In a recent post over at Why Evolution Is True, Professor Jerry Coyne addresses what he regards as the “main incompatibility between science and religion.” Coyne is confident that science is a legitimate arbiter of truth because “there’s only one brand of science, with most scientists agreeing on what’s true,” whereas “there are tens of thousands of brands of religion, many making conflicting and incompatible claims.” In today’s short post, I’d like to explain why Coyne’s assertion about science is fundamentally mistaken.

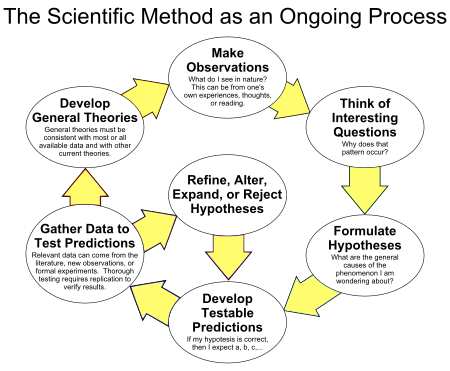

First of all, “conflicting claims” and “conflicting brands” are two very different things. At any given moment, there are literally thousands of conflicting and incompatible claims being made within each field of science. That’s part of the way science is done. Scientists call these claims hypotheses. Scientific hypotheses are continually being tested, and the vast majority of them end up being falsified or substantially modified. However, multiple conflicting claims don’t overthrow the unity of science, because scientists all agree on a single method for testing those claims: the scientific method (illustrated below, image courtesy of Professor Theodore Garland and Wikipedia). Right?

|

Wrong. As philosopher Paul Feyerabend trenchantly argued in his work, Against Method, the notion that there is a fixed scientific method is a myth:

Against Method explicitly drew the “epistemological anarchist” conclusion that there are no useful and exceptionless methodological rules governing the progress of science or the growth of knowledge. The history of science is so complex that if we insist on a general methodology which will not inhibit progress the only “rule” it will contain will be the useless suggestion: “anything goes”. In particular, logical empiricist methodologies and Popper’s Critical Rationalism would inhibit scientific progress by enforcing restrictive conditions on new theories.

(Preston, John, “Paul Feyerabend“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 Edition), edited by Edward N. Zalta.)

Professor Coyne might reply that while the scientific method evolves over the course of time, it is still something which all branches of science are more or less agreed on, at any given point in time. But this won’t do, either. Consider the sciences of cosmology, chemistry, biology, psychology and archaeology. Can anyone credibly claim that these branches of science all practice the same method? The only thing which these various disciplines could be said to share in common is that they continually generate hypotheses which can be be tested and experimentally falsified. Is falsifiability the hallmark of science, then? Alas, no: it turns out to be neither sufficient nor necessary to define science.

One problem with the falsifiability criterion is that it is far too loose: religions could also be said to generate hypotheses and discard them when they prove false. The history of the Millerite movement affords an excellent illustration of this point. In 1822, a Baptist lay preacher named William Miller became convinced that the return of Christ would take place around the year 1843. He gathered quite a following, and when 1843 passed without incident, another preacher named Samuel Sheffield Snow, who was a disciple of Miller, announced his conclusion that the Second Coming would take place on October 22, 1844, instead. Many of Miller’s followers were sadly disillusioned when this prophecy also failed to eventuate, but some formed new churches of their own, the most notable of which is the Seventh Day Adventist Church. October 22, 1844 was reinterpreted as the date when Christ entered the Holy of Holies in the heavenly sanctuary, and began his “investigative judgment” of God’s professed followers. The Second Coming will occur shortly after a “time of trouble,” when the Church will be persecuted worldwide.

Another problem with the falsifiability criterion is that not all scientists accept it, anyway. In a provocative 2014 article for Edge, theoretical physicist Sean Carroll described falsifiability as a scientific idea “ready for retirement.” Carroll argued that the virtue of any scientific theory lies in its ability to account for the data, regardless of whether the theory is empirically falsifiable or not. Carroll contended that if string theory and the theory of the multiverse are able to unify physics and account for our observations, then it makes perfect sense for scientists to accept these theories, even though we have no way of falsifying them:

In complicated situations, fortune-cookie-sized mottos like “theories should be falsifiable” are no substitute for careful thinking about how science works. Fortunately, science marches on, largely heedless of amateur philosophizing. If string theory and multiverse theories help us understand the world, they will grow in acceptance. If they prove ultimately too nebulous, or better theories come along, they will be discarded. The process might be messy, but nature is the ultimate guide.

