|

|

The atheist blog Ungodly News has just released a Periodic Table of Atheists and Antitheists. While I admire its artistry, I deplore its lack of accuracy. At least three of the people listed as atheists or anti-theists were nothing of the sort: Albert Einstein, Mark Twain and (in his final days) Jean-Paul Sartre. I realize that the last name will shock many readers. I’ll say more about Sartre anon.

I’m a great admirer of Einstein (who isn’t?) and a fan of Mark Twain, whose house I visited in December 1994. And I thoroughly enjoyed reading Sartre’s Les Mains Sales (Dirty Hands) in high school. When he wrote that play in 1948, Sartre was a militant atheist, but as we’ll see, Sartre’s views changed in his final years. These three authors I treasure, so I say to the atheists: you can’t have them!

There are three more people on Ungodly News’ periodic table who, in the interests of historical accuracy, I have to say don’t belong there either: Charles Darwin, Thomas Henry Huxley and Bill Gates. All three are (or were) agnostics, not atheists, and as I’ll argue below, while these thinkers all reject the claims of revealed religion, none of them deserves to be called an anti-theist. It is an undeniable historical fact, however, that the ideas disseminated by Darwin and Huxley have caused many people to lose their faith in God.

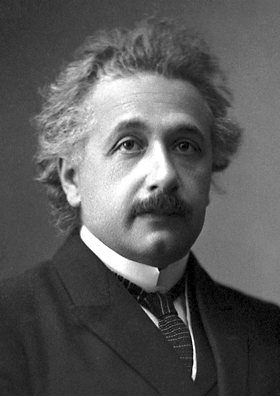

Atheists love to claim Albert Einstein as one of their own, but he was nothing of the sort.

[This post will remain at the top of the page until 6:00 am EST tomorrow, June 28. For reader convenience, other coverage continues below. – UD News]

It is well-known that Albert Einstein rejected belief in an afterlife, and did not believe in a personal God who answered prayers. Nevertheless, he did believe in a Mind manifesting itself in Nature. That was his God. In an interview published in 1930 in G. S. Viereck’s book Glimpses of the Great, Einstein remarked:

I’m absolutely not an atheist. I don’t think I can call myself a pantheist. The problem involved is too vast for our limited minds. We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows someone must have written those books. It does not know how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangement of the books but doesn’t know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God. We see the universe marvelously arranged and obeying certain laws but only dimly understand these laws. Our limited minds grasp the mysterious force that moves the constellations. I am fascinated by Spinoza’s pantheism, but admire even more his contribution to modern thought because he is the first philosopher to deal with the soul and body as one, and not two separate things. (Frankenberry, Nancy K. 2009. The Faith of Scientists: In Their Own Words. Princeton University Press. p. 153.)

In 1929, Albert Einstein told Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein: “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.” (Isaacson, Walter, Einstein: His Life and Universe, pp. 388-389, Simon and Schuster, 2008.)

According to Hubertus, Prince of Lowenstein-Wertheim-Freudenberg, Einstein said, “In view of such harmony in the cosmos which I, with my limited human mind, am able to recognize, there are yet people who say there is no God. But what really makes me angry is that they quote me for the support of such views.” (Quoted by Ronald W. Clark, Einstein: The Life and Times, New York: World Publishing Company, 1971, p. 425.)

For an overview of Einstein’s religious views, I’d recommend this article in Wikipedia.

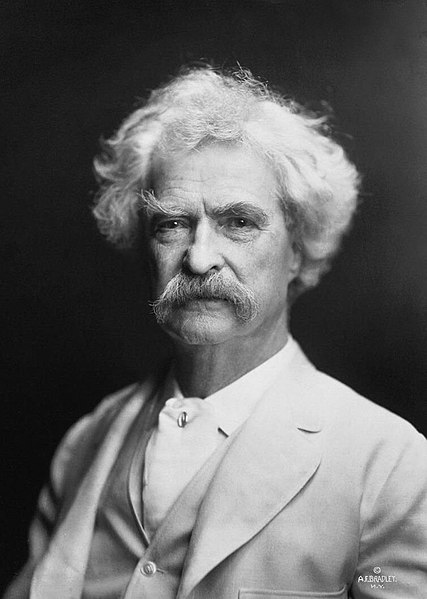

Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) certainly wasn’t an atheist either. As he wrote:

To trust the God of the Bible is to trust an irascible, vindictive, fierce and ever fickle and changeful master; to trust the true God is to trust a Being who has uttered no promises, but whose beneficent, exact, and changeless ordering of the machinery of His colossal universe is proof that He is at least steadfast to His purposes; whose unwritten laws, so far as the affect man, being equal and impartial, show that he is just and fair; these things, taken together, suggest that if he shall ordain us to live hereafter, he will be steadfast, just and fair toward us. We shall not need to require anything more.

— Mark Twain, from Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain, a Biography (1912), quoted from Barbara Schmidt, ed, “Mark Twain Quotations, Newspaper Collections, & Related Resources”.

Was Twain anti-religious? Certainly. But anti-theist? No. Twain loved to make fun of God, but he also believed God was big enough not to be troubled by such mockery:

Blasphemy? No, it is not blasphemy. If God is as vast as that, he is above blasphemy; if He is as little as that, He is beneath it. (Ibid.)

Twain’s views on the afterlife, like his views on Providence, varied throughout his lifetime, but his daughter Clara said of him: “Sometimes he believed death ended everything, but most of the time he felt sure of a life beyond.” (Phipps, William E., Mark Twain’s Religion, p. 304, 2003 Mercer Univ. Press.)

What about Jean-Paul Sartre? According to his personal secretary Benny Levy (a.k.a. Pierre Victor), an ex-Maoist who became an Orthodox Jew in the late 1970s, Sartre had a drastic change of mind about the existence of God and started gravitating toward Messianic Judaism, in the years before his death. This is Sartre’s before-death profession, according to Pierre Victor: “I do not feel that I am the product of chance, a speck of dust in the universe, but someone who was expected, prepared, prefigured. In short, a being whom only a Creator could put here; and this idea of a creating hand refers to God.”

What was Simone de Beauvoir’s reaction, you may be wondering?

“His mistress, Simone de Beauvoir, behaved like a bereaved widow during the funeral. Then she published La ceremonie des adieux in which she turned vicious, attacking Sartre. He resisted Victor’s seduction, she recounts, then he yielded. ‘How should one explain this senile act of a turncoat?’, she asks stupidly. And she adds: ‘All my friends, all the Sartreans, and the editorial team of Les Temps Modernes supported me in my consternation.’

Mme. de Beauvoir’s consternation v. Sartre’s conversion. The balance is infinitely heavier on the side of the blind, yet seeing, old man.”

(National Review, NY, 11 June 1982, p. 677, article by Thomas Molnar, Professor of French and World Literature at Brooklyn College; see also McDowell, Josh and Don Stewart, eds. 1990. Concise Guide to Today’s Religions. Amersham-on-the-Hill, Bucks, England: Scripture Press, p. 477.)

The transformation in Sartre’s political and religious views near the end of his life is revealed in a book of conversations between Sartre and his assistant Benny Levy, conducted shortly before his death, Hope Now: The 1980 Interviews (University of Chicago Press, 1996). The publisher of the book described the changes as follows:

“In March of 1980, just a month before Sartre’s death, Le Nouvel Observateur published a series of interviews, the last ever given, between the blind and debilitated philosopher and his young assistant, Benny Levy.

They seemed to portray a Sartre who had abandoned his leftist convictions and rejected his most intimate friends, including Simone de Beauvoir. This man had cast aside his own fundamental beliefs in the primacy of individual consciousness, the inevitability of violence, and Marxism, embracing instead a messianic Judaism. (…)

Shortly before his death, Sartre confirmed the authenticity of the interviews and their puzzling content. Over the past fifteen years, it has become the task of Sartre scholars to unravel and understand them. Presented in this fresh, meticulous translation, the interviews are framed by two provocative essays by Benny Levy himself, accompanied by a comprehensive introduction from noted Sartre authority Ronald Aronson.

