|

|

It is not often that one’s opinion of a book improves after reading three negative reviews of it. I haven’t yet read Professor Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False, but after reading what biologist H. Allen Orr, philosophers Brian Leiter and Michael Weisberg, and philosopher and ID critic Elliott Sober had to say about the book, I came away convinced that neo-Darwinism is an intellectual edifice resting on a foundation of sand… and sheer intellectual stubbornness on the part of its adherents. I do not wish to question the sincerity and learning of the reviewers, but I was deeply shocked by their unshakable attachment to Darwinism. Reading through the reviews, I was astonished to find the authors arguing that even if the origin of life should prove to be a fantastically improbable event that would not be expected to happen even once in the entire history of the cosmos, even if scientists are utterly unable to predict the general course of evolution, even if all attempts to reduce the science of biology to physics and chemistry are doomed to failure, even if it can be shown that we will never be able to explain consciousness in terms of physical processes, and even if neo-Darwinism proves to be incompatible with the existence of objective moral truths, such as “Killing people for fun is wrong,” we should still prefer Darwinism to any other account of origins, for to do otherwise is unscientific. I have to ask: whence such madness?

What these reviewers apparently fail to realize is that Charles Darwin himself would have conceded none of the “even ifs” conceded by his latter-day disciples. He realized, as they do not, that doing so would have severely undermined the credibility of his theory. Darwin believed in, and convinced his contemporaries of, the superiority of his theory of evolution by natural selection, largely because it claimed to provide an account of the development of life on Earth that was both predictable and progressive, and because it purported to explain the emergence of consciousness and our mental faculties in terms of underlying bodily processes. Interestingly, Darwin somehow managed to combine his thoroughly deterministic worldview with a belief in the objectivity of certain moral truths: throughout his life, he steadfastly maintained that slavery is wrong.

For the benefit of readers who may be wondering about Nagel’s account, I should say that he advocates a form of naturalistic teleology: that is, he believes that a purely historical explanation of the origin of life, consciousness and intelligence is doomed to failure; so, too, is a reductive explanation of these phenomena. We have to invoke final causes. Nagel is not religious; he does not believe that anything exists outside the natural realm. Nevertheless, he believes that it is a brute fact about Nature that it is biased towards the generation of life and consciousness. Because neo-Darwinism is an historical account of origins, which shuns forward-looking final causes and explains life within a reductionist framework, Nagel thinks it is almost certainly wrong – or at least, incomplete.

Professor Nagel’s espousal of teleological naturalism in his book, Mind and Cosmos has attracted a lot of criticism. In this essay, I’d like to address the main criticisms, one by one. My essay is divided into nine parts. Throughout this essay, all green highlights are mine.

1. Does the neo-Darwinian theory of evolution need to make predictions about the future, in order to qualify as a good scientific theory?

|

In his book, Mind and Cosmos, Professor Thomas Nagel argues that any evolutionary theory worth its salt should be able to retrospectively predict key events in the history of life (such as the emergence of consciousness) and show why these events were likely to occur. In their review of Nagel’s book, Professor Brian Leiter and Associate Professor Michael Weisberg attempt to rebut Thomas Nagel’s argument by insisting that a good scientific explanation does not need to make any predictions – a contentious claim that we’ll examine below. What I would like to do first is ask a simple question: what did Charles Darwin think about the role of prediction in scientific explanation?

(a) Darwin: a good scientific explanation has to invoke laws and be capable of making predictions

In his 1838 Essay on Theology and Natural Selection, Darwin insisted that any good scientific explanation had to be capable of making predictions – which is precisely what led him to reject creationism in the first place. Since the will of God is not subject to any law, it is unpredictable. For this reason, Darwin regarded theological explanations of biological diversity as scientifically useless:

N.B. The explanation of types of structure in classes – as resulting from the will of the deity, to create animals on certain plans, – is no explanation – it has not the character of a physical law /& is therefore utterly useless. – it foretells nothing / because we know nothing of the will of the Deity, how it acts & whether constant or inconstant like that of man. – the cause given we know not the effect.

(Italics Darwin’s, bold emphases mine – VJT.)

What’s more, Darwin believed that any explanation of a phenomenon in terms of physical laws had to be a deterministic explanation: as he put it in his Autobiography, “Everything in nature is the result of fixed laws.” (Page 87, Nora Barlow’s 1958 edition.)

(b) According to Darwin, evolution is a deterministic process, whose broad trends are predictable over time

Darwin applied these rigorous methodological standards to his own theory: he envisaged evolution by natural selection as a thoroughly deterministic process, at least in its general outcomes. In his magnum opus, The Origin of Species, Darwin insisted that the current laws of Nature were sufficient to account for the origin of species, by natural processes:

If then the geological record be as imperfect as I believe it to be, and it may at least be asserted that the record cannot be proved to be much more perfect, the main objections to the theory of natural selection are greatly diminished or disappear. On the other hand, all the chief laws of palaeontology plainly proclaim, as it seems to me, that species have been produced by ordinary generation: old forms having been supplanted by new and improved forms of life, produced by the laws of variation still acting round us, and preserved by Natural Selection.

(The Origin of Species, 1st edition, 1859, Chapter X, p. 345.)

For Darwin, the course of evolution was not only fixed by deterministic laws; it was also predictable, at least in its broad outline. Darwin maintained that over the course of time, evolution tended to produce organisms that were more and more complex, in the degree of specialization of their body parts. In the concluding chapter to The Origin of Species, he argued that the evolution of life, viewed as a whole, was guaranteed by the laws of Nature to progress ever upward, and that the evolution of the “higher animals” was the inevitable outcome of simple biological laws:

And as natural selection works solely by and for the good of each being, all corporeal and mental endowments will tend to progress towards perfection. It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with Reproduction; Inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect and direct action of the external conditions of life, and from use and disuse; a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of less-improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows.

(1st edition, 1859, Chapter XIV, pp. 489-490.)

A critic might object that terms such as “progress,” “perfection,” “improved” and “higher” are scientifically vague, making them of little predictive value. However, Darwin was fully cognizant of this objection, and in his Descent of Man, he attempted to provide a rigorous definition of evolutionary progress:

The best definition of advancement or progress in the organic scale ever given, is that by Von Baer; and this rests on the amount of differentiation and specialisation of the several parts of the same being, when arrived, as I should be inclined to add, at maturity. Now as organisms have become slowly adapted by means of natural selection for diversified lines of life, their parts will have become, from the advantage gained by the division of physiological labour, more and more differentiated and specialised for various functions. The same part appears often to have been modified first for one purpose, and then long afterwards for some other and quite distinct purpose; and thus all the parts are rendered more and more complex. But each organism will still retain the general type of structure of the progenitor from which it was aboriginally derived. In accordance with this view it seems, if we turn to geological evidence, that organisation on the whole has advanced throughout the world by slow and interrupted steps.

(1st edition, 1871, Chapter VI, p. 211.)

On the Darwinian account, the evolution of animals’ body parts over the course of time is ultimately determined by the successive requirements imposed on them, as a result of changes in their environment, to which their ancestors had to adapt. The cumulative – and entirely predictable – result of such changes was the differentiation and specialization of living things’ bodily organs. The appearance of highly developed animals was thus the predictable outcome of simple biological laws operating over a period of billions of years.

