In recent exchanges, design objector RH7, has made objections to the concept of cause, regarding it as an outmoded, deterministic and classical (in the bad sense) view.

Since this is now clearly yet another line of objection to design inference on detection of credible causal factors, we need to add a response to this to the cluster of ID Foundations posts here at UD.

A useful way to do so is to highlight an ongoing exchange, here on, in the Universe Portal thread:

JDFL: 20th century physics has called into question determinism. But determinism and causality are not necessarily the same thing. we may not be able to determine or predict an qm outcome but we can identify the set of causal factors. [T]he unity of the set of causal factors is the cause.

KF: JDFL: You are right, once we see the significance of necessary causal factors, we decouple cause from determinism.

RH7: Cites JDFL & responds:

we may not be able to determine or predict an qm outcome but we can identify the set of causal factors. the unity of the set of causal factors is the cause.

Well that’s the problem. Not only can we not determine the outcome, we can not definitively know the cause. As an alternative, Bohm’s quantum mechanics is deterministic and non-local – though I’m not sure you would find his idea of a universal wave function any better.

This sets up my own response:

_____________________

>> Re:

that’s the problem. Not only can we not determine the outcome, we can not definitively know the cause . . . [highlights added]

Let us mark key distinctions:

a: Knowing — per identified necessary causal factors — that something, X, is subject to causal influences,

vs.

b: Knowing a sufficient set of causal factors that WILL cause X,

vs.

c: Knowing the necessary and sufficient cluster of causal factors for X,

vs.

d: Knowing a sufficient set of causal circumstances in which a distribution of cases Y occurs, in which we may observe some y1, or y2, or y3, etc. That is, we have a sufficient causal framework for a stochastic process from population Y of possibilities, that will lead to some outcome from the population, and thus may lead to observed samples y1, y2, etc that in turn may help us model Y.

Case a is the necessary causal factor case, it identifies enabling factors that PERMIT or ENABLE but do not FORCE the occurrence of X.

Cases b or c, by contrast, are sufficient to FORCE — determine — that an event X will occur. Case c is more stringent yet: it is a cluster that must be met in any situation that X occurs.

Case d is sufficient, not for any given yk, but to set up a stochastic sampling from Y.

In any of cases a – d, causes are at work, perhaps through mechanisms that we have not elucidated, and in some cases may not even be able to elucidate.

In many quantum mechanical situations, what we have is case d.

The possibilities a – d also point to the sharp distinction between knowing that an observed outcome is caused, and knowing the sufficient and/or the necessary and sufficient cluster of factors that force the outcome to occur.

What is clear is that, RH7, you keep emphasising that for many quantum cases we do not — and perhaps cannot — know cases b or c, when all that is needed to demonstrate that causality is at work would be a or d. The quantum cases, in fact, typically are cases of d.

All that is required for the main discussion to proceed is that we know that something is caused, and in particular that we are able to identify that there are observed or identifiable conditions under which X of yk do occur, and different ones under which they do or do not (explicitly including, that these have a beginning, or may come to an end), i.e. that they are contingent. That which is contingent — and, please notice the empirical, observational focus — is caused, i.e. acts under the influence of factors that may enable or contribute to or may even force its occurrence, depending on specifics.

[Citing Wikipedia on cause, against known interest, from 6 in the same thread:

Causality is the relationship between an event (the cause) and a second event (the effect), where the second event is understood as a consequence of the first.[1]

In common usage Causality is also the relationship between a set of factors (causes) and a phenomenon (the effect). Anything that affects an effect is a factor of that effect. A direct factor is a factor that affects an effect directly, that is, without any intervening factors. (Intervening factors are sometimes called “intermediate factors.”)

Though the causes and effects are typically related to changes or events, candidates include objects, processes, properties, variables, facts, and states of affairs; characterizing the causal relationship can be the subject of much debate . . . .

Causes are often distinguished into two types: Necessary and sufficient.[7] A third type of causation, which requires neither necessity nor sufficiency in and of itself, but which contributes to the effect, is called a “contributory cause.”[8]

Necessary causes:

If x is a necessary cause of y, then the presence of y necessarily implies the presence of x. The presence of x, however, does not imply that y will occur.

