Transcription is certainly the essential node in the complex network of procedures and regulations that control the many activities of living cells. Understanding how it works is a fascinating adventure in the world of design and engineering. The issue is huge and complex, but I will try to give here a simple (but probably not too brief) outline of its main features, always from a design perspective.

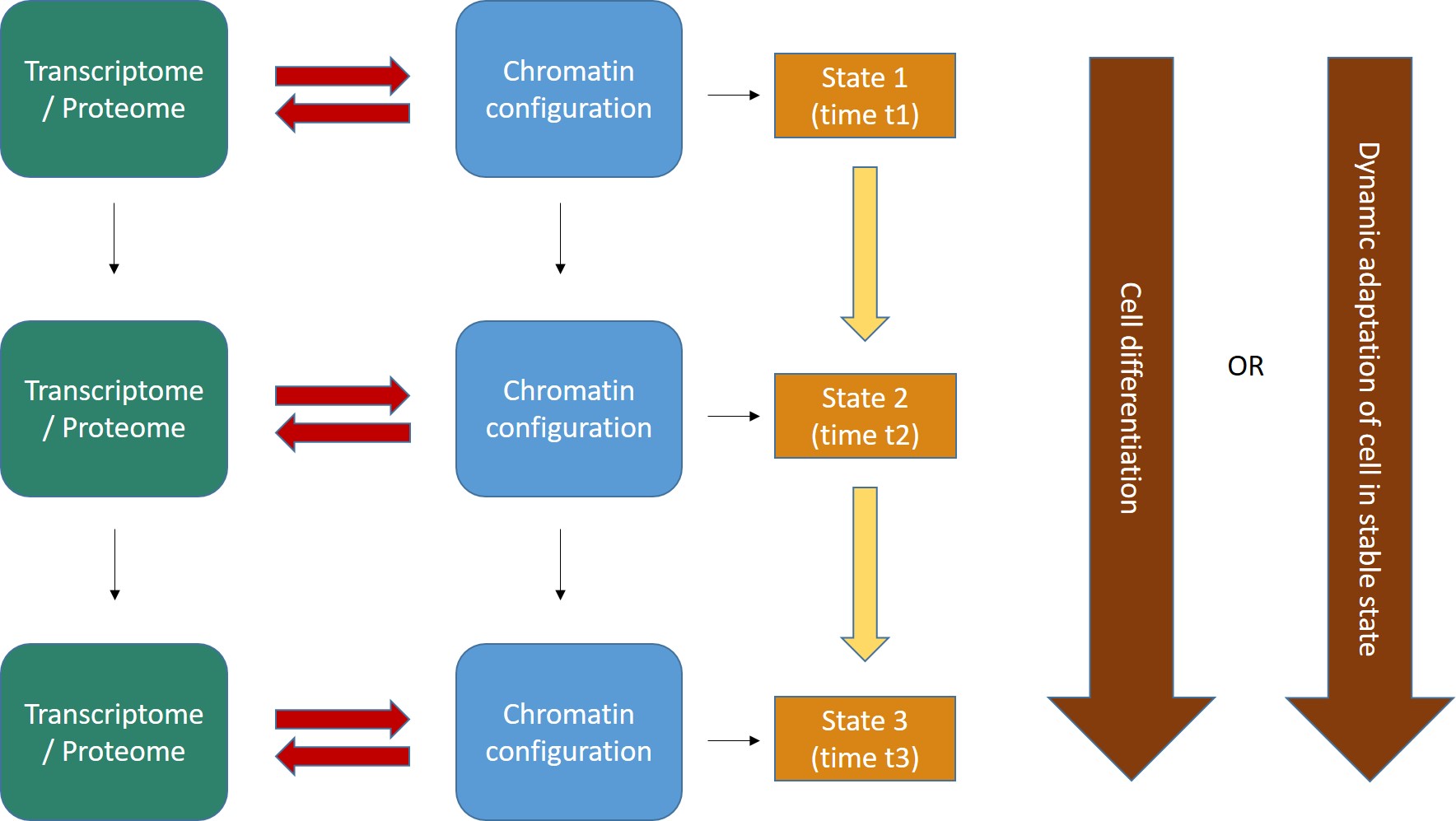

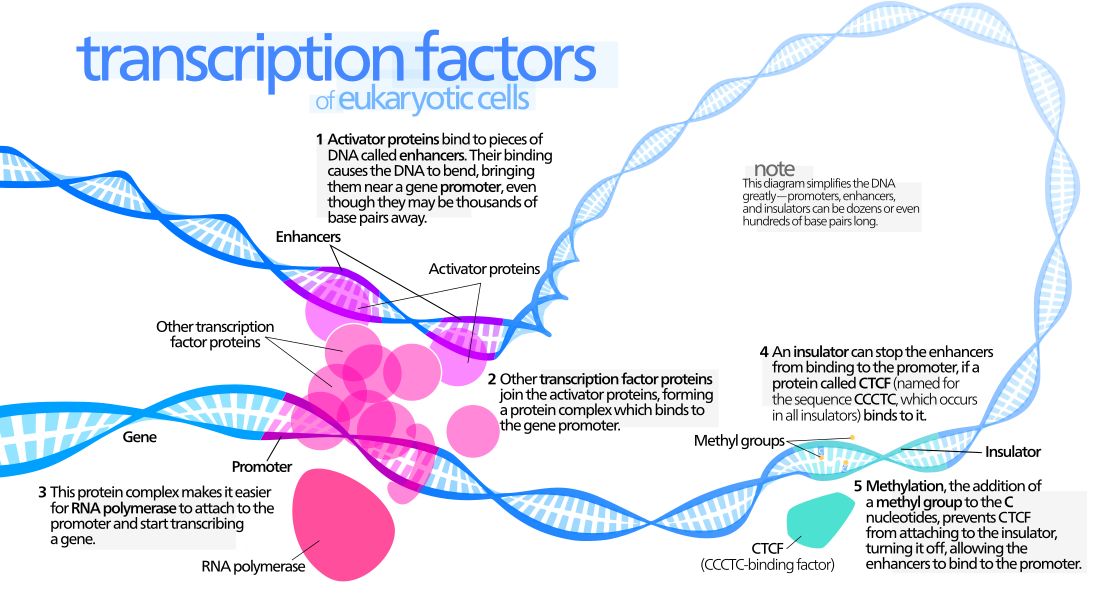

Fig. 1 A simple and effective summary of a gene regulatory network

Introduction: where is the information?

One of the greatest mysteries in cell life is how the information stored in the cell itself can dynamically control the many changes that continuosly take place in living cells and in living beings. So, the first question is: what is this information, and where is it stored?

Of course, the classical answer is that it is in DNA, and in particular in protein coding genes. But we know that today that answer is not enough.

Indeed, a cell is an ever changing reality. If we take a cell, any cell, at some specific time t, that cell is the repository of a lot of information, at that moment and in that state. That information can be grossly divided in (at least) two different compartments:

a) Genomic information, which is stored in the sequence of nucleotides in the genome. This information is relatively stable and, with a few important exceptions, is the same in all the cells of a multicellular being.

b) Non genomic information. This includes all the specific configurations which are present in that cell at time t, and in particular all epigenetic information (configurations that modify the state of the genomic information) and, more generally, all configurations in the cell. The main components of this dynamic information are the cell transcriptome and proteome at time t and the sum total of its chromatin configurations.

Now, let’s try to imagine the flow of dynamic information in the cell as a continuous interaction between these two big levels of organization:

- The transcriptome/proteome is the sum total of all proteins and RNAs (and maybe other functional molecules) that are present in the cell at time t, and which define what the cell is and does at that time.

- The chromatin configuration can be considered as a special “reading” of the genomic information, individualized by many levels of epigenetic control. IOWs, while the genomic information is more or less the same in all cells, it can be expressed in myriads of different ways, according to the chromatin organization at that moment, which determines what genes or parts of the genome are “available” at time t in the cell. In this way, one genomic sequence can be read in multiple different ways, with different functional meanings and effects. So, if we just stick to protein coding genes, the 20000 genes in the human genome are available only partially in each cell at each moment, and that allows for a myriad of combinatorial dynamic “readings” of the one stable genome.

Fig. 2 shows the general form of these concepts.

