|

Over at Heather’s Homilies, Heather Hastie has written a post titled, Is New Atheism a Cult?, in which she argues convincingly for the negative position. Cults tend to share certain characteristics which, by and large, don’t apply to New Atheism:

- The group members display an excessively zealous, unquestioning commitment to an individual.

- The group members are preoccupied with bringing in new members.

- Members are expected to devote inordinate amount of time to the group.

- Members are preoccupied with making money.

- Members’ subservience to the group causes them to cut ties with family and friends, and to give personal goals and activities that were of interest to the group.

- Members are encouraged or required to live and/or socialize only with other group members.

The definition used by Hastie is borrowed from the American Family Foundation, a Christian charity whose activities include rescuing people from cults. While Hastie acknowledges that “there are certainly some people who show excessive admiration towards the leaders of New Atheism,” she counters this by citing a remark by Richard Dawkins in The God Delusion, that trying to organize atheists is like trying to herd cats. I don’t think this is a very good response, as the vast majority of atheists are not New Atheists: most of them are closer to Alain de Botton than Richard Dawkins in their outlook on religion. The same point applies to the survey cited by Hastie and conducted by sociologist Dr. Phil Zuckerman, which found that atheists and secularists are “markedly less nationalistic, less prejudiced, less anti-Semitic, less racist, less dogmatic, less ethnocentric, less close-minded, and less authoritarian” than religious people. I have critiqued Dr. Zuckerman’s shoddy statistics in a previous post, but again, even if he were correct, his survey proves nothing about New Atheists.

A better response would have been to point out that the New Atheist movement has not one but several leaders, and that none of these leaders can command blind, unquestioning obedience in the way that the leader of a cult can do. The other characteristics of cults don’t really apply to the New Atheists either. Their main aim is not so much to win converts as to destroy belief in the supernatural. While some of them may spend a lot of time advocating atheism, none of them have given up their day-time jobs for the sake of devoting themselves to the cause. Nor do I know of any New Atheists who are actively involved in soliciting money from donors. And I have never heard of a New Atheist cutting ties with family members and friends, or living apart from society. In short: the term “cult” simply does not describe the New Atheists well.

I might add that a recent book purporting to show that New Atheism is a cult has been convincingly rebutted here and here.

But a cult is one thing, and a religion is quite another. In today’s post, I’m going to explain why I think that New Atheism can be fairly described as a religion.

Why a religion doesn’t have to involve belief in the supernatural

Let’s get two obvious objections out of the way immediately. First, many people would argue that since atheism is defined in purely negative terms, it cannot be legitimately referred to as a religion. Heather Hastie articulates this point very effectively in her post, Is New Atheism a cult?:

The important thing to note however, is that being an atheist does not bring with it any belief system whatsoever. There are dozens of analogies for this out there. Here are a few:

- Saying atheism is a religion is like saying “off” is a TV channel.

- Saying atheism is a religion is like saying bald is a hair colour.

- Saying atheism is a religion is like saying not playing golf is a sport.

- Sating atheism is a religion is like saying not collecting stamps is a hobby.

In response: while the foregoing analogies successfully rebut the notion that atheism is a religion, what they overlook is that there’s more to New Atheism than just atheism. New Atheism doesn’t just deny the existence of God; it also provides its adherents with a coherent philosophy of where we came from, where we’re going, what’s real and what’s not, and how we can know the difference. Insofar as it supplies a systematic set of answers to life’s big questions, New Atheism has quite a lot in common with religions such as Christianity and Buddhism. The question I will attempt to answer in this post is whether New Atheism deserves to be placed in the same category as these faiths.

Second, it is argued that since New Atheism rejects belief in the supernatural, it cannot possibly be called a religion. The problem with this argument is that by the same token, you’d have to say that Jainism (which views karma as acting in a purely mechanistic fashion and which utterly rejects the notion of a supernatural Creator) is not a religion. Confucianism and Taoism, which believe in a supreme cosmic order (called Tian or Tao) but not a supernatural Deity, would also fail to qualify as religions. And what about Gautama Buddha, who rejected the idea of a Creator God and a Cosmic Self, and who taught that even the Vedic spirit-beings (devas) are not important and need not be worshiped, because they have not yet attained enlightenment? If belief in supernatural deities is what defines a religion, then the Buddha cannot be called the founder of a religion.

