accounts of the Feeding of the 5,000 do.

I should add that there is impressive external evidence for the reliability of the New Testament, summarized by Professor Tim McGrew in another presentation given in 2012. He points out that Colin Hemer, in his work, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History (Tübingen: Mohr, 1989), pp. 108‐58, goes through the last 16 chapters of Acts almost verse‐by‐verse: “Hemer lists 84 specific facts from those 16 chapters that have been confirmed by historical and archaeological research—ports, boundaries, landmarks, slang terminology, local languages, local deities, local industries, and proper titles for numerous regional and local officials.”

C. How reliable is an individual’s oral memory, over the long-term?

Experimental evidence for the reliability of long-term memory and oral history

|

Fourth battle of Montecassino (Operation Diadem): Sketchmap of Allied plan of attack in Italy, May 1944. Professor Howard S. Hoffman’s recollections of fighting in the fourth and final Battle of Montecassino in May 1944 formed the subject of a fascinating study of long-term memory, conducted by his wife, Dr. Alice Hoffman, an acknowledged expert on oral history. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

As we have seen, Professor Bart Ehrman contends that an individual’s long-term memory is highly unreliable, and that oral histories based on people’s recollections of past events cannot be trusted. If he had researched the subject of oral history more carefully, Ehrman might have come to a very different conclusion.

Powerful experimental evidence for the reliability of long-term memory and oral history is provided in a study by Alice M. Hoffman and Howard S. Hoffman, titled, Reliability and Validity in Oral History: The Case for memory in Memory and History: Essays on Recalling and Interpreting Experience, ed. Jaclyn Jeffrey and Glenace Edwall, 107-130 (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1994). Alice M. Hoffman, a former Assistant to the Deputy Secretary for Labor and Industry for the State of Pennsylvania, is renowned as a specialist in oral history who has become known as an “oral historian’s oral historian.” She is past president of the Oral History Association and has been an influential force in the development of oral history in the United States. In her paper, she describes a fascinating project, where she tested the reliability of her husband Howard’s memory of World War II over a period of decades, and then subsequently checked their accuracy by comparing them with detailed official reports of the events her husband described. Her research findings indicated that humans possess a kind of memory which could be called archival memory: once they make a firm decision to commit an important event to memory for the rest of their lives, the events committed to memory are crystallized, and it becomes virtually impossible to alter their recollections.

Summarizing her findings, Dr. Hoffman wrote:

While the memories presented here are primarily derived from just one individual, they indicate that within the range of human memory it is possible to reliably and accurately recover past events and to amplify and extend the existing written record. Howard’s memories, however, are not accurate with respect to exact dates or to whether “the water was warm or cold.” In this respect Cornelius Ryan [a scholar who is skeptical of “oral history” – VJT] is probably right. Our findings suggest that if it is details of this sort that are needed, oral history and oral interviews are probably not the best source. Howard only remembers the weather in connection with the bitter cold during the Bulge, but nowhere else does he mention it.

One element we found in these memories is that they are so stable, they are reliable to the point of being set in concrete. They cannot be disturbed or dislodged. It was virtually impossible to change, to enhance, or to stimulate new memories by any method that we could devise. We think, therefore, that we have a subset of memory, here called autobiographical memory, which is so permanent and so largely immutable that it is best described as archival…

Archival memory, as we conceptualize it, consists of recollections that are rehearsed, readily available for recall, and selected for preservation over the lifetime of an individual. They are memories which have been selected much as one makes a scrapbook of photographs, pasting in some and discarding others. They are memories which define the self and constitute the persona which one retains, the sense of identity over time…

It appears that the impressions which are stored in archival memory are assessed at the time they occur, or shortly thereafter, as salient and hence important to remember. For this reason they are likely to be rehearsed or otherwise consolidated and become a part of archival memory... We think that if for one reason or another an event is deemed sufficiently salient to a person’s life, it will be rehearsed either internally or in conversation. It is commonplace in the language we use with these stories that, when they are rehearsed out loud, they are often concluded with the words, “I shall never forget it as long as I live.” Our experiment verifies such a statement, if not for “as long as I live,” then at least for forty years or more. We think that if this rehearsal fails to occur, however, the event will be unavailable by any ordinary means devised to bring it to the fore. (pp. 124-125)

Howard S. Hoffman is an experimental psychologist and professor at Bryn Mawr College who has specialized in the scientific analysis of behavior, and in particular the mechanisms of learning and retention. Commenting on his wife’s research findings on oral memory, Professor Hoffman wrote:

When Alice and I started this project I had mixed feelings. As a scientist I was interested in learning something about the nature of long-term, autobiographical memory. As the subject, however, though I was curious about the possible results, I was also apprehensive. I knew I was going to dig into my memory claim on two widely separated occasions. I wondered if I would be consistent; that is, reliable in my recall. Would the stories change in their retelling, and if so how? Would there be a false progression toward making myself something of a hero? It also seemed possible that I might exhibit a loss of memories in the interval between recalls… Would this be the fate of my memories? I was also concerned as to how I might react when I would eventually read the daily log from Company C, Third Chemical Mortar Battalion — my company. I had a dread of that log, that it might reveal some horrible event in which I had participated or witnessed but which I was unable to recall. I was also concerned that I might discover that I had fabricated or plagiarized some of what I believed to be my memories. I did not think this was likely, but I realized that the daily log might very well contain evidence pointing to this possibility. As near as we could tell, none of these nasty things happened. My memory claims turned out to be quite reliable.

Though not word-for-word identical, the stories I told during the second interview were very nearly the same as the ones I told during the first interview. What is equally important, there was not a story in the first document that was not also in the second document…

Elizabeth Loftus has shown us that eyewitness accounts are subject to considerable distortion by factors that occur after the events they describe. Alice has alluded to several examples of such distortions in my memory claims… What seems surprising to me about these distortions is not that they occurred, but that there were so few of them...

More than twenty years ago, Alice’s observations doing oral histories led me to hypothesize that certain memories can be so resistant to deterioration with time that they are best described as archival. I think that our study provides considerable support for this proposition. (pp. 127-128)

How does this evidence bear on the reliability of the New Testament? In his article for Maclean’s, Brian Bethune draws his readers’ attention to a four-decade gap between the events recorded in Jesus’ life and St. Mark’s writing of the first Gospel, and he cites Professor Bart Ehrman’s argument that after such a long interval of time, an individual’s memories simply cannot be trusted. But as the long-term memory study conducted by the Hoffmans demonstrates, an individual’s memories can be preserved over a period of a few decades, with almost perfect accuracy. Ehrman’s case against the reliability of the Gospels crumbles.

How reliable is eyewitness testimony about a spectacular occurrence?

|

Jesus walks on water, by Ivan Aivazovsky (1888). Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In his article in Maclean’s, Bethune then proceeds to argue that eyewitness testimony is fundamentally unreliable:

As for eyewitness corroboration, far from controlling accuracy, eyewitnesses tend to offer the least trustworthy accounts, particularly when recalling something spectacular or fast-moving, like Jesus walking on water… And there’s no reason to believe memories of the more mundane details of Jesus’s life would be any more reliable.

First, the assertion that “eyewitnesses tend to offer the least trustworthy accounts” makes no sense. Think about it. What kind of account could possibly be more reliable than one given by people who actually witnessed the event in question? An account given by people who didn’t witness it? Now that’s an account I’d trust! (Not!)

Second, the above passage contradicts itself: it declares that eyewitnesses are especially unreliable when recalling events which are spectacular or fast-moving, but then it says that people are no better at recalling more mundane events. You can’t have it both ways. If people are relatively bad at recalling fast-paced or spectacular events, then they must be much better at recalling ordinary events that take place at a more leisurely pace.

Finally, if we actually compare the Gospel accounts of Jesus walking on water in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and John, what is remarkable is their essential agreement on core details, as well as the relative lack of embellishment in the narratives (St. John’s account, for instance, is just six verses long, while St. Mark’s narrative takes up nine verses). Here’s how Wikipedia summarizes the narratives:

In all three accounts, during the evening the disciples got into a ship to cross to the other side of the Sea of Galilee, without Jesus who went up the mountain to pray alone. John alone specifies they were headed “toward Capernaum”. During the journey on the sea the disciples were distressed by wind and waves, but saw Jesus walking towards them on the sea. John alone specified that they were five or six kilometers away from their departure point. The disciples were startled to see Jesus, but he told them not to be afraid.

Matthew’s account adds that Peter asked to come unto Jesus on the water… Matthew also notes that the disciples called Jesus the Son of God…

In all three accounts, after Jesus got into the ship, the wind ceased and they reached the shore. Only John’s account has their ship immediately reach the shore.

Could the gospel accounts be based on false memories?