Fig. 2

Two important points:

- The interaction between transcriptome/proteome and chromatin configuration is, indeed, an interaction. The transcriptome/proteome determines the chromatin configuration in many ways: for example, changing the methylation of DNA (DNA methyltransferases); or modifying the post-trascriptional modifications (methylation, acetylation, ubiquitination and others) of histones (covalent histone-modifying complexes), or creating new loops in chromatin (transcription factors); or directly remodeling chromatin itself (ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes). In the same way, any modification of the chromatin landscape immediately influences what the existing transcriptome/proteome is and can do, because it directly changes the transcriptome/proteome as a result of the changes in gene transcription. Of course, this can modify the availability of genes, promoters, enhancers, and regulatory regions in general at chromatin level. That’s the meaning of the two big red arrows connecting, at each stage, the two levels of regulation. The same concept is evident in Fig. 1, which shows how the output of transcription has immediate, complex and constant feedback on transcription regulation itself.

- As a result of the continuous changes in the trascriptome/proteome and in chromatin configurations, cell states continuously change in time (yellow arrows). However, this continuous flow of different functional states in each cell can have two different meanings, as shown by the two alternative big brown arrows on the right:

- Cells can change dramatically, following a definite developmental pathaway: that’s what happens in cell differentiation, for example from a haematopoietic stem cell to differentiated blood cells like lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and so on. The end of the differetiation is the final differentiated cell, which is in a sense more “stable”, having reached its final intended “form”.

- Those “stable” differentiated cells, however, are still in a continuous flow of informational change, which is still drawn by continuous modifications in the transcriptome/proteome and in chromatin configurations. Even if these changes are less dramatic, and do not change the basic identity of the differentiated cell, still they are necessary to allow adaptation to different contexts, for example varying messages from near cells or from the rest of the body, either hormonal, or neurologic, or other, or other stimuli from the environment (for example, metabolic conditions, stress, and so on), or even simply the adherence to circadian (or other) rythms. IOWs, “stable” cells are not stable at all: they change continuously, while retaining their basic cell identity, and those changes are, again, drawn by continuous modifications in the transcriptome/proteome and in the chromatin configurations of the cell.

Now, let’s have a look at the main components that make the whole process possible. I will mention only briefly the things that have been known for a long time, and will give more attention to the components for which there is some recent deeper understanding available.

We start with those components that are part of the DNA sequence itself, IOWs the genes themselves and those regions of DNA which are involved in their trancription regulation (cis-regulatory elements).

Cis elements

Genes and promoters.

Of course, genes are the oldest characters in this play. We have the 20000 protein coding genes in human genome, which represent about 1.5% of the whole genomic sequence of 3 billion base pairs. But we must certainly add the genes that code for non coding RNAs: at present, about 15000 genes for long non coding RNAs, and about 5000 genes for small non coding RNAs, and about 15000 pseudogenes. So, the concept of gene is now very different than in the past, and it includes many DNA sequences that have nothing to do with protein coding. Moreover, it is interesting to observe that many non protein coding genes, in particular those that code for lncRNAs, have a complex exon-intron structure, like protein coding genes, and undego splicing, and even alternative splicing. For a good recent review about lncRNAs, see here:

Let’s go to promoters. This is the simple definition (from Wikipedia):

In genetics, a promoter is a region of DNA that initiates transcription of a particular gene. Promoters are located near the transcription start sites of genes, on the same strand and upstream on the DNA (towards the 5′ region of the sense strand). Promoters can be about 100–1000 base pairs long.

A promoter includes:

- The transcription start site (TSS), IOWs the point where transcription starts

- A binding site for RNA polymerase

- General transcription factors binding sites for , such as the TATA box and the BRE in eukaryotes

- Other parts that can interact with different regulatory elements.

Promoters have been classified as ‘focused’ or ‘sharp’ promoters (those that have a single, well-defined TSS), and ‘dispersed’ or ‘broad’ promoters (those that have multiple closely spaced TSS that are used with similar frequency).

For a recent review of promoters and their features, see here:

Eukaryotic core promoters and the functional basis of transcription initiation

Enhancers

Enhancers are a fascinating, and still poorly understood, issue. Again, here is the definition from Wikipedia:

In genetics, an enhancer is a short (50–1500 bp) region of DNA that can be bound by proteins (activators) to increase the likelihood that transcription of a particular gene will occur. These proteins are usually referred to as transcription factors. Enhancers are cis-acting. They can be located up to 1 Mbp (1,000,000 bp) away from the gene, upstream or downstream from the start site. There are hundreds of thousands of enhancers in the human genome. They are found in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Enhancers are elusive things. The following paper:

Transcribed enhancers lead waves of coordinated transcription in transitioning mammalian cells

reports a total of 201,802 identified promoters and 65,423 identified enhancers in humans, and similar numbers in mouse (this in 2015). But there are probably many more than that number.

Working with specific TFs, enhancers are the main responsibles of the formation of dynamic chromatin loops, as we will see later.

Here is a recent paper about human enhancers in different tissues:

Genome-wide Identification and Characterization of Enhancers Across 10 Human Tissues.

Abstract:

Background: Enhancers can act as cis-regulatory elements (CREs) to control development and cellular function by regulating gene expression in a tissue-specific and ubiquitous manner. However, the regulatory network and characteristic of different types of enhancers(e.g., transcribed/non-transcribed enhancers, tissue-specific/ubiquitous enhancers) across multiple tissues are still unclear. Results: Here, a total of 53,924 active enhancers and 10,307 enhancer-associated RNAs (eRNAs) in 10 tissues (adrenal, brain, breast, heart, liver, lung, ovary, placenta, skeletal muscle and kidney) were identified through the integration of histone modifications (H3K4me1, H3K27ac and H3K4me3) and DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs) data. Moreover, 40,101 tissue-specific enhancers (TS-Enh), 1,241 ubiquitously expressed enhancers (UE-Enh) as well as transcribed enhancers (T-Enh), including 7,727 unidirectionally transcribed enhancers (1D-Enh) and 1,215 bidirectionally transcribed enhancers (2D-Enh) were defined in 10 tissues. The results show that enhancers exhibited high GC content, genomic variants and transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) enrichment in all tissues. These characteristics were significantly different between TS-Enh and UE-Enh, T-Enh and NT-Enh, 2D-Enh and 1D-Enh. Furt hermore, the results showed that enhancers obviously upregulate the expression of adjacent target genes which were remarkably correlated with the functions of corresponding tissues. Finally, a free user-friendly tissue-specific enhancer database, TiED (http://lcbb.swjtu.edu.cn/TiED), has been built to store, visualize, and confer these results. Conclusion: Genome-wide analysis of the regulatory network and characteristic of various types of enhancers showed that enhancers associated with TFs, eRNAs and target genes appeared in tissue specificity and function across different tissues.

Promoter and enhancer associated RNAs

A very interesting point which has been recently clarified is that both promoters and enhancers, when active, are transcribed. IOWs, beyond their classical action as cis regulatory elements (DNA sequences that bind trans factors), they also generate specific non coding RNAs. They are called respectively Promoter-associated RNAs (PARs) and Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs). They can be short or long, and both types seem to be functional in transcription regulation.

Here is a recent paper that reciews what is known of PARs, and their “cousins” terminus-associated RNAs (TARs):

Classification of Transcription Boundary-Associated RNAs (TBARs) in Animals and Plants

Here, instead, is a recent review about eRNAS:

Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs): New Insights into Gene Transcription and Disease Treatment

Abstract:

Enhancers are cis-acting elements that have the ability to increase the expression of target genes. Recent studies have shown that enhancers can act as transcriptional units for the production of enhancer RNAs (eRNAs), which are hallmarks of activity enhancers and are involved in the regulation of gene transcription. The in-depth study of eRNAs is of great significance for us to better understand enhancer function and transcriptional regulation in various diseases. Therefore, eRNAs may be a potential therapeutic target for diseases. Here, we review the current knowledge of the characteristics of eRNAs, the molecular mechanisms of eRNAs action, as well as diseases related to dysregulation of eRNAs.

So, this is a brief description of the essential cis regulatory elements. Let’s go now to trans regulatory elements, IOWs those molecules that are not part of the DNA sequence, but work on it to regulate gene transcription.

Trans elements

The first group of trans acting tools includes those molecules that are the same for all transcriptions. They are “general” transcription tools.

I will start with a brief mention of RNA polymerase, which is not a regulatory element, but rather the true effector of transcription:

DNA-directed RNA polymerases

This is a family of enzymes found in all living organisms. They open the double-stranded DNA and implement the transciption, synthesizing RNA from the DNA template.

I don’t want to deal in detail with this complex subject: suffice it to say, for the moment, that RNA polymerases are very big and very complex proteins, with some basic information shared fron prokaryotes to multicellular organisms. In humans, RNA polymerase II is the one responsible of the transcription of protein coding mRMAs, and of some non coding RNAs, including many lncRNAs. Just as an example, human RNA Pol II is a multiprotein complex of 12 subunits, for a sum total of more than 4500 AAs.