I might add that according to the article on “Religion” in West’s Encyclopedia of American Law, 2nd edition (2008 The Gale Group, Inc.), belief in the supernatural is not a part of the legal definition of religion in American law, either:

The Supreme Court has interpreted religion to mean a sincere and meaningful belief that occupies in the life of its possessor a place parallel to the place held by God in the lives of other persons. The religion or religious concept need not include belief in the existence of God or a supreme being to be within the scope of the First Amendment…

In addition, a belief does not need to be stated in traditional terms to fall within First Amendment protection. For example, Scientology — a system of beliefs that a human being is essentially a free and immortal spirit who merely inhabits a body — does not propound the existence of a supreme being, but it qualifies as a religion under the broad definition propounded by the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has deliberately avoided establishing an exact or a narrow definition of religion because freedom of religion is a dynamic guarantee that was written in a manner to ensure flexibility and responsiveness to the passage of time and the development of the United States. Thus, religion is not limited to traditional denominations. (Emphases mine – VJT.)

A religion does, however, need to have an object of ultimate concern – something that its members care deeply about. For New Atheists, the object of ultimate concern is simply the flourishing of society itself: they believe that the world would be a much better place if society was entirely regulated by reason, and not faith. And this is something that the New Atheists care passionately about. The sheer volume of books that they have written in support of their cause in recent years attests to that fact.

Other distinguishing features of a religion

I would also argue that a religion has several other distinguishing features, which (as I’ll argue below) apply to New Atheism:

(a) a single, unifying explanation of what we are, where we came from and where we are going (Gauguin’s “big questions”);

(b) a set of prescriptions for members, which must not be deviated from (i.e. a “straight and narrow path”);

(c) a tendency for even minor alterations to either the religion’s factual claims or its prescriptions to yield conclusions which diverge radically from those taught by the religion;

(d) an epistemic theory describing how the claims made by the religion can be known to be true, by believers;

(e) some unresolved epistemic issues, relating to what we know and how we know it;

(f) the possibility of multiple and conflicting strategies for the advancement of the movement (i.e. evangelization); and

(g) a tendency to split into sects, due to (c), (e) and (f).

I imagine that readers will regard features (a) and (b) as fairly uncontroversial, although I should point out that some religions (such as Confucianism and to a lesser extent, Buddhism) are heavily pragmatic, and tend to discourage speculation about where we came from and where we are going. However, the contrast between speculative and pragmatic religions should not be overstated. Confucianism, for instance, attaches great importance to ancestor worship, and although it rejects belief in a personal Deity, its adherents often refer to the “Mandate of Heaven” (see also here). For its part, Buddhism has a very detailed cosmology, with multiple realms of existence, each inhabited by its own special kinds of beings, and there are also sects of Buddhism which offer vivid descriptions of the afterlife.

The other conditions which I have listed will probably raise some eyebrows. In short, what I’m claiming is that one of the defining characteristics of any religion is its built-in tendency to split into sects. (Even Confucianism, which is not an organized religion, has no less than eight different schools, while centuries ago, Buddhism split into as many as twenty sects.) Why is this so? What makes religions so prone to schism?

The impossibility of building a complete, epistemically closed system of thought

|

In 1931, the mathematician Kurt Godel demonstrated that the quest to find a complete and consistent set of axioms for all mathematics is an impossible one. The same, I would suggest, applies to religion. Since every religion propounds a set of truths, it needs to offer believers a set of epistemic principles which tell them how they can be sure that the beliefs they espouse are actually true. However, I would argue that any attempt to find an account of reality whose epistemic postulates (regarding what we can know and how we know it) are both self-justifying and capable of telling us how to answer any question we may want to ask about the world, is a vain one. With any system of thought, there will always be some unresolved issues about what we know and how we know it.

How minor changes in premises can yield radically divergent conclusions

Students of economics will be aware of the phenomenon of unstable equilibrium, where a model or system does not gravitate back to equilibrium after it is shocked. Consider the case of a marble sitting on top of an upside-down bowl. If the marble is nudged even slightly, it will roll off the bowl, without returning to its original position. In real life, markets with an unstable equilibrium are rare, although business-cycle contractions and stock market crashes are two probable cases in point. But if we look at systems of thought, unstable equilibrium is not the exception: it is the rule. I first became aware of this about a decade ago, when I was writing my Ph.D. thesis on animal minds. I had originally planned to include two chapters on our ethical obligations to animals and other living creatures, although in the end, I decided to cut them out and focus entirely on animal minds, in order to stay within my word limit. While writing these chapters on ethics, however, I was astonished to find that even minor changes in the ethical premises yielded drastically different conclusions, with regard to the extent of our obligations towards animals and other living things. I tried tightening them slightly or loosening them slightly, but all I did was see-saw back and forth, between extremes that were obviously either too burdensome on humanity (rendering even agriculture a morally dubious enterprise) or so permissive that they could be used to justify killing of animals and other creatures for practically any reason. Finding a sensible happy medium was very difficult, and in the end, I’m not sure if I really succeeded or not.

