Life forms strive to be more of what they are. Grains of sand don’t. You need more information to strive than to just exist.

Putting the idea of specified complexity to work, how do we measure meaningful information? What if an information-rich entity were scattered as molecules through the universe?

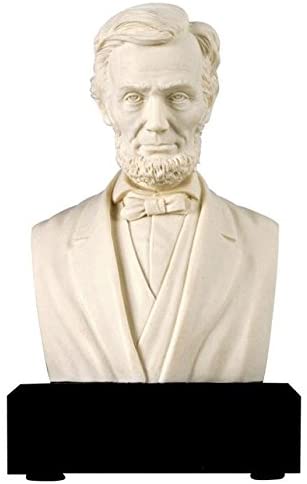

News, “How do we know Lincoln contained more information than his bust?” at Mind Matters News (November 11, 2021)

Michael Egnor: From the standpoint of information theory how does a bust of Lincoln, or statue of Lincoln, differ from Lincoln?

Robert J. Marks: Oh, well, I think they’re two different total worlds. For the bust of Lincoln we’re just only interested in the outside, the external surface. We’re not really interested in what goes on inside. I believe we’re constrained with whatever the physics of the 3D printer is …

Michael Egnor: I kind of like to take the observer out of it. Let’s not consider so much what we’re interested in, but rather, what the actual differences are.

Let’s say that you made the statue in such a way that it you also had a statue of Lincoln’s internal organs. You tried to make it as detailed as you could. How would the most detailed statue that you could imagine, differ from Lincoln himself, information theory-wise.

Robert J. Marks: Well, I think that in terms of meaning, Shannon information, Kolmogorov information, physical information… none of those address, meaning. The only way to address meaning of which I am aware in information theory is to place it into context. Into something which is meaningful. And that context must come through experience…

So in that sense, it is all based on context. I’m not sure, for example, how an alien — a bulbous blob sort of alien with no form — would look at the bust of Lincoln and think that it had any meaning. It would have to have the context of knowing what humans look like. And if it had no idea what humans looked like, it would just sit there and say: “This is just like a moon rock.”

Michael Egnor: As I mentioned in the past, I’m fascinated by the traditional Thomistic and scholastic definition of living things: they are things that strive to perfect themselves. And what Thomas Aquinas meant by that is that there are purposes built into nature, final causes — what he called teleology broadly. And those purposes provide goals for things in nature, that things in nature tend to change in the direction of those goals.

But what is unique about living things is that they act of their own accord to achieve their goals. Whereas nonliving things are acted upon, but don’t act of their own accord. An example would be: No matter how detailed a statue of Lincoln you make, the statue wouldn’t be trying to make itself a better statue of Lincoln.

Whereas Lincoln tried to make himself a better man every day. What made Lincoln alive was that he was always trying to be a better Lincoln. Better in terms of more fully realized or perfectly himself. As we all do, there’s always a striving in living things. And there’s no striving inanimate things. Statues don’t try to become better statues. They can only be made better by something external, but they don’t try it themselves.

Robert J. Marks: What you are describing, this intent to better yourself, is non-algorithmic. I would maintain that it is beyond the scope of naturalism, beyond the scope of information theory to capture, at least as I know it right now.

Takehome: Even bacteria, not intelligent in the sense we usually think of, strive. Grains of sand, the same size as bacteria, don’t. Life entails much more information.

Here are the previous episodes in the series:

- How information becomes everything, including life. Without the information that holds us together, we would just be dust floating around the room. As computer engineer Robert J. Marks explains, our DNA is fundamentally digital, not analog, in how it keeps us being what we are.

- Does creativity just mean Bigger Data? Or something else? Michael Egnor and Robert J. Marks look at claims that artificial intelligence can somehow be taught to be creative. The problem with getting AI to understand causation, as opposed to correlation, has led to many spurious correlations in data driven papers.

- Does Mt Rushmore contain no more information than Mt Fuji? That is, does intelligent intervention increase information? Is that intervention detectable by science methods? With 2 DVDs of the same storage capacity — one random noise and the other a film (BraveHeart, for example), how do we detect a difference?