Now, let’s go to the general regulatory elements:

General TFs

Grneral TFs are transcription factors that bind to promoter to allow the start of transcription. They are called “general” because they are common to all transcriptions, while specific TFs act on specific genes.

In bacteria there is one general TF, the sigma factor, with different variants.

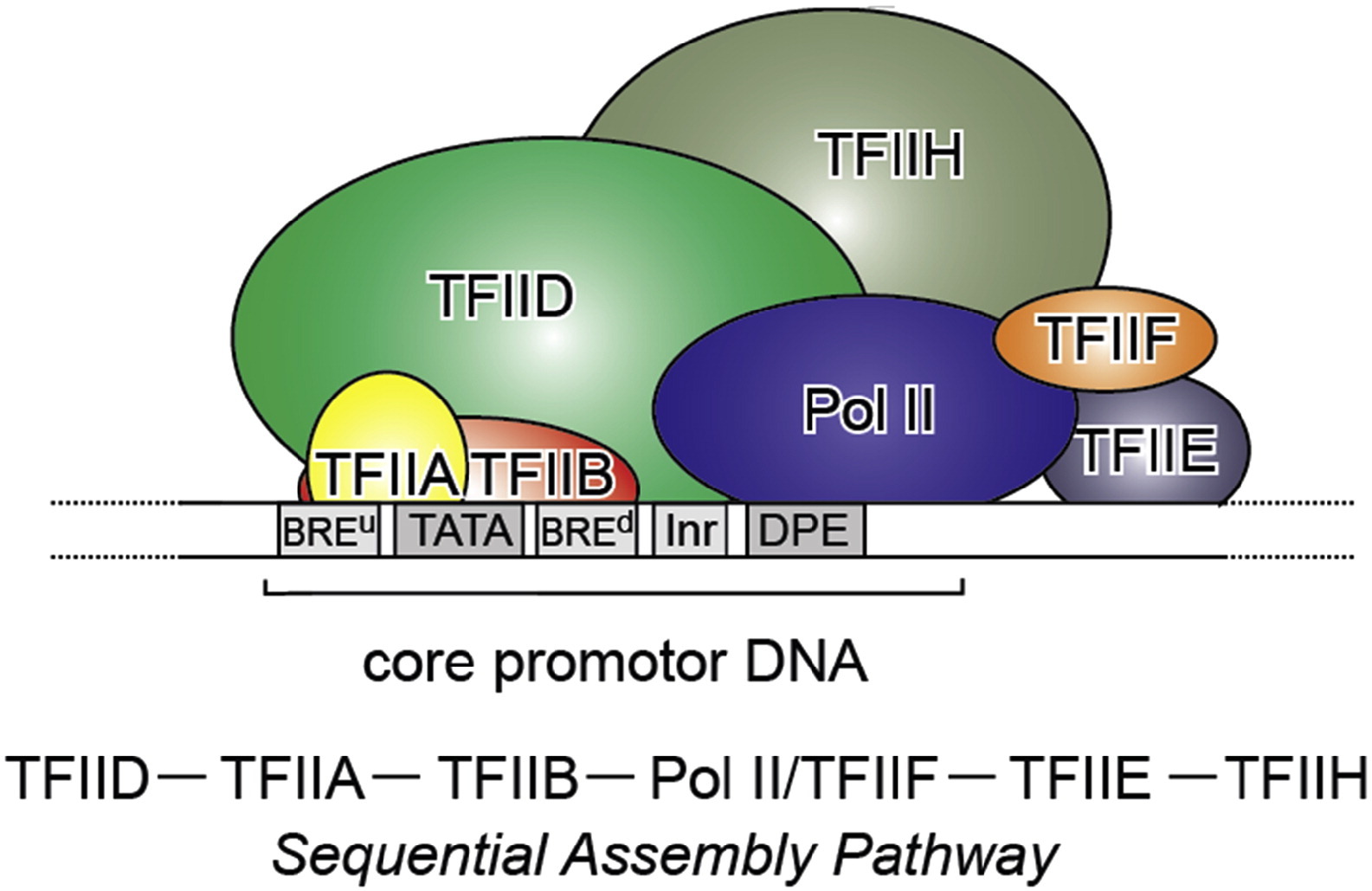

In archaea and in eukaryotes there are a few. In eukaryotes, there are six. The first that binds to the promoter is TFIID, a multiprotein factor which includes as its core the TBP (TATA binding protein, 339 AAs in humans), plus 14 additional subunits (TAFs), the biggest of which, TAF1, is 1872 AA long in humans. Four more general TFs bind sequencially the promoter. The sixth, TFIIA, is not required for basal transcription, but can stabilize the complex.

So, the initiation complex, bound to the promoter, is essentially made by RNA Pol II (or other) + the general TFs.

The following is a good review of the assembly of the initiation complex at the promoter:

Structural basis of transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II (paywall)

I quote here the conclusions of the paper:

Conclusions and perspectives

The initiation of transcription at Pol II promoters is a very complex process in which dozens of polypeptides cooperate to recognize and open promoter DNA, locate the TSS and initiate pre-mRNA synthesis. Because of its large size and transient nature, the study of the Pol II initiation complex will continue to be a challenge for structural biologists. The first decade of work, which started in the 1990s, provided structures for many of the factors involved and several of their DNA complexes. The second decade of research provided structural information on Pol II complexes and led to models for how general transcription factors function. Over the next decade, we hope that a combination of structural biology methods will resolve many remaining questions on transcription initiation, and elucidate the mechanism of promoter opening and initial RNA synthesis, the remodelling of the transient protein–DNA interactions occurring at various stages of initiation, and the conformational changes underlying the allosteric activation of initiation and the transition from initiation to elongation. Important next steps include more detailed structural characterizations of TFIIH and the 25-subunit coactivator complex Mediator, not only in their free forms but also as parts of initiation complexes.

For the Mediator, see next section.

And here is another good paper about that:

Zooming in on Transcription Preinitiation

which has a very good Figure summarizing it:

Fig. 3: From Kapil Gupta, Duygu Sari-Ak, Matthias Haffke, Simon Trowitzsch, Imre Berger: Zooming in on Transcription Preinitiation, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2016.04.003 Creative Commons license

Transcription PIC. Class II gene transcription is brought about by (in humans) over a hundred polypeptides assembling on the core promoter of protein-encoding genes, which then give rise to messenger RNA. A PIC on a core promoter is shown in a schematic representation (adapted from Ref. [5]). PIC contains, in addition to promoter DNA, the GTFs TFIIA, B, D, E, F, and H, and RNA Pol II. PIC assembly is thought to occur in a highly regulated, stepwise fashion (top). TFIID is among the first GTFs to bind the core promoter via its TBP subunit. Nucleosomes at transcription start sites contribute to PIC assembly, mediated by signaling through epigenetic marks on histone tails. The Mediator (not shown) is a further central multiprotein complex identified as a global transcriptional regulator. TATA, TATA-box DNA; BREu, B recognition element upstream; BREd, B recognition element downstream; Inr, Initiator; DPE, Down-stream promoter element.

The Mediator complex

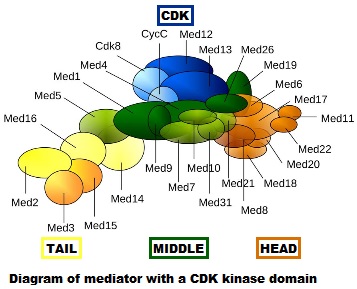

The Mediator complex is the third “general” component of transcription initiation, together with RNA Pol II and the general TFs. However, it is a really amazing structure for many specific reasons.

- First of all, it is really, really complex. It is a multiprotein structure which, in metazoan, is composed of about 25 different subunits, while it is slightly “simpler” in yeast (up to 21 subunits). Here is a very simplified scheme of the structure:

Fig. 4: Diagram of mediator with cyclin-dependent kinase module. By original figure: Tóth-Petróczy Á, Oldfield CJ, Simon I, Takagi Y, Dunker AK, Uversky VN, et al.editing: Dennis Pietras, Buffalo, NY, USA [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mediator4TC.jpg

- Second, and most important, is the fact that, while it is certainly a “general” factor, because it is involved in the transcription of almost all genes, its functions remain still poorly understood, and it is very likely that it works as an “integrration hub” which transmits and modulates many gene-specific signals (for example, those from specific TFs) to the initiation complex. In that sense, the name “mediator” could not be more appropriate: a structure which mediates between the general complex transcription mechansim and the even more complex regulatory signals coming from the enhancer-specific TFs network, and probably from other sources.