Sufficient causes:

If x is a sufficient cause of y, then the presence of x necessarily implies the presence of y. However, another cause z may alternatively cause y. Thus the presence of y does not imply the presence of x.

Contributory causes:

A cause may be classified as a “contributory cause,” if the presumed cause precedes the effect, and altering the cause alters the effect. It does not require that all those subjects which possess the contributory cause experience the effect. It does not require that all those subjects which are free of the contributory cause be free of the effect. In other words, a contributory cause may be neither necessary nor sufficient but it must be contributory.[9][10]

J. L. Mackie argues that usual talk of “cause,” in fact refers to INUS conditions (insufficient but non-redundant parts of a condition which is itself unnecessary but sufficient for the occurrence of the effect).[11] For example, a short circuit as a cause for a house burning down. Consider the collection of events: the short circuit, the proximity of flammable material, and the absence of firefighters. Together these are unnecessary but sufficient to the house’s burning down (since many other collections of events certainly could have led to the house burning down, for example shooting the house with a flamethrower in the presence of oxygen etc. etc.). Within this collection, the short circuit is an insufficient (since the short circuit by itself would not have caused the fire, but the fire would not have happened without it, everything else being equal) but non-redundant part of a condition which is itself unnecessary (since something else could have also caused the house to burn down) but sufficient for the occurrence of the effect .]

This is not assumption, it is empirically based.

Now, we move to a different level: we live in an observed cosmos that credibly had a beginning, on the usual timeline some 13.7 BYA.

Whether we are in cases a or d, we are in a situation of contingency and presence of cause.

Going beyond, the observed cosmos is credibly locally exceedingly fine tuned (cf also here [kindly, watch the vids]), such that relatively minor variations in parameters and physical laws that we have no reason to believe are constrained, would make the cosmos radically inhospitable to C-Chemistry, cell based life. The Hoyle law-monkeying issue in particular arises in respect of the resonance responsible for the cluster of most common elements of the universe we observe: H, He, C, O. These elements turn out to be — surprise — the core elements of life, and to have astonishing properties reflected in the physics and chemistry of water, H2O, and the rich world of Carbon chemistry.

See why Hoyle inferred a “put-up job” as best most plausible explanation? As he said:

From 1953 onward, Willy Fowler and I have always been intrigued by the remarkable relation of the 7.65 MeV energy level in the nucleus of 12 C to the 7.12 MeV level in 16 O. If you wanted to produce carbon and oxygen in roughly equal quantities by stellar nucleosynthesis, these are the two levels you would have to fix, and your fixing would have to be just where these levels are actually found to be. Another put-up job? . . . I am inclined to think so. A common sense interpretation of the facts suggests that a super intellect has “monkeyed” with the physics as well as the chemistry and biology, and there are no blind forces worth speaking about in nature. [F. Hoyle, Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 20 (1982): 16]

I do not believe that any physicist who examined the evidence could fail to draw the inference that the laws of nuclear physics have been deliberately designed with regard to the consequences they produce within stars. [[“The Universe: Past and Present Reflections.” Engineering and Science, November, 1981. pp. 8–12]

And, here’s the trick: even on case d, that obtains, as a multiverse set up so that the local cluster of possibilities at the “knee” where our observed cosmos happens to be, requires a “cosmic bakery” that itself would be fine tuned. (Leslie’s isolated fly on the wall swatted by a bullet discussion here points out why this inference is highly reasonable.)

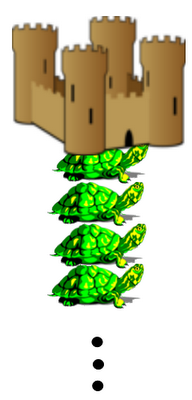

This points onward to an alternative that is astonishing but perfectly logical: Case e. Let us observe, that which is under case a is contingent, and has possible conditions under which it may not be actualised.

Now, let us ask: what of something, Z, that has no necessary causal factors, i.e no circumstances in possible worlds, in which it is not actual?

