(previous, here)

There has been a recent flurry of web commentary on design theory concepts linked to the concept of functionally specific, complex organisation and/or associated information (FSCO/I) introduced across the 1970’s into the 1980’s by Orgel and Wicken et al. (As is documented here.)

This flurry seems to be connected to the announcement of an upcoming book by Meyer — it looks like attempts are being made to dismiss it before it comes out, through what has recently been tagged, “noviews.” (Criticising, usually harshly, what one has not read, by way of a substitute for a genuine book review.)

It will help to focus for a moment on the just linked ENV article, in which ID thinker William Dembski responds to such critics, in part:

[L]et me respond, making clear why criticisms by Felsenstein, Shallit, et al. don’t hold water.

There are two ways to see this. One would be for me to review my work on complex specified information (CSI), show why the concept is in fact coherent despite the criticisms by Felsenstein and others, indicate how this concept has since been strengthened by being formulated as a precise information measure, argue yet again why it is a reliable indicator of intelligence, show why natural selection faces certain probabilistic hurdles that impose serious limits on its creative potential for actual biological systems (e.g., protein folds, as in the research of Douglas Axe [Link added]), justify the probability bounds and the Fisherian model of statistical rationality that I use for design inferences, show how CSI as a criterion for detecting design is conceptually equivalent to information in the dual senses of Shannon and Kolmogorov, and finally characterize conservation of information within a standard information-theoretic framework. Much of this I have done in a paper titled “Specification: The Pattern That Signifies Intelligence” (2005) [link added] and in the final chapters of The Design of Life (2008).

But let’s leave aside this direct response to Felsenstein (to which neither he nor Shallit ever replied). The fact is that conservation of information has since been reconceptualized and significantly expanded in its scope and power through my subsequent joint work with Baylor engineer Robert Marks. Conservation of information, in the form that Felsenstein is still dealing with, is taken from my 2002 book No Free Lunch . . . .

[W]hat is the difference between the earlier work on conservation of information and the later? The earlier work on conservation of information focused on particular events that matched particular patterns (specifications) and that could be assigned probabilities below certain cutoffs. Conservation of information in this sense was logically equivalent to the design detection apparatus that I had first laid out in my book The Design Inference(Cambridge, 1998).

In the newer approach to conservation of information, the focus is not on drawing design inferences but on understanding search in general and how information facilitates successful search. The focus is therefore not so much on individual probabilities as on probability distributions and how they change as searches incorporate information. My universal probability bound of 1 in 10^150 (a perennial sticking point for Shallit and Felsenstein) therefore becomes irrelevant in the new form of conservation of information whereas in the earlier it was essential because there a certain probability threshold had to be attained before conservation of information could be said to apply. The new form is more powerful and conceptually elegant. Rather than lead to a design inference, it shows that accounting for the information required for successful search leads to a regress that only intensifies as one backtracks. It therefore suggests an ultimate source of information, which it can reasonably be argued is a designer. I explain all this in a nontechnical way in an article I posted at ENV a few months back titled “Conservation of Information Made Simple” (go here).

A lot of this pivots on conservation of information and the idea of search in a space of possibilities, so let us also excerpt the second ENV article as well:

Conservation of information is a term with a short history. Biologist Peter Medawar used it in the 1980s to refer to mathematical and computational systems that are limited to producing logical consequences from a given set of axioms or starting points, and thus can create no novel information (everything in the consequences is already implicit in the starting points). His use of the term is the first that I know, though the idea he captured with it is much older. Note that he called it the “Law of Conservation of Information” (see his The Limits of Science, 1984).

Computer scientist Tom English, in a 1996 paper, also used the term conservation of information, though synonymously with the then recently proved results by Wolpert and Macready about No Free Lunch (NFL). In English’s version of NFL, “the information an optimizer gains about unobserved values is ultimately due to its prior information of value distributions.” As with Medawar’s form of conservation of information, information for English is not created from scratch but rather redistributed from existing sources.