(c) Leiter and Weisberg’s bold claim: a good scientific explanation doesn’t need to make any predictions

So it was with some surprise that I read Professor Brian Leiter and Associate Professor Michael Weisberg arguing in their review that a good scientific explanation does not need to make any predictions – even retrospective ones! For Leiter and Weisberg, the demand that scientific explanations should be able to make predictions is fundamentally misconceived:

Nagel endorses the idea that explanation and prediction are symmetrical: “An explanation must show why it was likely that an event of that type occurred.” In other words, to explain something is to be in a position to have predicted it if we could go back in time. He also writes, “To explain consciousness, a physical evolutionary history would have to show why it was likely that organisms of the kind that have consciousness would arise.” Indeed, he goes further, claiming that “the propensity for the development of organisms with a subjective point of view must have been there from the beginning.”

This idea, however, is inconsistent with the most plausible views about prediction and explanation, in both philosophy and science.

As we have seen, Darwin would have disagreed with this analysis: it was his dissatisfaction with the unpredictability of creation by Divine fiat that led him to search for a naturalistic alternative, and in the final paragraph of his Origin of Species, he declared that the evolution of the higher animals “directly follows” from the workings of the laws of Nature. In conceding the inability of the modern theory of evolution to make predictions about the future, Leiter and Weisberg are unknowingly depriving Darwin’s theory of one of its major selling points.

In any case, a careful reading of Leiter and Weisberg’s review leads me to conclude that their differences with Professor Thomas Nagel over the nature of scientific explanations are more apparent than real. What Leiter and Weisberg are denying is the need for scientific explanations to predict individual events, or to make predictions with certainty. Nagel could happily grant both these points. What he would deny, if I read him aright, is the possibility of a scientific explanation which doesn’t even make generic, probabilistic predictions. The theory of evolution must at least do that.

(d) Why probabilistic explanations don’t eliminate the need for predictions

Leiter and Weisberg attempt to bolster their claim that good scientific theories don’t need to be predictive, by an appeal to probabilistic reasoning:

Philosophers of science have long argued that explanation and prediction cannot be fully symmetrical, given the importance of probabilities in explaining natural phenomena. Moreover, we are often in a position to understand the causes of an event, but without knowing enough detail to have predicted it. For example, approximately 1 percent of children born to women over 40 have Down syndrome. This fact is a perfectly adequate explanation of why a particular child has Down syndrome, but it does not mean we could have predicted that this particular child would develop it.

But this argument fails to undermine Professor Nagel’s case. Even in the passage quoted by Leiter and Weisberg earlier, Nagel does not defend the extreme view that individual events are only properly explained when they can be predicted from their individual causes – which is why the Down syndrome example the authors cite completely misses the point. For Nagel, scientific explanation occurs at the generic level of the type rather than the individual token: as he puts it, “An explanation must show why it was likely that an event of that type occurred.” The perceptive reader will also notice that Nagel says “likely” rather than “certain.” Nagel is not espousing a rigid determinism here; he is merely insisting that a good explanation of consciousness must show that there was a significant likelihood of it emerging somewhere in the cosmos, over the course of time. Hardly an unreasonable request, one would have thought. For the past few decades, however, neo-Darwinists have lowered the bar: instead of demonstrating that life or consciousness had a mathematical likelihood of arising somewhere, they have been content to argue that life and consciousness may have arisen somewhere, because no law of Nature prohibits them from doing so. The trouble with explanations of this kind is that a scientific theory’s being able to explain the mere possibility of a specific effect does not make it a good theory. Unless that theory can assign a certain probability to that effect occurring within the time available, it is impossible to compare the theory with other scientific theories, in order to see which one does a better job of explaining the effect.

We might summarize this point under the slogan: “No quantification, no science.” At the present time, Darwin’s theory is poor at quantification, for all except the most trivial biological changes. When it comes to large-scale changes such as the emergence of consciousness, or even the formation of feathers or flagella, the hard numbers simply aren’t there: biologists have no probabilities to guide them – just guesswork.

2. Is Darwinism tied to reductionism?

|

Professor Richard Dawkins, an ardent defender of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Like Darwin, Dawkins is an out-and-out reductionist. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

(a) Leiter and Weisberg’s astonishing claim: Darwin’s theory of evolution isn’t reductionist

In their review of Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos, Professors Leiter and Weisberg also make the astonishing claim that Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is not committed in any way to reductionistic account of life or consciousness:

Nagel opposes two main components of the “materialist” view inspired by Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. The first is what we will call theoretical reductionism, the view that there is an order of priority among the sciences, with all theories ultimately derivable from physics and all phenomena ultimately explicable in physical terms. We believe, along with most philosophers, that Nagel is right to reject theoretical reductionism, because the sciences have not progressed in a way consistent with it. We have not witnessed the reduction of psychology to biology, biology to chemistry, and chemistry to physics, but rather the proliferation of fields like neuroscience and evolutionary biology that explain psychological and biological phenomena in terms unrecognizable by physics. As the philosopher of biology Philip Kitcher pointed out some thirty years ago, even classical genetics has not been fully reduced to molecular genetics, and that reduction would have been wholly within one field. We simply do not see any serious attempts to reduce all the “higher” sciences to the laws of physics.

Yet Nagel argues in his book as if this kind of reductive materialism really were driving the scientific community…

Nagel here aligns himself, as best we can tell, with the majority view among both philosophers and practicing scientists. Just to take one obvious example, very little of the actual work in biology inspired by Darwin depends on reductive materialism of this sort; evolutionary explanations do not typically appeal to Newton’s laws or general relativity. Given this general consensus (the rhetoric of some popular science writing by Weinberg and others aside), it is puzzling that Nagel thinks he needs to bother attacking theoretical reductionism.

Leiter and Weisberg claim to speak for practicing scientists as well as philosophers, and they make the further claim that Darwinian biology doesn’t depend on reductionism. Both claims are highly contentious, to say the least.

(b) What Darwin’s leading defenders think about reductionism

The first thing that astonished me about this passage was that Professor Leiter and Weisberg were so ready – indeed, eager – to concede the failure of reductionism. Hardly any scientist or philosopher believes it nowadays, they claimed. This would definitely be news to Darwin’s modern-day bulldog, Professor Richard Dawkins, who has forcefully argued that all genuinely scientific explanations have to be reductive. On Dawkins’ view, a good explanation is one which simplifies that which it attempts to explain. To reject reductionism, on Dawkins’ view, is equivalent to saying that the complexity of life cannot be simplified. For Dawkins, that’s an admission of defeat. As he put it in an interview with Nick Pollard on February 28, 1995, which was published in the April 1995 edition of Third Way (vol 18 no. 3):

The whole scientific enterprise is aimed at explaining the world in terms of simple principles. We live in a world which is breathtakingly complicated, and we have a scientific theory – we have several – which enables us to see how that world could have come into being from very simple beginnings.

That’s what I call understanding. If I want to understand how a machine works, I want an explanation in terms of sub-units and even smaller sub-units, and finally I would get down to fundamental particles. That’s the kind of explanation which science aspires to give and is well on the way to giving.

… Reductionist explanations are true explanations.

You really feel you’ve understood how a motor car works if you’ve been told how each of its bits work and how the bits move together to make the car work. Then you feel you’ve really got somewhere. But if somebody tried to explain the car in terms of – well, Julian Huxley satirised it as explaining a railway train by force locomotive – you would feel you had understood absolutely nothing.

But, it will be said, Dawkins is just one biologist. Very well, then; let us look at what another leading Darwin defender, Professor Jerry Coyne (author of the best-seller, Why Evolution is True) had to say about reductionism, in a recent post entitled, Is reductionism wrong?: a philosopher weighs in. Coyne composed this post in response to an opinion piece, entitled, Anything but Human (New York Times, August 5, 2012) by philosopher Richard Polt, professor and chair of philosophy at Xavier University, who criticized what he saw as the increasingly prevalent reductionist view that the human brain is basically a computer. In his reply, Coyne defended not only the brain-as-computer metaphor, but also the reductionist view that all of the emergent properties of any entity can, in principle, be reduced to the interaction of its parts:

Given that our brains evolved, why shouldn’t we assume that thinking and perceiving are essentially information processing. Yes, it’s a complicated form of processes, but what else could it be. And maybe now we can’t understand the whole in terms of its parts, and maybe aspects of our mentality, like consciousness, are emergent properties, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t ultimately, or in principle, be reduced to the interaction of parts. As far as we know, in all sciences emergent properties, like the behavior of gases or fluids, must be consistent with lower-level properties. There are no “top-down” properties that are not consistent with the interaction of parts.

