In a recent post, entitled, Was Paley a mechanist?, I argued that Paley’s argument from design in no way presupposes a mechanistic philosophy of life, and that Paley’s philosophy of Nature was much closer to that of Aristotle than is commonly supposed. In today’s post, which is a follow-up of my latest essay, Building a bridge between Scholastic philosophy and Intelligent Design, I shall attempt to lay to rest a long-standing myth: the myth that the Intelligent Design movement is tied to a mechanistic view of life. I propose to lay the evidence before my readers, and let them draw their own conclusions.

1. What is a mechanist, and why does Professor Feser think that Professor Dembski is one?

|

|

Left: A toy ship. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In his book, The Design Revolution (Intervarsity Press, 2004, pp. 132-133), leading Intelligent Design proponent Professor William Dembski identified the hallmark features of design, which are that “information is conferred on an object from outside the object and that the material constituting the object, apart from that outside information, does not have the power to assume the form it does. For instance, raw pieces of wood do not by themselves have the power to form a ship.” Professor Feser has criticized this passage, claiming that it shows that Intelligent Design proponents have a mechanistic view of life. However, Dembski was not comparing a living thing to a ship in the passage above. All the passage implies is that the design of (say) the first living thing is like the building of a ship in two vital respects: first, the form is imposed from outside; and second, the molecules composing a living thing have no built-in capacity to assemble themselves into a ship.

Right: An oak tree in Corsica. Image courtesy of Amada44 and Wikipedia.

In the passage quoted above, Professor Dembski contrasted intelligent design with the natural process whereby an acorn grows into an oak. Professor Feser has criticized him for doing this, arguing that “Dembski seems explicitly to contrast the ID view of natural objects with the Aristotelian conception of ‘nature'”. In reality, however, Dembski is contrasting intelligent design with natural processes which lack foresight, which is a quite different thing.

_____________________________________________________________________

Professor Feser has publicly accused leading Intelligent Design proponent William Dembski of holding to “a ‘mechanistic’ conception of life”, and he adds that “Dembski makes it clear that he accepts this mechanistic approach to the world” (“Intelligent Design” theory and mechanism , April 10, 2010).

Before we proceed any further, we might profitably ask: what does it mean to have a “mechanistic” conception of life? What does “mechanism” mean anyway? Wikipedia gives a pretty good definition of the term in its article, Mechanism (philosophy):

Mechanism is the belief that natural wholes (principally living things) are like machines or artifacts, composed of parts lacking any intrinsic relationship to each other, and with their order imposed from without. Thus, the source of an apparent thing’s activities is not the whole itself, but its parts or an external influence on the parts.

Professor Feser confirms that it is this sense of the term “mechanism” that he has in mind, when he writes:

As I have said many times, it is its eschewal of immanent final causality that makes ID theory “mechanistic” in the specific sense of “mechanism” that A-T philosophers object to…

(Thomism versus the design argument, March 15, 2011)

and again:

The ID approach is, for methodological purposes, to treat organisms at least as if they were artifacts; and that just is to treat them as if they were devoid of immanent final causality, because an artifact just is, by definition as it were, something whose parts are not essentially ordered to the whole they compose.

(ID, A-T, and Duns Scotus: A further reply to Torley, April 25, 2010)

In what follows, I shall endeavor to establish beyond reasonable doubt that Professor William Dembski is not, and has never been, a mechanist in the sense alleged by Feser, and that the Intelligent Design movement’s willingness to debate atheistic mechanists on their own terms in no way implies that they accept a mechanistic conception of life.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

2. Three vital pieces of evidence which show that Intelligent Design proponent Professor William Dembski is not a mechanist

|

Duck at the Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh. Image courtesy of Kitkatcrazy and Wikipedia.

The duck test is a humorous term for a form of inductive reasoning, usually expressed as follows: “If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.” Below, I put forward several pieces of evidence showing that Intelligent Design proponent Professor William Dembski does not talk like a mechanist. On the basis of this evidence, it is reasonable to conclude that Dembski is not a mechanist.

_____________________________________________________________________

Intelligent Design proponents have been accused of espousing a mechanistic view of life. Is there any merit to this accusation? In addressing this charge, it will obviously be useful to look at the writings of leading ID proponent Professor William Dembski, whose writings have attracted a fair amount of flak from some Thomistic critics of Intelligent Design, for their alleged endorsement of mechanism. So let’s have a look at what Dembski actually says. I’d like to put forward three vital pieces of evidence which clear him of the charge of mechanism.

Iten #1. In a post entitled, Does ID presuppose a mechanistic view of nature? (April 18, 2010), Professor Dembski wrote:

I have to confess that I’ve always been much more a fan of Plato than of Aristotle, and so I don’t quite see the necessity of forms being realized in nature along strict Aristotelian lines. Even so, nothing about ID need be construed as inconsistent with Aristotle and Thomas.…

For the Thomist/Aristotelian, final causation and thus design is everywhere. Fair enough. ID has no beef with this. As I’ve said (till the cows come home, though Thomist critics never seem to get it), the explanatory filter has no way or ruling out false negatives (attributions of non-design that in fact are designed). I’ll say it again, ID provides scientific evidence for where design is, not for where it isn’t…

ID is happy to let a thousand flowers bloom with regard to the nature of nature provided it is not a mechanistic, self-sufficing view of nature.