Bethune also suggests in his article that the Gospel stories about Jesus may be based on false memories:

False memories are easily implanted. Just imagining being at an unusual event — seeing Lazarus rise from the dead, say — can cause a hearer to “remember” being personally present. A group of students in one test Ehrman cites were led, one by one, to a Pepsi machine; half were asked to get down on one knee and propose to it, the other half to imagine doing so. Two weeks later, half of the second cohort remembered actually making the marital offer.

There are four things wrong with this argument. First, on Ehrman’s scenario, some powerful “master-manipulator” would still have been required, in order to to implant false memories in the minds of Jesus’ highly suggestible disciples. Who was this mysterious person, and what was their motive?

Second, the implantation of a false memory of the sort described in Ehrman’s experiment presupposes that there was an unusual event to begin with. In the absence of the event, the motivation for people to imagine themselves having being there simply disappears.

Third, where are the imaginary witnesses in the Gospels? If we examine St. John’s account of Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead, the only people who are said to be present are Jesus’ disciples (who always accompany Him on His travels, and who are not named in the story anyway, with the exception of Thomas) and two sisters, Martha and Mary, who live in the same village as Lazarus, and who send word to Jesus that Lazarus is sick, shortly before he passes away. It would difficult to come up with a shorter list of eyewitnesses than these individuals.

Fourth, the experiment described by Ehrman is an extremely artificial one, which involved a group of people being led to a place and asked to deliberately imagine performing a very bizarre action (proposing to a machine) which (for half of the subjects) they didn’t actually do. The experimental subjects (a group of college students) were happy to comply with this odd request. But in real life, people don’t usually do odd things like that. Why? Because they have absolutely no motive to do so.

How reliable is group memory?

Lastly, Bethune attacks the reliability of group memory, noting that it can easily be “enhanced” by the dominant member of the group:

Group memory was often the worst, according to anthropologists who watched it distort before their eyes when they recorded several witnesses at once. If a dominant member of the group interjected his version or a new (and potentially suspect) detail, the others would often let it slide unchallenged, incorporating it into the new collective memory.

Bethune makes a valid point here about the reliability of group memory, but fails to ask the deeper question: what kinds of details does the dominant member of a group typically insert into a narrative, anyway? Presumably, self-serving details which place that individual at the center of the action, and present that individual in a favorable light. So why is it, then, that Peter, who was by all accounts the leader of the twelve apostles (the name Jesus gave him means “Rock”), is described in all four Gospels as denying Jesus three times? And why does Jesus rebuke him and call him “Satan” in St. Matthew’s Gospel? And why are James and John, the other two prominent apostles, reproached for wanting to sit on Jesus’ right and left hand, when He comes again in glory?

I should add that there is not the slightest evidence in the psychological literature of mass hallucinations ever having occurred. (Some skeptics have claimed that the “miracle of the Sun” observed by 70,000 people in the Portuguese town of Fatima on October 13, 1917, constitutes a mass hallucination, but this claim is refuted by the fact that the miracle was witnessed independently at a distance of many kilometers. A more likely explanation is that solar miracles, which have been witnessed at many different places, are retinal after-images produced after religiously charged pilgrims were encouraged to stare at the sun for a prolonged period of time. In any case, such events have no bearing on the miracles attributed to Jesus, which were publicly witnessed under normal lighting conditions.)

D. Bethune’s hyper-skepticism: Is Jesus a myth?

Not content with his demolition of the Gospels, Bethune moves on to new ground. He proposes, more controversially, that Jesus may not have even existed in the first place:

…Pilate is in Mark as the agent of Jesus’s crucifixion, from which he spread to the other Gospels, and also in the annals of the Roman historian Tacitus and writings by his Jewish counterpart, Josephus. Those objective, non-Christian references make Pilate as sure a thing as ancient historical evidence has to offer, unless — as has been persuasively argued by numerous scholars, including historian Richard Carrier in his recent On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason For Doubt — both brief passages are interpolations, later forgeries made by zealous Christians.

Snap that slender reed and the scaffolding that supports the Jesus of history— the man who preached the Sermon on the Mount and is an inspiration to millions who do not accept the divine Christ — is wobbling badly.

I have summarized the historical evidence for Jesus’ existence in a previous post. I shall briefly re-present it here.

|

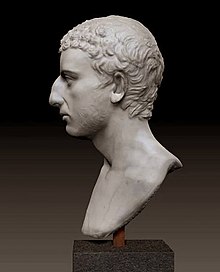

Photograph of a Roman portrait bust, said to be of Josephus. The 1st century Roman portrait bust is conserved in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, Denmark. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Josephus (A.D. 37 – c.100) may have been born a few years after the death of Jesus, but he was a personal eyewitness of the execution of Jesus’ brother, James (who may have actually been a half-brother or cousin of Jesus), in 62 A.D.

