|

In my last post, I critiqued Dr. Sean Carroll’s claim that the existence of evil in the world renders the existence of God unlikely. In this post, I’ll be responding to skeptic John Loftus’s claim that God is a hypocrite, in his recent post, Two Unanswerable Dilemmas Concerning God and Morality.

Why Loftus believes we shouldn’t imitate God

In his first dilemma, Loftus (pictured above) summarily disposes of the notion, held by a few religious believers today, and by a small number of famous theologians in the past (notably William of Ockham), that the moral law we are obliged to follow is nothing more than a set of arbitrary decrees by God. Such a view, argues Loftus, turns God into a hypocrite, Who says to us: “Do as I say, not as I do.” Loftus then proceeds to attack what he refers to as modified divine command theories, which claim that the moral law is grounded, not in God’s arbitrary decrees, but in God’s (non-arbitrary) character, which is essentially good. Robert Merrihew Adams is the best-known exponent of this view; Paul Copan is another. The “Divine Nature theory” upheld by C. S. Lewis is substantially the same; on this subject, see Steve Lovell’s 2002 essay, C. S. Lewis and the Euthyphro Dilemma. Modified divine command theories, which emphasize God’s perfect character (or nature), sound much more reasonable than the theory that all morality is arbitrary. But Loftus objects that God’s character, judging by His indifference to people’s suffering, is a bad one, and hence not worthy of imitation by us:

God commands us to do good, to be kind, to be merciful, and seek after justice for the disenfranchised, but he doesn’t do it…

If we are to act based on God’s character then we should all be Good Samaritans. God should be a Good Samaritan…

What can justify this divine hypocrisy? 1) Creation. He’s the creator. We aren’t. So he has the right to take our lives because he made us. 2) Omniscience. He has it. We don’t. So he knows what is best. Power (or ownership) and Knowledge. This supposedly justifies why he acts differently than he commands us to act…

Loftus proceeds to give some graphic examples of suffering that God does nothing to prevent. Neither God’s position as Creator (which makes Him our owner) nor His Infinite Knowledge can possibly excuse God’s failure to act in these cases, contends Loftus:

No amount of ownership, no amount of knowledge, can ethically justify watching a man slowly roast to death in a house fire.

No amount of ownership, no amount of knowledge, can ethically justify eating popcorn while watching as a woman is beaten, gang raped, and then left for dead.

In fact, since the ethical standard is the perfect character of God (per modified divine command theories) and this God has omniscience and omnipotence, then God is even MORE obligated to alleviate suffering. For while we may not have the power or knowledge to intervene when we see intense suffering, God is not limited like us. The more that a person has the knowledge and the ability (or power) to alleviate suffering, then the more that person is morally obligated to help by intervening.

What if God has pre-existing obligations that prevent Him from intervening?

The unstated premise in this argument is that (i) lack of power (or ability) and (ii) lack of knowledge are the only things which could possibly excuse someone from failing to help another individual in distress. But I can think of an exception right away: where assisting a victim in distress would conflict with a person’s pre-existing obligations. In my post in reply to Dr. Sean Carroll on the problem of evil, I pointed out two ways that I could think of, right off the top of my head, in which these pre-existing obligations might arise. The first way would be if God ever made a promise not to continually intervene and assist people in distress, in response to an explicit request made by the human race as a whole at some point in the past, to leave them alone and let them make their own mistakes. As I wrote in my last post:

Perhaps at some point very early on in our prehistory, our rebellious ancestors grew tired of God always watching over us like the attentive parent of a young child, and said, “Enough! We don’t need a cosmic nanny protecting us from evil night and day! Leave us alone to figure it out for ourselves! Even if we have to suffer and die, we’d still prefer that to You hovering over us all the time!” And perhaps God reluctantly complied with their wishes, and promised to refrain from continually saving us. If God made such a promise, then His hands would be tied, to some degree.

Perhaps Loftus will respond that even if such a “non-intervention request” were made by our ancestors and honored by God – a highly speculative proposal for which we have no evidence – previous generations of human beings would still have no right to make decisions that bind the human race today. But I would ask him to ponder this. Having gone down that fateful path, isn’t it too late for humanity to go “back to Eden” now? We have lost our innocence. Our world is already tainted by sin, and it can only be “untainted” by a radical, earth-shattering event which brings history itself to a close.