Item #2. Six years earlier, on January 17, 2004, Professor William Dembski gave a talk at at Grace Valley Christian Center, Davis, California, as part of the Faith and Reason series sponsored by Grace Alive! and Grace Valley Christian Center. In the course of the lecture, which was entitled, Intelligent Design: Yesterday’s Orthodoxy, Today’s Heresy (January 17, 2004), Professor Dembski made the following comments about the watch metaphor for the cosmos:

I am a much bigger fan of the Church Fathers than I am of William Paley. I like Paley and think he has a lot of good insights. But I think the watch metaphor was in many ways unfortunate. It is faulty, because the world is not like a watch.

… As Christians, we believe that God is not an absentee landlord. God creates the world but then he also interacts with it.

The watch metaphor is the type of metaphor that we get from a mechanical philosophy, where things work automatically, one thing bumping into another as chain reactions, with things working themselves out. If you have a perfect watch that keeps perfect time and never needs winding, it will go on for ever.

In the above passages, Professor Dembski explicitly repudiates a mechanistic philosophy of life. You can’t get much clearer than that.

Item #3. In his book, The Design Revolution (Intervarsity Press, 2004, pp. 66-67), Dembski matter-of-factly chronicles the history of the “design argument”, which he construes in the broadest sense to include both Aquinas’ teleological argument and the more recent “mechanical” design arguments:

Throughout the Christian era, theologians have argued that nature exhibits features which nature itself cannot explain but which instead require an intelligence beyond nature.… Aquinas’s fifth proof for the existence of God is perhaps the best known of these.

With the rise of modern science in the seventeenth century, design arguments took a mechanical turn. The mechanical philosophy that was prevalent at the birth of modern science viewed the world as an assemblage of material particles interacting by mechanical forces. Within this view, design was construed as externally imposed form on preexisting inert matter. Paradoxically, the very clockwork universe that early mechanical philosophers like Robert Boyle (1627-1691) used to buttress design in nature was in the end probably more responsible than anything for undermining design in nature. Boyle (in 1686) advocated the mechanical philosophy because he saw it as refuting the immanent teleology of Aristotle and the Stoics, for whom design arose as a natural outworking of natural processes…

Over the subsequent centuries, however, what remained was the mechanical philosophy and what fell away was the need to invoke miracles or God as designer. Henceforth, purely mechanical processes could do all the design work for which Aristotle and the Stoics had required an immanent natural teleology and for which Boyle and the British natural theologians required God…

The British natural theologians of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, starting with Robert Boyle and John Ray (1627-1705) and culminating in the natural theology of William Paley (1743-1805), looked to biological systems for convincing evidence that a designer had acted in the physical world… For many [this] was the traditional Christian God, but for others it was a deistic God, who had created the world but played no ongoing role in governing it.

It should be abundantly clear that the author of the above passage is deeply unhappy about the damage inflicted by a mechanical philosophy of science on the traditional “design argument” for the existence of God, and that he is all too aware of the shortcoming sof Paley’s design argument. The irony is that the above passage in Dembski’s writings is actually quoted by Professor Feser, in a post entitled, Thomism versus the design argument (March 15, 2011)!

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

3. Is there any sense in which Intelligent Design proponents can be called mechanists?

A reader of my last post, entitled, Building a bridge between Scholastic philosophy and Intelligent Design, who goes under the handle of Mung, wrote a very thoughtful response in which he quoted a passage from an encyclopedia entry on Intelligent Design written by Professor William Dembski (in Lindsay Jones’s Encyclopedia of Religion, Macmilllan, 2003) which seemed to undercut my claim that the ID and Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy are mutually compatible:

We need here draw a clear distinction between creation and design. We need to do this doubly because it’s very convenient to identify intelligent design with creationism…

Creation is always about the source of being of the world. Design is about arrangements of pre-existing materials that point to an intelligence. Creation and design are therefore quite different. We can have creation without design and design without creation.

The reader (Mung) then made the following observation:

The problem then, as I see it, as that these pre-existing materials are conceived of as self-existing, and ID has no answer to, or even accepts that view. And this is precisely what is the view of the mechanistic philosophy. So ID in practice buys into the mechanistic philosophy of nature.

Yet the mechanistic philosophy of nature is wrong, and it is contrary to the philosophy of nature of classical theism. (Or so Feser and other Thomists would argue.)

The foregoing argument merits a substantive response. I’d like to make four points in reply.

First, as a description of biological Intelligent Design, Professor Dembski’s remark is perfectly correct. However, I would like to point out that “arrangements of pre-existing materials” doesn’t necessarily mean “arrangements of pre-existing materials which retain their old form.” It could mean “arrangements of pre-existing materials which retain nothing but their underlying prime matter” – in which case, since matter cannot exist without form, the pre-existing material here is no longer self-existing. (That would be the Thomistic view.)

Alternatively, it could mean “arrangements of pre-existing materials which retain their old substantial form but gain a new high-level substantial form,” along the lines envisaged by some of the medieval Scholastic philosophers who (unlike Aquinas) believed in a multiplicity of substantial forms, as I pointed out in my previous post. In that case, additional argumentation would be required to show that the pre-existing material with its lower-level substantial form was not self-existent.

Second, I would like to add that Professor Dembski, in the encyclopedia entry quoted above, was simply pointing out the obvious: merely establishing that living things were designed fails to prove that there is a Creator of the cosmos, Who keeps it in being. That has to be demonstrated separately.

Third, Dembski himself believes that not only life, but the cosmos itself, bears the hallmarks of intelligent design. In a 2003 article entitled, Infinite Universe or Intelligent Design?, Professor Dembski stated that “In the theory of intelligent design, specified complexity is a reliable empirical marker for design,” and he also declared that “the specified complexity in artifacts is identical with the specified complexity in natural systems (be they cosmological or biological).” (This, by the way, is the only respect in which living things are the same as artifacts, from the perspective of Intelligent Design theory: both exhibit specified complexity.)

In the passage above, Dembski refers to “the specified complexity in natural systems, be they cosmological or biological.” Presumably Dembski is referring to the specified complexity of the laws of Nature. I would argue that the specified complexity of these laws cannot be construed in mechanistic terms. For the laws of Nature are not “added onto” pre-existing stuff; rather, they define the very warp and woof of the material world – i.e. what it is for something to be a body at all. A material thing would no longer be a thing, in the absence of laws. Its very existence as a thing depends on them. Consequently the Being which is the Author of these cosmic laws is also the Author of the cosmos’ existence: in other words, none other than the Creator of the cosmos.

Fourth and finally, in his prepared text for his debate with Christopher Hitchens at Prestonwood Church, Plano, Texas, on 18 November 2010, entitled, Does a Good God Exist?, Professor Dembski spelt out how he believes the case for a Creator of the cosmos should be made, after the Intelligent Design argument for a Cosmic Designer has been put forward:

Just as getting from Darwinian evolution to atheism is not a big stretch, so getting from design in biology to theism is not a big stretch… By itself, my argument establishes a designer behind the universe (a Kantian architect, if you will). For the purposes of this debate, however, I think we’re ready to close escrow.

Note that the full positive case for God’s existence can and should be fleshed out. Typically, such a case flows from critical reflection on the big questions of life: Why is there something rather than nothing? Where did we come from? Where are we going? Why should we take morality seriously? Why is the world comprehensible to our minds? Why does mathematics, presumably a human invention, have such a precise purchase on physical reality? Each of these questions can, in my view, be answered better within a theistic than atheistic worldview.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

4. Is there any sense in which Intelligent Design proponents can be called mechanists?

|

The ribosome is a molecular machine which is found in all living things. It’s a vital component of cells, and it synthesizes protein chains. This is a picture of just part of a ribosome. It shows the atomic structure of the 50S Subunit from the halobacterium Haloarcula marismortui. Proteins are shown in blue and the two RNA strands in orange and yellow. The small patch of green in the center of the subunit is the active site. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

_____________________________________________________________________

At this point, the reader might wish to ask: if Intelligent Design proponents such as Professor Dembski are not mechanists, then why do they adopt mechanistic terminology in describing how organisms work? Here, for instance, is an excerpt from an article by ID proponent Casey Luskin, entitled, Molecular Machines in the Cell:

Long before the advent of modern technology, students of biology compared the workings of life to machines. In recent decades, this comparison has become stronger than ever. As a paper in Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology states, “Today biology is revealing the importance of ‘molecular machines‘ and of other highly organized molecular structures that carry out the complex physico-chemical processes on which life is based.” Likewise, a paper in Nature Methods observed that “[m]ost cellular functions are executed by protein complexes, acting like molecular machines.”

In the very next paragraph, however, Luskin clarifies exactly what he means by a molecular machine:

A molecular machine, according to an article in the journal Accounts of Chemical Research, is “an assemblage of parts that transmit forces, motion, or energy from one to another in a predetermined manner.” A 2004 article in Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering asserted that “these machines are generally more efficient than their macroscale counterparts,” further noting that “[c]ountless such machines exist in nature.” Indeed, a single research project in 2006 reported the discovery of over 250 new molecular machines in yeast alone!

It should be noted that Luskin nowhere states that an organism is a machine. Moreover, Luskin defines “machine” in a very specific sense – not as a mere assemblage of parts, but as “an assemblage of parts that transmit forces, motion, or energy from one to another in a predetermined manner.” Finally, this description is said to apply not to whole organisms, but to certain systems functioning inside organisms. Hence the above quote in no way supports the charge of philosophical mechanism – i.e. denial of immanent final causality – which is often hurled at Intelligent Design advocates.

The Catholic philosopher and Intelligent Design advocate Jay Richards has addressed the accusation that Intelligent Design is mechanistic in his book, God and Evolution (Discovery Institute, Seattle, 2010). In chapter 12, in an essay entitled, “Separating the wheat from the chaff”, he writes:

[E]ven if parts of organisms are literally machines, it doesn’t follow that organisms are, any more than it follows that because Van Gogh’s Starry Night is made of paint, it’s just paint. (2010, p. 228)

Finally, Professor William Dembski himself has addressed the charge of mechanism head-on, in a post entitled, Does ID presuppose a mechanistic view of nature? (18 April, 2011). He writes:

[I]n focusing on the machinelike features of organisms, intelligent design is not advocating a mechanistic conception of life. To attribute such a conception of life to intelligent design is to commit a fallacy of composition. Just because a house is made of bricks doesn’t mean that the house itself is a brick. <bLikewise just because certain biological structures can properly be described as machines doesn't mean that an organism that includes those structures is a machine. Intelligent design focuses on the machinelike aspects of life because those aspects are scientifically tractable and precisely the ones that opponents of design purport to explain by physical mechanisms. Intelligent design proponents, building on the work of Polanyi, argue that physical mechanisms (like the Darwinian mechanism of natural selection and random variation) have no inherent capacity to bring about the machinelike aspects of life.

In a post entitled, In Praise of Subtlety (April 22, 2010), I coined the term nano-biomechanism to describe “the view that the organisms have tiny components that work like machines” – a view which, I added “does not entail that organisms are machines.” Intelligent Design, I wrote, “strongly endorses nano-biomechanism”, in this sense of the word.

Thomist scholars are quite right to point out that from a teleological perspective, the parts of a living thing display a profound kind of unity that no man-made artifact possesses. But a mechanical perspective is also indispensable, for describing the workings of living cells. A recent report by Claire O’Connell in New Scientist (13 July 2012) on a lecture by the acclaimed geneticist Craig Venter at Trinity College Dublin (organized by the Royal Irish Academy as part of Euroscience Open Forum 2012), highlights this point:

“All living cells that we know of on this planet are ‘DNA software’-driven biological machines comprised of hundreds of thousands of protein robots, coded for by the DNA, that carry out precise functions,” said Venter. “We are now using computer software to design new DNA software.”

The digital and biological worlds are becoming interchangeable, he added, describing how scientists now simply send each other the information to make DIY biological material rather than sending the material itself.

Venter also outlined a vision of small converter devices that can be attached to computers to make the structures from the digital information – perhaps the future could see us distributing information to make vaccines, foods and fuels around the world, or even to other planets. “This is biology moving at the speed of light,” he said.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

5. An argument about ships: does Professor Dembski commit himself to a mechanistic view of life, in his writings on design?

|

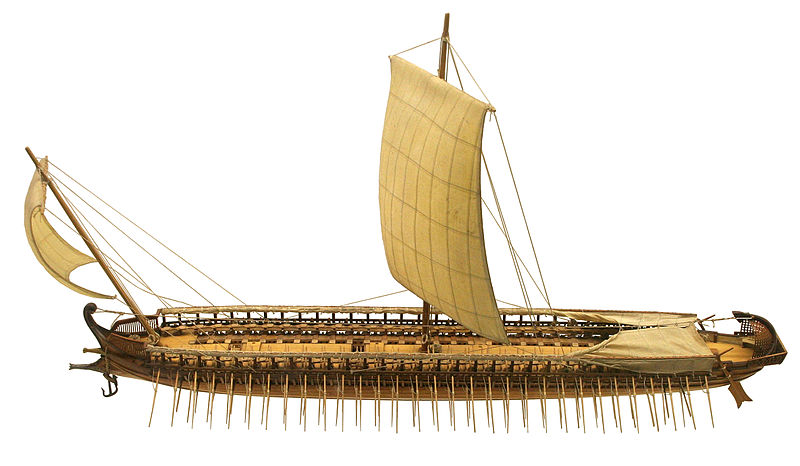

Model of a Greek trireme. Deutsches Museum, Munich, Germany. Image courtesy of Sting and Wikipedia.

Leading ID proponent William Dembski has compared the intelligent design of the first living organism to the building of a ship – a comparison which displeases Thomist philosopher Edward Feser, since it seems, at first glance, to suggest that the information in a living cell is not “internal” to it but is merely an artificial arrangement imposed from outside. Intelligent Design proponents reply that the immanent finality of a natural object can be imposed from outside, as shown above in section 1.3.

_____________________________________________________________________

In a blog post entitled, Reply to Torley and Cudworth (May 4, 2011), Professor Feser cites a passage from leading Intelligent Design proponent Professor William Dembski, which, he argues, shows that ID advocates are committed to a mechanistic view of living things:

[I]n discussing Aristotle in The Design Revolution, Dembski identifies “design” with what Aristotle called techne or “art” (pp. 132-3). As Dembski correctly says, “the essential idea behind these terms is that information is conferred on an object from outside the object and that the material constituting the object, apart from that outside information, does not have the power to assume the form it does. For instance, raw pieces of wood do not by themselves have the power to form a ship.” This contrasts with what Aristotle called “nature,” which (to quote Dembski quoting Aristotle) “is a principle in the thing itself.” For example (again to quote Dembski’s own exposition of Aristotle), “the acorn assumes the shape it does through powers internal to it: the acorn is a seed programmed to produce an oak tree” – in contrast to the way the “ship assumes the shape it does through powers external to it,” via a “designing intelligence” which “imposes” this form on it from outside.

Having made this distinction, Dembski goes on explicitly to acknowledge that just as “the art of shipbuilding is not in the wood that constitutes the ship” and “the art of making statues is not in the stone out of which statues are made,” “so too, the theory of intelligent design contends that the art of building life is not in the physical stuff that constitutes life but requires a designer“ (emphasis added). In other words, living things are for ID theory (at least as Dembski understands it) to be modeled on ships and statues, the products of techne or “art,” whose characteristic “information” is not “internal” to them but must be “imposed” from “outside.” And that just is what A-T philosophers mean by a “mechanistic” conception of life…

Now these quotes seem to me to provide clear evidence that Dembski rejects the Aristotelian distinction between art and nature, and in particular that he would assimilate natural objects to artifacts…

In response, I would like to point out that Professor Dembski was not comparing a living thing to a ship in the passage cited above. He could not have been doing so, because if he had been, then he would have been saying that a living thing is like a ship and not like an oak – which makes absolutely no sense, as an oak is a living thing, and a ship is not. Thus Professor Feser’s charge that Dembski assimilates natural objects to artifacts is wide of the mark.

What I believe foregoing passage says about life is that the design of (say) the first living thing is like the building of a ship, and unlike the natural growth of an oak, in two vital respects: first, the form is imposed from outside; and second, the molecules composing a living thing have no built-in capacity to assemble themselves into a living thing.

Neither of these facts in any way undermines the immanent finality which is present in living organisms and in all natural objects. It was argued in section 1.3 above that the substantial form of a natural object can indeed be imposed from outside, upon prime matter, and it was argued in section 3.5 above that in the opinion of many medieval Scholastic philosophers, a substantial form could even be imposed upon an object with a pre-existing substantial form. And in my previous post, I argued that just because the parts of a living thing have an inherent tendency to function together, that does not imply that they have a tendency to come together in the first place.

In a more recent blog post, entitled, Reply to Torley and Cudworth (May 4, 2011), Feser graciously acknowledges my efforts (see my post, An argument about ships, oaks, corn and teleology, April 18, 2011) to construe Professor Dembski’s above-cited remarks in The Design Revolution (pp. 132-133) in a sense which can be reconciled with Aristotelian Thomism. However, Feser thinks that even if I were right on this point, it wouldn’t prove much:

The most Torley can reasonably say is that there is arguably a way of interpreting, or even of modifying, developing, or reconstructing Dembski’s position so as to make it compatible with A-T.

In reply: since my sole aim, in writing that post, was to show that Intelligent Design is broadly compatible with Aristotelian Thomism, I think I can be fairly said to have accomplished my objective. Feser has not provided any convincing argument to show that Intelligent Design and belief in immanent finality are incompatible.

In a blog post entitled, Reply to Torley and Cudworth (May 4, 2011), he puts forward an additional reason, based on Dembski’s remarks above, for concluding that Dembski’s view of life is a mechanistic one. This reason has to do with Dembski’s contrast between art and nature:

Dembski seems explicitly to contrast the ID view of natural objects with the Aristotelian conception of “nature” and explicitly to identify the ID view of natural objects with the Aristotelian notion of “art.” This is a very odd thing to do if what one “actually” intends is to leave an Aristotelian interpretation open as one possible way among others of construing ID….

I believe that Feser has misunderstood Dembski here. In the passage from The Design Revolution cited above, Professor Dembski did not contrast the Intelligent Design view of natural objects with the Aristotelian conception of “nature”. Rather, he contrasted the process of intelligent design with the Aristotelian conception of natural development, in which a living thing assumes the powers it has through processes internal to it.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

6. Has Professor William Dembski ever denied the existence of immanent finality in Nature?

|

An ice block near Joekullsarlon in Iceland. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Professor Feser alleges that Intelligent Design proponent William Dembski denies immanent finality, such as the tendency of water to melt into ice. In fact, nowhere in his writings does Professor Dembski reject immanent finality. What he does say, however, is that immanent finality cannot be used as a scientific argument for the existence of God. The reason is obvious: science deals with what is quantifiable, and immanent finality per se is not quantifiable.

_____________________________________________________________________

Despite these clarifications, Professor Feser insists that Professor Dembski’s own writings make it abundantly clear that he denies the reality of immanent final causality:

In other ways too Dembski makes it clear that he accepts this mechanistic approach to the world.

For example, at p. 140 of The Design Revolution, Dembski flatly asserts that “lawlike [regularities] of nature” such as “water’s propensity to freeze below a certain temperature” are ‘as readily deemed brute facts of nature as artifacts of design” and thus ‘can never decisively implicate design’; only “specified complexity” can do that. But for A-T [Aristotelian-Thomism], such regularities are paradigm examples of final causality… That Dembski considers it at least in principle possible that such causal regularities are ‘brute facts’ which can never decisively implicate design suffices to show that his conception of causality is mechanistic in the relevant sense, viz. one which eschews inherent final causality.

(“Intelligent Design” theory and mechanism , April 10, 2010)

Now, a common-sensical interpretation of these passages in Dembski’s writings would begin by asking: what kind of arguments for design does Dembski have in mind, when he writes that the laws of nature ‘can never decisively implicate design’? Is he speaking of philosophical arguments for design, which Thomists appeal to, or is he speaking of mathematical and scientific arguments? Given that Professor Dembski is a qualified mathematician, and that he wrote his book for the scientific community, it is reasonable to infer that he was thinking of mathematical and scientific arguments when he wrote the comments quoted above.

In other words, all that Dembski is saying is that scientists cannot establish that the world was designed, from the mere existence of laws of Nature. To make a scientific case for Design in Nature, you need to argue from the occurrence of specified complexity in natural systems. Nothing in the above-cited passage puts Dembski at odds with Thomistic philosophy, and nothing in the passage implies that he rejects immanent final causality.

In the same post, Professor Feser added:

[T]hat some A is an efficient cause of some effect or range of effects B is for A-T [Aristotelian-Thomism] unintelligible unless we suppose that generating B is the final cause or end at which A is naturally directed. Even the simplest causal regularities thus suffice “decisively” to show that there must be a supreme ordering intelligence keeping efficient causes directed toward their ends from instant to instant, at least if Aquinas’s Fifth Way is successful.

Professor Dembski’s response in his post, Does ID presuppose a mechanistic view of nature? (April 18, 2010), bears repeating:

For the Thomist/Aristotelian, final causation and thus design is everywhere. Fair enough. ID has no beef with this. As I’ve said (till the cows come home, though Thomist critics never seem to get it), the explanatory filter has no way or ruling out false negatives (attributions of non-design that in fact are designed). I’ll say it again, ID provides scientific evidence for where design is, not for where it isn’t…

Why, one might ask, can’t immanent finality be used in a scientific argument for the existence of a Designer? The reason is very simple: science deals with what is quantifiable, and immanent finality per se is not quantifiable.

It should be clear by now that Feser’s criticism of Dembski’s philosophical position is predicated on a mistaken premise: namely, that Dembski was making a philosophical argument for a Designer of life in The Design Revolution. As the above quote shows, Dembski is arguing on the basis of scientific evidence. This misunderstanding of Feser’s also explains why his charge that Intelligent Design is at odds with classical theism, is totally wide of the mark.

In another blog post entitled, Dembski rolls snake eyes (April 20, 2011), Professor Feser finds fault with ID proponent William Dembski for the following passage in his post, Does ID presuppose a mechanistic view of nature? (April 18, 2010):

ID is willing, arguendo, to consider nature as mechanical and then show that the mechanical principles by which nature is said to operate are incomplete and point to external sources of information (cf. the work of the Evolutionary Informatics Lab — www.evoinfo.org). This is not to presuppose mechanism in the strong sense of regarding it as true. It is simply to grant it for the sake of argument — an argument that is culturally significant and that needs to be prosecuted.

Comments Feser:

…[A]s I have said many times in previous posts, ID’s mechanistic approach puts it at odds with A-T [Aristotelian-Thomism] even if that approach is taken in a merely “for the sake of argument” way. The reason is that a mechanistic conception of the world is simply incompatible with the classical theism upheld by A-T. It isn’t just that a mechanistic starting point won’t get you all the way to the God of classical theism. It’s that a mechanistic starting point gets you positively away from the God of classical theism. Why? Because a mechanistic world is one which could at least in principle exist apart from God. And classical theism holds that the world could not, even in principle, exist apart from God.

I shall respond to this charge of Feser’s in more detail in my next post, but for the time being, I’d like to draw attention to a passage in a 2004 article by Professor William Dembski, entitled, Intelligent Design: Yesterday’s Orthodoxy, Today’s Heresy, which demonstrates unambiguously that he rejects the watch metaphor for the cosmos, and favors instead the metaphor of the lute (invoked by the early Church Fathers), precisely because it makes clear the world’s continual and ongoing dependence on God:

… I think the watch metaphor was in many ways unfortunate. It is faulty, because the world is not like a watch…

… [I]t is entirely appropriate to play, or interact with, a lute after it has been created. That is why I think this is a much better metaphor than that of the watch. As Christians, we believe that God is not an absentee landlord. God creates the world but then he also interacts with it.

The watch metaphor is the type of metaphor that we get from a mechanical philosophy, where things work automatically, one thing bumping into another as chain reactions, with things working themselves out. If you have a perfect watch that keeps perfect time and never needs winding, it will go on for ever. But with a lute, or with any musical instrument, you need a lute player; otherwise it is just sitting there. In fact, it is incomplete without the lute player.

I would like to add that in adopting a mechanistic approach for the sake of argument, Intelligent Design is engaging in a reductio ad absurdum. Essentially it is saying: let’s assume the truth of atheistic mechanism and see where that gets us. Atheistic mechanism is unable to explain patterns in Nature with a high degree of specified complexity. What follows from that, one may ask? What follows is that atheistic mechanism is false. What does not follow is that theistic mechanism is true.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

7. Does Intelligent Design deny that there is an absolute difference between living and non-living things?

|

|

Left: The cells of eukaryotes (left) and prokaryotes (right). The cell is a striking illustration of what Professor Feser refers to as immanent causation. Image courtesy of SciencePrimer (National Center for Biotechnology Information) and Wikipedia.

Right: Living things are the only natural objects which embody a digital code. This picture shows a series of codons in part of a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule. Each codon consists of three nucleotides, usually representing a single amino acid. This mRNA molecule will instruct a ribosome to synthesize a protein according to this code. Image courtesy of TransControl and Wikipedia.

_____________________________________________________________________

In my post, In praise of subtlety (25 April 2010), I wrote that Intelligent Design “does not assume that there are no final causes in nature, or even that there might be no final causes in nature; rather, it simply refrains from invoking final causes in the natural realm while arguing for the existence of a Designer.” I explained that this limitation was a purely methodological one: ID proponents are trying to make a scientific argument for the existence of a Designer, and modern science does not invoke final causes: indeed, many Darwinists even profess to find them unintelligible. (Scientists do of course speak of “biological functions” in the course of their everyday work, but with rare exceptions, they tend to assume that the origin of these biological functions can ultimately be accounted for in reductionist terms, by appealing to: (i) the laws of physics and chemistry; and (ii) non-random winnowing of variations that arise in Nature.)

However, Professor Feser criticizes the Intelligent Design approach in a follow-up piece entitled, ID, A-T, and Duns Scotus: A further reply to Torley, where he argues that it blurs the absolute distinction between living and non-living things:

The ID approach is, for methodological purposes, to treat organisms at least as if they were artifacts; and that just is to treat them as if they were devoid of immanent final causality, because an artifact just is, by definition as it were, something whose parts are not essentially ordered to the whole they compose…

Now, what all-or-nothing differences in kind do in fact exist in the world? That question has to be answered on a case-by-case basis, but I’ve already discussed one case central to the debate over ID, viz. the difference between living and non-living phenomena. Here the standard A-T view is that the difference is an absolute difference in kind deriving from the irreducibility of immanent causation to transeunt causation. But to discuss the “probability” of purely transeunt causal processes giving rise to immanent ones (as ID does) just is precisely to assume, even if only for the sake of argument, that the difference is not really a difference in kind but only in degree, and thus that the sort of irreducible immanent final causality in question is not real.

First, Feser is factually mistaken if he supposes that ID proponents hold that the difference between living and non-living things is merely one of degree. On the contrary, Intelligent Design advocates insist that there is a very sharp difference: living things contain a digital code which has a biological function, and non-living things do not. ID advocates tend to focus on the code, simply because it is mathematically tractable: one can show that the likelihood of such a code arising as a result of blind natural processes is astronomically low – so low that one would not expect such a code to arise even once, in the entire history of the observable universe. That being the case, Intelligent Design (which is readily capable of generating such codes) is the best explanation for the existence of such a code.

Second, Feser has himself conceded in his writings that some Thomists maintain that it is possible for natural processes to generate life. In a post entitled, ID theory, Aquinas, and the origin of life: A reply to Torley (April 16, 2010), he writes:

No contemporary A-T [Aristotelian-Thomistic] theorist accepts the mistaken scientific assumptions that informed Aquinas’s views about spontaneous generation. But might a contemporary A-T theorist hold that there could be some other natural processes (understood non-mechanistically, of course) that have within them the power to generate life, at least as part of an overall natural order that we must in any event regard as divinely conserved in existence? He might, and some do. But the actual empirical evidence for the existence of such processes seems (to say the least) far weaker now than it did in Aquinas’s own day…

I would like to ask Professor Feser: if these Thomists who hold that life can originate by natural processes are not guilty of blurring the distinction between living and non-living things, then why does he think that ID proponents are guilty of doing so? I have already disposed of the claim that ID is committed to a mechanistic view of causality; hence any objection Feser might make in connection with ID proponents discussing the probabilities of life originating by non-foresighted processes (chance plus natural selection) would apply equally well to Thomists.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

8. Two ways in which a Designer might work through andomness

|

Simulation of coin tosses: Each frame, a coin is flipped which is red on one side and blue on the other. The result of each flip is added as a colored dot in the corresponding column. As the pie chart shows, the proportion of red versus blue approaches 50-50. Image courtesy of S. Byrnes and Wikipedia.

_____________________________________________________________________

However, Professor Feser is not finished yet. His final objection to Intelligent Design relates to the way in which Dembski envisages a Designer of Nature might accomplish His goal of imparting information to a system:

In chapter 20 of The Design Revolution, he [Dembski] speaks of the natural world as a “receptive medium” for information and of the designer as “imparting information” and “introducing design” into the world by virtue of “co-opt[ing] random processes and induc[ing] them to exhibit specified complexity.” He offers as an illustration of the sort of thing he has in mind a scenario involving “a device that outputs zeroes and ones and for which our best science tells us that the bits are independent and identically distributed so that zeroes and ones each have probability 50 percent.” Suppose, Dembski says, that “we control for all possible physical interference with this device, and nevertheless the bit string that this device outputs yields an English text-file in ASCII code that delineates the cure for cancer.” Here we have a model, he says, of a designer imparting information to a system, without imparting energy to it…

Now, this way of framing the issue makes perfect sense if you think of living things and other natural objects as artifacts in the Aristotelian sense of “artifacts,” but it makes no sense if you think of them as natural in the Aristotelian sense of “natural.”

Professor Feser seems to assume here that Dembski was putting forward a model of a living thing, and he correctly notes that in reality, a living thing is not at all like the multiple-bit random device envisaged by Dembski. However, in the passage referred to above, Professor Dembski was not speaking of living things specifically; rather, he was simply talking about random processes occurring in the natural world. Dembski nowhere declares that the device which he speaks of is analogous to a living organism.

What, then, could Dembski’s device be analogous to? I’d like to make two proposals – one relating to God’s formation of the first life, and the other relating to Divinely guided mutations in the genome of a living organism.

|

This is what a real protein looks like. The enzyme hexokinase is a protein found even in simple bacteria. Here, it is shown as a conventional ball-and-stick molecular model. For the purposes of comparison, the image also shows molecular models of ATP (an energy carrier found in the cells of all known organisms) and glucose (the simplest kind of sugar) in the top right-hand corner. Courtesy of Tim Vickers and Wikipedia.

First, let’s consider the formation of the first living things. All living organisms need proteins. Indeed, the simplest life-forms known to scientists contain at least 250 different kinds of proteins. However, the pioneering research conducted by Dr. Douglas Axe, of the Biologic Institute, has shown that the formation of even one protein that is capable of performing a biological function of any kind, is such a fantastically improbable event that even over a period of billions of years, its occurrence anywhere on Earth – or even anywhere in the observable universe – would still be astronomically unlikely. One key reason for this is that the amino acids out of which proteins are composed display no built-in biases in their propensity to hook up with each other; the other reason is that the vast majority of possible amino acid strings are incapable of folding properly and doing anything useful. Insofar as amino acids are unbiased in their propensity to combine with each other, they are rather like Dembski’s random bit-machine. Now suppose that an Intelligent Designer were to invisibly guide some amino acids swirling around in the Earth’s primordial ocean, so that they formed a protein. An omnipotent Designer could have accomplished this goal, without having to impart biasing tendencies to the amino acids: if one had examined the behavior of any one of them over a length of time, it would still have appeared random to the eye of a statistician. Suppose now that the same Designer formed 250 different proteins in this way, plus some DNA and other biomolecules required for a minimal cell, and encased them within a membrane. I see no reason in principle why God could not have formed a living thing like that. In so doing, He would have imparted a vast amount of information to non-living matter, and in the process transformed it into a living organism.

|

|

Left: A humpback whale breaching. Image courtesy of Whit Welles and Wikipedia.

Right: The generally accepted textbook picture of whale evolution, from 53 to 38 million years ago. The equations of population genetics predict that – assuming an effective population size of 100,000 individuals per generation, and a generation turnover time of 5 years (according to Dr. Richard Sternberg’s calculations and based on equations of population genetics applied in the Durrett and Schmidt paper, Waiting for Two Mutations: With Applications to Regulatory Sequence Evolution and the Limits of Darwinian Evolution, in Genetics, November 2008, vol. 180 no. 3, pp. 1501-1509), that one may reasonably expect two specific co-ordinated mutations to achieve fixation in the timeframe of around 43.3 million years. (See also the article, Waiting Longer for Two Mutations, by Professor Michael Behe, on the Durrett and Schmidt paper, and see also this post on Uncommon Descent.) When one considers the magnitude of the engineering feat, such a scenario is found to be devoid of credibility. Whales require an intra-abdominal counter current heat exchange system (the testis are inside the body right next to the muscles that generate heat during swimming), they need to possess a ball vertebra because the tail has to move up and down instead of side-to-side, they require a re-organisation of kidney tissue to facilitate the intake of salt water, they require a re-orientation of the fetus for giving birth under water, they require a modification of the mammary glands for the nursing of young under water, the forelimbs have to be transformed into flippers, the hindlimbs need to be substantially reduced, they require a special lung surfactant (the lung has to re-expand very rapidly upon coming up to the surface), and so on. Image courtesy of Jonathan M. and Uncommon Descent.

_____________________________________________________________________

Second, let’s look at mutations. Mutations are commonly said to be “random” – although the term “random” in this context simply means that their frequency of occurrence is supposed to be independent of any benefit that they may confer upon an organism. However, a paradox arises: if mutations really were random in this sense, then there simply isn’t time enough for the large number of mutations that must have been required to transform a land animal into a whale, to have occurred and become fixed within the population at large. (See the caption above for references.) Nor does it help matters to suppose that many of these mutations occurred simultaneously, in parallel, rather than in sequence; for we still have the problem of synchronization. However, despite the apparent mathematical impossibility of the transformation from a land animal to a whale occurring over the space of just a few million years, the fossil record indicates strongly that it actually happened over that time. A reasonable conclusion, then, would be that a Designer arranged for the relevant genes to mutate in a highly specified sequence, so that the transformation from a land animal to a whale would occur as rapidly as possible. And yet, if a geneticist had looked at the propensity of each gene to mutate, in isolation from all the others, he/she would not have noticed any odd patterns. It is only when we look at the whole organism that a pattern emerges. On the micro-level, the behavior of each gene would still appear random.

A brief theological aside, in response to some obvious objections

Some readers may want to ask why the Divinely guided evolution of the whale didn’t happen over a short interval (say, thousands of years) rather than millions. Why did it take so long? Other readers might want to ask why God didn’t make whales in their present form from Day One, given that He is omnipotent. St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430 A.D.) even speculated that God might have created the world in an instant.

The answer that I would tentatively suggest to these questions is that God tends to accomplish His ends with a minimum of effort, where “effort” is defined in terms of how much information needs to be input into a designed system (either at the beginning, or during the course of its development) in order for the system to reach the desired goal. Why does God work in this way? Because that’s the most efficient way. Other things being equal, we expect intelligent beings to be efficient.

The separate creation of each and every kind of organism would be grossly inefficient, because living things fall into nested hierarchies, whose members share a lot of their DNA in common. God would have to duplicate that, every time He created a new organism. It would be far more sensible for God to create an ancestral prototype for each of the major groups of organisms, and then engineer mutations, in order to modify different lines of the prototype’s descendants, so as to create the diversity of life-forms that He intended. That would take less effort.

As for the question of why God took millions rather than thousands of years to make whales, I would answer that a lot of other things were happening on Earth at the time when God was making whales. God was guiding the geological development of the Earth in order to prepare it for the eventual arrival of human beings – i.e. terra-forming – and at the same time, guiding the evolution of entire ecosystems, with a view to creating an biosphere that would be hospitable to human life. If this scenario is correct, then the overnight introduction of a new creature, such as a whale, into the Earth’s marine ecosystems would have caused immense disruption. Now, a religious skeptic might counter that an omnipotent God could easily have prevented the disruption caused by the introduction of a new organism into an ecosystem, simply by working a suitable miracle. However, this objection confuses logical possibility with reasonability. The reasonable way for God to accomplish His ends is with a minimum of effort. Working “mega-miracles” to limit the disruption caused by the overnight introduction of a new creature would have been grossly inefficient, and hence unreasonable behavior for a Deity.

I should add that massive interference with a system (e.g. through a “mega-miracle”) has the potential to further destabilize it – which would then mean that more miracles would be required, to keep it from falling over in the future.

Since God had no pressing reason to hurry the job of making the Earth fit for intelligent life, it would have been wiser for Him to do so incrementally.

Finally, if someone were to ask me why God couldn’t have made the earth’s organisms by a front-loading process, i.e. by programming the first living organisms with the ability to evolve into whales and other organisms without the need for any further genetic manipulation on His part, I would answer that front-loading is not just physically but mathematically impossible, given the finite information storage capacity of the cosmos, the laws of quantum physics, and Turing’s proof of the indeterminacy of feedback. See here for a brief explanation why, and see also physicist Rob Sheldon’s article, The Front-Loading Fiction. In short: given the kind of cosmos we live in, there’s no way front-loading could work.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

9. Conclusion

I have endeavored to show that there is nothing in Professor Dembski’s writings which puts Intelligent Design at odds with Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy. The objections raised by Professor Feser to certain passages in Dembski’s writings appear to stem from a mis-reading of his arguments relating to design. It is to be hoped that my efforts at demonstrating that Dembski’s writings contain nothing that an Aristotelian-Thomist would find objectionable will lead to a gradual rapprochement between Intelligent Design and Aristotelian-Thomism.