Conservation of information, as the idea is being developed and gaining currency in the intelligent design community, is principally the work of Bob Marks and myself, along with several of Bob’s students at Baylor (see the publications page at www.evoinfo.org). Conservation of information, as we use the term, applies to search. Now search may seem like a fairly restricted topic. Unlike conservation of energy, which applies at all scales and dimensions of the universe, conservation of information, in focusing on search, may seem to have only limited physical significance. But in fact, conservation of information is deeply embedded in the fabric of nature, and the term does not misrepresent its own importance . . . .

Humans search for keys, and humans search for uncharted lands. But, as it turns out, nature is also quite capable of search. Go to Google and search on the term “evolutionary search,” and you’ll get quite a few hits. Evolution, according to some theoretical biologists, such as Stuart Kauffman, may properly be conceived as a search (see his book Investigations). Kauffman is not an ID guy, so there’s no human or human-like intelligence behind evolutionary search as far as he’s concerned. Nonetheless, for Kauffman, nature, in powering the evolutionary process, is engaged in a search through biological configuration space, searching for and finding ever-increasing orders of biological complexity and diversity . . . .

Evolutionary search is not confined to biology but also takes place inside computers. The field of evolutionary computing (which includes genetic algorithms) falls broadly under that area of mathematics known as operations research, whose principal focus is mathematical optimization. Mathematical optimization is about finding solutions to problems where the solutions admit varying and measurable degrees of goodness (optimality). Evolutionary computing fits this mold, seeking items in a search space that achieve a certain level of fitness. These are the optimal solutions. (By the way, the irony of doing a Google “search” on the target phrase “evolutionary search,” described in the previous paragraph, did not escape me. Google’s entire business is predicated on performing optimal searches, where optimality is gauged in terms of the link structure of the web. We live in an age of search!)

If the possibilities connected with search now seem greater to you than they have in the past, extending beyond humans to computers and biology in general, they may still seem limited in that physics appears to know nothing of search. But is this true? The physical world is life-permitting — its structure and laws allow (though they are far from necessitating) the existence of not just cellular life but also intelligent multicellular life. For the physical world to be life-permitting in this way, its laws and fundamental constants need to be configured in very precise ways. Moreover, it seems far from mandatory that those laws and constants had to take the precise form that they do. The universe itself, therefore, can be viewed as the solution to the problem of making life possible. But problem solving itself is a form of search, namely, finding the solution (among a range of candidates) to the problem . . . .

The fine-tuning of nature’s laws and constants that permits life to exist at all is not like this. It is a remarkable pattern and may properly be regarded as the solution to a search problem as well as a fundamental feature of nature, or what philosophers would call a natural kind, and not merely a human construct. Whether an intelligence is responsible for the success of this search is a separate question. The standard materialist line in response to such cosmological fine-tuning is to invoke multiple universes and view the success of this search as a selection effect: most searches ended without a life-permitting universe, but we happened to get lucky and live in a universe hospitable to life.

In any case, it’s possible to characterize search in a way that leaves the role of teleology and intelligence open without either presupposing them or deciding against them in advance. Mathematically speaking, search always occurs against a backdrop of possibilities (the search space), with the search being for a subset within this backdrop of possibilities (known as the target). Success and failure of search are then characterized in terms of a probability distribution over this backdrop of possibilities, the probability of success increasing to the degree that the probability of locating the target increases . . . .

[T]he important issue, from a scientific vantage, is not how the search ended but the probability distribution under which the search was conducted.

So, we see the issue of search in a space of possibilities can be pivotal for looking at a fairly broad range of subjects, bridging from the world of Easter egg hunts, to that of computing to the world of life forms, and onwards to the evident fine tuning of the observed cosmos and its potential invitation of a cosmological design inference.

That’s a pretty wide swath of issues.

However, the pivot of current debates is on the design theory controversy linked to the world of life. Accordingly Dembski focuses there, and it is worth pausing for a further clip so that we can see his logic (and not the too often irresponsible caricatures of it that so often are frequently used to swarm down what he has had to say):

[I]nformation is usually characterized as the negative logarithm to the base two of a probability (or some logarithmic average of probabilities, often referred to as entropy). This has the effect of transforming probabilities into bits and of allowing them to be added (like money) rather than multiplied (like probabilities). Thus, a probability of one-eighths, which corresponds to tossing three heads in a row with a fair coin, corresponds to three bits, which is the negative logarithm to the base two of one-eighths.