The other way in which I could imagine a pre-existing obligation not to intervene might arise is in a situation where God had delegated the immediate responsibility for overseeing certain categories of events on Earth (and other planets) to some intelligent beings who are far more advanced than we are. Assuming that there are other intelligent life-forms in the cosmos, they’re likely to be superior to us, since we’re such a young species. (Whether we conceive of these intelligent beings as aliens or angels is immaterial here, and in any case, it’s doubtful whether we could tell the difference between angels and advanced aliens, were we ever to encounter them.) By delegating responsibilities for the day-to-day control of certain categories of events on Earth to these intelligent beings, God would be voluntarily abdicating the role of having the primary responsibility for coming to the assistance of someone in distress. It would be up to the intelligent beings to do so, as God’s deputies. As I put it in my last post:

And now suppose that some of these intelligences turned out to be either too lazy to continually keep the world’s evils in check, or too inept to do the job properly. Or suppose that some of them turned out to be positively evil characters, intent on wreaking harm. The natural world would soon become “unweeded garden” filled with “things rank and gross in nature”, as Hamlet put it. It might look utterly unlike the world God originally planned. So what’s God to do, when He sees the damage that these higher intelligences have wrought, and the suffering His lower creatures (animals and humans) have inherited as a result? Having delegated some responsibilities for overseeing creation to these higher beings, should God intervene at once and fix up the mess they’ve caused? Or should He wait a while?

Perhaps it’s obvious to John Loftus that God should intervene immediately, and correct the negligence of His lazy or wicked deputies who oversee certain classes of events on this planet. For my part, I’m not so sure about that. Supposing my hypothetical scenario to be true, I think it’s a genuinely open question whether God should act now to fix the problem caused by His deputies, or wait until a more opportune moment to intervene. My moral intuitions on this point are not clear, and I would suggest that Loftus’s moral certitude that God should intervene immediately is misplaced.

Why Loftus thinks the promise of future compensation doesn’t excuse God

Now I’d like to examine Loftus’s second dilemma, which attempts to rebut the religious view that God can compensate people in the future for present sufferings that they are undergoing:

If God can justify letting us suffer in this life by compensating us in the next life, then that ethical principle allows us to do the same thing (per modified divine command theories). We can knowingly allow people to suffer even though we could help them, so long as we compensate them afterward for our inaction.

Why can God violate these ethical principles that we are obligated to obey, if morality is based on his character? If he’s our ethical standard and acts like an inattentive and inactive monster, then why can’t we act like him? If we cannot act like him, because it would be unethical for us to do so, then God’s character is no longer the basis for morality.

All that the foregoing objection establishes is that the promise of future compensation does not, in and of itself, justify the withholding of assistance to someone in distress. But who said it did? What I would argue instead is that if God has a valid reason for withholding assistance to someone in distress at the present time, then He may (if He chooses) compensate that person for the pain that they have suffered, at some future time. However, the act of compensation per se does not make it right for God to have withheld assistance in the first place. So the question once again boils down to: can there ever be a good reason for God to withhold assistance from someone in distress?

To sum up: Loftus’s illustrations, which he invokes to great rhetorical effect in his attempt to portray God as an uncaring hypocrite for declining to come to our aid when we are in distress, all contain a hidden bias: first, they are based on “here-and-now” situations where the victim’s past is of absolutely no relevance, and second, they contain only two characters: the victim and a person standing nearby who is able to assist the victim, and who also knows how to provide assistance. In the real world, things are seldom this simple. If the victim (or the victim’s family) had explicitly declined offers of assistance from the person standing nearby on previous occasions, that could (in some cases) relieve that person of any obligation to assist the victim. And if the victim already had personal caretakers (previously appointed by the person standing nearby) who had been derelict in the performance of their duties, then it is not always clear that the person who appointed these caretakers should immediately step in to assist the victim, if the caretakers are failing to do so.

Why Loftus’s arguments are neither certain nor probable

This is not to belittle Loftus’s argument, but to put it in its proper perspective. In my first post in reply to Dr. Sean Carroll’s video, Is God a Good Theory?, I distinguished between six levels of certitude that might attach to an argument: logical certainty (which applies to truths whose denial is a contradiction in terms), self-referential certainty (which relates to truths which cannot be consistently denied by the speaker, even if they aren’t self-contradictory when set down in writing), empirical certainty (which holds for truths known from sensory experience), transcendental certainty (which attaches to truths whose denial would entail the collapse of a whole field of knowledge, such as science), abductive certainty (where the truth in question is established as overwhelmingly probable by a process of inference to the best explanation), and normative certainty (which holds for propositions established by appealing to various norms governing human rationality). None of these kinds of certainty applies to the arguments contained in the two dilemmas Loftus poses.

First, Loftus’s arguments are not watertight logical arguments. Second, they are not arguments whose conclusion would be self-referentially contradictory for an individual to deny. Third, they are not empirical arguments, whose conclusions are based entirely on sensory experience. Fourth, they are not transcendental arguments, as the denial of their conclusion does not threaten to undermine a whole branch of knowledge – e.g. ethics. Fifth, they are not arguments establishing that God’s non-existence is the best explanation of all the relevant facts, for they overlook certain highly important facts, including the beauty we find everywhere in Nature (natural evil notwithstanding), the massive amount of moral goodness in the world, and especially, the fact that we are able to discover moral truths in the first place, in addition to the moral evil which we find in the world. (Hint: “pop-psychology” sociobiological theories proposed by academics, claiming that human beings can discover moral truths by consistently adverting to “the greatest good of the greatest number” fail to explain the morality, as the utilitarian ethical standard they appeal to is fundamentally amoral: it fails to treat individuals as ends-in-themselves, and turns people into mere instruments for promoting the social good.) Sixth and finally, Loftus’s arguments are not based on any fundamental norms governing human rationality, as he appeals to none of these. Thus Loftus’s arguments do not qualify as certain, according to any of the six categories I proposed above. Of course, Loftus is perfectly welcome to propose a seventh category of objective rational certainty if he wishes to do so, but it is incumbent on him to justify the inclusion of this new category, alongside the other six.

Can we rescue Loftus’s argument by saying that its conclusion is probable, but not certain? No, for as I argued in my last post in response to Dr. Sean Carroll on the problem of evil, probability calculations have to be quantifiable. Since Loftus has not attempted to quantify the probability attaching to his premises, then we are unable to say how probable his conclusion is. (We need a ceiling and a floor estimate.)

It appears that Loftus’s argument from evil, like Dr. Sean Carroll’s, is a powerful prima facie argument against God’s existence, as it points to situations involving a victim in distress where there is a strong presumption that God, if He existed, would intervene – and yet He doesn’t. Loftus has no idea why any morally perfect God would withhold assistance to the victim, in such cases. But Loftus’s argument should be seen for what it is – an argument from incredulity. The fact that we cannot imagine a plausible explanation for some state of affairs – in this case, God’s declining to help a victim in distress – does not mean that there is no explanation. Arguments based on ignorance are not compelling – and in this case, our ignorance is massive, as we don’t know what other intelligent beings may exist in the cosmos, and we know next to nothing about humanity’s past interactions with its Creator. For us to totally disregard human history, and our place in the scheme of things, in attempting to arrive at conclusions about what God should and shouldn’t do, is monumentally silly: it represents a blinkered view of the facts. I conclude that Loftus’s two dilemmas fail to undermine the rationality of belief in a Creator.

A short note on two meanings of “Do as I do”

Loftus argues that if God’s character is to be our ethical standard, then He should set an example, so that He can say to us, “Do as I do,” and not just “Do as I say” (which would make Him a hypocrite). But what Loftus overlooks is that the injunction “Do as I do” can be understood in two different ways, referring to content and mode, respectively. First, “Do as I do” might mean: “Do the same things that I do.” Second, “Do as I do” might mean: “Do what you do in the same way that I do what I do.”

If God were to command us to “Do as I do” in the first sense, then I would certainly agree that our ethical system would collapse. But no rational Deity would ever issue such a command, as there are certain things which only the Creator of the cosmos can do, as well as other things which only the Creator should do. For us to do any of these things would be tantamount to playing God – which would be both ethically and practically disastrous.

But if God were to command us to “Do as I do” in the second sense, what might that mean? Most of the world’s religions (much maligned by Loftus) emphasize the importance of love (or compassion) in regulating one’s actions. On this understanding, for us to do as God does simply means that our acts should be motivated by love, or compassion, just as God’s actions are. In that case, we would certainly come to the aid of someone in distress, if we were able to help, unless pre-existing obligations on our part prevented us from doing so. And if we observe that God does not always help people in distress, then we are entitled to draw the conclusion that pre-existing obligations on His part – of which we know nothing – prevent Him from helping people, in some cases, if we already have solid rational grounds for inferring that there is a God.

I conclude, then, that Loftus’s charge of hypocrisy against God fails.

Some remarks on beauty

I wrote above that Loftus’s argument from evil fails to examine the totality of evidence, and I mentioned the pervasive beauty of Nature as an example of a very large fact that Loftus completely overlooks. It is the sort of striking fact which only the existence of a Transcendent Creator of the cosmos can satisfactorily account for.

