Kevin Padian’s review in NATURE of several recent books on the Dover trial says more about Padian and NATURE than it does about the books under review. Indeed, the review and its inclusion in NATURE are emblematic of the new low to which the scientific community has sunk in discussing ID. Bigotry, cluelessness, and misrepresentation don’t matter so long as the case against ID is made with sufficient vigor and vitriol.

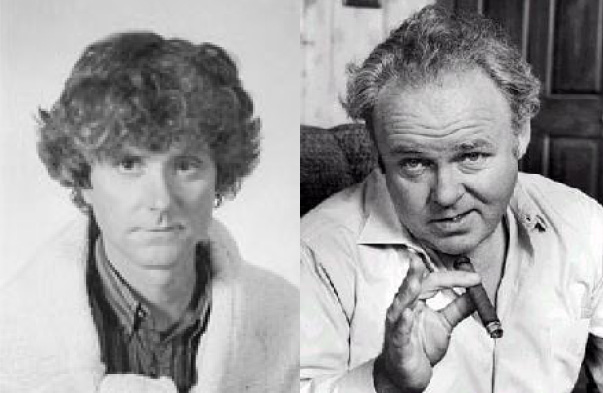

Judge Jones, who headed the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board before assuming a federal judgeship, is now a towering intellectual worthy of multiple honorary doctorates on account of his Dover decision, which he largely cribbed from the ACLU’s and NCSE’s playbook. Kevin Padian, for his yeoman’s service in the cause of defeating ID, is no doubt looking at an endowed chair at Berkeley and membership in the National Academy of Sciences. And that for a man who betrays no more sophistication in critiquing ID than Archie Bunker.

For Padian’s review, see NATURE 448, 253-254 (19 July 2007) | doi:10.1038/448253a; Published online 18 July 2007, available online here. For a response by David Tyler to Padian’s historical revisionism, go here.

One of the targets of Padian’s review is me. Here is Padian’s take on my work: “His [Dembski’s] notion of ‘specified complexity’, a probabilistic filter that allegedly allows one to tell whether an event is so impossible that it requires supernatural explanation, has never demonstrably received peer review, although its description in his popular books (such as No Free Lunch, Rowman & Littlefield, 2001) has come in for withering criticism from actual mathematicians.”

Well, actually, my work on the explanatory filter first appeared in my book THE DESIGN INFERENCE, which was a peer-reviewed monograph with Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Studies in Probability, Induction, and Decision Theory). This work was also the subject of my doctoral dissertation from the University of Illinois. So the pretense that this work was not properly vetted is nonsense.

As for “the withering criticism” of my work “from actual mathematicians,” which mathematicians does Padian have in mind? Does he mean Jeff Shallit, whose expertise is in computational number theory, not probability theory, and who, after writing up a hamfisted critique of my book NO FREE LUNCH, has explicitly notified me that he henceforth refuses to engage my subsequent technical work (see my technical papers on the mathematical foundations of ID at www.designinference.com as well as the papers at www.evolutionaryinformatics.org)? Does Padian mean Wesley Elsberry, Shallit’s sidekick, whose PhD is from the wildlife fisheries department at Texas A&M? Does Padian mean Richard Wein, whose 50,000 word response to my book NO FREE LUNCH is widely cited — Wein holds no more than a bachelors degree in statistics? Does Padian mean Elliott Sober, who is a philosopher and whose critique of my work along Bayesian lines is itself deeply problematic (for my response to Sober go here). Does he mean Thomas Schneider, who is a biologist who dabbles in information theory and not very well at that (see my “withering critique” with Bob Marks of his work on the evolution of nucleotide binding sites here). Does he mean David Wolpert, a co-discoverer of the NFL theorems? Wolpert had some nasty things to say about my book NO FREE LUNCH, but the upshot was that my ideas there were not sufficiently developed mathematically for him to critique them. But as I indicated in that book, it was about sketching an intellectual program rather than filling in the details, which would await further work (as is being done at Robert Marks’s Evolutionary Informatics Lab — www.evolutionaryinformatics.org).

The record of mathematical criticism of my work remains diffuse and unconvincing. On the flip side, there are plenty of mathematicians and mathematically competent scientists, who have found my work compelling and whose stature exceeds that of my critics:

John Lennox, who is a mathematician on the faculty of the University of Oxford and is debating Richard Dawkins in October on the topic of whether science has rendered God obsolete (see here for the debate), has this to say about my book NO FREE LUNCH: “In this important work Dembski applies to evolutionary theory the conceptual apparatus of the theory of intelligent design developed in his acclaimed book The Design Inference. He gives a penetrating critical analysis of the current attempt to underpin the neo-Darwinian synthesis by means of mathematics. Using recent information-theoretic “no free lunch” theorems, he shows in particular that evolutionary algorithms are by their very nature incapable of generating the complex specified information which lies at the heart of living systems. His results have such profound implications, not only for origin of life research and macroevolutionary theory, but also for the materialistic or naturalistic assumptions that often underlie them, that this book is essential reading for all interested in the leading edge of current thinking on the origin of information.”

Moshe Koppel, an Israeli mathematician at Bar-Ilan University, has this to say about the same book: “Dembski lays the foundations for a research project aimed at answering one of the most fundamental scientific questions of our time: what is the maximal specified complexity that can be reasonably expected to emerge (in a given time frame) with and without various design assumptions.”

Frank Tipler, who holds joint appointments in mathematics and physics at Tulane, has this to say about the book: “In No Free Lunch, William Dembski gives the most profound challenge to the Modern Synthetic Theory of Evolution since this theory was first formulated in the 1930s. I differ from Dembski on some points, mainly in ways which strengthen his conclusion.”

Paul Davies, a physicist with solid math skills, says this about my general project of detecting design: “Dembski’s attempt to quantify design, or provide mathematical criteria for design, is extremely useful. I’m concerned that the suspicion of a hidden agenda is going to prevent that sort of work from receiving the recognition it deserves. Strictly speaking, you see, science should be judged purely on the science and not on the scientist.” Apparently Padian disagrees.

Finally, Texas A&M awarded me the Trotter Prize jointly with Stuart Kauffman in 2005 for my work on design detection. The committee that recommended the award included individuals with mathematical competence. By the way, other recipients of this award include Charlie Townes, Francis Crick, Alan Guth, John Polkinghorne, Paul Davies, Robert Shapiro, Freeman Dyson, Bill Phillips, and Simon Conway Morris.

Do I expect a retraction from NATURE or an apology from Padian? I’m not holding my breath. It seems that the modus operandi of ID critics is this: Imagine what you would most like to be wrong with ID and its proponents and then simply, bald-facedly accuse ID and its proponents of being wrong in that way. It’s called wish-fulfillment. Would it help to derail ID to characterize Dembski as a mathematical klutz. Then characterize him as a mathematical klutz. As for providing evidence for that claim, don’t bother. If NATURE requires no evidence, then certainly the rest of the scientific community bears no such burden.