Over at WEIT, Professor Jerry Coyne has put up three interesting posts during the past few days, with questions for his readers relating to free will, the irrationality of belief in Divine revelation, and climate skepticism. I’d like to briefly respond to his questions.

Free will

In a post titled, Once again with free will: a question for readers (August 16, 2016), Professor Coyne laments the persistence of popular belief in libertarian free will – the view that whenever I make a choice, I could have chosen otherwise, otherwise my choice would not be free. Professor Coyne contrasts this view (which he calls view A) with the hard determinist view (called view B), which he espouses. On this view, the libertarian understanding of free choice is correct, but free choice is an illusion: no matter how free we feel when we act, our brains are bound by the laws of physics, and our behavior is determined by either our genes or our environment, and by nothing else. There is a third opinion, called soft determinism (view C), whose proponents agree with hard determinists that our actions are determined (“with all molecules configured identically, we can do only a single thing,” as Professor Coyne puts it), but disagree with hard determinists about the meaning of freedom: on this view, determinism is compatible with some conception of free will (insofar as I still act rationally and willingly), but not with the libertarian contra-causal view of free will.

Professor Coyne considers the difference between views B and C to be “largely semantic,” and observes (correctly) that if determinism is true, then “[y]ou simply CANNOT freely accept whether or not to hold Christ as your savior, or Muhammad as Allah’s prophet.” He concludes by posing a question to his readers (my emphases):

Philosophers squabble about the difference between classes [or views – VJT] B and C, whereas to Professor Ceiling Cat (Emeritus) [that’s Jerry Coyne’s nickname for himself on his Website – VJT], a far more important argument is to be had between members of combined class (B + C) — the determinists — versus members of class A, the libertarians. To me, the latter argument, B + C vs. A, is of vital importance for making society better, while the argument between B vs. C is basically a semantic squabble that has an import on academic philosophy but not on society.

Do you agree with me or not? State your reasons. (Try to be briefer than I’ve been!)

I agree with Professor Coyne on this point: the debate between libertarians and determinists about whether we have the power to do otherwise (contra-causal free will) is an all-important one. But my reason has nothing to do with making society better, although that certainly matters. Rather, my reason has to do with making individual people better. To build a good society, you need good people. And in order for people to be good, they have to believe not only that they can change the world around them; they have to believe that they can change themselves – indeed, conquer themselves – in order to free themselves from the chains of vice and overcome their character weaknesses. Determinism discourages such a belief: someone who believes that they lack the power to do otherwise when they make a choice is more likely to shrug their shoulders when confronted with a temptation and think, “I am what I am, and I might as well not try to fight it.” Belief in determinism is massively demoralizing, whereas belief in libertarian free will is ennobling. It’s as simple as that.

And of course, if we have libertarian free will, then we can freely choose our philosophy of life, and our religion, too.

Is that brief enough for you, Professor Coyne?

Coyne’s “proof” that the Scriptures are entirely man-made

In another post titled, Proof that the scriptures are man-made and don’t convey God’s word (August 16, 2016), Professor Coyne relates the story of a brilliant argument against revealed religion, which occurred to him at 2 o’clock in the morning. He begins by quoting from a Wikipedia article on ethics in the Bible:

Elizabeth Anderson criticizes commands God gave to men in the Old Testament, such as: kill adulterers, homosexuals, and “people who work on the Sabbath” (Leviticus 20:10; Leviticus 20:13; Exodus 35:2, respectively); to commit ethnic cleansing (Exodus 34:11-14, Leviticus 26:7-9); commit genocide (Numbers 21: 2-3, Numbers 21:33–35, Deuteronomy 2:26–35, and Joshua 1–12); and other mass killings.

Coyne observes: “These days nobody feels obliged to carry out such commands.” He then asks: why not? Coyne then puts forward his fatal trilemma: either God didn’t really mean what he said (i.e. it’s all metaphor); or God did mean it, but times have changed; or God didn’t say it, and the Scriptures are entirely a product of human morality.

Coyne rejects the first option because the Biblical injunctions are presented in the context of “historical accounts” of what God commanded. He rejects the second option because it is tantamount to relativism: if God’s commands regarding slavery and homosexuality can change when the circumstances change, then anything goes. That leaves us with the third option: “the morality ‘dictated by God’ was really a reflection of a morality held by humans.”

Let me begin by pointing out that Coyne’s trilemma is flawed, because it fails to consider a fourth possibility (defended by Christian thinkers such as William Lane Craig and C. S. Lewis): that while much of the Bible comes from God, parts of it have been corrupted by human beings. This option might seem a redundant one, but it has the merit of being able to account for passages in Scripture that preach a transcendent morality: laws that mandate acts of charity to people in need; laws designed to ensure that needy individuals of low social status would be taken care of, rather than being left to die; laws that tell people to love foreigners “as yourself”; and laws that forbid even secret feelings of hatred towards other people. And I’m not talking about the New Testament here. I’m talking about Leviticus 19. Leviticus is about as Old Testament as you can get.