I suspect that there are many modern biologists who would share Dawkins’ and Coyne’s views on reductionism. I therefore disagree with Leiter and Weisberg’s confident assertion that there is a “general consensus” in the scientific community that reductionism is false. I would like to ask: where is their evidence?

There is much that could be said in reply to Dawkins’ argument for reductionism. All I will say here is that scientific explanations need not involve a multi-level hierarchy of organization: sometimes, they invoke a single-level network of interacting, inter-dependent components. (Ecosystems are one case that immediately springs to mind; geological cycles are another.) Reductionism, then, is not essential to a good scientific explanation. On this point, Nagel is surely right.

Coyne’s argument is also flawed, because it trades on an equivocation. It is one thing to say that all of the “top-down” properties of an entity must be consistent with the interaction of its parts. It is quite another thing to say that the “top-down” properties of an entity must be determined by the interaction of its parts, as Coyne maintains. Only the second claim is reductionistic.

To illustrate the difference between the two claims, I’d like to give an example relating to free will. (I’m talking about libertarian free will here, which is what ordinary folk usually mean by the term.) Suppose that at the subatomic level, events occurring in our brains are subject to quantum effects, and that these effects are non-deterministic. It is easy to show that a non-deterministic system may be subject to specific constraints, while still remaining random. These constraints may be imposed externally, or alternatively, they may be imposed from above, as in top-down causation. To see how this might work, suppose that my brain performs the high-level act of making a choice, and that this act imposes a constraint on the quantum micro-states of tiny particles in my brain. This doesn’t violate quantum randomness, because a selection can be non-random at the macro level, but random at the micro level. The following two rows of digits will serve to illustrate my point.

1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1

0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1

The above two rows of digits were created by a random number generator. The digits in some of these columns add up to 0; some add up to 1; and some add up to 2.

Now suppose that I impose the non-random macro requirement: keep the columns whose sum equals 1, and discard the rest. I now have:

1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1

0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0

Each row is still random (at the micro level), but I have now imposed a non-random macro-level constraint on the system as a whole (at the macro level). That, I would suggest, what happens when I make a choice. Non-determinism, by itself, does not make us free in the libertarian sense; but top-down causation, acting on a non-deterministic system, makes genuine libertarian free will possible.

In this example, the entity in question is the human brain. The holistic “top-down” properties of the brain are quite consistent with the interaction of its non-deterministic subatomic parts; but they are not determined by the interaction of those parts: on the contrary, it is the whole that determines the parts, while preserving their randomness. Coyne’s argument fails to rule out holism; all it establishes is the rather trivial point that the activity of wholes is constrained (but not necessarily determined) by their parts.

(c) Was Charles Darwin a reductionist?

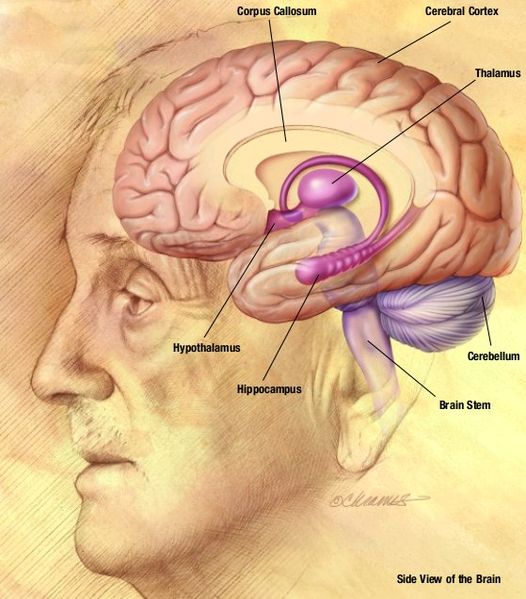

|

Charles Darwin shared the belief of the French physiologist Pierre Cabanis (1757-1808) that the human brain secretes thought just as the liver secretes bile.

Drawing of the human brain, showing several of the most important brain structures.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The second thing that struck me about the above passage by Professors Leiter and Weisberg was that the authors were blissfully unaware that they were arguing against the views of Charles Darwin himself. Darwin’s account of the human mind was thoroughly mechanistic and reductionistic. In his Notebook C: Transmutation of species (2-7.1838), he wrote:

Why is thought, being a secretion of brain, more wonderful than gravity a property of matter? – It is our arrogance, it our admiration of ourselves. (Paragraph 166)

Darwin’s assertion here that thought is “a secretion of brain” echoes a famous remark by the French physiologist Pierre Jean Georges Cabanis (1757-1808), who wrote in his Rapports du physique et du moral de l’homme (1802) that “to have an accurate idea of the operations from which thought results, it is necessary to consider the brain as a special organ designed especially to produce it, as the stomach and the intestines are designed to operate the digestion, (and) the liver to filter bile…” (English translation, On the Relation Between the Physical and Moral Aspects of Man by Pierre-Jean-George Cabanis, edited by George Mora, translated by Margaret Duggan Saidi from the second edition, reviewed, corrected and enlarged by the author, 1805. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1981, p. 116). This remark is usually cited as the pithy maxim: “The brain secretes thought as the liver secretes bile.”

I haven’t finished with Darwin yet. There’s a rather jumbled passage in his Old and Useless Notes about the moral sense & some metaphysical points (1838-1840), in which the young Darwin suggests that consciousness can be explained as the joint product of sensation and memory:

Sensation of higher order where the sensation is conveyed over whole body (which it may be in first case as when the excised heart is pricked) and certain actions (only evidence where not consciousness) are produced in consequence having some relation to the primary sensation – man moving leg when asleep (or habitual actions) – perhaps polypi – (so that lower animals are sleeping higher animals & not plants as supposed by Buffon) Consciousness is sensation No. 2. with memory added to it, man in sleep not conscious, nor child— Evidence of consciousness, movements /?/ anterior to any direct sensation, in order to avoid it – beetles feigning death upon seeing object, – are Planariae conscious. –

(Old & useless notes about the moral sense & some metaphysical points. (1838-1840), Page 9.)

A later passage in the same notebook, written in Darwin’s personal handwriting after a three-page interpolation by another author (possibly Hensleigh Wedgwood), is even more explicit about the possibility of explaining the subjective aspect of consciousness in causal terms:

[We see a particle move one to another, & (or conceive it) & that is all we know of attraction. but we cannot see an atom think: they are as incongruous as blue & weight: all that can be said that thought & organization run in a parallel series, if blueness & weight always went together, & as a thing grew blue it /uniquely/ grew heavier yet it could not be said that the blueness caused the weight, anymore than weight the blueness, still less between action things so different as action thought & organization: But if the weight never came until the blueness had a certain intensity (& the experiment was varied) then might it now be said, that blueness caused weight, because both due to some common cause:- The argument reduced itself to what is cause & effect: it merely is /invariable/ priority of one to other: no not only thus, for if day was first, we should not think night an effect]CD

(Old & useless notes about the moral sense & some metaphysical points. (1838-1840), Page 41 v.)