- Third, this seems to be an essentially eukaryotic structure, while RNA POL II, TFs, promoters and enhancers, while reaching their full complexity only in eukaryotes, are in part based on functions already present in prokaryotes. The proteins that make the Mediator structure seem to be absent in prokaryotes (as far as I can say, I have checked only a few of them). Moreover, many of them show a definite information jump in vertebrates, as we have seen in important regulatory proteins.

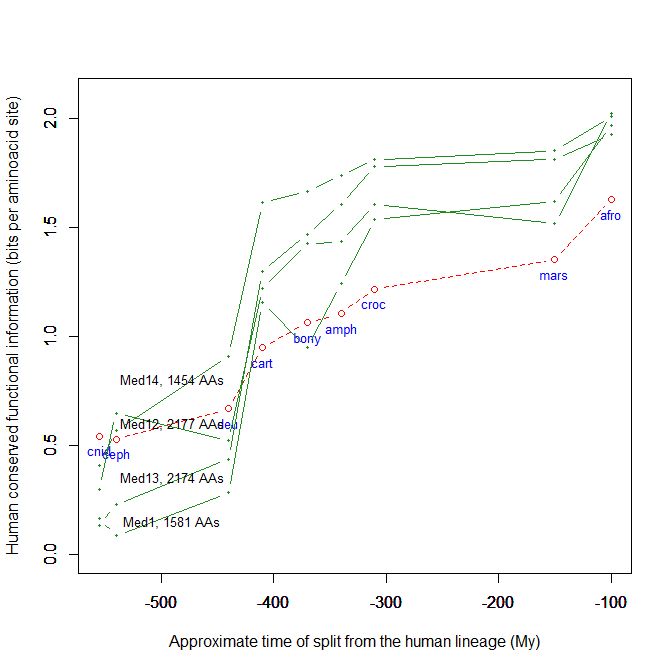

Fig. 5 shows, for example, the evolutionari history of 4 of the biggest proteins in the Mediator complex, in terms, as usual, of human conserved information. The big information jump in vertebrates is evident in all of them.

Fig. 5

Here is a paper (2010) about Mediator and its functions:

The metazoan Mediator co-activator complex as an integrative hub for transcriptional regulation

Abstract:

The Mediator is an evolutionarily conserved, multiprotein complex that is a key regulator of protein-coding genes. In metazoan cells, multiple pathways that are responsible for homeostasis, cell growth and differentiation converge on the Mediator through transcriptional activators and repressors that target one or more of the almost 30 subunits of this complex. Besides interacting directly with RNA polymerase II, Mediator has multiple functions and can interact with and coordinate the action of numerous other co-activators and co-repressors, including those acting at the level of chromatin. These interactions ultimately allow the Mediator to deliver outputs that range from maximal activation of genes to modulation of basal transcription to long-term epigenetic silencing.

Fig. 2 in the paper gives a more detailed idea of the general structure of the complex, with its typical section, head, middle, tail, and accessories.

This more recent paper (2015) is a good review of what is known about the Mediator complex, and strongly details the evidence in favor of its key role in integrating regulation signals (especially from enhancers and specific TFs) and delivering those signals to the initiation complex.

The Mediator complex: a central integrator of transcription

In Box 3 of that paper you can find a good illustration of the pre-initiation complex, including Mediator. Fig. 3 is a simple summary of the main actors in transcription, and it introduces also thet looping created by the interaction between enhancers/specific TFs on one part, and promoter/initiation complex on the other, that we are going to discuss next. It also introduces another important actor, cohesin, which will also be discussed.

Finally, this very recent paper (2018) is an example of the functional relevance of Mediator, as shown by its involvement in human neurologic diseases:

Abstract:

MED12 is a member of the large Mediator complex that controls cell growth, development, and differentiation. Mutations in MED12 disrupt neuronal gene expression and lead to at least three distinct X-linked intellectual disability syndromes (FG, Lujan-Fryns, and Ohdo). Here, we describe six families with missense variants in MED12 (p.(Arg815Gln), p.(Val954Gly), p.(Glu1091Lys), p.(Arg1295Cys), p.(Pro1371Ser), and p.(Arg1148His), the latter being first reported in affected females) associated with a continuum of symptoms rather than distinct syndromes. The variants expanded the genetic architecture and phenotypic spectrum of MED12-related disorders. New clinical symptoms included brachycephaly, anteverted nares, bulbous nasal tip, prognathism, deep set eyes, and single palmar crease. We showed that MED12 variants, initially implicated in X-linked recessive disorders in males, may predict a potential risk for phenotypic expression in females, with no correlation of the X chromosome inactivation pattern in blood cells. Molecular modeling (Yasara Structure) performed to model the functional effects of the variants strongly supported the pathogenic character of the variants examined. We showed that molecular modeling is a useful method for in silico testing of the potential functional effects of MED12 variants and thus can be a valuable addition to the interpretation of the clinical and genetic findings.

By the way, Med12 is one of the 4 proteins shown in Fig. 5 in this OP: it is 2177 AAs long, and exhibits a huge information jump in vertebrates.

Specific TFs

OK, let’s abandon, for the moment, the promoter and its initiation complex, and consider what happens at the distant enhancer site. Here, in some apparently unrelated place in the genome, which can be even 1 Mbp away, sometimes even on other chromosomes, the enhancer/specific TFs interaction takes place.

Now, we have already seen the general TFs that work at the promoter site. However fascinating, they are 6 in total (in metazoa).

But what about specific TFs?

Specific TFs are the molecules that are the true center of transcription regulation: they are the main regulators, even if of course they act together with all the other things we have described and are going to describe.

Here is a very recent reciew (2018):

The Human Transcription Factors

Abstract:

Transcription factors (TFs) recognize specific DNA sequences to control chromatin and transcription, forming a complex system that guides expression of the genome. Despite keen interest in understanding how TFs control gene expression, it remains challenging to determine how the precise genomic binding sites of TFs are specified and how TF binding ultimately relates to regulation of transcription. This review considers how TFs are identified and functionally characterized, principally through the lens of a catalog of over 1,600 likely human TFs and binding motifs for two-thirds of them. Major classes of human TFs differ markedly in their evolutionary trajectories and expression patterns, underscoring distinct functions. TFs likewise underlie many different aspects of human physiology, disease, and variation, highlighting the importance of continued effort to understand TF-mediated gene regulation.

The paper is paywalled, but for those who can access it, I would really recommend to read it.

TFs are a very deep subject, so I will just list a few points about them that seem particularly relevant here:

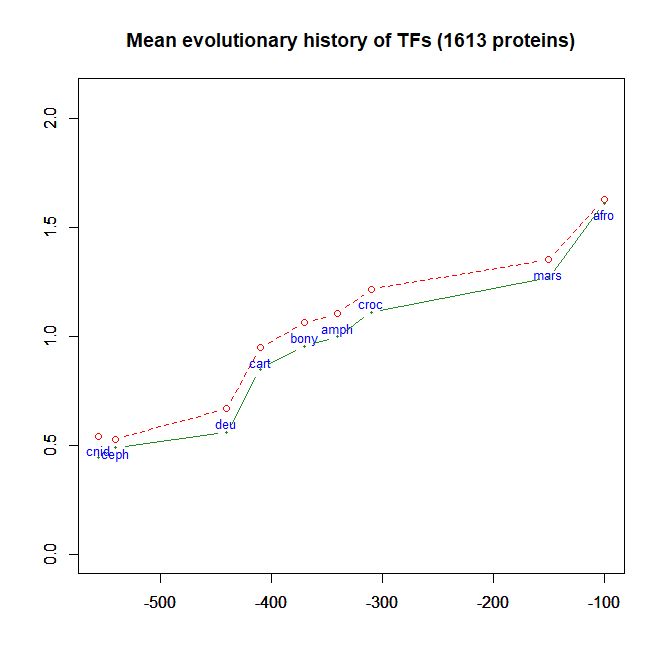

- TFs are medium sized molecules. Median length in humans, for a set of 1613 TFs derived from the paper quoted above, is 501 AAs, and 50% of those TFs are in the 365-665 AAs range.

- They are highly modular objects. In essence, almost all TFs are made of at least two components:

- A highly conserved, well recognizable domain, called the DNA binding comain (DBD), which interacts with specific, short DNA motifs (usually 6-12 nucleotides).

