|

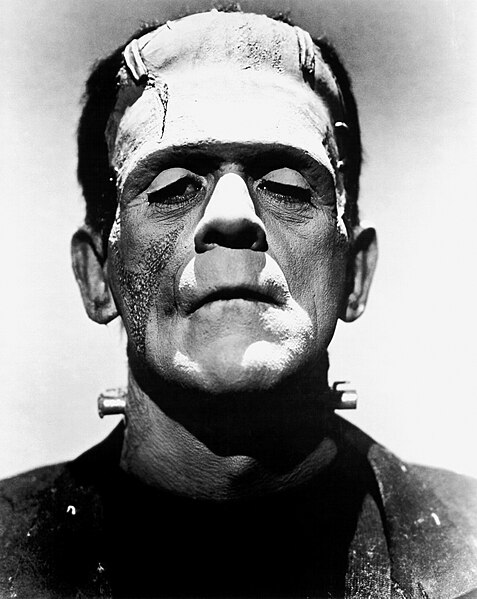

Here’s a technological advance that should make us all go “Whoa!”: a neuroscientist says it’s now possible to graft one person’s head onto another person’s body, and to connect the transplanted head to the spinal cord of the body it’s grafted onto. The obvious question for dualists is: what would happen to the human soul, if such a hellish operation were ever carried out?

Dr. Sergio Canavero, a member of the Turin Advanced Neuromodulation Group, explains that successful head transplants have been carried out on animals since 1970, but they were always paralyzed below the neck, as scientists were never able to connect the spinal cord from the head to that of the body it was transplanted into. Even now, the connection of a spinal cord from the head of one animal to the body of another has yet to be accomplished. However, in a recent paper, Dr. Sergio Canavero contends that it could be done. A report by Christopher Mims (1 July 2013) in QUARTZ describes the technique:

…By cutting spinal cords with an ultra-sharp knife, and then mechanically connecting the spinal cord from one person’s head with another person’s body, a more complete (and immediate) connection could be accomplished. As he [Dr. Canavero] notes in his paper:

“It is this “clean cut” [which is] the key to spinal cord fusion, in that it allows proximally severed axons to be ‘fused’ with their distal counterparts. This fusion exploits so-called fusogens/sealants….[which] are able to immediately reconstitute (fuse/repair) cell membranes damaged by mechanical injury, independent of any known endogenous sealing mechanism.”

Canavero hypothesizes that plastics like polyethylene glycol (PEG) could be used to accomplish this fusing, citing previous research showing that, for example, in dogs PEG allowed the fusing of severed spinal cords.

A certain degree of skepticism is warranted until the technique described by Dr. Canavero has been demonstrated. But I think it’s fair to say that the head transplant scenario has now moved from the realm of science fiction into the realm of the feasible.

The conundrum facing dualists

So if Smith’s head is transplanted into Jones’ body, whose soul does the human being after the transplant possess? Four answers are possible:

1. Smith’s soul animates the body after the transplant, because even the human soul’s immaterial operations of reasoning, understanding and decision-making are physically implemented via the brain, while lower-level mental acts such as imagining, remembering, sensing and feeling intimately involve the brain (and in the case of seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and touching, the sensory organs as well, most of which are located in the head), but no part of the body below the neck is involved (except in the case of touch). Thus it seems logical to say that wherever the head goes, the soul goes. Additionally, none of the mental capacities listed above can be meaningfully attributed to Jones’ decapitated body.

2. Jones’ soul animates the body after the transplant, because the body is undeniably Jones’ body, and the soul is defined as being essentially the form of the human body – that which makes it a body as such.

3. A new soul animates the body after the transplant, because the individual after the operation can neither be described as Smith nor Jones, biologically speaking: it’s more of an amalgam of part of the two. A new body requires a new soul.

4. The individual after the transplant doesn’t have a human soul at all. He or she is just an animal.

I think we could definitively rule out 4 if the individual after the transplant proved to be capable of reasoning and moral decision-making, and of justifying his/her opinions and choices, using human language. I see no reason to doubt that the post-transplant individual would possess such capacities, so that leaves us with 1, 2 and 3.