Since Z has no beginning, it is not caused, it is a necessary being. A good first example is abstract, necessarily true propositions like the truth in the statement 2 + 3 = 5. But of course such is both mental — truths are held in minds and are meaningful assertions — and inert in itself.

Is there another possible class? Not matter per observations in our world, as we know it is causally dependent.

That is, we have reasons to infer to the possibility and credibility of a mental necessary being, which is present in all possible worlds. One with power, intent and knowledge to create a world such as the one we inhabit.

Or, again, we see that there is a possible class of being that does not have a beginning, and cannot go out of existence; such are self-sufficient, have no external necessary causal factors, and as such cannot be blocked from existing. And it is commonly held that once there is a serious candidate to be such a necessary being, if the candidate is not contradictory in itself [i.e. if it is not impossible], it will be actual.

Or, yet again, we could arrive at effectively the same point another way, one which brings out what it means to be a serious candidate to be a necessary being:

If a thing does not exist it is either that it could, but just doesn’t happen to exist, or that it cannot exist because it is a conceptual contradiction, such as square circles, or round triangles and so on. Therefore, if it does exist, it is either that it exists contingently or that it is not contingent but exists necessarily (that is it could not fail to exist without contradiction). [–> The truth reported in “2 + 3 = 5” is a simple case in point; it could not fail without self-contradiction.] These are the four most basic modes of being and cannot be denied . . . the four modes are the basic logical deductions about the nature of existence.

That is, since there is no external necessary causal factor, such a being — if it is so — will exist without a beginning, and cannot cease from existing as one cannot “switch off” a sustaining external factor. Another possibility of course is that such a being is impossible: it cannot be so as there is the sort of contradiction involved in being a proposed square circle. So, we have candidates to be necessary beings that may not be possible on pain of contradiction, or else that may not be impossible, equally on pain of contradiction.

In addition, since matter as we know it is contingent, such a being will not be material. The likely candidates are: abstract, necessarily true propositions and an eternal mind, often brought together by suggesting that such truths are held in such a mind.

Strange thoughts, perhaps, but not absurd ones.

So also, if we live in a cosmos that (as the cosmologists tell us) seems — on the cumulative balance of evidence — to have had a beginning, then it too is credibly caused. The sheer undeniable actuality of our cosmos then points to the principle that from a genuine nothing — not matter, not energy, not space, not time, not mind etc. — nothing will come. So then, if we can see things that credibly have had a beginning or may come to an end; in a cosmos of like character, we reasonably and even confidently infer that a necessary being is the ultimate, root-cause of our world; even through suggestions such as a multiverse (which would simply multiply the contingent beings).

Of course, God is the main candidate to be such a necessary being. (As we saw, truths that are eternal in scope, i.e. true propositions, are another class of candidates, and are classically thought of as being eternally resident in the mind of God.)

Once that is seriously on the table, it radically shifts the balance of our epistemological evaluations of best explanations of a great many things: origin of the observed cosmos, origin of life, origin of body plans, origin of humanity with mind and under moral governance.

And, a prime line of evidence pointing to the credibility of this view, is the strong inductive evidence we have that here are signs of design that are reliable. Signs that appear in two relevant contexts: our world of human art, which allows us to see and analyse why such signs are credibly reliable and are tested and shown strongly reliable, and in the world around us, in cell based life and the credible fine tuning of the cosmos. In particular, we are looking at functionally specific complex organisation and information that often embeds irreducibly complex cores of co-matched parts that are necessary factors for he observed performance.

In short, the updated design view of our world and ourselves, is anchored on an empirical basis, and has a wider context of worldviews analysis on cause that makes it inherently highly plausible.

Even, on case d.>>

______________________

So, credibly knowing that something X or yk is caused, is different from knowing a sufficient or necessary and sufficient cluster of causal factors [cases b and c] that forces the event to happen.

And, in particular, the insight that there are cases in which necessary causal factors act, a, points to the difference between contingent and necessary being.

So also, on d, we can see that even through a multiverse of a quantum world in which we see populations of possible outcomes, a contingent universe such as we credibly inhabit, points beyond itself to a necessary and powerful, intelligent and purposeful being as its most reasonable explanation.

Which opens up a world of possibilities. END