Over at Why Evolution Is True, Professor Jerry Coyne has written a post mocking an anthropologist for claiming that human beings aren’t apes. Not only is Coyne’s reasoning muddle-headed, but his biology is embarrassingly wrong. Heck, even I could spot his mistakes – and I’m not a scientist.

The anthropologist who has had the temerity to declare that humans are not apes is Professor Jonathan Marks, who teaches biological anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. In an article on his PopAnth blog titled, Are we apes? No, we are humans, Marks insists that we are related to apes: “indeed,” he writes, “we are closer to a chimpanzee than that chimpanzee is to an orangutan” and “we know that our DNA is over 98% identical to that of a chimpanzee” – but he goes on to argue that “ancestry is not the same as identity.” Marks acknowledges that we fall phylogenetically within the group that we call “apes,” but he points out that we also fall phylogenetically within the group that we call “fish” – and yet nobody would think of calling us fish. “To call us ‘apes’ or ‘fish’ because our ancestry resides among those organisms is a trivial statement about how those categories are artificially constructed, not a profound revelation about our natural identity,” writes Marks.

(All emphases below are mine – VJT.)

Coyne’s embarrassing error

And it is here, in his critical review of Marks’ article, that Professor Coyne comes a cropper. In response to Marks’ argument that since a coelacanth is more closely related to us than it is to a trout, we therefore “fall within the category that encompasses both coelacanths and trout, namely, fish,” Coyne fires back:

Yes, but that’s not the same thing as saying that we fall phylogenetically with the group that we call fish. In fact we don’t (see below)…

Well, “bony fish” are in the superclass Osteichthyes, to which we don’t belong, but we do belong to the class Sarcoptrygii (sic), which are descendants of early fish, a group that include tetrapods.

The problem here is that Coyne’s own sources contradict him – and at least one senior evolutionary biologist does, as well. The Wikipedia article on Sarcopterygii, which he cites, states, “The Sarcopterygii … or lobe-finned fish … constitute a clade (traditionally a class or subclass) of the bony fish” (i.e. Osteichthyes), adding that “a strict cladistic view includes the terrestrial vertebrates” within the Sarcopterygii. The Wikipedia article on Osteichthyes confirms this by declaring that “the common ancestor of all Osteichthyes includes tetrapods amongst its descendants.” While the Osteichthyes were once considered a class, they are now regarded as a superclass, consisting of two classes: Actinopterygii, or ray-finned fishes, and Sarcopterygii, or lobe-finned fish – a group which on a strict cladistic view “includes the terrestrial vertebrates.”

So to sum up: contra Coyne, human beings do belong to the superclass Osteichthyes (bony fish) as well as the class of Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fish). Hence Marks is quite correct in saying that we fall phylogenetically with the group that we call fish – or more precisely, bony fish. Bony fish, in turn, belong to the subphylum known as vertebrates (or Vertebrata): “Vertebrates include the jawless fish and the jawed vertebrates, which includes the cartilaginous fish (sharks and rays) and the bony fish. A bony fish clade known as the lobe-finned fishes is included with tetrapods, which are further divided into amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds.”

It gets worse for poor Professor Coyne. Evolutionary biologist P.Z. Myers openly declares in Ray Comfort’s movie, Evolution vs. God, that “Human beings are still fish” (6:28). When an incredulous Ray Comfort echoes, “Human beings are fish?”, Myers calmly responds, “Why yes, of course they are.” Commenting on the interview with Ray Comfort, Myers declares that “we humans are derived fish.” Finally, in a recent post in response to Professor Jonathan Marks, Myers quotes Professor Marks’ remark:

On the other hand, we also fall phylogenetically within the group that we call “fish.” That is to say, a coelacanth is more closely related to us than it is to a trout. So we fall within the category that encompasses both coelacanths and trout, namely, fish.

and comments:

Yes! He almost has it!

He then goes on to chide Marks for “failure,” for refusing to accept this conclusion. I shall return to Myers’ arguments below. Suffice it for now to note that P.Z. Myers’ own testimony amply refutes Professor Jerry Coyne’s claim that humans are not phylogenetically classified as bony fish. Clearly, they are. As a biologist, Coyne really should have known that.

So, are we apes or not?

Marks elaborates on his argument that we are not apes, but ex-apes, in a TEDx talk (given in 2012) titled, You are not an ape! In the course of his address, Marks humorously contrasts a statement from Jerry Coyne’s best-seller, Why Evolution Is True, with a statement from evolutionist George Gaylord Simpson in his classic work, The Meaning of Evolution (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1949). Writes Coyne:

“We are apes descended from other apes, and our closest cousin is the chimpanzee, whose ancestors diverged from our own several million years ago in Africa. These are indisputable facts.”

However, Simpson declared the precise opposite:

“It is not a fact that man is an ape.”

Marks explains the apparent contradiction by pointing out that a few decades ago, back in Simpson’s day, scientists were unwilling to make the leap of logic from “Our ancestors were apes” to “We are apes,” whereas scientists today seem to be much more willing to take that step. The change has been largely driven by what Marks calls “twenty years of geno-hype” – that is, “the rhetorical excesses that accompanied the human genome project,” which have given rise to the myth that your DNA is the most important thing about you. However, a comparison of genomes, argues Marks, is a one-dimensional comparison; whereas bodies, on the other hand, are four-dimensional objects. We can’t really explain “how you make a four-dimensional body out of a one-dimensional set of instructions.” The problem here is not a technical but a conceptual one: units of heredity (genes) simply don’t map onto units of the body (e.g. elbows). Marks concludes by posing the question: “Are you just your ancestry?” – a question he answers with an emphatic “No!” We are not peasants, just because our ancestors were; and by the same token, we are not apes, just because our ancestors were. We are fundamentally different from chimpanzees, avers Marks: “We communicate differently, … and quite frankly, we’re driving them to extinction, not vice versa.” These things don’t show up in the DNA, but they’re arguably more important than the things that do show up in the DNA. While our ancestors were apes, we are ex-apes. Ultimately, the reason why the notion that we are apes has recently gained popularity, suggests Marks, is a cultural one: it gives us “one more weapon with which to bludgeon the creationists.” At the conclusion of his talk, Marks warns it’s a bad idea to be so preoccupied with attacking the creationists that you’re willing to say things that are simply wrong.

Humans and apes: What did George Gaylord Simpson actually say?

After listening to Professor Marks’ speech, the first thing I decided to check out was whether he had represented George Gaylord Simspon’s views correctly. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to access Simpson’s classic work, The Meaning of Evolution, online, but I did come across Simple Curiosity; Letters from George Gaylord Simpson to His Family, 1921-1970 (edited by Leo F. Laporte, University of California Press, 1987). In a letter to his sister, written in London in August 1927, Simpson declared himself a staunch human supremacist who considered himself infinitely above the apes, despite his embrace of evolution and his rejection of religion:

… I do get fed up with people who talk about about (sic) the degrading effect of the theory, or rather the fact, that man’s descended from the apes. The great contribution of the theory to human thought is, quite unlike what is thought, that it shows man’s infinite superiority to the lower animals. Everyone know that what we earn is more precious & less likely to be squandered than what is given to us. Our humanity, our character of being human beings, has been earned by the handicaps & battles of a hundred thousand generations. It wasn’t given to us by a gentleman in a long beard. We fought for it & it’s up to us to keep it. We aren’t poor silly weaklings who couldn’t even keep Yahweh from foreclosing his mortgage on our garden, we’re Men who’ve made ourselves such and raised ourselves above the brutes. We’re not on the way down, but on the way up. We didn’t inherit our wealth, we earned it by the sweat of our brows. Because we were once apes is the more reason for not acting like apes now that we are men. (p. 110)

So George Gaylord Simpson, who has been called the greatest paleontologist since Georges Cuvier and the most influential natural historian of the twentieth century, didn’t agree with the view that we are apes, even though he unhesitatingly affirmed that we are descended from apes.

What of Coyne’s and Myers’ arguments that we are apes?

But what, it will be asked, are we to make of Professor Jerry Coyne’s and Professor P.Z. Myers’ arguments that we are apes? Let’s look at Coyne’s arguments first:

If you look up the family Hominidae, you’ll see that it includes all the “great apes”: orangutans, chimps (both common chimps and bonobos), gorillas, and humans. In other words, we are “great apes”. We are also “hominids”, a term once used to refer to every species on “our” side of the evolutionary tree since we diverged from the ancestors of the other apes, but now hominids refers to all the hominidae, and the former “hominid” is now “hominin“. (You can see the full phylogenetic placement of our species here.) Finally, we are in the more inclusive superfamily Hominoidea, which are all apes, including the great apes and the gibbons.…

Saying that we are not apes is like saying that Drosophila are not flies (dipterans). It’s just dumb, and somehow meant to set us apart from other great apes. Yes, we do have unique traits, but we’re still in the family of hominids. And, contra Marks, that does not mean that we are our ancestors. It means we share a common ancestor that lived in the past.

There are three glaring problems with the foregoing account.

First of all, Coyne simply assumes that the family of hominids (to which humans, chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans all belong) should be called “great apes,” without providing any justification for this assumption.

The point I wish to make here is that the word “ape” is not a scientific term, but a “folk” term in our ordinary language. As such, its meaning is determined by the people who use it, rather than by a privileged class of experts. Since popular usage distinguishes human beings from apes, it follows that we are not apes.

Second, I should point out that the term “hominid” was originally defined by scientists themselves as the family to which humans belong; the great apes were placed in a separate family of their own: Pongidae. For example, my Concise Oxford Dictionary (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1990) defines the term “hominid” as “any member of the primate family Hominidae, including humans and their fossil ancestors.” No mention here of apes! This was once the customary usage of the term “hominid.” It was only when molecular evidence showed that human and chimpanzee DNA are 98% similar that scientists decided that humans and great apes should be classed in the same family. Pongidae became an obsolete primate primate taxon. Now, I would not contest for a minute that scientists had every right to reclassify humans, chimps, gorillas and orangutans in the same family: hominids. What I do deny is that scientists have the right to call this family “great apes.” That’s for the people to decide, not scientists. For it is the people who own the term “ape.”

As for “hominoids” – a term that now includes humans, great apes (chimps , gorillas and orangutans) and gibbons – the simple fact is that there never was a common name corresponding to this scientific term. Indeed, Dr. John R. Grehan, former Director of Science and Research Buffalo Museum of Science, in an article titled, “Primate Taxonomy,” in 21st Century Anthropology: A Reference Handbook (edited by H. James Birx), defines the term “hominoid” as follows: “Hominoids comprise humans, great apes, and lesser apes” (p. 620). Yet Dr. Grehan has no problem with common descent – indeed, he repeatedly affirms it in his article. Hence for Professor Coyne to equate “hominoids” with “apes” is a move that has no linguistic precedent. Once again, Coyne is displaying the impertinence of a scientist trying to mold ordinary human language into the form he thinks it should possess. He has no right to do that. Ordinary language belongs to the people. I say: let them decide what they want the term “ape” to mean.

Third, Coyne’s argument overlooks the very awkward fact that until recently, evolutionary scientists used to deny that human beings were descended from apes. Indeed, I can remember it being drummed into me by my high school science teachers, from Grade 7 onwards, that the theory of evolution does not teach that humans are descended from apes; rather, what it teaches is that humans and apes have a common ancestor. Thus PBS, in its Evolution Library, features a 2001 Web page titled, Frequently Asked Questions About Evolution: Where We Came From, which states:

1. Did we evolve from monkeys?

Humans did not evolve from monkeys. Humans are more closely related to modern apes than to monkeys, but we didn’t evolve from apes, either. Humans share a common ancestor with modern African apes, like gorillas and chimpanzees. Scientists believe this common ancestor existed 5 to 8 million years ago. Shortly thereafter, the species diverged into two separate lineages. One of these lineages ultimately evolved into gorillas and chimps, and the other evolved into early human ancestors called hominids.

The science in the above passage is a little out-of-date, as humans are now believed to be closer to chimps than gorillas are. Nevertheless, the writer of the article was well aware that humans are closer to chimps than orangutans are – and yet this fact did not cause him/her to reclassify humans as “apes.” Evidently the writer, like Professor Jonathan Marks, viewed humans as ex-apes. And why not?

Likewise, a Webpage by the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, titled, Introduction to Human Evolution (last updated 2015-11-02), states:

Humans and the great apes (large apes) of Africa — chimpanzees (including bonobos, or so-called “pygmy chimpanzees”) and gorillas — share a common ancestor that lived between 8 and 6 million years ago.

Once again, humans are distinguished from the “great apes (large apes) of Africa,” with whom they are said to share a common ancestor.

I now turn to Professor P.Z. Myers’ post. Myers quotes a lengthy passage from Jonathan Marks, pointing out the vast behavioral differences between humans and chimpanzees, as well as the fact that human cells (which have 46 chromosomes) can be readily distinguished from the cells of apes (which have 48). Myers comments:

He’s confusing species with higher levels of the taxonomic hierarchy, that is, the leaves for the branches. If he’s going to take that attitude, there are no apes anywhere — there is no single species we’d call “apes”. Chimpanzees could similarly protest that they aren’t apes, they have a set of characteristics that distinguish them from those other apes, gorillas, humans, and orangutans. Gorillas could announce that they are Gorilla gorilla gorillia (sic), not some damn dirty ape like chimps or humans or orangutans. And so on.

Of course we’re apes. We’re members of a broad group of related animals, and we call that taxonomic group the apes. What he’s doing is similar to if I declared that I’m not human, I’m an American — rejecting affiliation with a general category to claim exclusive membership to a subcategory.

What’s wrong with Myers’ first paragraph is that it assumes that all morphological changes are equal. Chimpanzees do indeed have a set of traits distinguishing them from the ancestor they share with human beings. But by any sensible measure, humans are anatomically far more unlike chimpanzees than chimpanzees are unlike gorillas or orangutans.

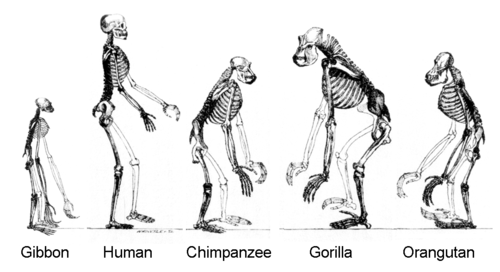

But don’t take my word for it. Here’s a picture (courtesy of Wikipedia) showing the hominoids, standing side by side. It’s pretty easy to see that humans look very dissimilar to the great apes:

|

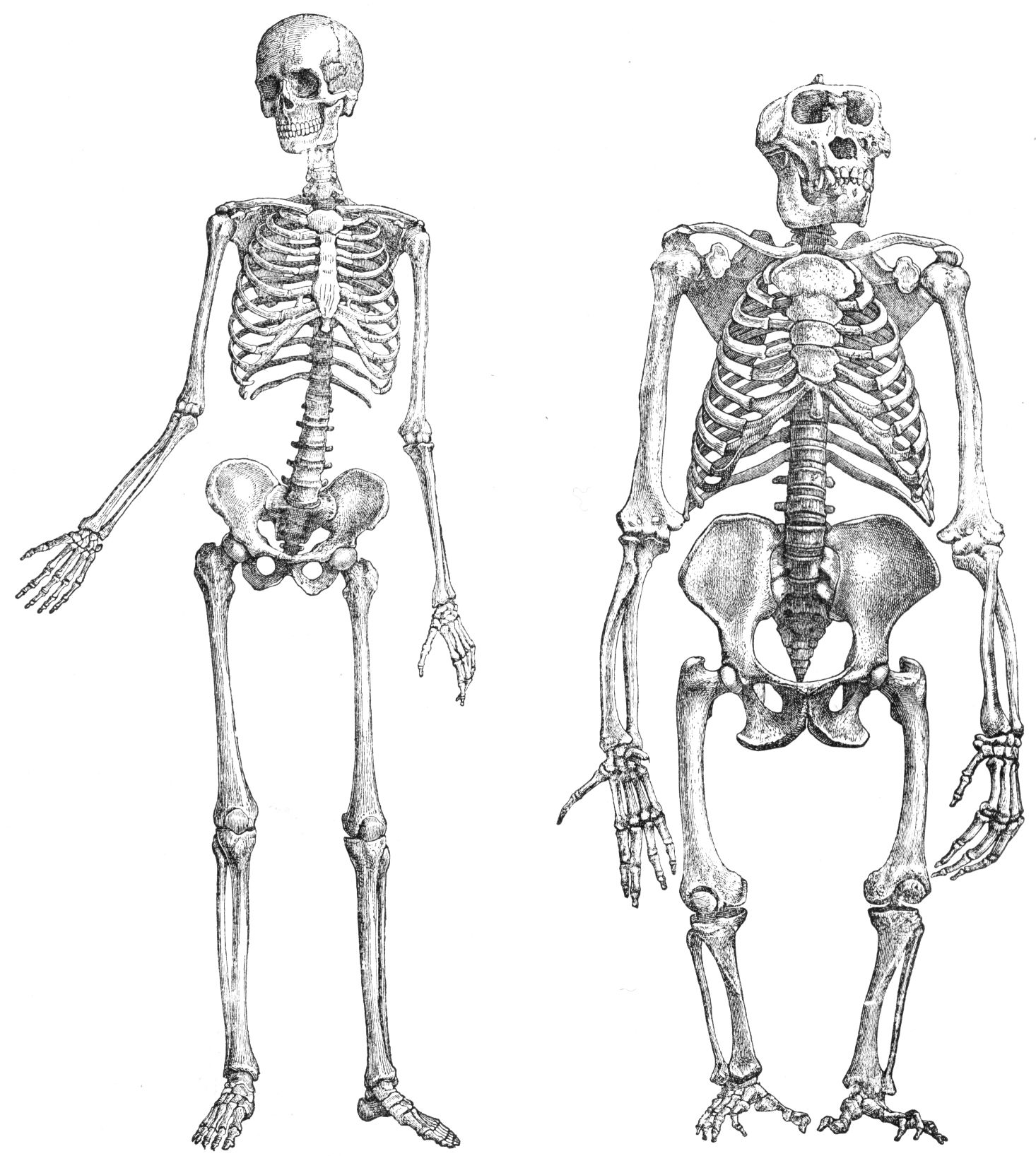

And here’s another picture, showing frontal views of a human skeleton and a gorilla skeleton. Not so similar, are they?

|

Finally, Charles Darwin himself was well aware that human beings had evolved to a much greater degree than their simian cousins, and in his Descent of Man, he wrestled with the question of how human beings out to be classified:

As far as differences in certain important points of structure are concerned, man may no doubt rightly claim the rank of a Sub-order; and this rank is too low, if we look chiefly to his mental faculties. Nevertheless, under a genealogical point of view it appears that this rank is too high, and that man ought to form merely a Family, or possibly even only a Sub-family. If we imagine three lines of descent proceeding from a common source, it is quite conceivable that two of them might after the lapse of ages be so slightly changed as still to remain as species of the same genus; whilst the third line might become so greatly modified as to deserve to rank as a distinct Sub-family, Family, or even Order. But in this case it is almost certain that the third line would still retain through inheritance numerous small points of resemblance with the other two lines. Here then would occur the difficulty, at present insoluble, how much weight we ought to assign in our classifications to strongly-marked differences in some few points, — that is to the amount of modification undergone; and how much to close resemblance in numerous unimportant points, as indicating the lines of descent or genealogy. The former alternative is the most obvious, and perhaps the safest, though the latter appears the most correct as giving a truly natural classification.

(Darwin, C. R. 1871. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray. Volume 1. 1st edition. Scanned by John van Wyhe in 2006. Chapter VI, p. 195.)