Here, Darwin displays some hesitation as to the metaphysical question of precisely what makes one event a cause of another. But he is quite confident that once we can isolate the causal antecedents of conscious thought, we have successfully explained it. There’s no doubt about it; Darwin was an out-and-out reductionist.

In their eagerness to divorce the theory of evolution by natural selection from any links to reductionism, Leiter and Weisberg have left us with a watered-down theory that is no longer recognizably Darwinian. One wonders what Charles Darwin would make of it, were he alive today.

(d) Orr: a reductionist materialist account of mind might still be true, even if we’re too stupid to comprehend it

|

A Big eared townsend bat, (Corynorhinus townsendii). Philosopher Thomas Nagel is the author of a now-famous paper, What is it like to be a bat?, in which he criticized the reductionist program, and argued that current attempts to explain the subjectivity of consciousness in objective terms had failed. Image courtesy of US government and Wikipedia.

In his review of Professor Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos, biologist Allen Orr concedes that Nagel has made an excellent philosophical case against the possibility of explaining consciousness, which is inherently subjective, in objective scientific terminology, as materialists have attempted to do. However, Orr does not conclude that materialism is false; following philosopher Colin McGinn, he suggests that a materialist account of mind may be true, but that the human mind is too limited to grasp how it would work:

… I can’t go so far as to conclude that mind poses some insurmountable barrier to materialism. There are two reasons. The first is, frankly, more a sociological observation than an actual argument. Science has, since the seventeenth century, proved remarkably adept at incorporating initially alien ideas (like electromagnetic fields) into its thinking. Yet most people, apparently including Nagel, find the resulting science sufficiently materialist. The unusual way in which physicists understand the weirdness of quantum mechanics might be especially instructive as a crude template for how the consciousness story could play out. Physicists describe quantum mechanics by writing equations. The fact that no one, including them, can quite intuit the meaning of these equations is often deemed beside the point. The solution is the equation. One can imagine a similar course for consciousness research: the solution is X, whether you can intuit X or not. Indeed the fact that you can’t intuit X might say more about you than it does about consciousness.

And this brings me to the second reason. For there might be perfectly good reasons why you can’t imagine a solution to the problem of consciousness. As the philosopher Colin McGinn has emphasized, your very inability to imagine a solution might reflect your cognitive limitations as an evolved creature. The point is that we have no reason to believe that we, as organisms whose brains are evolved and finite, can fathom the answer to every question that we can ask. All other species have cognitive limitations, why not us? So even if matter does give rise to mind, we might not be able to understand how.

Regarding Professor Orr’s first suggestion, I should point out that the example he offers does not help his case. Quantum mechanics is mysterious, but it is nevertheless capable of being described in mathematical terms. The properties that it describes are thus measurable; they are objective, and can be characterized in third-person terminology. Some versions of quantum theory insist that a conscious observer is needed to collapse the wave-function, but on other accounts, even a measuring device can count as an observer; and in any case, the observations made are publicly shareable. Human and animal consciousness, by contrast, has an ineluctably private and subjective aspect to it, which resists quantification and scientific measurement.

Orr’s second point, that consciousness might be explicable in materialistic terms but that we might not be able to grasp how, is irrefutable on its own terms. But what it overlooks is that in order for Darwinism to be a rationally persuasive account of life, it must appear to us as being capable (at least in principle) of explaining every aspect of life on Earth – including consciousness. If there are sound philosophical reasons showing that human beings will never be able to explain consciousness in Darwinian terms, then we need to confront the question: should the intractability of the problem of consciousness count against Darwin’s theory? Should we reject it for that reason? What Orr is essentially saying is that we shouldn’t: but in so doing, he is implicitly appealing to a “God’s eye” view of Nature. The human mind, he says, is congenitally incapable of grasping itself; but a greater mind than our own (say, that of a Martian) might be able to grasp ours. But of course, it would be unable to grasp its own mind, and would therefore be unable to provide a complete and satisfying account of its own evolution. The same problem besets any other intelligent being within the natural world. Only an eternal, supernatural Deity Whose Mind had never evolved could possibly grasp the “big picture.”

But since Orr does not intend to argue for the existence of God, what he is therefore committed to saying is that we should believe in Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, even though we know that for us, and indeed, for any intelligent life-form, no matter how technologically advanced it may be, any evolutionary account of origins that it comes up with will necessarily be incomplete. If Darwinism is true, then there is one thing about life that a sapient life-form will be forever unable to explain: its own capacity for conscious thought. The irony here is that Charles Darwin himself would have disowned this shocking and somewhat Godelian conclusion. The reason why he put forward his theory of evolution in the first place was in order to provide a complete and overarching explanation of every facet of life.

3. Does the plausibility of Darwinism depend on the origin of life and the emergence of consciousness and intelligence being unsurprising occurrences?

In his book, Mind and Cosmos, Professor Thomas Nagel argues that any adequate explanation of the origins of life, intelligence, and consciousness must show that those events had a significant likelihood of happening, rendering their occurrence unsurprising. He is in good company here: Charles Darwin was of the same view.

(a) Darwin regarded the origin of life as a “not improbable” occurrence

|

|

A Gram-negative bacterial flagellum. The base drives the rotation of the hook and filament. Image courtesy of LadyofHats and Wikipedia.

Darwin wisely refused to speculate regarding the exact process by which life had originated: his “warm little pond” example in his letter to Joseph Hooker (February 1st, 1871) was intended purely for the purposes of illustration. Nevertheless, throughout his life, Darwin upheld the view that the origin of life would one day be shown to be an unsurprising occurrence, which could be explained by the simple laws of chemistry.

Writing in his Second Notebook in 1837, twenty-two years before the publication of The Origin of Species, Darwin recorded his serene conviction that “The intimate relation of Life with laws of chemical combination, & the universality of latter render spontaneous generation not improbable.” (Notebook C [Transmutation of species (1838.02-1838.07)], page 102e.) And towards the end of his life, in his February 28, 1882 letter to D. Mackintosh (Letter 13711, Cambridge University Library, DAR.146:335, not yet available online), he wrote that despite the absence of any evidence for a living being developing from inorganic matter, “I cannot avoid believing the possibility of this will be proved some day in accordance with the law of continuity.” (For further references, see Charles Darwin and the Origin of Life by Juli Pereto, Jeffrey L. Bada, and Antonio Lazcano, in Origins of Life and Evolution of the Biosphere, 2009 October; 39(5): 395-406, doi: 10.1007/s11084-009-9172-7.)

(b) Why Darwin regarded the emergence of consciousness as an unsurprising fact

We have already seen that Darwin referred to thought as “a secretion of brain” in his Notebook C: Transmutation of species (2-7.1838) (paragraph 166), which shows that he was a staunch materialist even as a young man.

On the other hand, Darwin puzzled over the question, “How does consciousness commence,” in his Old and Useless Notes about the moral sense & some metaphysical points (1838-1840, page 35). And in his Descent of Man, published in 1871, Darwin expressed pessimism about the prospects of science being able to identify how consciousness emerged within the foreseeable future:

In what manner the mental powers were first developed in the lowest organisms, is as hopeless an enquiry as how life first originated. These are problems for the distant future, if they are ever to be solved by man.

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter 2, page 36.)

At first blush, Darwin’s pessimism regarding the prospects of science belong able to explain how consciousness originated might seem to suggest that he viewed its emergence as a surprising fact. But I would argue that Darwin’s puzzlement about the manner in which consciousness emerged in no way implies that he would have found the fact that it emerged particularly surprising. As the final paragraph of his Origin of Species shows, he was a thoroughgoing materialist, who viewed “the production of the higher animals” as the inevitable outcome of “laws acting around us.”

