When we deal with deeply polarised topics such as ID, we face the problem of well-grounded reasoning vs fallacies. A fallacy being a significantly persuasive but fundamentally misleading argument, often as an error of reasoning. (Cf. a classic collection here.) However, too often, fallacies are deliberately used by clever rhetors to mislead the unwary. Likewise we face the challenge of how much warrant is needed for an argument to be credible.

All of these are logical challenges.

Let us note IEP, as just linked:

A fallacy is a kind of error in reasoning. The list of fallacies below contains 224 names of the most common fallacies, and it provides brief explanations and examples of each of them. Fallacies should not be persuasive, but they often are. Fallacies may be created unintentionally, or they may be created intentionally in order to deceive other people. The vast majority of the commonly identified fallacies involve arguments, although some involve explanations, or definitions, or other products of reasoning. Sometimes the term “fallacy” is used even more broadly to indicate any false belief or cause of a false belief. The list below includes some fallacies of these sorts, but most are fallacies that involve kinds of errors made while arguing informally in natural language.

An informal fallacy is fallacious because of both its form and its content. The formal fallacies are fallacious only because of their logical form. For example, the Slippery Slope Fallacy has the following form: Step 1 often leads to step 2. Step 2 often leads to step 3. Step 3 often leads to … until we reach an obviously unacceptable step, so step 1 is not acceptable. That form occurs in both good arguments and fallacious arguments. The quality of an argument of this form depends crucially on the probabilities. Notice that the probabilities involve the argument’s content, not merely its form.

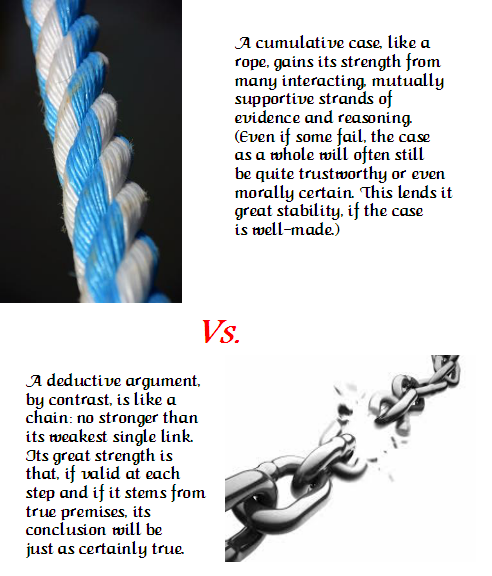

This focus on probabilistic aspects of informal fallacies brings out several aspects of the problem, for we often deal with empirical evidence and inductive reasoning rather than direct chained deductions. For deductive arguments, a chain is no stronger than the weak link, and if that link cannot be fixed, the whole argument fails to support the conclusion.

However, inductive arguments work on a different principle. Probability estimates, in a controversial context, will always be hotly contested. So, we must apply the rope principle: short, relatively weak individual fibres can be twisted together and then counter twisted as strands of a rope, giving a whole that is both long and strong.

For example, suppose that a given point has a 1% chance of being an error. Now, bring together ten mutually supportive points that sufficiently independently sustain the same conclusion. Odds that all ten are wrong in the same way are a lot lower. A simple calculation would be ([1 – 0.99]^10) ~10^-20. This is the basis of the classic observation that in the mouth of two or three independent witnesses, a word is established.

However, many will be inclined to set up a double-standard of warrant, an arbitrarily high one for conclusions they wish to reject vs a much softer one for those they are inclined to accept. Nowadays, this is often presented as “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

In fact, any claim simply requires adequate evidence.

Any demand for more than this cometh of evil.

This is of course the fallacy of selective hyperskepticism, a bane of discussions on ID topics. (The strength of will to reject can reach the level of dismissing logical-mathematical demonstration, often by finding some excuse to studiously ignore and side step as if it were not on the table.)

Of course, an objection will be: you are overly credulous. That is a claim, one that requires adequate warrant. Where, in fact, if one disbelieves what one should (per adequate warrant), that is as a rule because one also believes what one should not (per, lack of adequate warrant), which serves as a controlling belief. Where, if falsity is made the standard for accepting or rejecting claims, then the truth cannot ever be accepted, as it will run counter to the false.

All of this is seriously compounded by the tendency in a relativistic age to reduce truth to opinion, thence to personalise and polarise, often by implying fairly serious ad hominems. This can then be compounded by the “he hit back first” tactic.

This also raises the issue of the so-called concern troll. That is one who claims to support side A, but will always be found undermining it without adequate warrant, often using the tactics just noted. Such a persona in fact is enabling B by undermining A. This is a notorious agit prop tactic that works because it exploits passive aggressive behaviour patterns.

The answer to all of this is to understand how arguments work and how they fail to work, recognising the possibility of error and of participants who are in error (or are in worse than error) then focussing the merits of the case.

So, as we proceed, let us bear in mind the significance of adequate warrant, and the problem of selective hyperskepticism. END

PS: As it is relevant to the discussion that emerged, let me lay out the path to intellectual decay of our civilisation, adapting Schaeffer:

H’mm: Geostrategic picture:

As Scuzzaman highlights the slippery slope ratchet, let me put up the Overton Window (in the context of a ratchet that is steadily cranking it leftward on the usual political spectrum) — where, fallacies are used to create a Plato’s cave shadow-show world in which decision-making becomes ever more irrational, out of contact with reality:

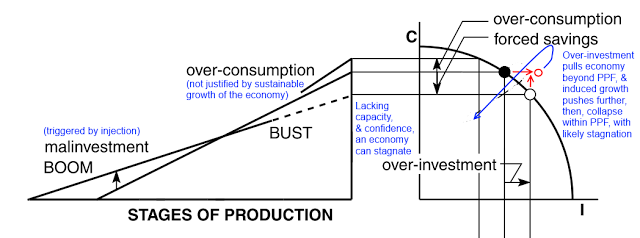

Likewise, here is a model of malinvestment-led, self-induced economic disaster due to foolishly tickling a dragon’s tail and pushing an economy into unsustainable territory, building on Hayek:

Let me add, a view of the alternative political dynamics and spectrum:

PPS: Mobius strip cut 1/2 way vs 1/3 way across vid: