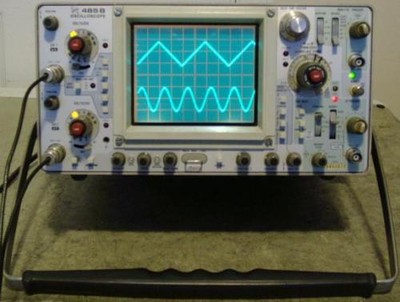

The Tektronix 465 Cathode Ray Oscilloscope is a classic of analogue oscilloscope design, one based on deflecting electron beams electrostatically to observe and measure electrical oscillations:

But, wait a minute, are we ACTUALLY seeing electron beams?

Nope, we are seeing a TRACE on the screen, where light is emitted by the phosphor as it is hit by the beams.

Wait, again: are we actually seeing the electron beams? And more particularly, the electrons in the beams?

Nope. No-one has ever actually seen that strange wavicle, the electron.

It has never been directly observed.

Never.

Because, the invisible electron is the best explanation for what we do see in the behaviour of atoms and in a world of phenomena and technologies that exploit its properties.

Indeed, there is a whole massive discipline and technology out there that is foundational to modern life and technology, Electronics.

Yes, so what?

So, we can see that science and technology — contrary to commonly held views, routinely infers to and uses explanatory constructs that are unobserved or in some cases unobservable.

Not only so, but this is a key part of scientific, inductive thinking. As in, reasoning based on cases where evidence does not provide demonstrative proof but empirical support for conclusions we accept. Which, includes reasoned inference on empirically observed traces or signs to their best causal explanation. (As we have discussed in this recent post, with deer tracks as a paradigm case.)

Why are you belabouring so obvious a point?

Because, it is apparently not so obvious to ever so many objectors to design theory.

We have been recently told by Toronto (in a remark that led to his poster child of irresponsible objections to ID status), that inference to best current explanation is in effect circular argument.

Let’s roll the tape from the just linked post, as it seems Toronto was last seen denying that this happened:

Toronto went so far wrong as to make himself a poster child for the errors we are dealing with. Citing his already linked comment at TSZ of Aug 19th, where the clip begins with a comment I made at UD:

Kairosfocus [Cf. original Post, here]: “You are refusing to address the foundational issue of how we can reasonably infer about the past we cannot observe, by working back from what causes the sort of signs that we can observe. “

[Toronto:] Here’s KF with his own version of “A concludes B” THEREFORE “B concludes A”.

Oops.

Going further, as we have seen over the course of several weeks, ID objector Critical Rationalist — flying the flag of Popper — seems to have a thing against “inductivism,” and also specifically objects to inference to best explanation, as well as the use of terms like “warrant.” Clipping:

Inductivism

– We start out with observations

– We then use those observations to devise a theory

– We then test those observations with additional observations to confirm the theory or make it more probable

However, theories do not follow from evidence. At all. Scientific theories explain the seen using the seen. And the unseen doesn’t “resemble” the seen any more than falling apples and orbiting planets resemble the curvature of space-time . . . .

Justificationism is simply impossible. But, by all means, feel free to present a “principle of induction” that actually works in practice. All I’ve seen so far is claims that “everyone knows induction works” or “everyone uses it, so it must be true”, along with common misconceptions, which doesn’t refute Popper’s criticism.

Show me how you can justify whatever it is you use to justify something, etc.

The trick in that is the strawman caricature: “We then test those observations with additional observations to confirm the theory or make it more probable.”

What happens is that, first, ever since Newton in Opticks, Query 31, in 1704, scientific reasoning has been far more nuanced and complex than that.

Induction — as has been repeatedly pointed out but too often ignored — is an approach to reasoning where evidence provides support for conclusions, not demonstrative proof beyond doubt. In some cases — cf statistical reasoning — we may be able to provide a numerical probability score. In others — e.g. the inductions that the sun is likely to rise tomorrow, or that we often make errors in reasoning — no probability number is assigned, but the conclusion is morally certain. (That is, one would be irresponsible or foolish to ignore it or act as though it were false.)

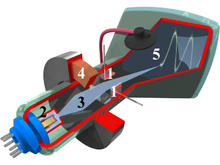

In other cases, we construct hypotheses that seem to explain — make good sense of — patterns of observations. We test them, and find that they are reliable in some cases, i.e. they unify our current base of observations and accurately predict new ones. They may even be potentially true, i.e. they are not self-contradictory and they are not outrageously false like the “transistor man” model used to introduce circuit modelling in electronics. (NB: Without loading issues, the gain of cascaded stages is a product G1 G2 G3, not a sum.)

In science, we routinely are inclined to accept such models as provisional knowledge — warranted, credible albeit subject to correction in light of further evidence and reason.

Why?

