From Quanta:

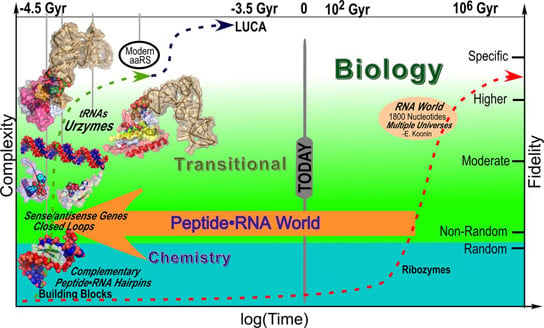

One of the most influential hypotheses states that it all began with RNA, a molecule that can both record genetic blueprints and trigger chemical reactions. The “RNA world” hypothesis comes in many forms, but the most traditional holds that life started with the formation of an RNA molecule capable of replicating itself. Its descendants evolved the ability to perform an array of tasks, such as making new compounds and storing energy. In time, complex life followed.

However, scientists have found it surprisingly challenging to create self-replicating RNA in the lab. Researchers have had some success, but the candidate molecules they have manufactured to date can only replicate certain sequences or a certain length of RNA. Moreover, these RNA molecules are themselves quite complicated, raising the question of how they might have formed through chance chemical means.

Nick Hud, a chemist at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and his collaborators are looking beyond biology to the role of chemistry in the development of life. Perhaps before biology arose, there was a preliminary stage of proto-life, in which chemical processes alone created a smorgasbord of RNAs or RNA-like molecules. “I think there were a lot of steps before you get to a self-replicating self-sustaining system,” Hud said.

Perhaps, but what was driving the “proto-life” to do anything at all, while the rest of non-life remained content in a non-living state?

Carl Woese, a renowned biologist who gave us the modern tree of life, believed that the Darwinian era was preceded by an early phase of life governed by very different evolutionary forces. Woese thought it would have been nearly impossible for an individual cell to spontaneously come up with everything it needed for life. So he envisioned a rich diversity of molecules engaged in a communal existence. Rather than competing with each other, primitive cells shared the molecular innovations they invented. Together, the pre-Darwinian pool created the components needed for complex life, priming the early Earth for the emergence of the magnificent menagerie we see today.

The ancient world called that the Golden Age of primal, peaceful simplicity. On that view, we now live in the Iron Age of competition and warfare.

Hud’s model takes Woese’s pre-Darwinian vision even further back in time, providing a chemical means for producing the molecular diversity that primitive cells needed.

One proto-life form might have developed a way to make the building blocks it needed to make more of itself, while another might have found a way to harvest energy. The model differs from the traditional RNA-world hypothesis in its reliance on chemical rather than biological evolution.

But this brings us back to, what motivated them to act the way they did?

Hud and his collaborators propose that RNA and proteins evolved in tandem, and those that figured out how to work together survived best. This idea lacks the simplicity of the RNA world, which posits a single molecule capable of both encoding information and catalyzing chemical reactions. But Hud suggests that facility might trump elegance in the emergence of life. “I think there’s been an overemphasis on what we call simplicity, that one polymer is simpler than two,” he said. “Maybe it’s easier to get certain reactions going if two polymers work together. Maybe it’s simpler for polymers to work together from the start.” More.

It’s only “simpler” for two polymers to work together if they intend to achieve a goal. Thus we can’t simply set aside the question of purpose or motivation, however we understand it. Which is what distinguishes life from non-life.

It’s all interesting and useful, but it doesnt shed light on the critical question.

See also: Welcome to “RNA world,” the five-star hotel of origin-of-life theories

What we know and don’t know about the origin of life

and

What can we learn about the drive to live?

Follow UD News at Twitter!