Three varieties of dualism, and how they address the head transplant case

In my previous posts on split-brain patients (see here and here) I distinguished between three varieties of dualism – leaving aside property dualism, which leaves no scope for human freedom – namely, substance dualism, thought control dualism and formal-final dualism. NOTE:I’ve decided to rechristen “thought control dualism” as “body control dualism,” following a tip from KeithS, who suggested a name change in a recent post of his, since “thought control” has rather sinister overtones. I believe the new name is quite apt, because according to this version of dualism, the human soul doesn’t merely inform the body; it also controls the body. (I leave open the question of whether this kind of soul-body control also occurs to some limited degree in the “higher animals.”)

It should be readily apparent that the head transplant case poses no problem for substance dualists, who would say that the soul (or self) goes with the head which it is causally connected to, and which it moves. The main problem with substance dualism, as Aquinas astutely pointed out, is that it fails to account for the unity of the self – i.e. the fact that we say that it is one and the same “I” who thinks, senses, feels, eats, grows and so on. According to substance dualism, only my mental acts are properly mine; everything else about me should properly be ascribed to another entity: my body.

Unlike substance dualism, which envisages the soul as a separate thing from the body, body control dualism and formal-final dualism both agree that the soul is essentially the form of the human body. However, whereas body control dualism views an organism’s form as being a hierarchical structure which informs the body at multiple levels and is capable of interacting with the brain, formal-final dualism regards an organism’s form as being determined by its built-in goals or ends, just as a knife’s form is determined by its function of cutting.

A formal-final dualist would argue that a severed head is not a body by any stretch of the imagination, and that since the soul essentially informs the whole body, the only candidate for a body surviving the operation is Jones’. A formal-final dualist would also add that mental capacities such as sensing, feeling, imagining and remembering cannot meaningfully be attributed to the brain alone, or even to the brain plus the sensory organs, but only to the whole person: it is I who sees, not my brain or my eyes. Hence it is a category mistake to infer that wherever Smith’s head goes, his mental capacities go. For a formal-final dualist, then, the only options deserving serious consideration are 2 and 3.

The only question remaining for a formal-final dualist is whether we have any good reason to believe that Jones’ body survives the head transplant operation. I can think of no good reason why a formal-final dualist would deny this. Since Jones’ body, before and after the transplant, has the same built-in goals or ends, then a formal-final dualist would have to say that it has the same soul. On this view, the patient’s identity is no more altered by the operation than it would be by a heart transplant operation.

A body control dualist, on the other hand, would have to ask whether the hierarchical structure of Jones’ soul, which informs the body at multiple levels, is preserved in the head transplant operation. And it should be pretty obvious that it is not: the soul’s higher faculties, which are either immaterial (intellect and will) or which intimately involve the brain (e.g. imagination, memory, the senses and the passions) are no longer present in the decapitated body of Jones. Hence it seems we can rule out option 2: the individual after the transplant is definitely not Jones.

The brain’s vital role in integrating the vegetative functions of the body

What about the lower, vegetative faculties, such as nutrition and growth? If these were still present in Jones’ decapitated body, then one could argue that Jones is still the same organism, after the transplant, and therefore has the same soul. However, Professor Maureen Condic, in a pro-life article in First Things (May 2003) entitled, Life: Defining the Beginning by the End, argues that in mature individuals – as opposed to early embryos – the ability of all cells in the body to function together as an organism depends vitally on the functioning of the whole brain:

What has been lost at death is not merely the activity of the brain or the heart, but more importantly the ability of the body’s parts (organs and cells) to function together as an integrated whole. Failure of a critical organ results in the breakdown of the body’s overall coordinated activity, despite the continued normal function (or “life”) of other organs. Although cells of the brain are still alive following brain death, they cease to work together in a coordinated manner to function as a brain should. Because the brain is not directing the lungs to contract, the heart is deprived of oxygen and stops beating. Subsequently, all of the organs that are dependent on the heart for blood flow cease to function as well. The order of events can vary considerably (the heart can cease to function, resulting in death of the brain, for example), but the net effect is the same. Death occurs when the body ceases to act in a coordinated manner to support the continued healthy function of all bodily organs. Cellular life may continue for some time following the loss of integrated bodily function, but once the ability to act in a coordinated manner has been lost, “life” cannot be restored to a corpse — no matter how “alive” the cells composing the body may yet be.

What does the nature of death tell us about the nature of human life? The medical and legal definition of death draws a clear distinction between living cells and living organisms. Organisms are living beings composed of parts that have separate but mutually dependent functions. While organisms are made of living cells, living cells themselves do not necessarily constitute an organism. The critical difference between a collection of cells and a living organism is the ability of an organism to act in a coordinated manner for the continued health and maintenance of the body as a whole. It is precisely this ability that breaks down at the moment of death, however death might occur. Dead bodies may have plenty of live cells, but their cells no longer function together in a coordinated manner. We can take living organs and cells from dead people for transplant to patients without a breach of ethics precisely because corpses are no longer living human beings. Human life is defined by the ability to function as an integrated whole — not by the mere presence of living human cells.

Professor Condic goes on to argue that persons in a persistent vegetative state, whose brainstems continue to function normally, retain their integrated bodily function and are therefore fully alive, as are early embryos whose brains have not yet developed:

Embryos are not merely collections of human cells, but living creatures with all the properties that define any organism as distinct from a group of cells; embryos are capable of growing, maturing, maintaining a physiologic balance between various organ systems, adapting to changing circumstances, and repairing injury. Mere groups of human cells do nothing like this under any circumstances.… Even within the fertilized egg itself there are distinct “parts” that must work together — specialized regions of cytoplasm that will give rise to unique derivatives once the fertilized egg divides into separate cells. Embryos are in full possession of the very characteristic that distinguishes a living human being from a dead one: the ability of all cells in the body to function together as an organism, with all parts acting in an integrated manner for the continued life and health of the body as a whole.

To summarize: in human beings who are old enough to have have acquired a brain, the brain plays a vital role not only in mental acts, but also in the integration of bodily functions. If we define the soul in terms of its hierarchical structure, in addition to its built-in ends, then it is clear that the brain is a privileged organ, which the body cannot lose without losing its very “bodiliness.” Hence it would be incorrect, in the hypothetical head transplant example discussed above, to describe Jones’ decapitated body as a body, in the absence of a brain.

An objection from Dr. Alan Shewmon: Does a human body really need a brain?

In an article titled, The Brain and Somatic Integration: Insights into the Standard Biological Rationale For Equating “Brain Death” With Death (Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 2001, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 457-478), Dr. D. Alan Shewmon argues that the brain’s alleged role in integrating the body has been much over-hyped. The abstract of his article provides a handy summary of his reasoning:

The mainstream rationale for equating ‘brain death’ (BD) with death is that the brain confers integrative unity upon the body, transforming it from a mere collection of organs and tissues to an ‘organism as a whole’. In support of this conclusion, the impressive list of the brain’s myriad integrative functions is often cited. Upon closer examination and after operational definition of terms, however, one discovers that most integrative functions of the brain are actually not somatically integrating, and, conversely, most integrative functions of the body are not brain-mediated. With respect to organism-level vitality, the brain’s role is more modulatory than constitutive, enhancing the quality and survival potential of a presupposedly living organism. Integrative unity of a complex organism is an inherently nonlocalizable, holistic feature involving the mutual interaction among all the parts, not a top-down coordination imposed by one part upon a passive multiplicity of other parts. Loss of somatic integrative unity is not a physiologically tenable rationale for equating BD with death of the organism as a whole.

Shewmon concludes:

Integration does not necessarily require an integrator, as plants and embryos clearly demonstrate. What is of the essence of integrative unity is neither localized nor replaceable – namely the anti-entropic mutual interaction of all the cells and tissues of the body, mediated in mammals by circulating oxygenated blood. To assert this non-encephalic essence of organismal life is far from a regression to the simplistic traditional cardio-pulmonary criterion or to an ancient cardiocentric notion of vitality. If anything, the idea that the non-brain body is a mere ‘collection of organs’ in a bag of skin seems to entail a throwback to a primitive atomism that should find no place in the dynamical-systems-enlightened biology of the 1990s and twenty-first century.

Why your body needs a brain

I would like to say that I have the greatest respect for Dr. Shewmon. However, it seems to me that his philosophical arguments in favor of the holism that he is advocating are inconclusive. Dr. Jason T. Eberl, Associate Professor of Philosophy at the Indiana University School of Liberal Arts at IUPUI, has written a rebuttal of Dr. Shewmon’s arguments in an article titled, “Whole-Brain-Dead Individuals” in The ethics of organ transplantation edited by Steven J. Jensen (Washington, D.C. : Catholic University of America Press, 2011). I’d like to quote a few relevant excerpts:

As the principle of a human body’s organic functioning, Aquinas understands the soul to operate by means of a “primary organ,” which he identifies with the heart; although it seems that the brain better befits this role. Aquinas describes the primary organ as that through which the soul “moves” or “operates” the body’s other parts; it is the ruler of the body’s other parts in the sense that it orders them as a ruler orders a city through laws.