Such a logarithmic transformation of probabilities is useful in communication theory, where what gets moved across communication channels is bits rather than probabilities and the drain on bandwidth is determined additively in terms of number of bits. Yet, for the purposes of this “Made Simple” paper, we can characterize information, as it relates to search, solely in terms of probabilities, also cashing out conservation of information purely probabilistically.

Probabilities, treated as information used to facilitate search, can be thought of in financial terms as a cost — an information cost. Think of it this way. Suppose there’s some event you want to have happen. If it’s certain to happen (i.e., has probability 1), then you own that event — it costs you nothing to make it happen. But suppose instead its probability of occurring is less than 1, let’s say some probability p. This probability then measures a cost to you of making the event happen. The more improbable the event (i.e., the smaller p), the greater the cost. Sometimes you can’t increase the probability of making the event occur all the way to 1, which would make it certain. Instead, you may have to settle for increasing the probability to q where q is less than 1 but greater than p. That increase, however, must also be paid for . . . . [However,] just as increasing your chances of winning a lottery by buying more tickets offers no real gain (it is not a long-term strategy for increasing the money in your pocket), so conservation of information says that increasing the probability of successful search requires additional informational resources that, once the cost of locating them is factored in, do nothing to make the original search easier . . . .

Conservation of information says that . . . when we try to increase the probability of success of a search . . . instead of becoming easier, [the search] remains as difficult as before or may even . . . become more difficult once additional underlying information costs, associated with improving the search and [which are] often hidden . . . are factored in . . . .

The reason it’s called “conservation” of information is that the best we can do is break even, rendering the search no more difficult than before. In that case, information is actually conserved. Yet often, as in this example, we may actually do worse by trying to improve the probability of a successful search. Thus, we may introduce an alternative search that seems to improve on the original search but that, once the costs of obtaining this search are themselves factored in, in fact exacerbate the original search problem.

So, where does all of this leave us?

A useful way is to do an imaginary exchange based on many real exchanges of comments in and around UD, here by clipping a recent addition to the IOSE Intro-Summary (which is also structured to capture an unfortunate attitude that is too common in exchanges on this subject):

__________

>>Q1: How then do search algorithms — such as genetic ones — so often succeed?

A1: Generally, by intelligently directed injection of active information. That is, information that enables searching guided by an understanding of the search space or the general or specific location of a target. (Also, cf. here. A so-called fitness function which more or less smoothly and reliably points uphill to superior performance, mapped unto a configuration space, implies just such guiding information and allows warmer/colder signals to guide hill-climbing. This or the equivalent, appears in many guises in the field of so-called evolutionary computing. As a rule of thumb, if you see a “blind” search that seemingly delivers an informational free lunch, look for an inadvertent or overlooked injection of active information. [[Cf. here, here.& here.]) In a simple example, the children’s party game, “treasure hunt,” would be next to impossible without a guidance, warmer/colder . . . hot . . . red hot. (Something that gives some sort of warmer/colder message on receiving a query, is an oracle.) The effect of such sets of successive warmer/colder oracular messages or similar devices, is to dramatically reduce the scope of search in a space of possibilities. Intelligently guided, constrained search, in short, can be quite effective. But this is designed, insight guided search, not blind search. From such, we can actually quantify the amount of active information injected, by comparing the reduction in degree of difficulty relative to a truly blind random search as a yardstick. And, we will see the remaining importance of the universal or solar system level probability or plausibility bound [[cf. Dembski and Abel, also discussion at ENV] which in this course will for practical purposes be 500 – 1,000 bits of information — as we saw above, i.e. these give us thresholds where the search is hard enough that design is a more reasonable approach or explanation. Of course, we need not do so explicitly, we may just look at the amount of active information involved.

Q2: But, once we have a fitness function, all that is needed is to start anywhere and then proceed up the slope of the hill to a peak, no need to consider all of those outlying possibilities all over the place. So, you are making a mountain out of a mole-hill: why all the fuss and feathers over “active information,” “oracles” and “guided, constrained search”?

