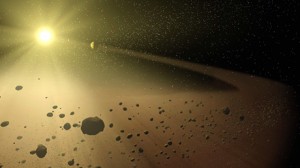

The most common explanation for the formation of planet Earth is that it formed by gravitational collapse from a cloud of particles (gas, ice, dust) swirling around the Sun. Specifically, the idea is that small planetesimals form as the various particles clump together (perhaps initially by cohesion, then by gravity), eventually growing into planets. Known as the “accretion hypothesis,” this is the standard model of planet formation, not just for Earth, but for nearly all planets.*

Courtesy, NOVA

Significant debate continues regarding the formation of the Moon, but the most widely-held hypothesis is that the Moon formed in a similar way via accretion of impact material produced by a violent collision between a Mars-sized object and the Earth.

For purposes of the current discussion, I want to set aside the debate about Moon formation for a moment and focus on the formation of a planet from a circumstellar disk.

Evidence for the Accretion Hypothesis

There is a decent amount of circumstantial evidence one can point to in support of the idea of planet formation via accretion from a circumstellar disk. The evidence is primarily two-fold:

First, a number of stars have been imaged with a circumstellar disk around them. These are thought to be solar systems in the early stages of formation, prior to the time when the planets would have cleared out the vast majority of the disk particles.

Second, we have witnessed live examples of meteors, comets and asteroids striking an object that is many orders of magnitude larger and “accreting” onto those much larger objects. For example, numerous meteors strike the Earth’s atmosphere on a daily basis, with the smaller bodies leaving behind dusty remnants and some larger bodies striking the Earth in more solid form as meteorites. There are also examples of comets and other small bodies colliding with other planets in our solar system – Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9’s impact with Jupiter in 1994 being perhaps the most well-known and heavily-studied example.

Why, then, do I refer to these pieces of evidence, strong as they may be, as “circumstantial”? Precisely because in these events we do not see planets forming. It may be true that these kinds of events eventually produce planets, but given the timescales involved, we have not, and indeed simply cannot say that we have ever, seen a planet form. Planet formation lies in a timeframe that is inaccessible to our instruments: either in the deep past for existing planets or in the far future for planets that might arise from the circumstellar dust disks we have imaged.

This does not mean that the accretion theory is wrong. Indeed, it has quite a lot going for it, as mentioned. But it does mean that in trying to reconstruct the origin of planets, including Earth, we are dealing with historical science, rather than lab science. Meaning that, rather than being able to conduct repeatable experiments in the lab, we are left to examine competing hypotheses to decide which hypothesis of past events best explains what we see in existence today.

In addition to the circumstantial evidence, there are many computer models that have been put together based on the accretion hypothesis. These can be very useful to the extent they accurately model the physical realities. Yet it is important to keep in mind that these models are not data, they are not evidence in the sense of actual observations. True, to the extent we believe the models accurately reflect physical realities these models can help us understand the processes in question. Perhaps they can even help confirm our suspicions or guide our thinking in a particular way. But we need to keep in mind that they are at least one step removed from actual hard evidence. (As an aside, and there are nuances and exceptions to this aside, we can generally acknowledge that to the extent a model is based upon a particular hypothesis, it might be useful in understanding how the hypothesis would play out, but it cannot be relied upon to demonstrate the truth of the hypothesis.)

So the accretion hypothesis of planet formation enjoys (i) a decent amount of circumstantial evidence, and (ii) support from some computer models.

Accreting Questions

I am not here to argue that the accretion hypothesis is wrong. It may be spot on. It may be precisely what happened to give rise to Earth and the other planets. Yet, there are some lingering doubts, some open questions. Nothing yet rising to the level of a cogent argument against the accretion hypothesis, mind you; just a hint of unease with the usual explanation.

Are the doubts and hints of unease foundational? Are they enough to warrant skepticism? Or perhaps it is simply the case that our exploration and understanding of space are tentative, that the overall story is tight and secure, that there are merely a few details to be filled in? I’m not sure. But perhaps a quote or two will give us a hint of some open questions.

NASA’s webpage about the Origin of the Earth and Moon indicates:

About 130 scientists met December 1-3, 1998, in Monterey, California, to share ideas about the formation and very early history of the Earth and Moon. Conference organizers constructed the program to allow time for participants to discuss crucial issues, leading to lively and spirited debate.

The existence of “lively and spirited debate” is interesting, particularly given the certainty with which some people cling to particular hypotheses. Granted, this quote seems to be focused primarily on the Moon’s origin, but not exclusively.