- DBDs can be rather easily recognized and classified in families. There are about 100 known eukaryotic DBD types. Almost all known TFs contain at least one DBD, sometimes more than one. The most represented DBD families in humans are C2H2 zinc finger (more than 700), homeodomain (almost 200) and bHLH (more than 100). DBD domains are often rather short AA sequences: zinc fingers, for example, are about 23 AAs long (but they are usually present in multiple copies in the TF), while bHLH is about 50 AAs long, and homeodomains are about 60 AAs long. As said, they are usually old and very conserved sequences.

- DNA motifs are short nucleotide sequences (6-12 nucleotides), spread all over the genome. In total, over 500 motif specificity groups are present in humans. However, motifs are not at all specific or sufficient in determinining TF binding, and many other factors must cooperate to achieve and regulate the actual binding of a TF to a DNA motif.

- At least one other sequence, which is usually longer and does not contain recognizable domains. These sequences are often highly disordered, are less conserved, and may have important regulatory functions. In some cases, other specific domains are present: for example, in the family of nuclear receptors, the TF shows, together with the DBD and the non domain sequence, a ligand domain which interacts with the hormone/molecule that conveys the signal.

- A highly conserved, well recognizable domain, called the DNA binding comain (DBD), which interacts with specific, short DNA motifs (usually 6-12 nucleotides).

- There are a lot of them. The above quoted paper, probably the most recent about the issue, gives a total of 1639 proteins that are known or likely TFs in humans, but the list is almost certainly not complete. It is very likely that there are about 2000 TFs in humans, which is about 10% of protein coding genes. Of course, all these are specific TFs (except for the 6 general TFs mentioned earlier). So, this is probably the biggest regulatory network in the cell.

- The way they work is still poorly understood, except of course for the DNA binding. It is rather certain that they usually work in groups, combinatorially, and by recruiting also other (non TF) proteins or molecules. The above mentioned paper lists many possible mechanisms of action and regulation for TF activity:

- Cooperative binding: TFs often aid each other in binding to DNA: that can imply also forming homodimers or higher order structures.

- Interaction and competition with nucleosomes, in some cases by recruiting ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers and other TFs

- Recruiting of cofactors (‘‘coactivators’’ and ‘‘corepressors’’) which are frequently large multi-subunit protein complexes or multi-domain proteins that regulate transcription via several mechanisms. The ligand-binding domains of nuclear hormone receptor subclass of TFs. already quoted before, are a special case of that.

- Exploiting unstructured regions and/or DBDs to interact with cofactors

- It is also wrong to classify individual TFs as “activators” or “repressors” I quote from the paper: Because effects on transcription are so frequently context dependent, more precise terminology may be warranted, in general— for example, reflecting the biochemical activities of TFsand their cofactors. On a global level, however, there is no comprehensive catalog of cofactors recruited by TFs. Moreover, the biochemical functions required for gene activation orcommunication between enhancers and promoters remain largely unknown

- As a class, their evolutionary history in terms of human conserved information is well comparable to thne mean pattern of the whole human genome. In particular, they do not ehibit, as a class, any special information jump in vertebrates (mean = 0.293 baa in TFs vs 0.288 baa in the whole human proteome).

Fig. 6 shows the mean evolutionary history of 1613 human TFs, in terms of baa of human conserved information, as compared to the mean values for the whole human proteome:

So, in brief: one of more specific TFs bind some specific enhancer in some part of the genome, and the specific big structure at the enhancer (enhancer + specific TFs + cofactors) in some way binds the general big structure at the promoter (promoter + RNA Pol II + general TFs + Mediator), and, probably acting on the Mediator complex, regulates the activity of the RNA polymerase and therefore the rate of transcription.

The interaction between a distant enhancer and the promoter has one important and immediate consequence: the chromatin fiber bends, and forms a specific loop (Fig. 7):

Fig. 7: Diagram of gene transcription factors

By Kelvin13 [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Transcription_Factors.svg

And, just as a final bonus about trans regulation of transcription, guess what is implied too? Of course, long non coding RNAs! See here:

Noncoding RNAs: Regulators of the Mammalian Transcription Machinery

Abstract

Transcription by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is required to produce mRNAs and some noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) within mammalian cells. This coordinated process is precisely regulated by multiple factors, including many recently discovered ncRNAs. In this perspective, we will discuss newly identified ncRNAs that facilitate DNA looping, regulate transcription factor binding, mediate promoter-proximal pausing of Pol II, and/or interact with Pol II to modulate transcription. Moreover, we will discuss new roles for ncRNAs, as well as a novel Pol II RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity that regulates an ncRNA inhibitor of transcription. As the multifaceted nature of ncRNAs continues to be revealed, we believe that many more ncRNA species and functions will be discovered.

Finally, we have to consider the role of chromatin states.

Chromatin states and epigenetics

Chromatin accessibility

For all those things to happen, one condition must be satisfied: the DNA sequences implied, IOWs the gene, promoter and specific enhancers, must be reasonably accessible.

The point is that chromatin in interphase is in different states and different 3D configurations and different spacial distributions in the nucleus, especially in relation to the nuclear lamina. In general, heterochromatin is the condensed form, functionally inactive, and is mainly associated with the nuclear lamina (the perifephery), while euchromatin, the lightly packed and transcriptionally active form, with its trancriptional loops, is more in the center of the nucleus.

However, things are not so simple: chromatin states are not a binary condition (heterochromatin/euchromatin), and they are extremely dynamic: the general map of chromatin states is different from cell to cell, and in the same cell from time to time.

One way to measure chromatin accessibility (IOWs, to map what parts of the genome are accessible to transcription in a cell at a certain time) is to use a test that directly binds or marks in some way the accessible regions. There are many such tests, and the most commonly used are DNase-seq (DNase I cuts only at the level of accessible chromatin) and ATAC-seq (insertions by the Tn5 transposon are restricted to accessible chrmatin). ATAC-seq has also been applied at the single cell level, and the results are described in this wonderful paper:

A Single-Cell Atlas of In Vivo Mammalian Chromatin Accessibility

Summary:We applied a combinatorial indexing assay, sci-ATAC-seq, to profile genome-wide chromatin accessibility in ∼100,000 single cells from 13 adult mouse tissues. We identify 85 distinct patterns of chromatin accessibility, most of which can be assigned to cell types, and ∼400,000 differentially accessible elements. We use these data to link regulatory elements to their target genes, to define the transcription factor grammar specifying each cell type, and to discover in vivo correlates of heterogeneity in accessibility within cell types. We develop a technique for mapping single cell gene expression data to single-cell chromatin accessibility data, facilitating the comparison of atlases. By intersecting mouse chromatin accessibility with human genome-wide association summary statistics, we identify cell-type-specific enrichments of the heritability signal for hundreds of complex traits. These data define the in vivo landscape of the regulatory genome for common mammalian cell types at single-cell resolution.

Epigenetic states

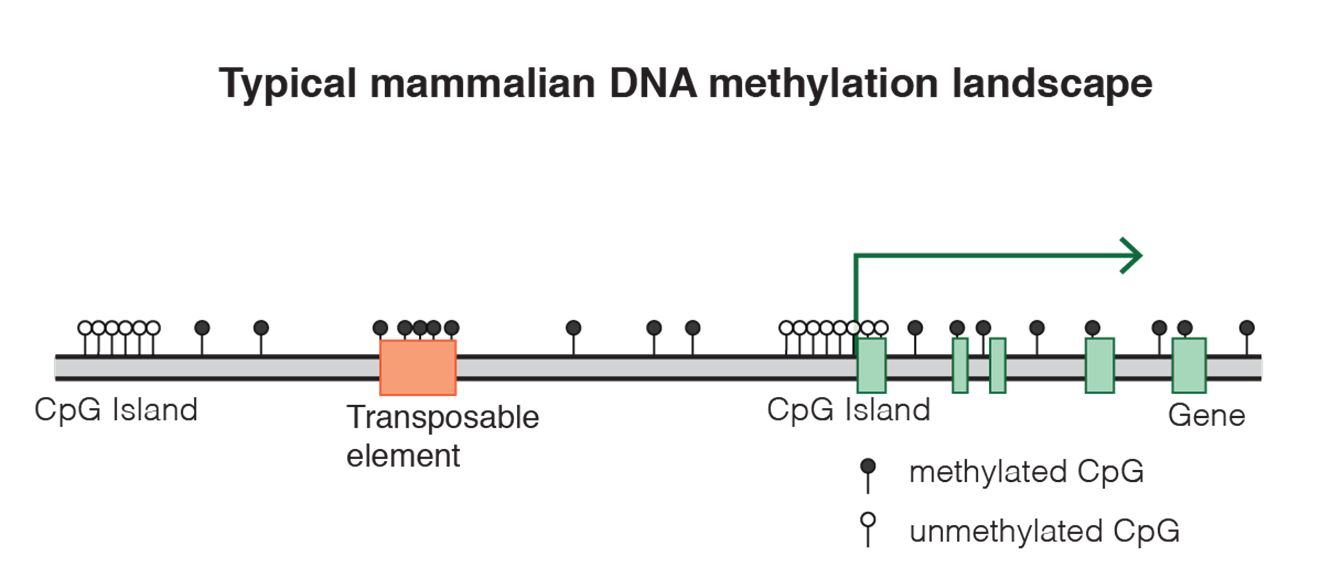

Fig. 8 DNA methylation landscape By Mariuswalter [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DNAme_landscape.png