A2: Fitness functions, of course, are a means of guided search, by providing an oracle that points — generally — uphill. In addition, they are exactly an example of constrained search: there is function present everywhere in the zone of interest, and it follows a generally well-behaved uphill-pointing pattern. In short, from the start you are constraining the search to an island of function, T, in which neighbouring or nearby locations: Ei, Ej, Ek, etc . . . — which can be chosen by tossing out a ring of “nearby” random tries — are apt to go uphill, or get you to another local slope pointing uphill. Also, if you are on the shoreline of function, tosses that have no function will eliminate themselves by being obviously downhill; which means it is going to be hard to island hop from one fairly isolated zone of function to the next. In short, a theory that may explain micro-evolutionary change within an island or cluster of nearby islands, is not simply to be extrapolated to one that needs to account for major differences that have to bridge large differences in configuration and function. This is not going to be materially different if the islands of function and their slopes and peaks of function grow or shrink a bit across time or even move bodily like glorified sand pile barrier islands are wont to, so long as such island of function drifting is gradual. Catastrophic disappearance of such islands, of course, would reflect something like a mass extinction event due to an asteroid impact or the like. Mass extinctions simply do not create new functional body plans, they sweep the life forms exhibiting existing body plans away, wiping the table almost wholly clean, if we are to believe the reports. Where also, the observable islands of function effect starts at the level of the many isolated protein families, that are estimated to be as 1 in 10^64 to 1 in 10^77 or so of the space of Amino Acid sequences. As ID researcher Douglas Axe noted in a 2004 technical paper: “one in 10^64 signature-consistent sequences forms a working domain . . . the overall prevalence of sequences performing a specific function by any domain-sized fold may be as low as 1 in 10^77, adding to the body of evidence that functional folds require highly extraordinary sequences.” So, what has to be reckoned with, is that in general for a sufficiently complex situation to be relevant to FSCO/I [[500 – 1,000 or more structured yes/no questions, to specify configurations, En . . . ], the configuration space of possibilities, W, is as a rule dominated by seas of non-functional gibberish configurations, so that the envisioned easy climb up Mt Improbable is dominated by the prior problem of finding a shoreline of Island Improbable.

Q3: Nonsense! The Tree of Life diagram we all saw in our Biology classes proves that there is a smooth path from the last universal common ancestor [LUCA] to the different body plans and forms, from microbes to Mozart. Where did you get such nonsense from?

A3: Indeed, the tree of life was the only diagram in Darwin’s Origin of Species. However, it should be noted that it was a speculative diagram, not one based on a well-documented, observed pattern of gradual, incremental improvements. He hoped that in future decades, investigations of fossils over the world would flesh it out, and that is indeed the impression given in too many Biology textbooks and popular headlines about found “missing links.” But, in fact, the typical tree of life imagery:

. . . is too often presented in a misleading way. First, notice the skipping over of the basic problem that without a root, neither trunks nor branches and twigs are possible. And, getting to a first, self-replicating unicellular life form — the first universal common ancestor, FUCA — that uses proteins, DNA, etc through the undirected physics and chemistry of Darwin’s warm little electrified pond full of a prebiotic soup or the like, continues to be a major and unsolved problem for evolutionary materialist theorising. Similarly, once we reckon with claims about “convergent evolution” of eyes, flight, whale/bat echolocation “sonar” systems, etc. etc., we begin to see that “everything branches, save when it doesn’t.” Indeed, we have to reckon with a case where on examining the genome of a kangaroo (the tammar wallaby), it was discovered that “In fact there are great chunks of the [[human] genome sitting right there in the kangaroo genome.” The kangaroos are marsupials, not placental mammals, and the fork between the two is held to be 150 million years old. So, Carl Wieland of Creation Ministries incorporated, was fully in his rights to say: “unlike chimps, kangaroos are not supposed to be our ‘close relatives’ . . . . Evolutionists have long proclaimed that apes and people share a high percentage of DNA. Hence their surprise at these findings that ‘Skippy’ has a genetic makeup similar to ours.” Next, so soon as one looks at molecular similarities — technically, homologies (and yes, this is an argument from similarity, i.e analogy in the end) — instead of those of gross anatomy, we run into many, mutually conflicting “trees.” Being allegedly 95 – 98+% Chimp in genetics is one thing, being what, ~ 80% kangaroo or ~ 50% banana or the like, is quite another. That is, we need to look seriously at the obvious alternative from the world of software design: code reuse and adaptation from a software library for the genome. Worse, in fact the consistent record from the field (which is now “almost unmanageably rich” with over 250,000 fossil species, millions of specimens in museums and billions in the known fossil beds), is that we do NOT observe any dominant pattern of origin of body plans by smooth incremental variations of successive fossils. Instead, as Steven Jay Gould famously observed, there are systematic gaps, right from the major categories on down. Indeed, if one looks carefully at the tree illustration above, one will see where the example life forms are: on twigs at the end of branches, not the trunk or where the main branches start. No prizes for guessing why. That is why we should carefully note the following remark made in 2006 by W. Ford Doolittle and Eric Bapteste:

Q4: But, the evidence shows that natural selection is a capable designer and can create specified complexity. Isn’t that what Wicken said to begin with in 1979 when he said that “Organization, then, is functional complexity and carries information. It is non-random by design or by selection, rather than by the a priori necessity of crystallographic ‘order’ . . .”?

A4: We need to be clear about what natural selection is and does. First, you need a reproducing population, which has inheritable chance variations [[ICV], and some sort of pressure on it from the environment, leading to gradual changes in the populations because of differences in reproductive success [[DRS] . . . i.e. natural selection [[NS] . . . among varieties; achieving descent with modification [[DWM]. Thus, different varieties will have different degrees of success in reproduction: ICV + DRS/NS –> DWM. However, there is a subtlety: while there is a tendency to summarise this process as “natural selection, “this is not accurate. For the NS component actually does not actually ADD anything, it is a short hand way of saying that less “favoured” varieties (Darwin spoke in terms of “races”) die off, leaving no descendants. “Selection” is not the real candidate designer. What is being appealed to is that chance variations create new varieties. So, this is the actual supposed source of innovation — the real candidate designer, not the dying off part. That puts us right back at the problem of finding the shoreline of Island Improbable, by crossing a “sea of non-functional configurations” in which — as there is no function, there is no basis to choose from. So, we cannot simply extrapolate a theory that may relate to incremental changes within an island of function, to the wider situation of origin of functions. Macroevolution is not simply accumulated micro evolution, not in a world of complex, configuration-specific function. (NB: The suggested “edge” of evolution by such mechanisms is often held to be about the level of a taxonomic family, like the cats or the dogs and wolves.)

Q5: The notion of “islands of function” is Creationist nonsense, and so is that of “active information.” Why are you trying to inject religion and “God of the gaps” into science?

A5: Unfortunately, this is not a caricature: there is an unfortunate tendency of Darwinist objectors to design theory to appeal to prejudice against theistic worldviews, and to suggest questionable motives, that are used to cloud issues and poison or polarise discussion. But, I am sure that if I were to point out that such Darwinists often have their own anti-theistic ideological agendas and have sought to question-beggingly redefine science as in effect applied atheism or the like, that would often be regarded as out of place. Let us instead stick to the actual merits. Such as, that since intelligent designers are an observed fact of life, to explain that design is a credible or best causal explanation in light of tested reliable signs that are characteristic of design, such as FSCO/I, is not an appeal to gaps. Similarly, to point to ART-ifical causes that leave characteristic traces by contrast with those of chance and/or mechanical necessity, is not to appeal to “the supernatural,” but to the action of intelligence on signs that are tested and found to reliably point to it. Nor, is design theory to be equated to Creationism, which can be seen as an attempt to interpret origins evidence in light of what are viewed as accurate record of the Creator. The design inference works back from inductive study of signs of chance, necessity and art, to cases where we did not observe the deep past, but see traces that are closely similar to what we know that the only adequate, observed cause is design. So also, once we see that complex function dependent on many parts that have to be properly arranged and coupled together, sharply constrains the set of functional as opposed to non-functional configurations, the image of “islands of function” is not an unreasonable way to describe the challenge. Where also, we can summarise a specification as a structured list of YES/NO questions that give us a sufficient description of the working configuration. Which in turn gives us a way to understand Kolmogorov-Chaitin complexity or descriptive complexity of a bit-string x, in simple terms: “the length of the shortest program that computes x and halts.” This can be turned into a description of zones of interest T that are specified in large spaces of possible configurations, W. If there is a “simple” and relatively short description, D, that allows us to specify T without in effect needing to list and state the configs that are in T, E1, E2, . . En, then T is specific. Where also, if T is such that D describes a configuration-dependent function, T is functionally specific, e.g. strings of ASCII characters in this page form English sentences, and address the theme of origins science in light of intelligent design issues. In the — huge! — space of possible ASCII strings of comparable length to this page (or even this paragraph), such clusters of sentences are a vanishingly minute fraction relative to the bulk that will be gibberish. So also, in a world where we often use maps or follow warmer/colder cues to find targets, and where if we were to blindly select a search procedure and match it at random to a space of possibilities, we would be at least as likely to worsen as to improve odds of success relative to a simple blind at-random search of the original space of possibilities, active information that gives us an enhanced chance of success in getting to an island of function is in fact a viable concept.>>