All religions enjoin their adherents to follow a “straight and narrow” path of some sort. What the foregoing considerations suggest to me is that religions, which attempt to codify our moral duties, might be susceptible to the same problem that beset me when I was trying to draw up a set of ethical principles that would govern our interactions with other living things. Minor changes in these principles can have drastic results, tending towards either a harsh moral rigorism or a self-satisfied laxism. And if we look at contemporary Christianity (and to a lesser extent, Judaism), it is striking to observe how differing attitudes towards the ultimate source of authority in religion have recently triggered rifts within Christian denominations (e.g. Anglicanism) over ethical issues (e.g. abortion, homosexuality and premarital sex) which dwarf the traditional divisions between denominations, so that an evangelical (low-church) Anglican will probably have more in common with a Baptist (say) than with a broad-church Anglican.

The “see-saw effect” that I noticed while writing on our duties towards animals isn’t limited to ethical matters. I would suggest that any kind of injunction – whether it concerns how we should think, what we should believe, what we should say or how we should act – is vulnerable to the same distortions, if modified. If we look at the history of Christianity between the fourth and seventh centuries, we may be puzzled that the controversies about the Trinity and about the person and natures of Jesus Christ were so heated, but there was a very good reason for that. The Arians who insisted that “The Son was made from nothing” might have revered God’s Son as the first and greatest of creatures, but a creature cannot save you. Only God can do that. Obviously, too, if you believe in a Trinitarian God, then the way you pray to such a Being will be very different from the way you would pray to a Unitarian God: the latter Being sounds more remote and less personal, so you won’t confide in it with your hopes, dreams and worries, as you would do if you believed you were talking to a community of persons. Finally, with regard to Jesus Christ, you cannot view Him as “one of us” if you believe His humanity was absorbed into His Divinity like a piece of burning iron is absorbed into the fire (as Monophysites and Coptic Christians do). Nor can you celebrate the Annunciation as the moment in history when God became man, if you believe that there was only a moral union between Christ’s Divinity and His humanity (as Nestorians do). In short: the theological controversies of the fourth to seventh centuries mattered, because they had powerful implications for the way in which people related to their God.

How new issues can trigger religious splits

Religions are dynamic entities, and they continually have to deal with new issues which their founders (or founding texts) didn’t explicitly address. It’s simply not possible to define a set of principles (be they credal or ethical) which can answer every new question that arises, because all statements are to some degree ambiguous. Take, for instance, the Christian affirmation that there are three Persons in one God. By itself, this statement cannot tell us whether we should think of God as having three Minds (one for each Person) or one Divine Mind, which each person realizes in His own unique way. We need a “living voice” to address questions like that. And as you can imagine, when new pronouncements are made – be they on the nature of God or the afterlife or how we should treat others – there is always the potential for a division of opinion, and a schism.

A further source of division: strategies for evangelization

So far we have talked about religious beliefs and injunctions as sources of potential divisions. But strategies for evangelization can prove to be sources of division as well. The best modern example of this phenomenon comes from the Soviet Union, whose dominant religion was that of Communism. (Communism, being a materialistic faith, could be described as an “earth religion,” but what makes it unusual was its linear view of time, and its promise of a bright and glorious future. As a rule, earth religions tend to be cyclic; Communion was a Utopian earth religion.) As readers of George Orwell’s Animal Farm will recall, the period of the 1920s was characterized by a brutal internal struggle between internationalists such as Leon Trotsky who wanted to advance the cause of Communism by fomenting revolutions abroad, and nationalists like Joseph Stalin, who advocated “socialism in one country.”

Religions, then, are inherently divisive for three reasons: their tenets and guiding principles are exquisitely sensitive to even minor changes in wording; their creeds and dogmas, by themselves, are incapable of resolving new questions, or matters where differing interpretations might arise; and their leaders may fiercely disagree on strategies for evangelization.

So how does the New Atheism stack up? Does it qualify as a religion?

Is New Atheism a religion?