Moreover, Darwin’s pessimism about solving the historical question of how consciousness emerged did not prevent him from speculating about the “mental powers” of worms a decade later in his 1881 best-seller, The formation of vegetable mould, through the action of worms, with observations on their habits. For Darwin “mental powers” included conscious sensations and feelings, in addition to intelligence. In any case, Darwin was willing to attribute conscious feelings to worms:

Mental Qualities.—There is little to be said on this head. We have seen that worms are timid. It may be doubted whether they suffer as much pain when injured, as they seem to express by their contortions. Judging by their eagerness for certain kinds of food, they must enjoy the pleasure of eating. Their sexual passion is strong enough to overcome for a time their dread of light. They perhaps have a trace of social feeling, for they are not disturbed by crawling over each other’s bodies, and they sometimes lie in contact. According to Hoffmeister they pass the winter either singly or rolled up with others into a ball at the bottom of their burrows.* Although worms are so remarkably deficient in the several sense-organs, this does not necessarily preclude intelligence, as we know from such cases as those of Laura Bridgman; and we have seen that when their attention is engaged, they neglect impressions to which they would otherwise have attended; and attention indicates the presence of a mind of some kind.

(Original edition, 1881, Chapter 1, page 34.)

Evidently Darwin viewed the question of whether worms possess consciousness as scientifically tractable. After reading what Darwin wrote about cause and effect in his remarks on blue and weight in his Old and Useless Notes, it should not be difficult to envisage how a Darwinian research program into the origin of consciousness might proceed. In the conclusion to his book on worms, Darwin went even further, writing that worms “apparently exhibit some degree of intelligence instead of a mere blind instinctive impulse, in their manner of plugging up the mouths of their burrows.”

(Original edition, 1881, Conclusion, page 312.)

Moving further up the “organic scale” (as he called it), Darwin endeavored to persuade his readers that the gradual evolution and refinement of animals’ mental powers over the course of time was a probable occurrence. He began by arguing that consciousness was widely distributed throughout the animal kingdom:

To return to our immediate subject: the lower animals, like man, manifestly feel pleasure and pain, happiness and misery. Happiness is never better exhibited than by young animals, such as puppies, kittens, lambs, &c., when playing together, like our own children. Even insects play together, as has been described by that excellent observer, P. Huber, who saw ants chasing and pretending to bite each other, like so many puppies.

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter II, page 39.)

Next, Darwin contended that innumerable grades of consciousness could be found in Nature, linking the lowest and highest animals:

…I shall make some few remarks on the probable steps and means by which the several mental and moral faculties of man have been gradually evolved. That this at least is possible ought not to be denied, when we daily see their development in every infant; and when we may trace a perfect gradation from the mind of an utter idiot, lower than that of the lowest animal, to the mind of a Newton.

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter III, page 106)

|

An ant carrying an aphid. According to Darwin, the difference in mental abilities between an ant and an aphid is much greater than the intellectual difference between a man and an ape. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Darwin adduced additional support for his case by arguing that the difference in mental faculties between the highest and lowest animals was one of degree rather than kind, and that the differences in the mental powers of the lower animals were far greater than the differences between the lower and higher animals:

Some naturalists, from being deeply impressed with the mental and spiritual powers of man, have divided the whole organic world into three kingdoms, the Human, the Animal, and the Vegetable, thus giving to man a separate kingdom. (1. Isidore Geoffroy St.-Hilaire gives a detailed account of the position assigned to man by various naturalists in their classifications: ‘Hist. Nat. Gen.’ tom. ii. 1859, pp. 170-189.) Spiritual powers cannot be compared or classed by the naturalist: but he may endeavour to shew, as I have done, that the mental faculties of man and the lower animals do not differ in kind, although immensely in degree. A difference in degree, however great, does not justify us in placing man in a distinct kingdom, as will perhaps be best illustrated by comparing the mental powers of two insects, namely, a coccus or scale-insect and an ant, which undoubtedly belong to the same class. The difference is here greater than, though of a somewhat different kind from, that between man and the highest mammal. The female coccus, whilst young, attaches itself by its proboscis to a plant; sucks the sap, but never moves again; is fertilised and lays eggs; and this is its whole history. On the other hand, to describe the habits and mental powers of worker-ants, would require, as Pierre Huber has shewn, a large volume; I may, however, briefly specify a few points. Ants certainly communicate information to each other, and several unite for the same work, or for games of play. They recognise their fellow-ants after months of absence, and feel sympathy for each other. They build great edifices, keep them clean, close the doors in the evening, and post sentries. They make roads as well as tunnels under rivers, and temporary bridges over them, by clinging together. They collect food for the community, and when an object, too large for entrance, is brought to the nest, they enlarge the door, and afterwards build it up again. They store up seeds, of which they prevent the germination, and which, if damp, are brought up to the surface to dry. They keep aphides and other insects as milch-cows. They go out to battle in regular bands, and freely sacrifice their lives for the common weal. They emigrate according to a preconcerted plan. They capture slaves. They move the eggs of their aphides, as well as their own eggs and cocoons, into warm parts of the nest, in order that they may be quickly hatched; and endless similar facts could be given.

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter VI, pp. 186-187.)

There is no evidence from Darwin’s writings that he viewed the evolution of the lower animals, such as worms, as being particularly surprising. Since Darwin was willing to credit worms with consciousness, we may therefore conclude that Darwin did not regard the emergence of consciousness as a surprising or unexpected event. Rather, the evidence suggests that he would have viewed it as the natural outcome of biological laws of variation, acting on simple organisms.

(c) Why Darwin regarded the appearance of human intelligence as an unsurprising fact

|

Rodin’s Thinker (1902). Musee Rodin, Paris. Image courtesy of Daniel Stockman and Wikipedia.

Darwin was even more sanguine about the prospects for explaining the appearance of human intelligence. In his 1871 work, The Descent of Man, Darwin argued that the emergence of human intelligence was an unsurprising fact, in view of the continuity (as he perceived it) between our mental abilities and those of the “higher animals,” and the survival advantage conferred by intelligence. Darwin maintained that “the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, is certainly one of degree and not of kind”

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter III, p. 105), and he charted the steps leading to man in a well-known passage:

In the class of mammals the steps are not difficult to conceive which led from the ancient Monotremata to the ancient Marsupials; and from these to the early progenitors of the placental mammals. We may thus ascend to the Lemuridae and the interval is not wide from these to the Simiadae. The Simiadae then branched off into two great stems, the New World and Old World monkeys; and from the latter, at a remote period, Man, the wonder and glory of the Universe, proceeded.”

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter VI, p. 213.)

Darwin maintained that because human intelligence conferred a survival advantage on its possessors, the gradual improvement of intelligence in our ape-like ancestors could easily be explained by his theory of evolution by natural selection. Indeed, Darwin advanced this argument in order to rebut the view, put forward by Wallace in an essay in the Quarterly Review of April 1869, that the special intervention of a Higher Intelligence was necessary in order to account for the evolution of human beings from ape-like ancestors:

The case, however, is widely different, as Mr. Wallace has with justice insisted, in relation to the intellectual and moral faculties of man. These faculties are variable; and we have every reason to believe that the variations tend to be inherited. Therefore, if they were formerly of high importance to primeval man and to his ape-like progenitors, they would have been perfected or advanced through natural selection. Of the high importance of the intellectual faculties there can be no doubt, for man mainly owes to them his predominant position in the world. We can see, that in the rudest state of society, the individuals who were the most sagacious, who invented and used the best weapons or traps, and who were best able to defend themselves, would rear the greatest number of offspring. The tribes, which included the largest number of men thus endowed, would increase in number and supplant other tribes.

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter V, p. 159.)