Professor Carroll’s views remain highly controversial, and many prominent scientists vehemently disagree with them. In an article in Nature (vol. 516, pp. 321–323, 18 December 2014) titled, Scientific method: Defend the integrity of physics, physicists George Ellis and Joe Silk concur with the verdict of theoretical physicist Sabine Hossenfelder, that “post-empirical science is an oxymoron,” and they conclude that “[t]he imprimatur of science should be awarded only to a theory that is testable.” Nevertheless, it is undeniably true that over the course of time, many scientific theories end up becoming immune to falsification, simply because they come to define an entire field. It is safe to say that atomic theory will never be overturned, because it defines the field of chemistry; and evolutionists would have us believe that their theory defines the science of biology, in a similar fashion. (Of course, it doesn’t; as Dr. Jonathan Wells has pointed out, if anything defines the science of biology, it’s cell theory, which it is safe to say will never be falsified, either.)

We have seen that the view that there is a single way of doing science is a historically naive notion, which forces the various branches of science into a straitjacket and overlooks their vital differences. But there is another, deep-seated flaw associated with the “single method” view. What it ignores is that within a given branch of science, there are often profound and ongoing differences between individual scientists as to how that branch of science should be practiced. This is true not only for the arcane science of theoretical physics, but also for sciences such as biology and psychology, as well. Wikipedia lists no fewer than 40 different schools of psychology, for instance. It is very hard to see what a radical behaviorist who denies the reality of mental states has in common with a cognitive psychologist, for whom mental states play a vital explanatory role. What separates these schools of thought is not just their theories, but their whole view of what it means to be a human being. In particular, is what we call “thinking” merely a complicated piece of behavior, or is it something which we need to posit in order to explain our behavior?

The example cited above might be dismissed by people who regard psychology as a “soft” science. But nobody can deny that biology is a bona fide science. And what is becoming increasingly apparent, in the twenty-first century, is that the field of biology is fragmenting. The ongoing feud between Darwinists and adherents of Motoo Kimura’s neutral theory of evolution may perhaps be papered over. But it cannot be denied that evolutionary biologist Eugene Koonin’s appeal to “the logic of chance” and to multiverse theory, as a way of explaining “biological big bangs,” is far removed from conventional evolutionary theory. Professor James Shapiro’s concept of natural genetic engineering, which he touts as a new paradigm for understanding biological evolution, is another example of the fragmentation currently occurring within the science of biology. Dr. Michael Denton’s structuralism (an idea he borrows from the nineteenth century biologist Richard Owen), is an even more radical case in point, as it rejects historical explanations for a host of complex structures, in favor of “laws of form.” Lastly, it could be said that the Intelligent Design movement represents a fundamentally different approach to the science of biology from that favored by most scientists during the past 140 years – one in which intelligent agency plays a vital role in explaining biological systems which perform a highly specific function, but whose origin cannot plausibly be ascribed to either chance, necessity or some combination of the two.

The most that could be said for Coyne’s simplistic claim that there is “only one brand of science” is that within any branch of science, there may be long periods during which there is a “dominant paradigm” which dictates how that particular science should be practiced, and that there is a “family resemblance” between the various ways in which science is practiced, in different fields. Professor Coyne had the good fortune to grow up during a period when a single “dominant paradigm” governed the science of evolutionary biology. Now, the dominant paradigm has splintered; and perhaps Coyne would be well-advised to reconcile himself to Chairman Mao Zedong’s policy of “letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend.”

At any rate, what is beyond dispute is that Professor Coyne’s trumpeting of the methodological unity of science as a ground for making it the sole arbiter of truth can no longer be defended: it is philosophically naive, historically inaccurate and at odds with the way in which real science is done. Coyne’s diatribe against the “tens of thousands of brands of religion, many making conflicting and incompatible claims,” is equally ill-informed: almost 70% of humanity now adheres to just one of three religions (Christianity, Islam and Hinduism, which are all broadly monotheistic), and it is fair to say that the 800-million-odd adherents of folk and indigenous religions will probably be absorbed into one of these three religions (or Buddhism), with the rise of globalization. What’s more, the claims of Christianity, Islam and Judaism are certainly testable over the long-term, and all of these religions are potentially falsifiable by scientific discoveries. (I’ve previously described what would falsify my Christian faith, and the claims of Islam would be falsified if it could be shown that Muhammad was not a real person, while Judaism’s credibility depends critically on the long-term fate of the Jewish people.) In short: the claim that science occupies a uniquely privileged position as an arbiter of truth rests on a distorted view of both science and religion – and, I might add, it naively ignores the discipline of philosophy, which informs both endeavors.

What do readers think?