Because, we live in a world that is overwhelmingly dominated by uniformities, ranging from the regular rising of the sun to the pattern that even many chance processes follow patterns that lead to distributions such as the binomial distribution, the Gaussian or the Weibull. So, if we evidently are identifying such a pattern, it makes sense to accept it as such, subject to correction as we may make mistakes or there may be extreme cases where the pattern breaks down. And, because in such inferences, the direction of logical implication, IF (Explanation) THEN (Observations) runs in the opposite direction to the direction of empirical support. If P then Q, Q, so P is a fallacy, rooted in confusing implication with equivalence.

So, is science fallacious and foolish?

I guess, first, it is a sign of where things have reached, when design theorists or thinkers or supporters of such have to be defending basic principles and methods of science and scientific reasoning from anti-design objectors!

No, science is not fallacious, once we recognise the pattern of uniformities, so it is inherently reasonable to look for such and to — having provided reasonable tests — accept that something like Kepler’s laws do summarise empirical observations, and that something like Newtonian dynamics provides a framework that makes sense of those laws of observed motion. And where we recognise that such a conclusion is provisional and subject to correction. Where also, it is reasonable to look at live option alternatives and hold a competition over factual adequacy, coherence and explanatory power and simplicity. An explanatory model that has stood such tests will at minimum be empirically reliable over a reasonable range, and so it is wise to pay attention to it, without allowing it to become a blinding ideology.

Gotcha, design theory does not pass such tests!

In fact, it does.

We live in a world where functionally specific complex organisation and associated information — FSCO/I — is a commonplace. This post is an example, Computer technology, the public library, etc etc etc, too. In all these cases of observed cause, FSCO/I is caused by intelligently directed organising work (IDOW). Design.

A reliable pattern.

And, a sign that points to a material causal factor.

Open to test, and successful on billions of test cases. With no serious counter-examples.

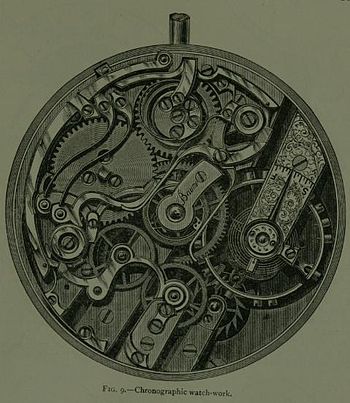

For instance the objector who — some years ago, attempting to turn about Paley’s watch arguments (nb the second one on a self-replicating watch) — posted a YouTube video on how gears and rods could somehow evolve into clocks, has not understood just what it takes to make a real watch movement using a gear train or backing plates etc that correctly mount such precision machinery to fulfill a task.

The watch evolution fiasco ends up actually corroborating the point.

(By contrast, the proposed neo-Darwinian mechanisms of body-plan level macro-evolution and its various supplements, has never been seen to happen in our observation. What we have is a massive extrapolation from observed small scale adaptations to the suggested innovation of major body plan features on incremental chance variation and differential reproductive success in ecological niches. Assumed true by massive extrapolation, not based on actual observation. Where also, the empirically well supported FSCO/I source is in IDOW principle says, not so fast. Which is part of why there is such a controversy over what would otherwise be ho-hum.)

So then, when we see Popper talking of how theories that have been tested and are found reliable are corroborated, we have good reason to say, yes. Precisely.

That is, we have good reason to infer that we have a reliable pattern in hand, though one subject to correction in light of further discoveries and/or reasoned analysis.

So, why not simply accept that? As well, as that at least some such corroborated best current explanations are morally certain and others are sufficiently amenable to analysis that we can assign them probabilities on statistical studies. Yeah, that’s not proof beyond reasonable doubt or future correction.

But then, one of the things which are certain, is that to err is human.

So, why not simply accept Newton’s remark on such inferred general patterns, in Opticks, Query 31:

. . . although the arguing from Experiments and Observations by Induction be no Demonstration of general Conclusions; yet it is the best way of arguing which the Nature of Things admits of, and may be looked upon as so much the stronger, by how much the Induction is more general. And if no Exception occur from Phaenomena, the Conclusion may be pronounced generally. But if at any time afterwards any Exception shall occur from Experiments, it may then begin to be pronounced with such Exceptions as occur.

That seems to be how modern science has progressed in recent centuries, and it seems to be a good rule of thumb for general common sense reasoning too. So, all we need to do is to update Newton on the nature of induction, broadening our understanding to explicitly include that it is the logical argument form that infers that certain evidence supports and may warrant (provisionally) a conclusion, sometimes to moral certainty.

This includes inference to best explanation.

And so, it seems we are now at the point where design thinkers are having to defend basic logical principles routinely used in scientific work, from objectors to design theory.

Looks like the tide of the hot and furious debate over design is beginning to turn. END