Atheist Paul Tobin, creator of the skeptical Website The Rejection of Pascal’s Wager, has written an excellent article, The Death of James, in which he argues for the historical trustworthiness of Josephus’ description of the execution of James, whom he refers to as “the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ”:

The timing of the incident, the interregnum between Festus and Albinus, allows us to date this quite accurately to the summer of 62 CE. [1] Our confidence in the historicity of this account is bolstered by the fact that it was probably an eye witness account. Josephus mentioned in his Autobiography that he left Jerusalem for Rome when he was twenty-six years old. He date of birth was most likely around 37 CE. So at the time of James’ execution, the twenty five year old Josephus was a priest in Jerusalem.

The atheist amateur historian Tim O’Neill has written several blog posts rebutting the arguments of modern-day skeptics who deny the historicity of Jesus. O’Neill has no theological ax to grind here: indeed, he declares that he “would have no problem at all embracing the idea that no historical Jesus existed if someone could come up with an argument for this that did not depend at every turn on strained readings.” O’Neill exposes the shoddy scholarship of these &”Mythers” (as he calls them) in a savagely critical review of “Jesus-Myther” David Fitzgerald’s recent book, Nailed: Ten Christian Myths that Show Jesus Never Existed at All. In the course of his lengthy review (dated May 28, 2011), O’Neill summarizes the evidence for Jesus’ historicity from the works of Josephus (bold highlighting mine – VJT):

As several surveys of the academic literature have shown, the majority of scholars now accept that there was an original mention of Jesus in Antiquities XVIII.3.4 and this includes the majority of Jewish and non-Christian scholars, not merely “wishful apologists”. This is partly because once the more obvious interpolated phrases are removed, the passage reads precisely like what Josephus would be expected to write and also uses characteristic language found elsewhere in his works. But it is also because of the 1970 discovery of what seems to be a pre-interpolation version of Josephus’ passage, uncovered by Jewish scholar Schlomo Pines of Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Professor Pines found an Arabic paraphrase of the Tenth Century historian Agapius which quotes Josephus’ passage, but not in the form we have it today. This version, which seems to draw on a copy of Josephus’ original, uninterpolated text, says that Jesus was believed by his followers to have been the Messiah and to have risen from the dead, which means in the original Josephus was simply reporting early Christian beliefs about Jesus regarding his supposed status and resurrection. This is backed further by a Syriac version cited by Michael the Syrian which also has the passage saying “he was believed to be the Messiah”. The evidence now stacks up heavily on the side of the partial authenticity of the passage, meaning there is a reference to Jesus as a historical person in precisely the writer we would expect to mention him…

The second mention is made in passing in a passage where Josephus is detailing an event of some significance and one which he, as a young man, would have witnessed himself.

In 62 AD, the 26 year old Josephus was in Jerusalem, having recently returned from an embassy to Rome. He was a young member of the aristocratic priestly elite which ruled Jerusalem and were effectively rulers of Judea, though with close Roman oversight and only with the backing of the Roman procurator in Caesarea. But in this year the procurator Porcius Festus died while in office and his replacement, Lucceius Albinus, was still on his way to Judea from Rome. This left the High Priest, Hanan ben Hanan (usually called Ananus), with a freer rein that usual. Ananus executed some Jews without Roman permission and, when this was brought to the attention of the Romans, Ananus was deposed.

This was a momentous event and one that the young Josephus, as a member of the same elite as the High Priest, would have remembered well. But what is significant is what he says in passing about the executions that that triggered the deposition of the High Priest:

Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so (the High Priest) assembled the sanhedrin of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Messiah, whose name was James, and some others; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned.

…A major part of the problem with most manifestations of the Myther thesis is that its proponents desperately want it to be true because they want to undermine Christianity. And any historical analysis done with one eye on an emotionally-charged ideological agenda is usually heading for trouble from the start… Their biases against Christianity blind Mythers to the fact that they are not arriving at conclusions because they are the best or most parsimonious explanation of the evidence, but merely because they fit their agenda.

The overwhelming majority of scholars, Christian, non-Christian, atheist, agnostic or Jewish, accept there was a Jewish preacher as the point of origin for the Jesus story simply because that makes the most sense of all the evidence... Personally, as an atheist amateur historian myself, I would have no problem at all embracing the idea that no historical Jesus existed if someone could come up with an argument for this that did not depend at every turn on strained readings, ad hoc explanations, imagined textual interpolations and fanciful suppositions.