Eberl gives two references to back up his claim: Quaestio disputata de anima a. 10, ad. 4, where Aquinas states that “the body’s principle of motion exists in one part, namely, in the heart, and moves the whole body through this part,” and De motu cordis, where Aquinas writes that “the movements of all the other parts of the body are caused by the heart, as the Philosopher proves in On the Motion of Animals (703a14).” “The Philosopher” is of course Aristotle, who regarded the heart as the seat of thought. On this point, Aristotle was of course mistaken: he was following the views of the Sicilian medical school of his day. Even in Aristotle’s time, however, there were farsighted Greek thinkers, such as Hippocrates and Empedocles, who realized that the brain was the organ of the body associated with thought.

The point here is that Aquinas adhered to a hierarchical view of the body’s organs, with a primary organ at the top, governing and ordering the movements of the other parts. Today we would identify this primary organ with the brain. This comports well with body control dualism, which defines the soul not only in terms of its built-in ends but also its hierarchical structure, which is manifest in the way that the body’s movements are regulated.

Dr. Eberl goes on to address Dr. Shewmon’a arguments against equating biological death with whole-brain death. Citing Aquinas in support of his views, he argues forcefully that a whole-brain-dead individual whose respiration and blood circulation are being maintained by a mechanical ventilator or cardiopulmonary bypass machine is no longer alive, and that the bodily functions manifested in such an individual can no longer be attributed to that individual. Hence they cannot legitimately be used to back up Dr. Shewmon’s contention that a wide range of bodily functions don’t require the brain to integrate them, and that the brain is therefore more of a “fine-tuner” than a governing organ of the body:

Shewmon rejects the whole-brain criterion after examining cases in which a human body appears to maintain its integrative unity after whole-brain functioning has irreversibly ceased. Such cases lead Shewmon to conclude that the brain does not function as the body’s central organizer. Rather, Shewmon argues that the brain “fine-tines” the vital functions that the body itself exercises as an integrative whole…

If, as Shewmon argues, a body can maintain its integrative unity without any brain function, then whole-brain death cannot be equated with a human organism’s death. Shewmon thus advocates a circulatory/respiratory criterion for determining when death occurs.

Shewmon appeals to a number of cases in which a whole-brain-dead individual appears to exhibit somatic integrative functioning. The most provocative cases are those in which patients are properly diagnised as whole-brain-dead and yet survive for extended periods of time with technological and pharmacological support. Despite the requirement of mechanical ventilation for respiration and circulation of oxygenated blood to occur, Shewmon contends that these cases exhibit integrative unity by virtue of exercising the somatic functions listed above [viz. “homeostasis of various interacting chemicals, cellular waste handling, energy balance, maintenance of body temperature, wound healing, infection fighting, stress responses, proportional growth, and even sexual maturation” – VJT.] He thus concludes that these patients cannot be considered dead, even though they lack whole-brain function.

If, as Shewmon maintains, integrative vegetative operations can remain in a whole-brain-dead human body, one ought to conclude that a rational soul continues to inform such a body until it ceases its vital functions of circulation and respiration… [However], there are several issues that can be raised about the cases Shewmon uses to support his conclusion and the inferences he draws.

Shewmon describes a human brain as more a “regulator” or “fine-tuner” of a body’s vital functions, rather than being constitutive of them. It does not seem, however, that this distinction makes a real difference in criticizing the whole-brain criterion. While brainstem functioning is certainly not solely responsible for the vital functions of circulation and respiration, a human body cannot carry out such functions on its own in the absence of brainstem functioning. The assumption of such functions by life-support machinery indicates that the body has lost the capacity to perform them under its own control. It thus remains arguable that integrative unity has been lost in such cases…

…Aquinas further defines a living animal’s vital function in a way which would preclude their being taken over by an artificial device and yet remaining functions of that animal: “Vital functions are those of which the principles are within the operators, such that the operators induce such operations of themselves.” [Ref. Summa Theologica I, q. 18, art. 2, ad. 2 – VJT.]