uses 9 different histone marks, 5 methilations and 2 acetylations of histone H3, 1 methylation of histone H4 andthe mapping of CTCF (see later) to map 30 different states in the genome of 3 different types of human cells. For example, you can see in Figure 2a the 30 states (N1-30) and the 14 known transcriptional states that they are related to (the color code on the left). So, for example, state N8, which corresponds to the brown color code of “poised enhancer“, is marked by high expression of H3K27me3 (IOWs trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3) and low expression of H4K20me1 (IOWs monomethylation of lysine 20 on histone H4). The first modification has a meaning of transcriptional repression, while the second is a marker of transcriptional activation. IOWs, these nucleosomes are pre-activated, but “poised”. A similar situation can be observed in state N7, corresponding to “bivalent promoter“, where the repressive mark of H3K27me3 is associated to mono, di and trimethylation of lysine 4, always on histone H3, which are activating signals. These bivalent conditions, both for promoters and enhancers, are usually found in stem cells, where many genes are in a “pre-activated state”, momentarily blocked by the repressive signal, but ready to be activated for differentiation.

This is just to give an idea. So, this kind of analysis can well predict some of the results of the already mentioned Chromatin accessibility tests, and is also well related to the investigation of chromatin 3D configurations, which we will discuss in next section.

The following video is a good and simple review of the main aspects of the histone code.

But how are these histone modifications achieved?

Again, each of them is the result of very complex pathways, many of them still poorly understood.

For example, H3K4me3, one of the main activating marks, is achieved by a very complex multi-protein complex, involving at least 10 different proteins, some of them really big (for example, MLL2, 5537 AAs long). Moreover, the different pathways that implement different marks obviously exhibit complex crosstalks, creating intricate networks. Moreover, those pathways are not only writers of histone marks, but also readers of them: indeed, the modifictions effected are always determining by the reading of already existing modification. And, of course, there ae also eraser proteins.

All these concepts are dealed in some detail in the following paper:

The interplay of histone modifications – writers that read

A final and important question is: how do histone modifications implement their effects, IOWs the chromatin modifications that imply activation or repression of the genes? Unfortunately, this is not well understood. But:

- For some modificaions, especially acetylation, part of the effect can probably be ascribed to the direct biochemiacal effect of the modification on the histone itself

- Most effects, however, are probably implemented thorugh the recruitement by the histone modification, often in combinatorial manner, of other “reader” proteins, who are responsible, directly or indirectly, of the activation or repression effect

The second modality is the foundation for the concept of histone code: in that sense, histone marks work as signals of a symbolic code, whose effects in most cases are mediated by complex networks of proteins which can write, read or erase the signals.

3D configuration of Chromatin

As said, one the final effects of epigenetic markers, either DNA methylation or histone modifications, is the chenge in 3D configuration of chromatin, which in turn is related to chromatin accessibility and therefore to transcription regulation.

This is, again, e very deep and complex issue. There are specific techniques to study chromatin configuration in space, which are independent from the mapping of chromatin accessibility and of epigenetic markers that we have already discussed. The most used are chromosome conformation capture(3C) and genome-wide 3C(Hi-C). Essentially, these techniques are based on specific procedures of fixation and digestion of chromatin that preserve chromatin loops and allow to analyze them and therefore the associations between distant genomic sites (IOWs, enhancer promoter associations) in specific cells and in specific cell states.

Again to make it brief, chromatin topology depends essentially on at least two big factors:

- The generation of specific loops throughout the genome because of enhancer-promoter associations

- The interactions of chromatin with the nuclear lamina

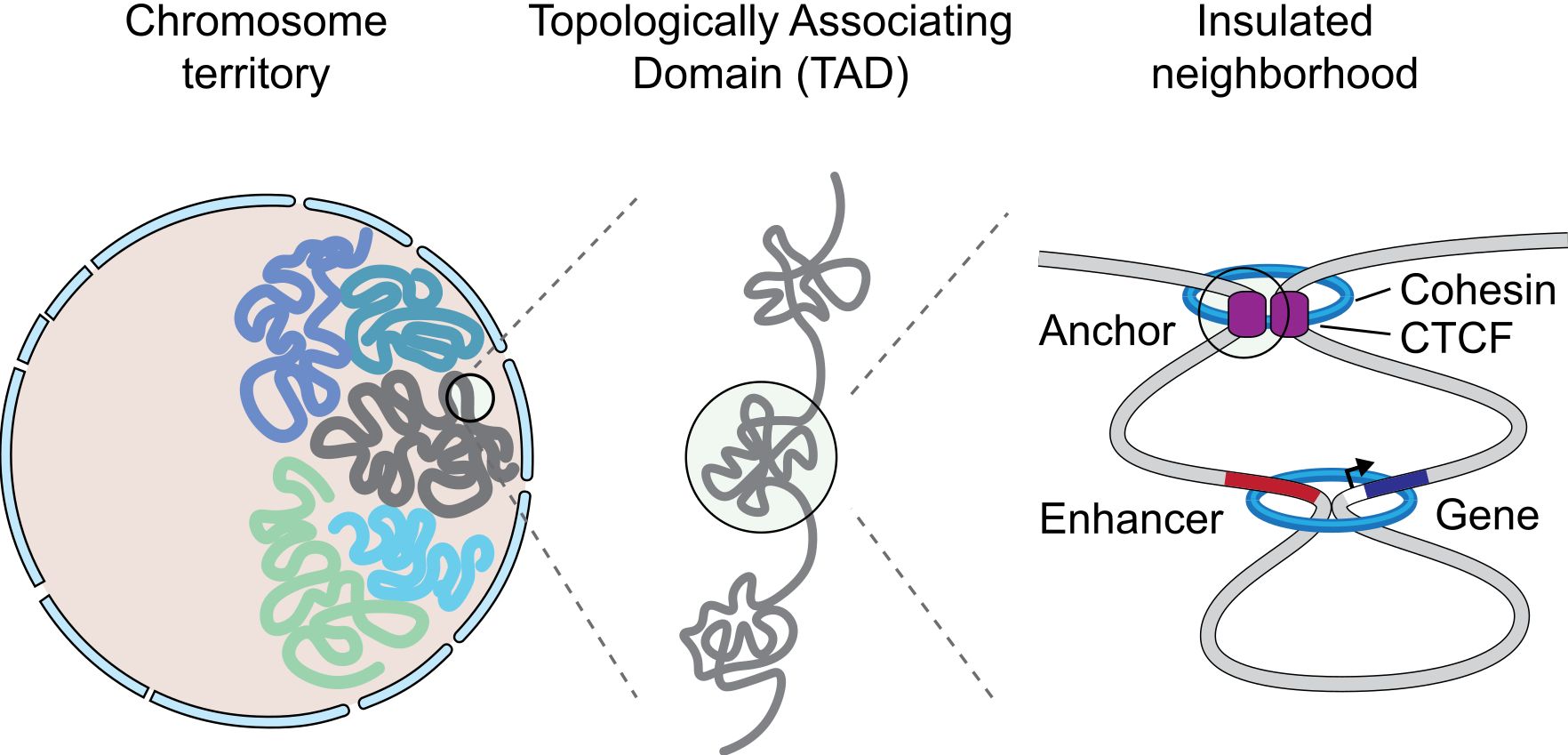

As a result of those, and other, factors, chromatin generates different levels of topologic organiazion, which can be described, in a very gross simplification, as follows, going from simpler to more complex structures:

- Local loops

- Topologically associating domains (TADs): This are bigger regions that delimit and isolate sets of specific interation loops. They can correspond to the idea of isolated “trancription factories”. TADs are separated, at genomic level, by specific insulators (see later)

- Lamina associated domains (LADs and Nucleolus associated domains (NADs): these correspond usually to mainly inactive chromatin regions

- Chromosomal territories, which are regions of the nucleus preferentially occupied by particular chromosomes