Darwin acknowledged that there were certain mental capacities that were unique to human beings, but he minimized the force of this fact by arguing that these abilities originated as by-products of other mental abilities that man shared with the beasts:

We have seen that the senses and intuitions, the various emotions and faculties, such as love, memory, attention, curiosity, imitation, reason, &c., of which man boasts, may be found in an incipient, or even sometimes in a well-developed condition, in the lower animals. They are also capable of some inherited improvement, as we see in the domestic dog compared with the wolf or jackal. If it be maintained that certain powers, such as self-consciousness, abstraction, &c., are peculiar to man, it may well be that these are the incidental results of other highly-advanced intellectual faculties; and these again are mainly the result of the continued use of a highly developed language. At what age does the new-born infant possess the power of abstraction, or become self-conscious and reflect on its own existence? We cannot answer; nor can we answer in regard to the ascending organic scale.

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter III, pp. 105-106)

The human capacity for language, however, was not a by-product: for Darwin, it arose by a gradual evolutionary process of progressive modification and refinement of capacities that were already widespread amongst mammals:

“With respect to the origin of articulate language, after having read on the one side the highly interesting works of Mr. Hensleigh Wedgwood, the Rev. F. Farrar, and Prof. Schleicher, and the celebrated lectures of Prof. Max Muller on the other side, I cannot doubt that language owes its origin to the imitation and modification, aided by signs and gestures, of various natural sounds, the voices of other animals, and man’s own instinctive cries.”

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter II, p. 56)“The half-art and half-instinct of language still bears the stamp of its gradual evolution.“

(The Descent of Man, 1st edition, 1871, Chapter III, p. 106.)

To sum up: Darwin believed that the origin of life was a scientifically tractable problem which would eventually be explained in terms of the laws of chemistry; that the phenomenon of consciousness could be explained causally in terms of physical sensations and memories, and that his new theory of evolution by natural selection could account for the emergence of human intelligence in a very straightforward manner.

(d) The explanatory merits of Darwinism vs. fairy magic

So I was quite astonished when I read philosopher Elliott Sober chiding Professor Thomas Nagel in his review, for holding views which Darwin himself held: namely, that a successful theory of origins must be able to demonstrate that the origin of life and intelligence were unsurprising events, with a reasonable chance of occurring, over the course of time:

Nagel thinks that adequate explanations of the origins of life, intelligence, and consciousness must show that those events had a “significant likelihood” of occurring: these origins must be shown to be “unsurprising if not inevitable.” A complete account of consciousness must show that consciousness was “something to be expected.” Nagel thinks that evolutionary theory as we now have it fails in this regard, so it needs to be supplemented…

My philosophical feelings diverge from Nagel’s… I don’t think that life, intelligence, and consciousness had to be in the cards from the universe’s beginning. I am happy to leave this question to the scientists. If they tell me that these events were improbable, I do not shake my head and insist that the scientists must be missing something. There is no such must. Something can be both remarkable and improbable.

What Darwin realized, and what Sober appears not to recognize, is that the intellectual appeal of evolution over creationism rests on its being able to account for the history of life on Earth without resorting to ad hoc explanations. Necessarily, any account of the history of life on our planet has to include its beginning, and also the appearance of sentient and sapient life-forms. At the very least, a viable naturalistic theory of origins must demonstrate its ability to account for these events by producing a causally adequate mechanism for the job at hand. But since no physical process has ever been observed to generate life, consciousness or intelligence, the only way to establish the adequacy of a naturalistic theory of origins is to provide a logical argument showing that given enough time, these events were not at all improbable, and that there was some measurable likelihood of their occurrence. Without such an argument, what is the scientific advantage of explaining life in terms of Darwinian evolution, rather than (say) magic?

More than two years ago, I wrote a post on Uncommon Descent, entitled, The 10^(-120) challenge, or: The fairies at the bottom of the garden, in which I challenged neo-Darwinists to provide me with an empirical or mathematical demonstration that the probability of the emergence of life on Earth during the past four billion years as a result of unguided natural processes, starting from a random assortment of organic chemicals, is greater than 10^(-120), or 1 in 1 trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion. As you can see, I set the bar very, very low. No-one from the Darwinist camp took me up on the challenge. I concluded my post on a mocking note, observing that the claim that unguided natural processes (e.g. random mutation and natural selection) produced the first life on Earth is even less scientifically supportable than the fanciful assertion that fairies did the job.

4. Do Nagel’s critics succeed in their attempt to render the origin of life unsurprising?

|

A game of Scrabble. Many origin-of-life researchers believe that RNA gave rise to both DNA and proteins, but they fail to realize that the appearance of RNA in the first place is astronomically improbable. Professor Dr. Robert Shapiro (1935-2011), who was professor emeritus of chemistry at New York University, has declared: “[S]uppose you took Scrabble sets, or any word game sets, blocks with letters, containing every language on Earth, and you heap them together and you then took a scoop and you scooped into that heap, and you flung it out on the lawn there, and the letters fell into a line which contained the words ‘To be or not to be, that is the question,’ that is roughly the odds of an RNA molecule … appearing on the Earth.” Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

(a) Why the RNA world and the metabolism-first scenario are both fatally flawed explanations for the origin of life

In his review, Professor Elliott Sober argues that even if the evolution of life on Earth should prove to be highly improbable, its appearance at some time and some place in the universe could well be a highly probable occurrence. On this theoretical point, Sober is of course correct; however, he appears to be unaware of recent work by Dr. Douglas Axe, showing that the appearance of even one functional protein, of any kind, was an event so improbable that we would not expect it to happen anywhere in the observable universe, during its 13.7-billion-year history. Dr. Axe has calculated the odds of getting even one functional protein of modest length (150 amino acids) of any kind, by chance, from a pre-biotic soup as less than 1 in 10^164. And in a recent article, The Case Against a Darwinian Origin of Protein Folds (BioComplexity 2010(1):1-12. doi:10.5048/BIO-C.2010.1), Dr. Axe came up with even more daunting odds relating to the likelihood of a new metabolic pathway evolving by chance:

Based on analysis of the genomes of 447 bacterial species, the projected number of different domain structures per species averages 991. Comparing this to the number of pathways by which metabolic processes are carried out, which is around 263 for E. coli, provides a rough figure of three or four new domain folds being needed, on average, for every new metabolic pathway. In order to accomplish this successfully, an evolutionary search would need to be capable of locating sequences that amount to anything from one in 10^159 to one in 10^308 possibilities, something the neo-Darwinian model falls short of by a very wide margin. (p. 11)

The total number of events (or “elementary logical operations”) that could have occurred in the observable universe since the Big Bang has been calculated as no more than 10 to the power of 120 by MIT researcher Seth Lloyd, in his 2002 article, Computational capacity of the universe (Physics Review Leters 88 (2002) 237901, DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.237901). So on the best available evidence, the appearance of a protein anywhere in the universe would still be a fantastically improbable event, unless we can point to a non-stochastic process which is more likely to generate proteins than chance alone, or an environment on some other planet that would have been more likely to generate proteins than the primordial Earth. In his ground-breaking book, Signature in the Cell, Dr. Stephen Meyer reviewed non-stochastic processes in detail and concluded that they were unable to account for the specified information we find in proteins, as opposed to the repetitive order we see in polymers.