As for the assertion in Myers’ second paragraph quoted above – that Professor Marks’s argument is similar to someone’s declaring that he’s not human, but an American – Myers’ parallel argument falls flat on one very simple point: you don’t acquire any fundamentally new abilities – such as the ability to speak, perform mathematical reasoning, or remember the story of your life (none of which a chimp can do) when you become an American. Compared to the mental Rubicon we crossed in the process of becoming human – whether it happened slowly or very quickly is beside the point here – the acquisition of American citizenship is a relatively minor change.

As we have seen, Marks argues that just as I wouldn’t call myself a peasant just because my ancestors were peasants, likewise I shouldn’t call myself an ape just because my ancestors were apes. I have to say that I don’t think this argument works, either. I still share many physical traits with the apes, with whom I share a common ancestry; on this point, Myers is correct. However, as far as I can tell, I don’t share any distinctive traits with my peasant ancestors.

Finally, in response to Professor Marks’ argument that he is not a fish, because he can read and fish can’t, P.Z. Myers retorts:

Jonathan Marks: go back to school and learn some cladistics. You don’t identify a clade by autapomorphies, or traits that are novel to a species, like reading. It’s like declaring that zebrafish have horizontal stripes, and fish don’t have stripes, therefore they are not fish. It’s stupid on multiple levels.

It hardly needs pointing out that Jonathan Marks is not a cladist: he doesn’t believe in categorizing organisms based on shared derived characteristics that can be traced to a group’s most recent common ancestor. As he writes in his essay, Are we apes? No, we are humans:

We reject the simple equation of ancestry with identity in other contexts. Why should we accept it in science? The short answer is that we shouldn’t.

One reader who commented on Professor Marks’ article perceptively summed up the problem with cladistics:

Evolution is descent with modification. Cladistics emphasizes descent. But some of these modifications are so profoundly game-changing (e.g symbolic communication) that it’s useful to collectively refer to groups that lack them but share ancestral characteristics even if the group is paraphyletic (grade). For example, prokaryotes are paraphyletic but few would have a problem referring to them collectively, and fewer still would say that eukaryotes are archaea.

Since Marks disagrees so fundamentally with cladistics in its approach to human identity, Myers’ suggestion that Marks should go back to school and study it, completely misses the point. The real question is whether my identity is determined more by what happened to my ancestors before they diverged from the line leading to chimpanzees, or by what happened to my ancestors after they diverged from the chimpanzee lineage. For my part, I would wholeheartedly agree with Professor Marks that it is the latter changes that truly constitute my identity as a human being. And I think that any person of good sense would share my view.

I’ll give the last word to anthropologist John Hawks. In his 2012 article, Humans aren’t monkeys. We aren’t apes, either, he attacks what he calls the “canard” that “humans are apes”:

My children can tell what an ape is. I work very hard to tell them why apes are different than monkeys. When they see a chimpanzee in a zoo, and other parents are telling their kids, “Look at the monkey!”, my children say, “That’s not a monkey, it’s an ape!”…

Chimpanzees are apes. Gorillas are apes, as are bonobos, orangutans, and gibbons. We routinely differentiate the “great apes” from the “lesser apes”, where the latter are gibbons and siamangs. Humans are not apes. Humans are hominoids, and all hominoids are anthropoids. So are Old World monkeys like baboons and New World monkeys like marmosets. All of us anthropoids. But humans aren’t monkeys.

What’s the difference?

“Ape” is an English word. It is not a taxonomic term. English words do not need to be monophyletic. French, German, Russian, and other languages do not have to accord with English ways of splitting up animals. Taxonomy is international – everywhere, we recognize that humans are hominoids…

We shouldn’t smuggle taxonomic principles into everyday language to make a political argument. That’s what “humans are apes” ultimately is – it’s an argument that we aren’t as great as we think we are. Whether humans are special or not should be derived from biology; I don’t think we need to make the argument by applying Orwellian coercion to the meanings of English words. Biologists control taxonomic terminology, and that’s where science should aim. I don’t think I’m being old-fashioned, nor am I promoting the idea that humans aren’t part of the primate phylogeny. I’m only promoting the idea that we use taxonomy for its intended purpose, and not insist that English do the job instead.

We aren’t apes. And it’s OK to teach your children that chimpanzees are apes, not monkeys. Because that’s what I do.

What do readers think?