- A and B nuclear compartments: at higher level, chromatin in the nucleus seems to be divied into two gross compartments: the A compartment is mainly formed by active chrmain, the B compartment by repressed chromatin

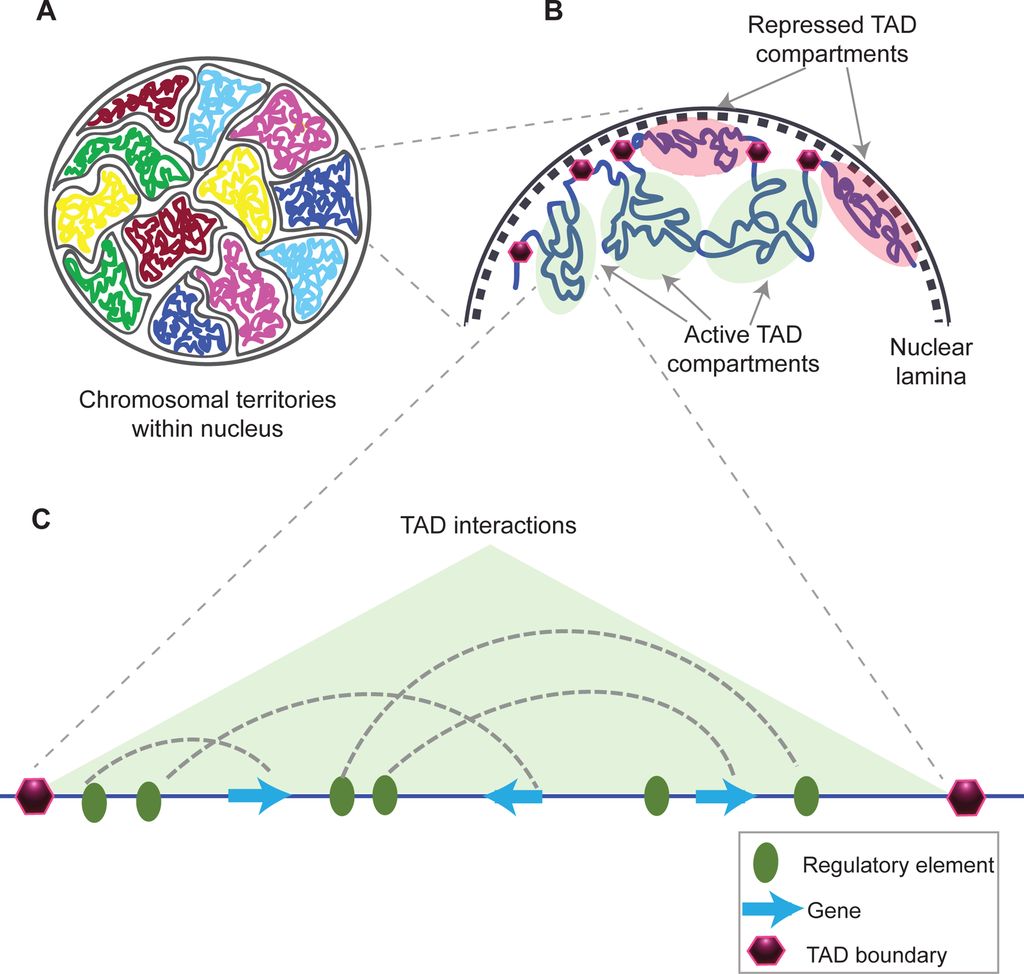

Figure 9 shows a simple representation of some of these concepts.

Fig. 9 A graphical representation of an insulated neighborhood with one active enhancer and gene with corresponding enhancer-gene loop and CTCF/cohesin anchor loop. By Angg!ng [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:InsulatedNeighborhood.svg

The concept of TAD is particularly interesting, because TADs are insulated units of transcription: many different enhancer-promoter interactions (and therefore loops) can take place inside a TAD, but not usually between one TAD and another one. This happens because TADs are separated by strong insulators.

A very good summary about TADs can be found in the following paper:

This is taken from Fig. 1 in that paper, and gives a good idea of what TADs are:

Fig. 10: Structural organization of chromatin

(A) Chromosomes within an interphase diploid eukaryotic nucleus are found to occupy specific nuclear spaces, termed chromosomal territories.

(B) Each chromosome is subdivided into topological associated domains (TAD) as found in Hi-C studies. TADs with repressed transcriptional activity tend to be associated with the nuclear lamina (dashed inner nuclear membrane and its associated structures), while active TADs tend to reside more in the nuclear interior. Each TAD is flanked by regions having low interaction frequencies, as determined by Hi-C, that are called TAD boundaries (purple hexagon).

(C) An example of an active TAD with several interactions between distal regulatory elements and genes within it.Source: Matharu, Navneet (2015-12-03). “Minor Loops in Major Folds: Enhancer–Promoter Looping, Chromatin Restructuring, and Their Association with Transcriptional Regulation and Disease“. PLOS Genetics 11 (12): e1005640. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005640. PMID 26632825. PMC: PMC4669122. ISSN 1553-7404.

Author: Navneet Matharu, Nadav Ahituv

By Navneet Matharu, Nadav Ahituv [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

There is, of course, a good correlation between the three types of anaysis and genomic mapping that we have described::

- Chromatin accessibility mapping

- Epigenetic marks

- Chromatin topology studies

However, these three approaches are different, even if strongly related. They are not measuring the same thing, but different things that contribute to the same final scenario.

CTCF and Cohesin

But what are these insulators, the boundaries that separate TADs one from another?

While the nature of insulators can be complex and varies somewhat from species to species, in mammals the main proteins responsible for that function are CTCF and cohesin.

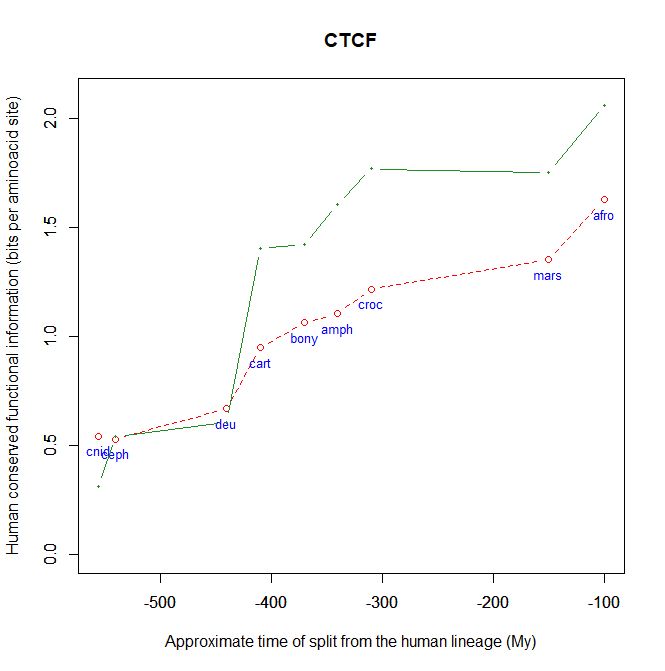

CTCF is indeed a TF, a zinc finger protein with repressive functions. While it has other important roles, it is the major marker of TAD insulators in mammals. It is 727 AAs long in humans, and its evolutionary history shows a definite information jump in vertebrates (0.799 baa, 581 bits) as shown in Fig. 5, which is definitely uncommon for a TF.

We have already encountered CTCF as one of the epigenetic markers used in histone code mapping. Its importance in transcription regulation and in many other important cell functions cannot be overemphasized.

Cohesin is a multiprotein complex which forms a ring around the double stranded DNA, and contributes to a lot of important stabilizations of the DNA fiber in different situations, especially mitosis and meiosis. But we know now that it is also a major actor in insulating TADs, as can be seen in Fig 4, and in regulating chromatin topology. Cohesin and its interacting proteins, like MAU2 and NIPBL, are a fascinating and extremely complex issue of their own, so I just mention them here because otherwise this already too long post would become unacceptably long. However, I suggest here a final, very recent review about these issues, for those interested:

Forces driving the three‐dimensional folding of eukaryotic genomes

Abstract:

The last decade has radically renewed our understanding of higher order chromatin folding in the eukaryotic nucleus. As a result, most current models are in support of a mostly hierarchical and relatively stable folding of chromosomes dividing chromosomal territories into A‐ (active) and B‐ (inactive) compartments, which are then further partitioned into topologically associating domains (TADs), each of which is made up from multiple loops stabilized mainly by the CTCF and cohesin chromatin‐binding complexes. Nonetheless, the structure‐to‐function relationship of eukaryotic genomes is still not well understood. Here, we focus on recent work highlighting the biophysical and regulatory forces that contribute to the spatial organization of genomes, and we propose that the various conformations that chromatin assumes are not so much the result of a linear hierarchy, but rather of both converging and conflicting dynamic forces that act on it.