As I wrote in a previous post, five years ago:

From an evolutionary standpoint, such laws are very, very odd. What is striking about these laws is that they are written from the transcendent perspective of a Being who reads our innermost thoughts, who knows if we are harboring hatred in our hearts, who witnesses deceitful words and deeds, and who sees and avenges acts of injustice. At the end of every command, this Being announces His presence: “I am the Lord.”

The idea of a transcendent judge is a notion that goes beyond our human categories: it appeals to a standard of morality which is personal and at the same time larger than any human mind can conceive. It is an idea which is bound to cause headaches for an evolutionary biologist who holds that all human concepts can be explained within a naturalistic framework. Where did a community of social primates get the idea of a transcendent lawgiver from? The idea cannot be naturalized: nothing within Nature furnishes us with an adequate source for the concept of a Reality that lies beyond Nature.

Coyne might complain about the harsh penalties meted out by God in Leviticus 20 (which I have previously discussed here, but unless he can account for the transcendent morality in Leviticus 19, his naturalistic hypothesis lies in tatters.

Coyne appeals to Plato’s famous “Euthyphro argument” in an attempt to prove that we don’t need God in order to know what’s right and what’s wrong. However, all his argument establishes is the necessity of human reason, when attempting to distinguish right from wrong. What Coyne is arguing for, though, is the sufficiency of human reason: he believes that reason (coupled with our ingrained sense of empathy) is all we need to tell right from wrong. His argument therefore fails to prove the point he wants to make.

Coyne is not done yet, however: he thinks he has another decisive argument against Biblical inspiration, for he adds:

The priors [i.e. antecedent probabilities – VJT] for humans making up the Bible are surely higher than the priors for some Palestinian scribes channeling the word of a God who never left any evidence for His existence. (This is, of course, irrelevant to the issue of whether Jesus or Moses really existed as non-divine beings.)

First, it is ridiculous to say that there is no evidence for God’s existence. Even if there were no good evidence, the fact remains that poor evidence is still evidence. Second, there is in fact good eyewitness evidence for miracles, as I have argued here and here. Evidence for miracles is strong prima facie evidence for God. Third, if there is evidence for God’s existence, then appealing to prior or antecedent probabilities in order to argue against the inspiration of Scripture is irrelevant. We have to deal with the posterior probability that Scripture is (in whole or in part) inspired by God, in the light of the evidence we now have. That is what makes my fourth option a more reasonable one than the third option proposed by Professor Coyne in his trilemma above.

Climate change

In a third post titled, Brian Cox has a genius response to a climate-change hater!, Professor Coyne wrote about the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s “Q&A” show, which recently featured physicist Brian Cox on a panel which included an Australian Senator, Malcolm Roberts, who denies the reality of man-made climate change. Here’s a short excerpt from the show, courtesy of Youtube:

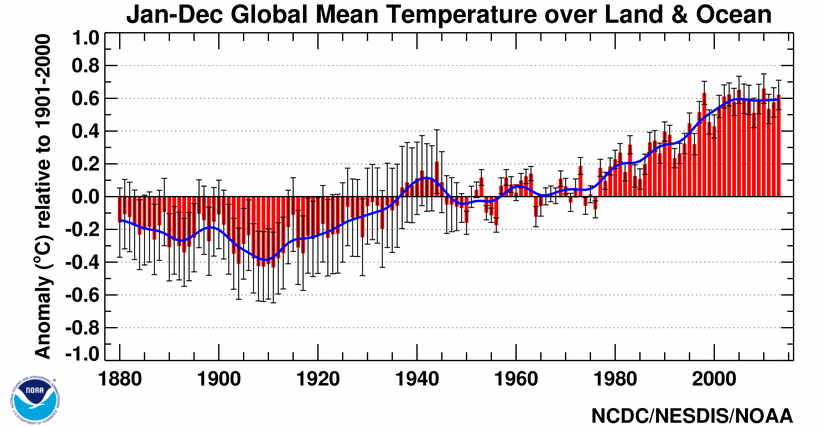

And here’s the graph used by Brian Cox during the show, which Malcolm Roberts derided as a NASA fake:

|

And here’s another graph which presents the temperature change data more clearly:

|

And here’s how it looks if you use a normal scale, with degrees Fahrenheit on the vertical axis (courtesy of Suyts space):

|

Not quite so alarming, is it?

I’d like to offer my own quick comments on the ABC show, and on the threat of global warming.