This absorbing volume at last contextualizes and elucidates the final thoughts of a brilliant and influential mind.”

(See Hope Now: The 1980 Interviews, Jean-Paul Sartre and Benny Levy (ed.); translated by Adrian Van den Hoven, with an introduction by Ronald Aronson, University of Chicago Press, 1996).

Curious readers can find out more by having a look at Part II (section 34) of Tihomir Dimitrov’s online book, 50 Nobel Laureates and other great scientists who believed in God.

So, was Jean-Paul Sartre an atheist, or even an anti-theist, at the end of his life? Evidently not.

There are three more names which don’t belong in Ungodly News’ Periodic Table of Atheists and Antitheists:

(1) Charles Darwin. Although his book The Origin of Species undoubtedly caused many readers to lose their religious faith, Darwin himself was not an atheist. As he wrote in a letter to John Fordyce, an author of several works on skepticism, on 7 May 1879: “It seems to me absurd to doubt that a man may be an ardent Theist & an evolutionist… In my most extreme fluctuations I have never been an atheist in the sense of denying the existence of a God. — I think that generally (and more and more so as I grow older), but not always, — that an agnostic would be the most correct description of my state of mind.”

Darwin remained close friends with the vicar of Downe, John Innes, and continued to play a leading part in the parish work of the church. (See this article for more information.)

Atheist? Obviously not. Anti-theist? I think not. The man was an agnostic.

(2) Thomas Henry Huxley. Huxley was an agnostic (a term he coined himself in 1869), rather than an atheist. Here is his account of how he coined the term:

When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist; a materialist or an idealist; Christian or a freethinker; I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer; until, at last, I came to the conclusion that I had neither art nor part with any of these denominations, except the last. The one thing in which most of these good people were agreed was the one thing in which I differed from them. They were quite sure they had attained a certain “gnosis,”–had, more or less successfully, solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble.

So I took thought, and invented what I conceived to be the appropriate title of “agnostic.” It came into my head as suggestively antithetic to the “gnostic” of Church history, who professed to know so much about the very things of which I was ignorant. To my great satisfaction the term took. (Huxley, Thomas. Collected Essays, pp. 237–239. ISBN 1-85506-922-9.)

In a letter of September 23, 1860, to Charles Kingsley, Huxley touched on the subject of immortality:

I neither affirm nor deny the immortality of man. I see no reason for believing it, but, on the other hand, I have no means of disproving it.

Pray understand that I have no a priori objections to the doctrine. No man who has to deal daily and hourly with nature can trouble himself about a priori difficulties. Give me such evidence as would justify me in believing in anything else, and I will believe that. Why should I not? It is not half so wonderful as the conservation of force or the indestructibility of matter. Whoso clearly appreciates all that is implied in the falling of a stone can have no difficulty about any doctrine simply on account of its marvellousness.

Or as he put it in another letter to Kingsley, dated May 5, 1863, when discussing the immortality of the soul and the belief in future rewards and punishments:

Give me a scintilla of evidence, and I am ready to jump at them.

According to his Wikipedia biography, Huxley even supported the reading of an edited version of the Bible (shorn of “shortcomings and errors”) in schools. He believed that the Bible’s significant moral teachings and superb use of language were of continuing relevance to English life. As he put it:

“I do not advocate burning your ship to get rid of the cockroaches.”

(THH 1873. Critiques and Addresses, p. 90.)

I submit that while Huxley was certainly a fierce opponent of organized religion, he can hardly be called an anti-theist.

(3) Bill Gates. According to the very link cited by Ungodly News, Bill Gates is an agnostic, not an atheist. In his own words:

In terms of doing things I take a fairly scientific approach to why things happen and how they happen. I don’t know if there’s a god or not, but I think religious principles are quite valid.

Does that sound like the utterance of an “anti-theist” to you? No? I didn’t think so either.

Albert Einstein, Mark Twain, Jean-Paul Sartre, Charles Darwin, Thomas Henry Huxley, Bill Gates – that’s six mistakes altogether. That doesn’t sound like a very accurate periodic table to me. I’d say Ungodly News has got some ‘splainin’ to do!