Summary and Conclusions

So this is the part where I should argue about how all the things discussed in this OP do point to design. Or maybe I should simply keep silent in this case. Because, really, there should be no need to say anything.

But I will. Because, you know, I can already hear our friends on the other side argue, debate, or just suggest, that there is nothing in all these things that neo-darwinism can’t explain. They will, they will. Or they will just keep silent.

So, I will briefly speak.

First of all, a summary of what has been said. I will give it as a list of what really happens, as far as we know, each time that a gene starts to be transcribed in the appropriate situation: maybe to contribute to the differentiation of a cell, maybe to adjust to a metabolic challenge, or to anything else.

- So, our gene was not transcribed, say, “half an hour ago”, and now it begins to be transcribed. What has happened ot effect this change?

- As we know, first of all some specific parts of DNA that were not active “half an hour ago” had to become active. At the very least, the gene itself, its promoter, and one appropriate enhancer. Therefore, some specific condition of the DNA in those sites must have changed: maybe through changes in histone marks, maybe through chromatin remodeling proteins, maybe through some change in DNA methylation, maybe through the activity of some TF, or some multi-protein structure made by TFs or other proteins, maybe in other ways. What we know is that, whatever the change, in the end it has to change some aspects of the pre-existing chromatin state in that cell: chromatin accessibility, nucleosome distribution, 3D configuration, probably all of them. Maybe the change is small, but it must be there. In our Fig. 2 (at the beginning of this long post) the red arrows are therefore acting from left to right, to effect a transition from state 1 to state 2.

- So, the appropriate DNA sequences are now accessible. What happens then?

- At the promoter, we need at least that the multiprotein structure formed by our 6 general TFs and the multiprotein structure that is RNA Pol II bind the promoter. See Figure 3.

- Always at the promoter, the huge multiprotein structure which is the Mediator complex must join all the rest. See Figure 4.

- At the enhancer, one or more specific TFs must bind the appropriate motif by the appropriate DBD, interact one with the other, recruit possible co-factors.

- At this point, the structure bound at the enhancer must interact with the distant structure at the promoter, probably through the Mediator complex, generating a new chromatin loop, usually in the context of the same TAD. see Fig. 7.

- So, now the 3D configuration of chromatin has changed, and transcription can start.

- But as the new protein is transcribed, and then probably translated (through many further intermediate regulation steps, of course, like the Spliceosome and all the rest), the transcriptome/proteome is changing too. In many cases, that will imply changes in factors that can act on chromatin itself, for example if the new protein is a TF, or any other protein implied directly or indirectly in the above described processes, or even if it can in some way generate new signals that will in the end act on transcription regulation. Maybe the change is small, but it must be there. In our Fig. 2 (at the beginning of this long post) the red arrows are now probably acting from right to left, possibly initiating a transition from state 2 to state 3.

- After all, that is what must have happened at the beginning of this sequence, when some new condition in the transcriptome/proteome started the transcription of our new protein.

And now, a few considerations:

- This is just an essential outline: what really happens is much, much more complex

- As we have seen, the working of all this huge machinery requires a lot of complex and often very specific proteins. First of all the 2000 specific TFs, and then the dozens, maybe hundreds, of proteins that implement the different steps. Many of which are individually huge, often thousands of AAs long.

- The result of this machinery and of its workings is that thousands of proteins are transcribed and translated smoothly at different times and in different cells. The result is that a stem cell is a stem cell, a hepatocyte a hepatocyte and a lymphocyte a lymphocyte. IOWs, the miracle of differentiation. The result is also that liver cells, renal cells, blood cells, after having differentiated to their “stable” state, still perform new wonders all the time, changing their functional states and adapting to all sorts of necessities. The result is also that tissues and organs are held together, that 10^11 neurons are neatly arranged to perform amazing functions, and so on. All these things rely heavily on a correct, constant control of transcription in each individual cell.

- This scenario is, of course, irreducibly complex. Sure, many individual components could probably be shown not to be absolutely necessary for some rough definition of function: transcription can probably initiate even in the absence of some regulatory factor, and so on. But the point is that the incredibly fine regulation of the whole process, its management and control, certainly require all or almost all the components that we have described here.

- Beyond its extraordinary functional complexity, this regulation network also uses at its very core at least one big sub-network based on a symbolic code: the histone code. Therefore, it exhibits a strong and complex semiotic foundation.

So, the last question could be: can all this be the result of a neo-darwinian process of RV + NS of simple, gradual steps?

That, definitely, I will not answer. I think that everybody already knows what I believe. As for others, everyone can decide for themselves.

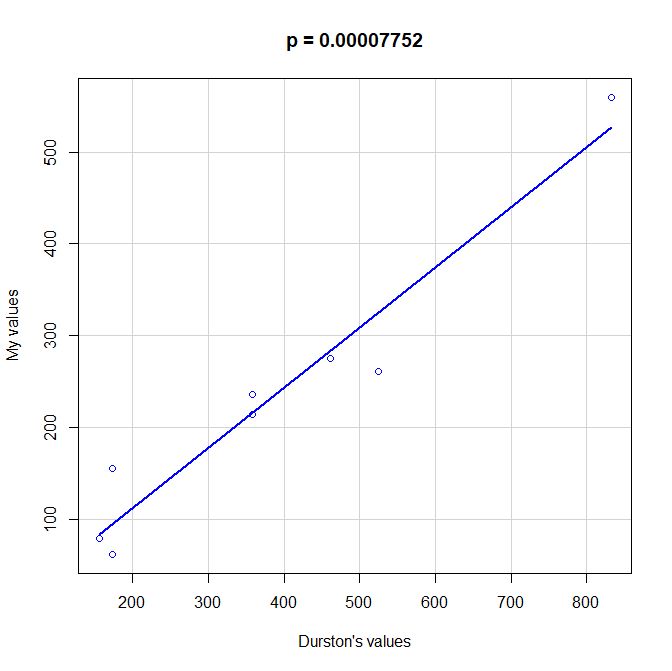

PS: Here is a scatterplot of some values of functional information obtained by my method as compared to the values given by Durston, as per request of George Castillo. As can be seen, the correlation is quite good, even with all the difficulties in comparing the two methods, that are quite different under many aspects. However, my method definitely underestimates functional information as compared to Durston’s (or vice versa).

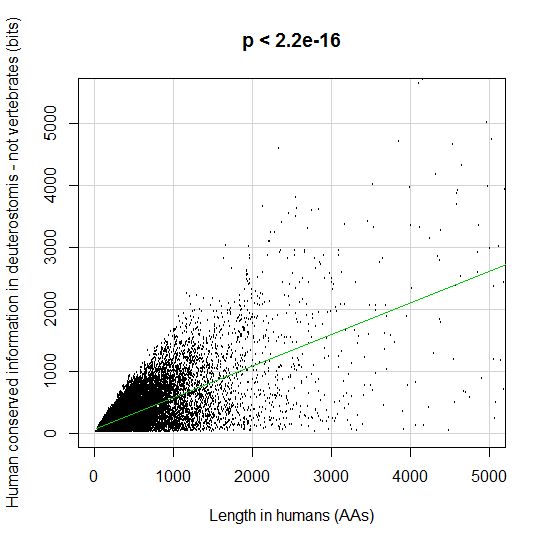

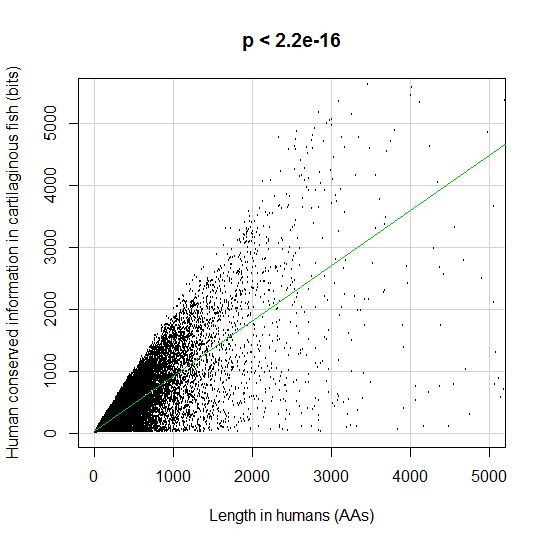

PPS: More graphs added as per request of George Castillo. The explanation in in comment #270.