Answering Gauguin’s “big questions”

|

There can be no doubt that New Atheism endeavors to answer the “big questions” of what we are, where we came from and where we are going. On the New Atheist account, everything we see around us, including ourselves, is the product of unguided processes, which can be described by mathematical equations (laws of Nature), acting on the matter and energy in our universe, whose original state can be modeled by a set of initial conditions. Books such as Alex Rosenberg’s The Atheist’s Guide to Reality: Enjoying Life without Illusions, Richard Dawkins’s The Magic of Reality: How We Know What’s Really True and Lawrence Krauss’s A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing are all examples of attempts by leading New Atheists (and fellow-travelers) to offer a coherent world-view that answers all of Gauguin’s “big questions.”

A straight and narrow path

In his book, The Moral Landscape, published in 2010, New Atheist Sam Harris contends that science can answer moral questions and that it can promote human well-being. According to Harris, the only rational moral framework is one where the term “morally good” means: whatever tends to increase the “well-being of conscious creatures.” Contrary to the widely accepted notion that you cannot derive an “ought” from an “is,” Harris maintains that science can determine human values, insofar as it can tell us which values are conducive to the flourishing of the human species. Harris’s approach to morality is a utilitarian one, which means that for him, the object of ultimate concern is the flourishing of the species as a whole. Indeed, he is famous for contending that it would be morally justifiable to push an innocent fat man into the path of an oncoming train, to prevent the train from running over five people further down the track. Harris’s book on morality has been highly praised by atheist luminaries such as Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker and Lawrence Krauss.

The prescriptions of most religions are explicitly ethical (e.g. “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and love your neighbor as yourself”), but they need not be: Buddhism, for instance, tells its followers to free themselves from craving by following the Eightfold Path, in order to avoid suffering. In the case of New Atheism, the underlying prescription is that you should embrace skepticism and use the scientific method, if you want to know anything at all about the world. The ethical principles are secondary: they arise from the application of this scientific principle to the study of human nature.

The potential for radically divergent conclusions arising from minor alterations to the religion’s tenets

As we saw, religions are distinguished by the interesting property that even minor variations in their founding principles (both factual and prescriptive) yield drastically different conclusions. When we examine New Atheism, we find that it possesses the same property, regardless of whether we look at its metaphysical statements about reality or its prescriptions about how we should think and act.

New Atheism is a materialistic world-view which denies the existence of libertarian free-will – a notion that its adherents regard as mystical mumbo jumbo. Mental states are said to supervene on underlying physical states: in other words, it is not possible that two individuals with the same physical arrangement of atoms in their bodies could have different mental states. The implicit assumption here is that there is no such thing as “top-down” causation within the material realm, and that causation is invariably “bottom-up.” But if higher-level holistic states of the brain and central nervous system can influence micro-states at the neuronal level, then it no longer follows that each of us is the product of our genes plus our environment. Again, New Atheists consider the universe to be a causally closed system. But if we allow the possibility of a multiverse, then it seems to me that we cannot guarantee causal closure. If we grant that a scientist in some other universe may have created our own universe, then how can we be sure that there has been no interaction between external intelligent agents and our universe, during its entire 13.8-billion-year history?

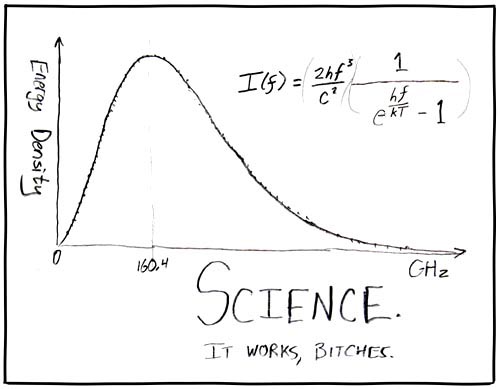

|

The “Science works” comic that was indirectly alluded to by Professor Richard Dawkins, in a talk at Oxford’s Sheldonian Theater on 15 February 2013. Image courtesy of xkcd comics. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License.

The New Atheist injunction that science is the only road to knowledge is no less fragile. The problem with this view, as I have pointed out previously, is that it leaves us with no way of justifying the scientific enterprise, which rests on a host of metaphysical assumptions about reality. (By the way, Richard Dawkins’s “Science works” is not an adequate justification, for it gives us absolutely no reason to believe that science will continue to work in the future. In other words, it fails to solve the problem of induction.) But if we allow even one of these metaphysical assumptions to stand alongside the foundational principles of science as a basis for knowledge, then we have violated our claim that all knowledge is based on science alone, and we can no longer call ourselves empiricists. What’s more, if there are some metaphysical truths that we are capable of knowing, then we have to provide some account of how we come to know these metaphysical truths. Are they intuitions which we “just know,” or do we infer them as presuppositions of science? We also have to confront the question: why should a mind which evolved for survival on the African savanna be capable of addressing metaphysical questions? (See also my article, Faith vs. Fact: Jerry Coyne’s flawed epistemology.)