First, let me say up-front that anyone who thinks NASA has faked the climate change data is just silly. As Steve Mosher pointed out in a recent comment on Anthony Watts’ climate change blog, “NASA doesn’t adjust data.. they ingest NOAA data.” I might add that Senator Malcolm Roberts’ views are extreme and not at all typical of global warming skeptics: most of them readily acknowledge the reality of man-made global warming, but maintain that it is nowhere near as alarming as the IPCC predicts it will be. In other words, they’re lukewarmers, not “deniers.”

Second, Senator Malcolm Roberts appealed to the authority of Steve Goddard (whose real name is Tony Heller), who has been shown to be factually wrong on a number of issues.

Third, the 97% consensus figure has been severely critiqued on the Internet, for reasons which are summarized in a 2014 article on Popular Technology.net, titled, 97 Articles Refuting The “97% Consensus”. However, the latest research (see also here and here) appears to establish beyond reasonable doubt that 90 to 100% of climate experts do, in fact, agree that the global warming in recent years is man-made – although I should point out that the exact definition of “recent” varies from survey to survey. Additionally, the greater the level of climate expertise among the various kinds of scientists surveyed, the higher their level of agreement that global warming is indeed caused by human beings. So I think we can conclude that Brian Cox is right, regarding the existence of a scientific consensus on climate change.

Fourth, the consensus that Cox appeals to is a relatively modest one: most of the warming we have experienced in recent years (especially since the mid-20th century) is man-made. And that’s all. Currently, there’s no scientific consensus that global warming is likely to be catastrophic. And if it’s not going to be catastrophic, then Cox’s worries about the dangers of global warming are misplaced. While it’s reasonably certain that the rise in global temperatures since the late 1970s has been largely man-made, what’s not certain is how much temperatures will eventually rise in the future, as a result of further greenhouse gas emissions – in other words, the equilibrium climate sensitivity (or ECS), which is defined as the equilibrium change in global mean air temperatures near the Earth’s surface that would result from a sustained doubling of the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide. The scientific disagreement on this subject relates not to the effects of carbon dioxide but to the feedback effects of water vapor, which the IPCC claims will magnify the effects of carbon dioxide increases by a factor of two, three or four, or perhaps even six. The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) states that “there is high confidence that ECS is extremely unlikely [to be] less than 1°C and medium confidence that the ECS is likely between 1.5°C and 4.5°C and very unlikely [to be] greater than 6°C.” That’s quite a range of uncertainty.

Fifth, climate models have a bad track record of over-estimating the impact of man-made global warming, as this graph demonstrates. Thus Brian Cox’s alarmist claims that large areas of the Middle East will become uninhabitable as a result of global warming are decidedly premature: the claims relate to estimates for the year 2100, which are highly likely to be over-estimates.

Sixth, the cost of fighting global warming has been estimated by Professor Mark Jacobson at $100 trillion, which is higher than the entire world’s annual GDP, and 1,000 times more than the cost of the Apollo program, in today’s dollars. If you’re going to spend $100 trillion, common sense dictates that you should make sure you’re spending the money intelligently, and not investing it in any snake oil cures. Although the costs of solar and wind energy are falling, there’s a good reason for thinking that these renewable sources won’t be enough to solve the problem of global warming: as Professor John Morgan explains in an online article titled, The Catch-22 of Energy Storage, the ratio of energy returned on energy invested (EROEI) for solar and wind power plants is far too low for them to be viable as power sources in Western countries. In short: not only are current plans to fight global warming astronomically expensive, but they may not even work, anyway. Instead of rushing headlong into building more renewable energy power stations, we should be investing more money in research, which will probably save us money in the long run, and make the fight against global warming more affordable. In a recent interview, businessman Bill Gates has candidly acknowledged that it will take “clean-energy miracles” to solve the problem of global warming. “Today’s technologies,” he writes, “are a good start, but not good enough.” He argues that “we need a massive amount of innovation in research and development on clean energy.” Nevertheless, there are signs of hope: according to Gates, there are currently a dozen promising technology paths for clean sources of energy, and he believes that “in the next 15 years we have a high probability of achieving” energy which is “measurably less expensive than hydrocarbons, completely clean and providing the same reliability.” Gates also calls for more investment in next-generation nuclear power.

Finally, as I argued on a recent post, the fight against global warming, important as it is, must take second place to efforts to eradicate starvation, malnutrition and disease:

…[E]ven if the direst prognostications of the IPCC forecasters turn out to be correct, it would be morally wrong to withhold money from children who are dying now, in order to save generations of as-yet-unconceived children. Starvation, malnutrition and disease are clear and present dangers which kill millions. Future dangers can never take precedence over these crises. For this reason, I believe that citizens should actively resist proposals to spend tens of trillions of dollars fighting a long-term menace (global warming), at a time when children are dying of malnutrition.

Well, I think that three questions are quite enough for one day. What do readers think?