Nikolai Kondratiev was a Russian economist in the 1930’s who was shot by Stalin on September 17, 1938, because he had the integrity and courage to say the economic crisis of that decade, on statistical evidence, was largely a generation(s) length cyclical oscillation; not the Crisis of Capitalism leading to global Socialist Revolution that Marxist theory as understood by Stalin demanded. (Echoes in current debates on trends vs oscillations in climate trends etc are not coincidental. [Note, climate, technically, is a 30+ year moving average of weather.])

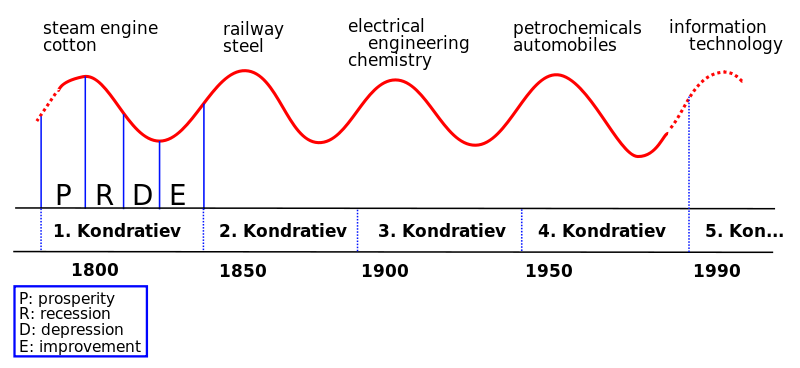

Joseph Schumpeter picked up his thought, and there has been a (somewhat marginalised/ “misunderestimated”) school of thinking on long waves across time.

One aspect of that, has been a focus on how key enabling technologies can drive the global economy . . . now, arguably struggling to break out of the ICT-1 trough and climb the ICT-2, AI & new energy etc led wave . . . arguably, held back by the missing investment in solar system colonisation-relevant tech since the 1970’s:

Arguably, this sort of pattern has played out over the past 1,000+ years, where on this count we are looking for K20 to rise with globe-transforming strength:

Analysing the driving dynamics, we can see how a relatively low level of pioneering investment across years or even decades plausibly enables the “next wave” . . . so, further arguably, we have been living off the Space Race since the 1970’s but may well have failed to adequately invest in the follow-on generation. So, we may be stuck in a low-growth patch of “looking for the next wave”:

Applying a cluster of strategic marketing models, we can then ponder the impact of a market for a product or technology that is sufficiently strong to dominate the global economy, reflecting a wave of adoption by investors and consumers alike:

Speaking of which, here is a Hayek Triangle of value-added driven view of a macro economy . . . economies gain strength when they lengthen the “tail” and invest in long term roots of production, which shifts balance to investment and accelerated growth:

Let me add a bit more on the Hayek, value-added Triangle:

However, tickling a dragon’s tail is a risky venture, and malinvestment led deep, persistent recession due to a shocked economy — aka, depression — is a serious issue.

I am of course arguing in the context of further global transformation and the future of our civilisation, with an eye to exorcising the ghost of Malthus.

In that light, I find the following from Richard Lipsey et al in Economic Transformations (OUP, 2005), “interesting”:

We start by observing that long-term growth is driven mainly by techno- logical change. This leads us to study the nature of technology and how it changes, building on material found in books such as Rosenberg’s Inside the Black Box. We argue that understanding technological change requires an evolutionary approach, such as was pioneered by Nelson and Winter in An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. We outline such an approach and contrast it with neoclassical theory. Because over the centuries new technologies radically alter more or less everything in the socio-economic order, doing much more than just increasing output per person, standard neoclassical theory is a relatively poor tool for studying their effects. We argue that one approach that handles these effects well is a combination of institutional and evolutionary economics that we call structuralist-evolutionary (S-E) theory . . . .

Big GPT [= General Purpose Technology] shocks change almost everything in a society and revitalize the growth process by creating an agenda for the creation of new products, new processes, and new organizational forms . . . .

We then discuss the nineteenth-century emergence of sustained growth of output in the West, building on the analyses in Rosenberg and Birdzell’s How the West Grew Rich and in Landes’ The Unbound Prometheus, but putting much more emphasis on science than is usual. This leads us to ask why sustained growth of output was not generated endogenously outside of the West, where we use much of the analysis found in Toby Huff’s The Rise of Early Modern Science, and take issue with some of the arguments in Kenneth Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence. Then we turn to the emergence of the West’s sustained per capita growth that happened later in the nineteenth century. This leads to a discussion of population dynamics . . .

Of particular relevance, here, is their observation that economic and population growth must be considered together, where growth in GDP per capita of 1 to 1.5% per annum is not perceptible in the short term as improvement in well-being (we add, as opposed to short-term consumption stimulus led booms with busts to follow), but in the longer term it transforms the prosperity of those in following generations who reap the benefits of the sacrifice and investment that opened up the opportunities. As Lipsey et al comment:

A third reason why the power of growth is often underassessed is because the growth of 1 or 1.5 per cent per annum changes per capita GDP so slowly that people barely notice its variations from year to year and hence do not regard variations in growth rates (over their normal range) as a big force in their lives. But anyone who was taken back 50 or 100 years[–> 170% to 340% increment in per capita income across 100 years, where of course we must further note that at say 1.5% growth per year of population, there would also be 4.4 times the population now being supported at the higher level, i.e. per capita growth is lower than gross growth in GDP once population is rising]

. . . would see the enormous power of such growth to alter living standards and to reduce the blight of poverty. [Lipsey et al, p. 9.]

For simple example, land used to plant solid timber trees

(I have mahogany in mind, a tree that given time can develop a trunk of 5 – 7 ft diameter, if reports of old growth Haitian trees from their mountains are true . . . I personally saw 5 – 6 ft diameter, 100 year old logs used as pilings then dug up as part of a road improvement project in Belize City in the 1980’s)

. . . could be used instead for short term cash crops instead but then in times to come we run out of good quality timber. That also holds for the temptation to over-harvest high quality old growth natural forests. That’s an almost simplistic example, but it makes a much bigger general point.

All of this is highly relevant to our current reflections on taking civilisation forward, exorcising the ghost of Malthus. END

PS: We started this series by looking at: metal winning through the FFC-Cambridge process, then looked more closely at Malthus vs energy technologies, as energy is a key driver. DV, next, on the idea of an open source driven industrial transformation relevant to solar system colonialisation. Recall, we need to be making 50-year investments in potential technology breakthroughs. All of the time.