When we look at the ethical principles of the New Atheism, we find still more fragility. Take Sam Harris’s assertion that we should strive to increase the “well-being of conscious creatures.” If we strive instead for the well-being of all self-conscious creatures, then sentient non-human animals won’t matter at all, and if we strive for the welfare of all living creatures, then even the humble bacterium will matter, and conceivably, the interests of bacteria (which are very numerous) could dwarf those of sentient animals (which comprise but a tiny twig on the tree of life). Again, is it creatures themselves which matter, or the species they belong to? What’s good for a species might turn out to be bad for the majority of individuals belonging to that species. And if it’s individuals that matter, then is it the greatest happiness of the greatest number of individuals that we should be trying to maximize, or are there certain kinds of harm which we should never allow even one individual to suffer? Supposing (as utilitarians do) that our duty is to maximize overall happiness, are we supposed to maximize the average happiness of all conscious individuals, or the total amount of happiness experienced by individuals? For instance, is a world with a few very happy individuals better or worse than a world with lots of slightly happy ones?

An epistemic theory of how we know the religion’s claims to be true

Any religion has to provide some sort of account as to how its factual and ethical claims can be known to be true, for the benefit of its adherents (who may be subject to doubts from time to time). Supernatural religions commonly cite evidence of miracles: for instance, the kuzari principle (which basically says that you can’t fool all of the people all of the time) is very popular with Jews (who use it to support their claim that God worked public miracles that were witnessed by all of the Israelites), and for their part, Christian apologists (such as Drs. Tim and Lydia McGrew) appeal to the strength of testimony by multiple eyewitnesses to build a cumulative case for the resurrection of Jesus. Hindus argue that the law of karma and the notion of reincarnation make more sense than the belief that we all go to Heaven or Hell when we die (see also here). Muslims are somewhat unusual in that they eschew appeals to miracles; instead, they argue that the Quran is self-authenticating because of its singular literary qualities.

When we look at less supernatural religions, such as Confucianism and Buddhism, we find that the method by which they justify their claims and injunctions is a pragmatic one. Thus Buddhists hold that anyone can verify the Four Noble Truths on the basis of their own personal experience, without having to go to some higher authority. Confucianism’s chief apologist (if you can call him that) was Mencius, who argued that human nature is inherently good, and that both experience and reason attest to the fact that we all have a built-in knowledge of good and evil, and of the will of Heaven.

New Atheism resembles these latter religions in that it appeals to pragmatic criteria, in order to back up its epistemic claims – the main difference being that New Atheists do not regard introspection as a valid source of knowledge (even self-knowledge), whereas Buddhists and Confucians do. The arguments for New Atheism can be summed up in five words: “Science works; nothing else does.” The distinctive claim of New Atheism, as a religion, is its cocksure assertion that the scientific method offers the only reliable way of knowing anything about our world, and that any claims which cannot be tested using this method can be regarded as nonsense. The scientific method assumes that we can perform (and replicate) experiments: for that to happen, we need entities that behave in accordance with scientific laws. Since there is no scientific way of verifying the existence of lawless entities, such as pixies or spirits, we can set them aside. Finally, we can apply the scientific method to human nature itself, and investigate what makes people tick and what is conducive to their flourishing, and to the flourishing of society in general. Indeed, we can do the same for all sentient beings. What New Atheism claims to offer its adherents, then, is a way of understanding our world and of answering any meaningful question that we can ask about it. In this respect, it functions very like a religion.

Unresolved epistemic issues

Many critics of New Atheism have argued that it is unable to justify its materialistic claim that the only things that exist are entities which are subject to physical laws of some sort, its bold epistemic claim that the scientific method offers us the only route to knowledge, and its ethical claim that we should strive to increase the well-being of conscious creatures. For the most part, New Atheists have responded by shifting the burden of proof: if there exists immaterial entities such as spirits, then the onus is on people who believe in them to supply proof (or at least, very strong evidence) of their existence; if there are non-scientific ways of knowing, then the onus is on people who defend these ways of knowing so explain how they work and we we should regard them as reliable; and if we have any other duties besides increasing the well-being of conscious creatures, then the onus is on people who claim that we have these additional duties to explain what they are and why we have them.