Dr. Eberl concludes that if a human being’s vital functions are being performed by a mechanical ventilator, then “such functions and the capacity for performing them are no longer attributable to the individual dependent upon such a device.” He adds that an individual who is irreversibly dependent upon such support cannot properly be said to possess an “active potentiality” to exercise the vegetative functions that characterize organisms. Rather, such an individual has only a “passive potentiality” to receive oxygenated air which is introduced and circulated throughout her body. Dr. Eberl cites the opinion of Bishop Marcelo Sanchez Sorondo, the current Chancellor of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, that such an individual is no longer alive:

The instrument-ventilator becomes the principal cause that holds together the sub-systems which previously had a natural life, but which now, with their actions conserved mechanically, have the appearance of a living organism. In reality, to be precise, since the soul is no longer present, the life we see is an artificial one, with the ventilator delaying the inexorable process of the corruption of the corpse.

(Marcelo Sanchez Sorondo, ed. The Signs of Death. The Proceedings of the Working Group 11-12 September 2006, Scripta Varia 110, Vatican City, Pontifical Academy of Sciences 2007, xliii.)

Readers who are interested might like to have a look at the document, Why the Concept of Death is Valid as a Definition of Brain Death, a statement by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences with Responses to Objections by Professor Spaemann and Dr. Shewmon (Extra Series 31, Vatican City, 2008).

Dr. Eberl concludes that a human body ceases to be a body when it loses the capacity to control its own vital functions of circulation and respiration:

…A human body loses integrative unity when it no longer has the active potentiality to co-ordinate the vital functions of circulation and respiration, and such functions can only be maintained by artificial means. The clinical sign that this capacity has been lost is the irreversible loss of spontaneous heartbeat and respiration. These two vital functions are emphasized insofar as the circulation of oxygenated blood throughout the body is the fundamental biological requirement for any and all organic activity in the absence of technological replacement. While other functions such as digestion, waste excretion, and immune response – are also vital for an organism to survive, the respective organs associated with these functions are dependent upon oxygenated blood being circulated through them. Thus the form of dependency a whole-brain-dead individual has with respect to a mechanical ventilator or functionally similar device is quite different from that of a living human being who requires a pacemaker, or some such device, to regulate her vital functions.

Furthermore, Shewmon’s conclusion that certain functions are “integrative” just because they are holistic does not follow…

I conclude that a human body’s having control over its vital functions of circulation and respiration is a necessary criterion for it to have integrative unity; these specific activities are the vital functions necessary for somatic integrative unity insofar as all other organs of the body depend upon oxygenated blood circulating through them in order to survive and function. Shewmon’s case for abandoning the whole-brain criterion depends upon there being cases in which spontaneous heartbeat and respiration occur in the absence of whole-brain functioning, and he has not presented any such case.

While I agree with Shewmon, contra Lizza, that an organism which has suffered the irreversible loss of higher-brain function may continue to be rationally ensouled – and thereby compose a human person – Shewmon’s extension of this conclusion to a whole-brain-dead body appears to be, as Lizza terms it, “vitalism run amok.”

The upshot of Dr. Eberl’s argument vis-a-vis the head transplant case (where Smith’s head is transplanted onto Jones’ body) is that we cannot legitimately speak of a body living without a head, since a brainstem is required to regulate spontaneous heartbeat and respiration in a living individual. Thus if Jones’ body is decapitated, it is no longer a body.

But what about Smith’s severed head? Can it be called a body? And can it still be said to possess Smith’s soul, if that soul has no body of its own to inform? To shed light on these difficult questions, Dr. Eberl considers a case which should be familiar to us all: the late Christopher Reeve (1952-2004), whose spinal cord was severed when he was thrown from a horse in 1995.

Superman to the rescue

|

In his article, “Whole-Brain-Dead Individuals,” Dr. Eberl goes on to discuss two cases – one real and one hypothetical – put forward by Dr. Shewmon to support his challenge to the whole-brain criterion. The first case involves high cervical cord transection, the injury suffered by the late Christopher Reeve. The interesting thing about this case, as Dr. Eberl explains, is that it is functionally equivalent to whole brain death:

High cervical cord transection involves a structural separation between the upper vertebrae and the brainstem, as in the injury suffered by the late Christopher Reeve when he was thrown from a horse. This structural separation results in the loss of communication between the brainstem and the rest of the body. Patients in this condition are conscious and able to control the parts of their body that remain neurally connected to the brain above the transection – for example, facial muscles, eyes and mouth – but they cannot spontaneously respire and must be connected to a mechanical ventilator. This condition is thus functionally equivalent to whole-brain-death.…

Dr. Eberl, in discussing this case, argues for a conclusion which may strike some as counter-intuitive, but which makes perfect sense if we view the brain as the body’s “central organizer”: he argues that Christopher Reeve’s body below the neck was no longer his body, properly speaking, following the accident he suffered.

…[G]iven that life-support machinery cannot become a proper part of a human body’s substantial unity and that a body dependent upon artificial support for its vital functions cannot have integrative unity, it follows that the body of a patient with high cervical cord transection is no longer informed by his rational soul below the point of the transection. The patient remains conscious and able to control his body above the level of the transection, which indicates that he is alive and informed by his rational soul; but his soul now informs only his head and those parts of his body which his brain can still control, such as motor control over his facial muscles and other parts of his head such that he can communicate, grimace, move his eyes, etc. The rest of the body, though still structurally joined to him, is no longer a proper part of him, because it no longer participates in his integrative organic functioning. With the help of artificial life support, the rest of the body continues to circulate oxygenated blood to the brain, which allows it to continue functioning and the patient to remain conscious. This relationship, though, of body to brain is no different than if the patient’s head were severed and connected to an external mechanical pump, as will be discussed below; neither the pump nor the body are proper parts of the patient.…

However, while the body attached to Christopher Reeve’s head was not properly a part of him, Dr. Eberl points out that the individual cells in that body were still alive, thanks to the mechanical ventilator. Consequently, if the body could have been surgically reconnected to Christopher Reeve’s head, then it would have become part of his body, properly speaking, once more, and his soul would have then informed it:

If a patient with high cervical cord transection regains functional unity of his brainstem with the body reconnected to him by having the neural tissue or an artificial electrical conductor grafter onto the spinal cord to eliminate the transection, then his rational soul would re-inform the body owing to the reinstatement of the brainstem’s control over the body’s vital functions.

The curious case of the headless corpse

Dr. Eberl then considers a hypothetical thought experiment proposed by Dr. Shewmon, involving decapitation of a person, followed by artificial support of both the body and the severed head, which is still conscious. This is very close to the head transplant case which is the topic of this post. Dr. Shewmon argues that if the body is mechanically ventilated, it still exhibits integrated functionality and is still an organism as a whole, an argument which Dr. Eberl rejects:

Concerning the ontological status of the decapitated body, Shewmon asks: “Is the ventilated, non-bleeding and headless body a terminally ill ‘organism as a whole’ or a mere unintegrated collection of living organs and tissues? Based on the above considerations, I conclude that the latter is the case, in agreement with Bernat:

There is an important distinction to be made between an organism on the whole on one hand, and the whole organism on the other. If you remove a limb from a human, that in no way disturbs the organism as a whole. Although it is true that some aspects of the organism may not be present solely in the head portion of this thought experiment… the head portion, who is able to communicate, think and experience, would represent the person and not the body portion, which is analogous to the brain dead patient.

Dr. Eberl points out that Dr. Shewmon himself acknowledges that the severed but still conscious head possesses a rational soul of its own. What that means is that in the hypothetical case of a single person whose head and decapitated body are maintained separately, we would have to posit two distinct souls – a very messy solution.

But is a conscious head an organism?

There remains one more objection for Dr. Eberl to address: the objection that a severed head (conscious or not) is not an organism, and therefore cannot (according to the Thomistic view) be said to have a soul.

Dr. Eberl solves this conundrum by acknowledging that a severed head is not an organism, but insisting that it is still an animal, as it still possesses (unactualized) sensitive and vegetative capacities. According to Aquinas, a human being is essentially an animal, but Eberl thinks it is only a contingent fact that human beings are organisms. Eberl argues that it is (technically) possible for an animal to exist without being composed of a material, organic body.

Summary

To sum up: there seems to be no good reason to deny the common intuition that in the head transplant case where Smith’s head is transplanted onto Jones’ body, the person after the transplant would be Smith, and not Jones or some new individual.

Let us all devoutly hope that no-one ever carries out the bizarre experiment of a head transplant on human beings. The point of this post, however, was to show that dualists have a ready response to the question of what would happen to the human soul, if such a hideous operation were ever carried out. Head transplant cases pose no threat to dualism.