In order to convey this point, I’d like to propose a test which I’ll call Torley’s Window Test. It’s very simple. Wherever you are on planet Earth, I invite you to have a look out your window and tell me: what do you see? No matter where you live, you will probably see a scene of great beauty – whether it be the natural beauty of the countryside, shown in this picture of Australia’s Barossa Valley (a leading wine-making district; image courtesy of Wikipedia)…

|

…or the man-made beauty of cities, such as Tokyo, shown here (Ginza at dusk, image courtesy of Wikipedia):

|

In neither case, if you look out your window, are you likely to see any evil. You almost certainly will not see animals (or people) suffering excruciating pain, or dying a slow and agonizing death. And you probably won’t see human beings performing depraved acts of wickedness, either. Which prompts me to ask: where is all the evil? Why is it almost nowhere to be seen? And why is beauty to be found everywhere?

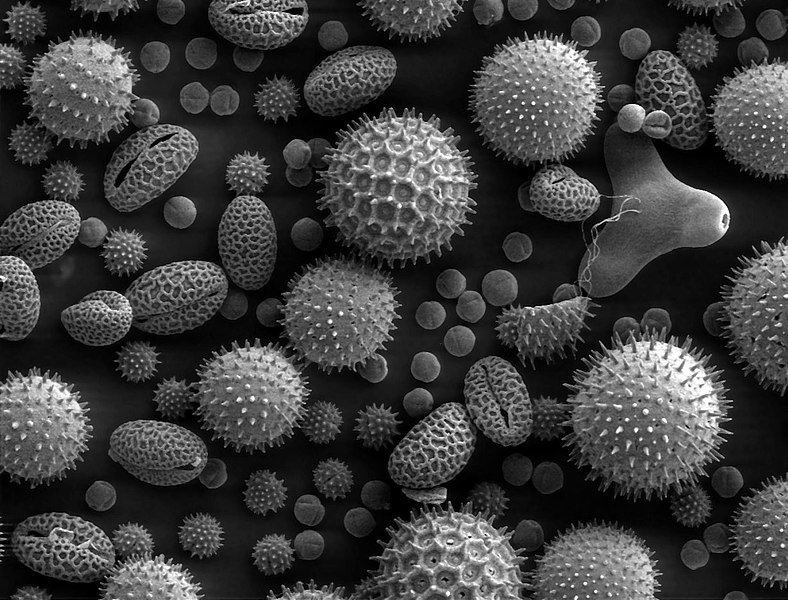

The beauty we see in Nature isn’t just confined to events occurring on the human scale of existence, either. It can also be found on the microscopic scale, as this Wikipedia image of pollen grains reveals (courtesy of Dartmouth Electron Microscope Facility, Dartmouth College):

|

Beauty is also abundant on the cosmic scale, as this image of a nebula lying within the Larger Magellanic Cloud shows:

|

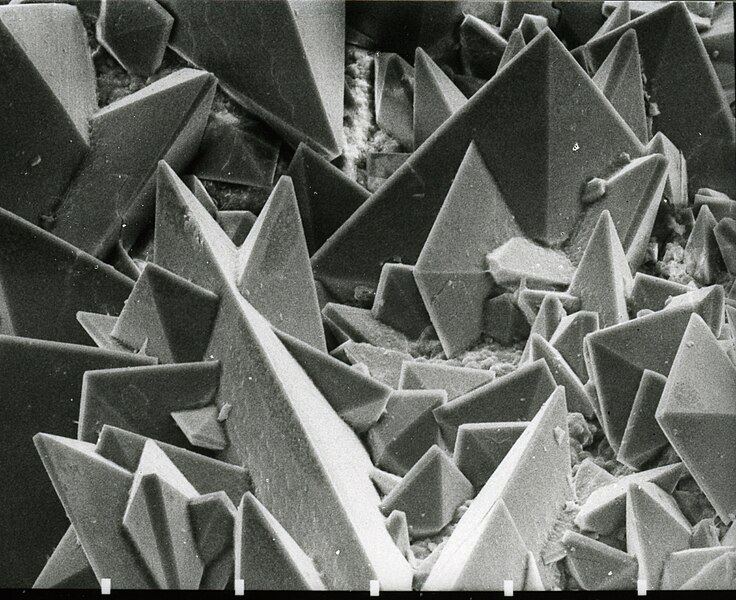

Surprisingly, beauty can even be found within the domain of natural evils. Here’s an image of a kidney stone (courtesy of E.K. Kempf and Wikipedia):

|

And here’s an image of a male lion (Panthera leo) and his cub eating a cape buffalo in Northern Sabi Sand, South Africa (photo by Luca Galuzzi; image courtesy of Wikipedia):

|

Both of the above pictures of natural evils are, at the same time, undeniably beautiful.

I would like to leave my readers with a question: if unexpected beauty (which points to the existence of a Transcendent Creator) is a pervasive feature of the cosmos, and if senseless evil (which seems to point the other way) is a local feature, confined to relatively few places on our Earth, which fact do you think should count for more, when weighing up the evidence?