While this strategy of shifting the burden of proof has been a very effective tactic against other religious believers, it fails to address the arguments of those who are skeptical of skepticism itself. We are told that the only entities which are real are ones which obey physical laws, but we are not told what a physical law is, or what it means for something to obey a law, or why we should believe that these laws will continue to hold in the future. We are not told why the scientific way of knowing is reliable for all times and places – or even why it works for any time and place. Lastly, we are not told why we have any moral duties towards others. Indeed, Professor Jerry Coyne, who is himself a leading New Atheist, has criticized Sam Harris’s claim that we can deduce an “ought” from an “is” (see here and here). Unlike most New Atheists, Coyne holds that ethical norms arise from shared subjective preferences (which have been shaped by our evolutionary past): most of us happen to like living in a society which promotes people’s happiness and strives to reduce suffering, but there’s no objective reason why we should promote other people’s happiness or reduce their suffering.

In short: New Atheism faces a real epistemic crisis, which it has so far failed to confront. So why do its adherents seem so unperturbed by this crisis? The real reason, I would argue, is that it doesn’t have to address all these unresolved epistemic issues in order to secure adherents; all it has to do is out-perform its leading competitors in the market for ideas. So long as New Atheism can poke fun at Christians and Muslims and make their epistemic claims look foolish, then it will have accomplished its objective of looking like a better and more rational alternative. New Atheism faces no real competition from die-hard skeptics who claim that we cannot know anything, for the very simple reason that few people find such a philosophy attractive – and even if they did, nobody can live in accordance with such a world-view on a day-to-day basis.

Arguments about strategies for evangelization

|

At the present time, the key point of division within the New Atheist movement is: should New Atheism be a moral movement?

In recent years, the New Atheist movement has fragmented, largely because of the extremely crude sexist behavior of certain online atheists, which skeptical blogger and Skepchick founder Rebecca Watson (pictured above, courtesy of Wikipedia) first drew attention to in her December 2011 post, Reddit makes me hate atheists. In August 2012, after penning an explosive article titled, How I Unwittingly Infiltrated the Boy’s Club & Why It’s Time for a New Wave of Atheism, atheist blogger and scientist Jen McCreight launched a new movement called Atheism+, whose ideals she defined as follows:

We are…

Atheists plus we care about social justice,

Atheists plus we support women’s rights,

Atheists plus we protest racism,

Atheists plus we fight homophobia and transphobia,

Atheists plus we use critical thinking and skepticism

The feminist and atheist blogger Greta Christina lent her support to the fledgling movement, with her post, Atheism Plus: The New Wave of Atheism, and leading atheist Richard Carrier shortly afterwards followed suit, in his post, The New Atheism +.

Atheism Plus has turned out to be even more intolerant than the New Atheism from which it split off. One comment made by Carrier on his blog is chilling in its strident advocacy of publicly denouncing anyone who doesn’t toe the line and espouse the principles of Atheism Plus:

If you mean “rational people will be making mental notes of who is irrational, then documenting it, and publicly informing their colleagues of it,” then yes. There is no other way to promote a rational society than to call out those who are irrational and denounce and marginalize them as such. No longer will we treat them as one of us. Because they are not.

There won’t be any central committee for this. Just the internet and the evidence.

Accept it or GTFO.

But the real problem with Atheism Plus, as I see it, is that by adding certain ethical tenets to New Atheism, it implicitly concedes that the epistemic principles espoused by New Atheists (i.e. universal skepticism and the use of the scientific method to assess truth claims) are incapable, by themselves, of yielding those tenets. Such an admission constitutes a striking lack of confidence in New Atheism as a philosophy – for if it cannot tell us what is right and wrong, then it is ethically deficient.

Atheist blogger P.Z. Myers concedes as much in an August 2012 post titled, Following up on last night’s Atheism+ discussion, where he quotes from an article he previously wrote in Free Inquiry, titled, Atheism’s Third Wave:

Science is neutral on moral concerns; it only describes what is, now how it ought to be. And this is true; science is a tool that can be used equally well for curing diseases or building bombs. But scientists are not and should not be morally neutral, nor should scientific organizations or culture be excluded from defining the appropriate uses of science…

Similarly, atheism may be value-neutral, but atheists and atheist organizations should not be…

… Because I’m an atheist and share common cause with every other human being on the planet in desiring to live my one life with equal opportunity, I suggest that atheists ought to fight for equality for all, economic security for all, and universally available health and education services… Ours should be a movement that welcomes all sexes, races, ages, and abilities and encourages an appreciation of human richness. Atheism ought to be a progressive social movement in addition to being a philosophical and scientific position, because living in a godless universe means something to humanity.