In his article, Brian Bethune cites the work of Richard Carrier, author of the recently released book, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason For Doubt. In order to illustrate the book’s central flaws, I’d like to quote from one fair-minded reviewer:

In his preface, Dr Carrier endeavours at length to distance himself from the kooks and conspiracy theorists that Jesus-is-Myth advocates are usually associated with by serious scholars. And accordingly, the sources he professes to use are sound: peer-reviewed articles and books by credible specialists only, etc. The breadth of his scholarship is also beyond question. Throughout, the book reads like the publication of a trained and serious historian, which he is.

However, his methodology is slightly more dubious: he states from the outset that he will try to make the best case possible for a Jesus-Myth theory. This is not how a historian works. One does not compile evidence for a foregone conclusion; one draws the conclusion from the evidence.

And sure enough, the conclusion is deeply flawed: according to Dr Carrier, Jesus started out as a myth, then people sort of forgot that he was a myth, and started believing that he was a historical figure. Even supposing the entire early Christian community somehow developed early-onset Alzheimer’s at some point, this forgetfulness theory doesn’t hold water… Luke, for instance, explicitly states that he “painstakingly collected all the evidence, primarily from eyewitnesses”. Dr Carrier would be much more credible if he argued for deliberate deceit, but that would put him back into uncomfortable proximity with the conspiracy theorists...

The core of the problem seems to be that Dr Carrier, trained historian though he is, doesn’t seem able to comprehend the Ancients’ attitude towards historical narrative. They may mess with chronology to present events in an order better suited to the theological points they wish to make; or blend accepted traditions with hard facts when sourced evidence is lacking (though this is only considered acceptable when dealing with the distant past). Making stuff up completely, on the other hand, especially if you go to the lengths of feverishly researching the names of Galilean hamlets with a population of about 15 to make the rest look more credible, would be outright fraud, as much back then as now today. Read Plutarch’s “de Herodoti malignitate” for a period-correct take on the subject.

But all these remarks pale next to the main concern: Dr Carrier, seemingly so concerned with eschewing kookery in his preface, dives straight into it with his Bayesian probability conceit. There is no value in applying probability to history. History is the knowledge of what happened, no matter how improbable. It was improbable for the Greeks to win at Marathon, for Alexander to conquer half of Asia, for a racist Austrian corporal to draw the whole world into a 5-year war. And yet it happened. History isn’t science. Deal with it. Using numbers and equations in a field that doesn’t call for them doesn’t make you look more serious, it makes you look like a lunatic, or a simple-minded soul who took the advice that the only thing an atheist should believe in is Science a little too literally. Same thing applies, on a lesser scale, to the Rank-Raglan index. Just because it has a numerical value doesn’t mean the numbers impart a magical quality of scientific rigor to everything they touch. Jesus scores a 20 on this scale. So what? Abraham Lincoln scores a 22, and Harry Potter an 8. So Jesus is a little more historical than Lincoln, but a lot less than Harry Potter? I didn’t think so.

I’ll let Canadian apologist Andy Steiger have the last word on Bethune’s article:

What Bethune’s article does show us is a textbook example of amateur, agenda-driven writing that you would expect from a high schooler with a bad attitude or a rant on Reddit. Not only are no Christian historians referenced in this article (by the way, Bart Erhman’s wife is one of those), but the article gives a glowing and unsupported review of mythicists. Lastly, the logic. If Ehrman’s book were correct— and it’s not—it would only show that the New Testament is unreliable. This is a far cry from saying that Jesus as a historical figure didn’t exist.

In sum, I have no idea how this article got into a magazine like Maclean’s, let alone on the front cover, but I’m not sure if I should weep or laugh.

Maclean’s, we expect better from you!

E. Conclusion

To give credit where credit is due, Professor Bart Ehrman, in his recent scholarly attack on the reliability of the New Testament, at least took the trouble to draw upon the latest scientific research relating to the fallibility of human memory, even though he overlooked equally impressive research demonstrating the reliability of memory, both within a community and within the mind of an eyewitness, over the course of time. However, Brian Bethune’s hatchet job on Jesus attempts to cast doubt on His very existence, citing the work of one historian (Richard Carrier) who is not recognized as a New Testament scholar, and whose methodology is highly dubious. I am forced to conclude that Bethune’s article is not based on sound scholarship; it bears all the hallmarks of being ideologically motivated.

What do readers think?