The later statement about stellar and planetary formation jumped out at me:

The cloud from which the Solar System formed was composed of gas and dust. Somehow in that dusty cloud, the Sun formed in the center and the planets formed around it.

Notice the word “somehow” that plays such a prominent role. The article goes on to propose what that “somehow” may have been, but already we are getting a sense that things are not quite pinned down and that the general explanation might be a bit simplistic.

Again, this is not an argument against the idea. But a careful student of the hypothesis might be forgiven for pausing and thinking, “Hmmm . . .”

Recent Asteroid Collision

What about more direct evidence for accretion? NASA’s Spitzer Telescope had the opportunity to witness what researchers believe was a collision of asteroids just a few months ago.

The press release is instructive, as it relates to the accretion hypothesis. A few quotes of note:

NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope has spotted an eruption of dust around a young star, possibly the result of a smashup between large asteroids. This type of collision can eventually lead to the formation of planets.

Notice the statement that a collision of two asteroids is the kind of collision that can “lead to the formation of planets.” Yet notice how one researcher describes what the evidence is actually showing:

We think two big asteroids crashed into each other, creating a huge cloud of grains the size of very fine sand, which are now smashing themselves into smithereens and slowly leaking away from the star . . .

Wait a minute. What that researcher is describing is most definitely not accretion. If anything it is dispersion.

Another researcher confirmed:

We not only witnessed what appears to be the wreckage of a huge smashup, but have been able to track how it is changing – the signal is fading as the cloud destroys itself by grinding its grains down so they escape from the star.

In contrast, a third researcher, apparently less interested in the actual evidence and more excited about the possible implications, gushed: “We are watching rocky planet formation happen right in front of us. This is a unique chance to study this process in near real-time.”

Sorry, no. What you saw was a collision between bodies that tore them apart, which was then followed by further collisions of the smaller bodies that broke them apart, followed by an ever-further dispersion of the resulting debris.

We might be forgiven for pointing out that the dispersion they witnessed is precisely what we see whenever we witness a collision . . . certainly a collision of bodies that have even close to a similar mass.

Imagine a decent-sized meteor striking an old satellite in orbit around the Earth. Do we expect accretion to take place? Of course not. Rather, we instead now have the risk of multiple smaller pieces of debris that have to be tracked — not clumping together like kids in front of a candy story window, but instead with each piece of debris now on its own independent trajectory. This is not a hypothetical. This is what in fact occurs and what we are spending hard-earned dollars to track.

More on point, if we start looking at related scenarios, the questions multiply. Scientists still debate how Saturn’s rings were formed, but one of the primary proposed scenarios involves the breakup of moons. NASA’s website for kids explains:

But scientists aren’t sure when or how Saturn’s rings formed. They think the rings might have something to do with Saturn’s many moons. Earth has only one moon. But Saturn has at least 60 moons orbiting it that we know about. Asteroids and meteoroids sometimes crash into these moons and break them into pieces. The rings could be made from these broken pieces of moons.

I don’t know about you, kids, but to me that doesn’t sound like accretion. Precisely the opposite.

Other scientists propose that the rings are left over from the early nebular material in the solar system, which better preserves the accretion idea, but presents challenges of its own with little resolution.

Conclusion

Conclusion? I don’t have one. Again, I am not presenting any strong argument in the above against the accretion theory of planet formation. What I am presenting are some questions – questions that immediately arise as soon as we start to look into the idea and thinking through about the details. Questions which remain unresolved after decades of study and research.

Let me know your thoughts. Is the accretion hypothesis sound? Do the processes we actually do see in action (cometary impacts, asteroid collisions, satellite debris, etc.) support the idea of accretion? Given a primordial circumstellar disk, how would the transition take place from (a) collisions that primarily result in breakup and dispersion, to (b) collisions that result in accretion?

—–

* I add here, to prevent anyone going down the wrong path, that I appreciate and respect the work that is done in the astronomical community, including in the area of exoplanet research. I find the effort to discover another Earth-like planet to be extremely interesting, exciting and worthwhile, and follow it closely. I do not share the views, apparently held by some on this site, that the search for Earth-like planets is a fool’s errand, that Earth as a habitable planet is alone in the cosmos, that other intelligent life does not exist, or that some religious-based apple cart will be upset by the discovery of other habitable planets or other intelligent beings.

This thread is not devoted to such issues. To the extent possible, please focus comments on the actual mechanics and physics of planetary formation as they relate to the accretion hypothesis.