Commenting on his article, Myers added:

And if you don’t agree with any of that — and this is the only ‘divisive’ part — then you’re an asshole. I suggest you form your own label, “Asshole Atheists” and own it, proudly. I promise not to resent it or cry about joining it.

Several points are apparent from the foregoing extract. First, there is indeed a major ethical rift between New Atheists and Atheists plus, over whether science can establish moral truths. Myers evidently regards science as value-neutral, while New Atheist Sam Harris is convinced that science can tell us what is right and wrong.

Second, Myers fails to address the metaphysical issue of who qualifies as a person. He claims to welcome people of all ages and abilities: well then, what about newborn babies who lack both language and self-consciousness, or for that matter, first-trimester fetuses, who are not yet sentient but whose bodies are running a genetic program which will enable them to develop into sentient and (ultimately) rational beings, when placed in a suitable environment (i.e. the womb)? There is a very good reason why Myers does not mention these issues in his blog post: as I pointed out four years ago in an article I wrote on Uncommon Descent, Myers doesn’t believe that newborn babies are persons, or that they are fully human. “I’ve had a few. They weren’t,” he writes.

Third, Myers’ goals seem unobjectionable… until you read the fine print. “Universally available health and education services” sounds lovely, but does that mean that health care and education ought to be free for everyone who cannot pay, regardless of cost? How far would Myers like the welfare state to extend? And how much would he tax the rich?

Fourth, even if you agree with Myers’ goals, you might reasonably disagree with the means he proposes for attaining them.

Fifth, it never seems to occur to Myers that inclusiveness might not always be a good thing, and that some forms of discrimination might be rational. Welcoming people of all races and sexes is one thing; welcoming people of all fetishes and paraphilias is quite another. Additionally, an honest skeptic would not prejudge the issue of whether homosexuality or transgenderism is normal, but would instead keep an open mind. Myers’ mind strikes me as firmly closed shut on these issues.

Advocates of Atheism plus also faced some flak from critics who asked why they didn’t simply call themselves humanists. In response, atheist blogger Ashley Miller penned a thoughtful reply titled, The difference between “atheism +” and humanism, in which she wrote:

The desire to hold on to “atheism” rather than use the term “humanism” isn’t from a fundamental difference of goals and beliefs, but from a difference of self-definition. I personally like “atheism +” because it’s more confrontational, embraces a minority position that is loathed by many, and it is more transparent about the belief that religion is one of the root causes of many social injustices. My humanism is more than just secular, it is anti-religion.

Meanwhile, there appears to be no sign of a rapprochement between the New Atheist Old Guard and the younger leaders of the Atheism Plus movement, many of whom think that the leading spokesmen for the New Atheist movement have outlived their usefulness. In a recent article in the Guardian, (Richard Dawkins has lost it: ignorant sexism gives atheists a bad name, September 18, 2014), journalist Adam Lee reported on the widespread disillusionment among atheists with Richard Dawkins, author of The God Delusion:

He may have convinced himself that he’s the Most Rational Man Alive, but if his goal is to persuade everyone else that atheism is a welcoming and attractive option, Richard Dawkins is doing a terrible job. Blogger and author Greta Christina told me, “I can’t tell you how many women, people of color, other marginalized people I’ve talked with who’ve told me, ‘I’m an atheist, but I don’t want anything to do with organized atheism if these guys are the leaders.’”

It’s not just women who are outraged by Dawkins these days: author and blogger PZ Myers told me, “At a time when our movement needs to expand its reach, it’s a tragedy that our most eminent spokesman has so enthusiastically expressed such a regressive attitude.”

Following the publication of Lee’s article, New Atheists sprang to Dawkins’s defense. Jerry Coyne swiftly responded in a post titled, Adam Lee has lost it:

…[L]et me say this: I am friends with both Richard [Dawkins] and Sam [Harris], have interacted with them a great deal, and have never heard a sexist word pass their lips. (You may discount that if you wish since I have a Y chromosome, but I speak the truth.) Both have seemed to me seriously concerned with women’s rights, particularly as they’re abrogated by religion, and both have written about that. But does that count? No, it’s all effaced by a few remarks that can be twisted into accusations of sexism and, yes, misogyny, which is “hatred of women.”