Indeed, the odds against proteins forming by unguided natural processes are so formidable that many scientists – including biologist H. Allen Orr, who also reviewed Nagel’s book, Mind and Cosmos – now believe that another molecule – RNA – formed first, and that proteins were formed from RNA. In his review, Professor Orr hawks the “RNA world” very persuasively to his readers:

The origin of life is admittedly a hard problem and we don’t know exactly how the first self-replicating system arose. But big progress has been made. The discovery of so-called ribozymes in the 1980s plausibly cracked the main principled problem at the heart of the origin of life. Research on life’s origin had always faced a chicken and egg dilemma: DNA, our hereditary material, can’t replicate without the assistance of proteins, but one can’t get the required proteins unless they’re encoded by DNA. So how could the whole system get off the ground?

Answer: the first genetic material was probably RNA, not DNA. This might sound like a distinction without a difference but it isn’t. The point is that RNA molecules can both act as a hereditary material (as DNA does) and catalyze certain chemical reactions (as some proteins do), possibly including their own replication. (An RNA molecule that can catalyze a reaction is called a ribozyme.) Consequently, many researchers into the origins of life now believe in an “RNA world,” in which early life on earth was RNA-based. “Physical accidents” were likely still required to produce the first RNA molecules, but we can now begin to see how these molecules might then self-replicate.

Orr is a highly qualified biologist, so he must be aware of what Dr. Robert Shapiro (1935-2011), Professor Emeritus of Chemistry at New York University, had to say about the plausibility of the “RNA world” hypothesis. Shapiro realized that the same problem arises for RNA as for proteins: the vast majority of possible sequences are non-functional, and only an astronomically tiny proportion work. In a discussion hosted by Edge magazine in 2008, entitled, Life! What a Concept, with scientists Freeman Dyson, Craig Venter, George Church, Dimitar Sasselov and Seth Lloyd, Shapiro explained why he found the RNA world hypothesis utterly incredible:

…[S]uppose you took Scrabble sets, or any word game sets, blocks with letters, containing every language on Earth, and you heap them together and you then took a scoop and you scooped into that heap, and you flung it out on the lawn there, and the letters fell into a line which contained the words “To be or not to be, that is the question,” that is roughly the odds of an RNA molecule, given no feedback – and there would be no feedback, because it wouldn’t be functional until it attained a certain length and could copy itself – appearing on the Earth.

As is well-known, Professor Shapiro himself favored a “metabolism-first” scenario for the origin of life. However, a recent article entitled, Lack of evolvability in self-sustaining autocatalytic networks: A constraint on the metabolism-first path to the origin of life by Vera Vasasa, Eors Szathmary and Mauro Santos (PNAS January 4, 2010, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912628107) has highlighted a fundamental problem with the “metabolism-first” scenario: proto-metabolic systems would have been incapable of undergoing Darwinian evolution. In their Abstract, the authors point out that replication of compositional information in the metabolism-first scenario “is so inaccurate that fitter compositional genomes cannot be maintained by selection and, therefore, the system lacks evolvability.” The paper concludes:

We think that the real question is that of the organization of chemical networks. If (and what a big IF) there can be in the same environment distinct, organizationally different, alternative autocatalytic cycles/networks, as imagined for example by Ganti (37) and Wachtershauser (38, 39), then these can also compete with each other and undergo some Darwinian evolution. But, even if such systems exist(-ed), they would in all probability have limited heredity only (cf ref. 34) and thus could not undergo open-ended evolution.

(b) Sober’s “200 probable steps” leading to the appearance of conscious life

At this point, it looks as if Darwin’s modern defenders are down for the count. The origin of life appears to be something of a miracle, and there is no prospect of our being able to explain the emergence of consciousness in terms that we can understand. But Elliott Sober mounts a strong comeback, by proposing an interesting thought experiment in his review of Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos. Briefly, he contends that for all we know, each of the physical steps leading to the first life, and eventually to the appearance of conscious life, may well have been highly probable. In that case, if the emergence of life and consciousness occurred by such a process – and we cannot show that it did not – then it would surely be unreasonable to ask for anything further, by way of an explanation. Even if the eventual outcome (the appearance of conscious life-forms) turns out to be antecedently very unlikely due to the vast number of steps that had to be traversed, the fact that each individual step was highly probable should be enough for us, and no more need be said:

Before leaving the topic of probability, I want to highlight what is involved in Nagel’s requirement that the facts he says are remarkable must be shown to be unsurprising. For the sake of concreteness, let’s take this to mean that the probability must be greater than 1/2. Suppose that to get from the universe’s first moment to the origin of consciousness, 200 stages must be traversed. The universe starts at stage S1, then it needs to pass to S2, then to S3, and so on, until it reaches S200, at which time consciousness makes its first appearance. Suppose further that we have a theory that says that the probability of going from each of these stages to the next is 99/100: this means that each individual step is very likely. Still, the probability of going from S1 all the way to S200 is (99/100)^199, or about 1/10. The demand that the origin of consciousness must have had a probability greater than 1/2 entails that the theory I just described must be wrong or seriously incomplete.

(c) What’s wrong with Sober’s 200 steps: the parable of the tightrope-walker

|

Photo of Maria Spelterini, walking across a tightrope across the Niagara Gorge, from the United States side to Canada, on 8 July, 1876. Image courtesy of Niagara Falls Public Library and Wikipedia.

I have to say that I find Sober’s reasoning faulty here. To see why, let us imagine a tightrope walker named Letitia, who performs in a circus. Her standard walk is 10 meters long, and her track record indicates that whenever she attempts to walk 10 meters on a tightrope, there is a 99% chance that she will succeed – which is why Letitia never performs her tightrope walk without a safety net. As she is young and has lots of stamina, Letitia’s concentration does not flag over longer distances: thus, over a distance which is N times longer than her standard 10-meter walk, the chance that she will succeed is 0.99^N. We would not consider it too astonishing if Letitia walked along a 100-meter tightrope without falling over; but if she managed to traverse a 2-kilometer tightrope (which is 200 of her standard walks) without falling over, I think most of us would regard that as a somewhat remarkable feat. Still, we might say that she was just lucky; after all, as Sober might point out, the probability that she would succeed was about 1/10 (actually, it’s just under 13.4%). But now let us suppose that the very next day, Letitia manages to complete a 20-kilometer tightrope walk. The odds of this happening by chance are much lower: 0.99^2000, or about 1 in 500 million. At this point, I think most of us would demand an explanation, and we might reasonably suspect that she was cheating: perhaps she was using a fine, invisible wire to help support her. However, when asked about this, Letitia vehemently denies the allegation of cheating, arguing as follows: “There’s nothing surprising about what I did. Sure, I traversed a distance that was equal to 2000 of my standard walks, but the chance that I would complete each stage was 99 in 100. So what’s the big deal?”

We would not be at all impressed by such an argument; and neither should we be by Sober’s example of a 200-stage process leading to the appearance of consciousness. If the origin of life and/or consciousness turns out to be a fantastically improbable event that would not normally be expected to happen even once in the entire history of the universe (as I have argued above), then the fact that each step along the path leading to life and/or consciousness had a 99% chance of being traversed should not lessen our wonderment one little bit. The traversal of the entire path is what needs to be explained, and if the number of steps is large enough, that event will turn out to be astronomically unlikely.

But let us suppose that Letitia continues her protestations of innocence. She pulls out a deck of cards, and deals out several poker hands. “Look,” she says. “Highly improbable events happen all the time. Your poker hand is highly improbable: it’s very unlikely that those particular cards would be dealt. Yet you don’t demand an explanation of that fact. So why do you insist that there must be some explanation of my tightrope-walking feat today? The fact is, there is no explanation. I just got lucky, that’s all. I can’t explain it any more than you can.”

