What would count as evidence against common descent given that organisms share such strong similarities? Darwin for the sake of argument assumed that the Creator (presumably God) created life, but argued the data accorded better with universal common ancestry. Nelson contested that view in his keynote address by arguing that if the principle of continuity is violated, there is no need to assume common ancestry. That even if a pair of organisms are 90% similar, that 10% difference could be sufficient to falsify common ancestry if the gap in differences are sufficiently large to be bridged by mindless processes.

IF it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.

Charles Darwin

But orphans are exactly that sort of “complex organ”, hence Darwinism has been falsified on Darwin’s own terms.

There are ID proponents who accept common descent, but a large fraction of ID proponents accept special creation. Strictly speaking, rejection of common descent does not necessarily imply ID, but it does make ID more believable for most people…

So how much difference is needed to challenge common descent? Consider if you had 90% of the characters correct in a 5000 character cryptographic key, is it reasonable to assume chance processes will resolve the final 10%? It is probably very easy to make a biological organism 10% different from another in terms of destructive processes, but not so easy in terms of constructive process since new protein systems are like new login/password, lock-and-key systems.

Nelson’s keynote highlighted the problem of orphan genes and presented them as evidence against common descent. To understand more about the orphan gene problem, visit A new mechanism of evolution — POOF.

Nelson pointed out that it was hoped that more sequencing would find the missing ancestors of the orphan genes which had looked like they poofed into existence. It was hoped the appearance of a POOF in the history of life was an illusion resulting from our lack of data, and that we would eventually find missing links for the orphans. But that has not happened, the gaps only have gotten worse the more we learn, and the trend is that we will discover more orphans as we sequence more organisms. That means we will find even more missing links, and that argues against common descent of those orphans, and by way of extension common descent of the organisms.

Nelson pointed out Ventner, Woese, Doolittle and others are skeptical of the need of common descent in light of these developments.

We cannot expect to explain cellular evolution if we stay locked in the classical Darwinian mode of thinking…

The time has come for biology to go beyond the Doctrine of Common Descent.

Carl Woese

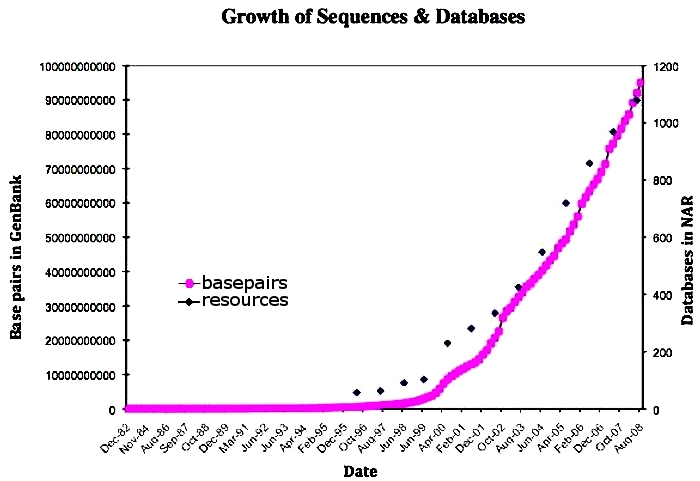

When Nelson made some of his bold claims about orphans, it was when the Genbank numbers were small in the 90s. That’s all changed. The best graph available goes to 2007, and it has since grown even more.

Nelson made a testable prediction that has been borne out by observation. Congratulations!

Nelson highlighted papers such as this one Orphans as taxonomically restricted and ecologically important genes.

This paper shows that a persistent pattern in biology of lots of species specific orphans will continue to be found in each organism, maybe 10% for one prospective data set:

A similar pattern can be seen for D1 where 10 % of all predicted coding regions in 200 species are predicted to be orphans.

How widespread will the pattern be as we sequence more organisms? Here is a problem:

These trends reveal several interesting points. First, given our current dataset for bacteria, it is not possible to make an estimate of the maximum number of orphans, as orphan growth does not show evidence of reaching a plateau. This conclusion is also supported by examining the rate at which new protein families are discovered (Kunin et al., 2003).

Second, it appears that improved taxonomic sampling of distantly related genomes is continuing to reveal large numbers of orphans. These data suggest that the number of bacterial orphan genes will continue to increase for the foreseeable future as long as we continue to assay novel branches of the microbial tree of life. Therefore, although improved taxonomic sampling is reducing the overall percentage of orphans, it cannot be used to assign all orphans to known gene families. Furthermore, it is also likely that orphans will continue to be found in lineages that have already been heavily sampled (Hayashi et al., 2001; Perna et al., 2001).

Creationist translation: more evidences against common ancestry will emerge. Orphans are important because if they have no ancestor, then arguments of slow gradual evolution of proteins from pre-existing proteins is falsified, and the numbers developed by Axe and Gauger become immune to complaints that they aren’t considering similarly functioning proteins since in the case of orphan proteins, similar pre-existing proteins do not exist. POOF becomes the only recourse.

In addition to the above study, here is another one:

Orphan genes are defined as genes that lack detectable similarity to genes in other species and therefore no clear signals of common descent (i.e., homology) can be inferred. Orphans are an enigmatic portion of the genome because their origin and function are mostly unknown and they typically make up 10% to 30% of all genes in a genome

http://gbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/5/2/439.abstract

Strictly speaking orphans don’t completely disprove common descent of entire creatures, but it does cast doubt on the common descent of orphans. But supposing 10-30% of genomes had to have been poofed into sudden existence, why not the whole organism? If POOF works as an explanation for 10-30%, why not 100%? That would seem more parsimonious if one accepts, as Darwin did for the sake of argument, that there is a Creator.

For sure there are deep similarities between humans and other creatures, but there are also differences. Evolutionists have made suspect claims of the degree of similarity (see: WD40 som fish are more closely related ot you than they are to tuna and ICC 2013 Jeff Tomkins vs evolutionary biologist who got laughed off stage).

The question then arises, supposing God is the Creator, despite some acute differences, why then did He did he also make creatures so similar? Subject of perhaps of another discussion. 😉

NOTES

1. Paul Nelson is one of the few YECs well-respected in both YEC and ID circles. He is the grandson of Byron C. Nelson a theology graduate of Princeton who argued against the damaging effects of Darwinism on society. Paul Nelson has compiled the writings of his grandfather here: The Creationist Writings of Byron C. Nelson

2. Three Byron C. Nelson awards were given at ICC 2013 to Steve Austin, John Baumgardner, and Russell Humphreys.

3. photo credits

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/core/assets/genbank/images/genbankgrowth.jpg