These men do not hate women, and their opponents are ideologues. Michael Nugent, head of Atheist Ireland and one of the most conciliatory atheists I know, has tried reaching out to those who denigrate Richard and Sam, asking for dialogue and requesting that the hounders behave like civilized human beings — as Nugent himself always has. No dice. For trying to be conciliatory, Nugent has been, and is being, vilified. It’s disgusting. I feel sorry for the man, who is learning the hard way that good intentions are not enough to stay a pack of baying hounds.

Reading these exchanges, I get the impression that the divide between New Atheists and members of Atheist Plus is no longer just about strategy or even about feminism; it’s widened into a debate about how we identify social wrongs that need to be righted.

A tendency to split into sects

Back in 2009, the New Atheist movement was still in its infancy. At that time, NPR reporter Barbara Bradley Haggerty wrote an online article titled, A Bitter Rift Divides Atheists, in which she cited the concerns of Center for Inquiry founder Paul Kurtz, that New Atheism would set the atheist movement back:

“I consider them atheist fundamentalists,” he says. “They’re anti-religious, and they’re mean-spirited, unfortunately. Now, they’re very good atheists and very dedicated people who do not believe in God. But you have this aggressive and militant phase of atheism, and that does more damage than good.”

He hopes this new approach will fizzle.

“Merely to critically attack religious beliefs is not sufficient. It leaves a vacuum. What are you for? We know what you’re against, but what do you want to defend?”

Six years have passed since then, and as we have seen, Kurtz’s question, “What are you for?” has now split the New Atheist movement itself down the middle, with the emergence of a vocal splinter group called Atheism plus.

However, it would be grossly simplistic to think that New Atheism is divided into only two factions, as Jack Vance points out in a 2013 post on his blog, Atheist Revolution:

You see, I reject the perspective that this rift represents an open conflict between two well-defined sides (i.e., the Freethought Blogs/Skepchick/Atheism+ side vs. the Slymepit side). I understand the appeal of simplifying this by pretending that there are only two sides and that these are those sides. It is very difficult to talk about a conflict involving more than two sides, and simplification is damned tempting. Unfortunately, this is a case where simplifying things to two sides does not reflect reality.

In the meantime, the rift between New Atheism and other atheists has, if anything, intensified. New Atheist Jerry Coyne recently authored a post titled, Why do many atheists hate the New Atheists? The title says it all, really. Coyne sums up his own gloomy thoughts on the subject:

The critique of New Atheists by other atheists seems to consist largely of ad hominem accusations, distortions of what they’ve said (Sam Harris is particularly subject to this), and, most of all, complaints that they dare criticize religion publicly…

Now I’m perfectly happy accepting that it’s not the style of some nonbelievers to openly declare their atheism, much less to publicly criticize religion. But why go after the ones who do, especially when they’re simply articulating the reasons why the non-vociferous atheists have rejected religion? …

These are just some tentative thoughts, but the rancor of atheist criticism about New Atheists repeatedly surprises and saddens me. And I don’t fully understand it.

Finally, back in January 2013, neurologist and skeptic Stephen Novella, who identifies as a scientific skeptic rather than a New Atheist, wrote a thoughtful and conciliatory post, in which he argued that skepticism is not defined by the positions it takes on various issues, but by the methods it uses to assess claims. Novella also offered some reflections on the tendency of the skeptical movement to fragment over time:

All movements have internal divisions, and these divisions grow as the movement grows. There is a natural tendency for movements to splinter over time into sub-groups based upon these divisions. I think that would be disastrous for us, given that we are still a relatively small movement with a monumental task before us, including highly motivated (and often well-funded) opponents who wish our failure.

The upshot of all this is that the atheist movement – and especially the New Atheist movement – is increasingly looking like a house divided. Sectarianism, which is a defining feature of religion, appears to apply equally to New Atheism.

Conclusion

|

There is a common saying: “If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.” We have seen that New Atheism bears a number of striking resemblances to religion, on seven points: it attempts to answer the “big questions”; it prescribes a straight and narrow path for its followers; minor alterations to its tenets yield radically divergent conclusions; it attempts to provide an answer as to how its adherents can know how that its claims to be true; it has unresolved epistemic issues relating to what we know and how we can know it; its leaders argue about strategies for evangelization; and it has a tendency to splinter into sects. In view of these many points of similarity, I think it is fair to conclude that New Atheism belongs in the same category as the creeds it criticizes. While it is definitely not a cult, it can legitimately be called a religion.

What do readers think?