Sober, in his review of Nagel’s book, makes a similar argument, when he points out that some people win the lottery twice, but I would argue that it is a faulty illustration. Double lottery wins do occur; but they are a lot less frequent than single wins, as the laws of probability predict. The same goes for lucky hands. Poker hands obey the laws of probability: very unlikely hands (such as a royal flush) do appear on rare occasions, but more probable hands, such as three of a kind, are much more common. What makes us suspicious of Letitia’s feat is that it is so atypical: an isolated success, very early in her career, with nothing remotely comparable to match it. If she had successfully walked 18, 16 or even 10 kilometers on several previous occasions, we might credit her feat; but if her previous best was 2 kilometers, then we have every right to be skeptical. In short: it is entirely legitimate to look for an alternative explanation of a highly atypical and inherently improbable feat, which renders it more probable than it otherwise would be. And if the feat in question is so improbable that would not normally be expected to happen even once in the history of the universe, then it would be intellectually perverse not to look for an alternative explanation for its occurrence, which rendered it more likely to occur.

The appearance of life can legitimately be described as a feat like Letitia’s tightrope walk, because organisms can do lots of very impressive things: a living cell is an amazing nanoscale factory, whose workings we are still struggling to comprehend. Even a humble protein performs a useful function within a cell; thus the generation of such a protein can also be described as quite a feat. Given the staggering odds against the formation of proteins, let alone living cells or conscious beings, by known natural processes, the quest for an alternative, more probable explanation becomes a scientific imperative.

5. Is a teleological theory of Nature compatible with the scientific method?

|

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) proposed a teleological account of science which remained popular in Europe for almost 2,000 years after his death. This bust is a copy of a lost 1st or 2nd century bronze sculpture, made by Lysippos. Image courtesy of the Musee du Louvre, Eric Gaba and Wikipedia.

It is a curious fact that of the three critical reviews I read of Professor Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Cosmos, the one which was most open to the possibility of a genuinely teleological theory of Nature was written by a biologist, while the most decisive rejection of this possibility was penned by a philosopher.

(a) What exactly is Nagel proposing in his teleological theory of Nature?

It needs to be borne in mind that Nagel is an atheist, and that the teleological theory of Nature which he puts forward is an entirely naturalistic one, as Professor H. Allen Orr explains in his review:

While we often associate teleology with a God-like mind – events occur because an agent wills them as means to an end – Nagel finds theism unattractive. But he insists that materialism and theism do not exhaust the possibilities.

Instead he proposes a special species of teleology that he calls natural teleology. Natural teleology doesn’t depend on any agent’s intentions; it’s just the way the world is. There are teleological laws of nature that we don’t yet know about and they bias the unfolding of the universe in certain desirable directions, including the formation of complex organisms and consciousness. The existence of teleological laws means that certain physical outcomes “have a significantly higher probability than is entailed by the laws of physics alone – simply because they are on the path toward a certain outcome.”

Nagel intends natural teleology to be, among other things, a biological theory. It would explain not only the “appearance of physical organisms” but the “development of consciousness and ultimately of reason in those organisms.” Teleology would also provide an “account of the existence of the biological possibilities on which natural selection can operate.”…

One would think, then, that scientists of an atheistic bent, with a philosophical commitment to naturalism, should not find Nagel’s proposals too unsettling. All Nagel is really saying is that it’s a brute fact about Nature that it is biased towards the generation of life and consciousness. Nothing more than that. And yet the ferocity of the Darwinist resistance to even this modest proposal is quite surprising.

(b) Orr’s admission: for all we know, Nature might be teleological

Professor Orr is a biologist whose scientific training is steeped in Darwinism. Despite this fact, I am happy to report that Orr has no objection in principle to Nagel’s teleological views. As he puts it in his review:

I will also be the first to admit that we cannot rule out the formal possibility of teleology in nature. It could turn out that teleological laws affect how the universe unfolds through time. While I suspect some might regard such heterodoxy as a crime against science, Nagel is right that there’s nothing intrinsically unscientific about teleology. If that’s the way nature is, that’s the way it is, and we scientists would need to get on with the business of characterizing these surprising laws. Teleological science is, in fact, more than imaginable. It’s actual, at least historically. Aristotelian science, with its concern for final cause, was thoroughly teleological. And the biological tradition that Darwinism displaced, natural theology, also featured a good deal of teleological thinking.

I believe in giving credit where credit is due, so I would like to thank Orr for opening the door, if ever so slightly, to teleology in the scientific world, even if (as we shall see below), he personally has little time for the notion.

(c) Sober’s rejection of Nagel’s teleological theory of Nature: there can be no teleology without efficient causality

Philosopher Elliott Sober will have none of it, however. His principal objection to Nagel’s proposed scientific program is that in order for teleological facts to be scientific, they have to be explicable not in terms of future states of affairs, but past ones – namely, their causal antecedents. As he puts it in his review:

I do not reject teleology wholesale. I do not reject claims such as “flowers have bright petals because they attract pollinators” and “Sally went to the park at 8:30 because there were fireworks at 9 o’clock.” These statements do not say that a later event caused an earlier one, but they are true because certain causal facts are in place. The statement about flowers is true because there was selection for bright colors among plants that gained from the services of pollinators that used color vision. The statement about fireworks is true because Sally knew there would be fireworks at 9 o’clock, and she wanted to arrive in time to get a good seat. Maybe there are true teleological statements about life, mind, or consciousness. But if there are causal underpinnings for those teleological statements, as there are for the teleological statements about flowers and fireworks, the materialist need not object.

Nagel’s thesis is not just that there are true teleological statements about the emergence of life, mind, and consciousness, but that these statements cannot be explained by a purely causal/materialistic science. Only then does his teleology go beyond what materialistic reductionism allows.

Here, Sober has astutely identified the Achilles’ heel of a naturalistic account of forward-looking teleology: Nature, being unintelligent, does not and cannot look forward. It is precisely for this reason that the Intelligent Design movement contends that the emergence of life and consciousness can only be adequately explained in terms of a Mind which produced them. Nagel, who dislikes theism, does not want to go down this path.

Now, it is one thing to critique the philosophical assumptions underlying Nagel’s teleological account of Nature. It is quite another thing, however, to dogmatically rule out scientific investigation of the claim that some biological changes occurring in Nature are forward-looking, simply because these events “cannot be explained by a purely causal/materialistic science.” If such events occur, then they can and should be scientifically investigated. In that case, it is best that we investigate them as speedily as possible, and move on from there.

6. Are there any good scientific arguments against Nagel’s teleological theory of Nature?

|

Restoration of Tyrannosaurus rex in a walking posture. Professor H. Allen Orr invokes the extinction of T. rex as a scientific argument against Thomas Nagel’s teleological version of evolution, which says that the universe contains a built-in bias towards the production of sentient and sapient life-forms. Image courtesy of myfavoritedinosaur.com, LadyofHats and Wikipedia.

(a) Why so many non-sentient organisms?

Reading through the reviews of Nagel’s book, I was struck by the weakness of the scientific arguments mounted against Nagel’s teleological theory of Nature. Pulling it apart should have been an easy task for a Darwinist. When I read biologist H. Allen Orr’s review, I expected to encounter substantive criticisms. Instead, what I got was this:

Here’s another problem. Nagel’s teleological biology is heavily human-centric or at least animal-centric. Organisms, it seems, are in the business of secreting sentience, reason, and values. Real biology looks little like this and, from the outset, must face the staggering facts of organismal diversity. There are millions of species of fungi and bacteria and nearly 300,000 species of flowering plants. None of these groups is sentient and each is spectacularly successful. Indeed mindless species outnumber we sentient ones by any sensible measure (biomass, number of individuals, or number of species; there are only about 5,500 species of mammals). More fundamentally, each of these species is every bit as much the end product of evolution as we are. The point is that, if nature has goals, it certainly seems to have many and consciousness would appear to be fairly far down on the list…