__________

So, it seems that in the defined sense, conservation of information, search, active information, Kolmogorov complexity speaking to narrow zones of specific function T in wide config spaces W, the viability of these concepts in the face of drift, etc. are coherent, relevant to the scientific phenomena under study, and important. Where, the pivotal challenge is that for complex, functionally specific organisation and associated or implied information, there is but one empirically — and routinely — known source: intelligence. Let us see if further discussion of same will now proceed on reasonable terms. END

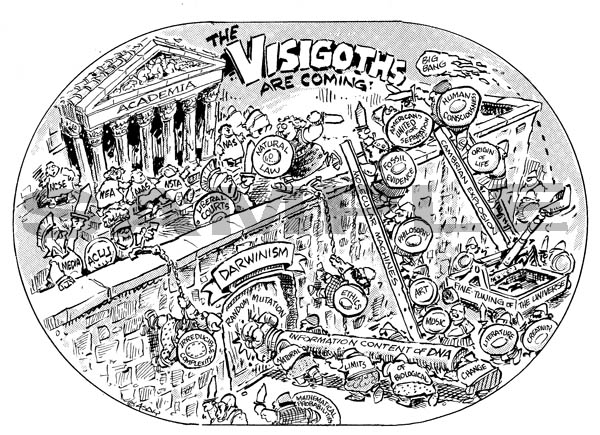

PS: Since we are going to pause and markup JoeF’s article JoeG makes reference to in comment no 1, let me give a free plug to the ARN tee shirt (and calendar and prints), highlighting the artwork, under the doctrine of fair use (as it has become material to an exchange):

The ad blurb in part reads:

A recent book attacking intelligent design (Intelligent Thought: Science vs. the Intelligent Design Movement, ed. John Brockman, Vintage Press, May 2006), , has chapters by most of the big names in evolutionary thought: Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins, Jerry Coyne, Steven Pinker, Lee Smolin, Stuart A. Kauffman and others. In the introduction Brockman summarizes the situation from his perspective: materialistic Darwinism is the only scientific approach to origins, and the “bizarre” claims of “fundamentalists” with “beliefs consistent with those of the Middle Ages” must be opposed. “The Visigoths are at the gates” of science, chanting that schools must teach the controversy, “when in actuality there is no debate, no controversy.”

While Brockman intended the “Visigoths” reference as an insult equating those who do not embrace materialistic Darwinism to uneducated barbarians, he has actually created an interesting analogy of the situation, and perhaps a prophetic look at the future. For it was the Visigoths of the 3rd and 4th centuries that were waiting at the gates of the Roman Empire when it collapsed under its own weight. For years the Darwinists in power have pretended all is well in the land of random mutation and natural selection and that intelligent design should be ignored. With this book (and several others like it), they are attempting to both laugh and fight back at the ID movement. Mahatma Gandhi summarized the situation well with his quote about the passive resistive movement: “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.”

Worth thinking about.