UD’s resident journalist, Mrs Denise O’Leary, notes on how Mr Michael Shermer of Skeptic Magazine and Scientific American (etc.) has written on his new book, The Believing Brain: Why Science Is the Only Way Out of Belief-Dependent Realism:

. . . skepticism is a sine qua non of science, the only escape we have from the belief-dependent realism trap created by our believing brains.

While critical awareness — as opposed to selective hyperskepticism — is indeed important for serious thought in science and other areas of life, Mr Shermer hereby reveals an unfortunate ignorance of basic epistemology, the logic of warrant and the way that faith and reason are inextricably intertwined in the roots of our worldviews.

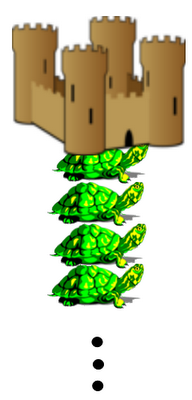

To put it simply, he has a “turtles all the way down” problem:

The image of course comes from the old story of the lady who told the scientist that the world rests on the back of a turtle. The scientist challenged her, and where does that turtle stand? On another one. And that one? “It’s turtles all the way down . . . ”

The same problem holds for warranting a given claim. As I noted in a comment in Mrs O’Leary’s thread (which Mr Arrington suggested be promoted to a full post):

Take any given claim of consequence A. Why accept it?

It has grounds of some sort B.

Why accept B?

C.

And so forth.

You will then have the choice of:

(i) infinite regress [“turtles all the way down . . . “],

(ii) a circle [“turtles in a loop . . . “] or

(iii) stopping at some set of first plausibles F that are accepted as that, plausible without further demonstration. [“The last turtle stands on something, hopefully something solid”].

The first two are absurd and fallacious in turn.

Since many such sets F are possible, the matter now turns to comparative difficulties on factual adequacy, coherence and explanatory power across live options F1, F2, F3 etc.

Have a look here on.

But, every such set F, is a Faith-point. Faith and reason are inextricably intertwined in the roots of our worldviews.

This brings us to the real issue: not whether we live by faith — we must — but in what do we put our trust, why.

That is, we seek to have a reasonable faith.

We are thus forced to stop at some set of first plausibles or other — that is, a “faith-point” (yes, we ALL must live by some faith or another, given our finitude and fallibility) — and then compare alternatives and see which is least difficult. (At this level, all sets of alternative first plausibles bristle with difficulties. Indeed, the fundamental, generic method of philosophy is therefore that of comparative difficulties.)

John Locke aptly summed up our dilemma in section 5 of his introduction to his famous essay on human understanding:

Men have reason to be well satisfied with what God hath thought fit for them, since he hath given them (as St. Peter says [NB: i.e. 2 Pet 1:2 – 4]) pana pros zoen kaieusebeian, whatsoever is necessary for the conveniences of life and information of virtue; and has put within the reach of their discovery, the comfortable provision for this life, and the way that leads to a better. How short soever their knowledge may come of an universal or perfect comprehension of whatsoever is, it yet secures their great concernments [Prov 1: 1 – 7], that they have light enough to lead them to the knowledge of their Maker, and the sight of their own duties [cf Rom 1 – 2 & 13, Ac 17, Jn 3:19 – 21, Eph 4:17 – 24, Isaiah 5:18 & 20 – 21, Jer. 2:13, Titus 2:11 – 14 etc, etc]. Men may find matter sufficient to busy their heads, and employ their hands with variety, delight, and satisfaction, if they will not boldly quarrel with their own constitution, and throw away the blessings their hands are filled with, because they are not big enough to grasp everything . . . It will be no excuse to an idle and untoward servant [Matt 24:42 – 51], who would not attend his business by candle light, to plead that he had not broad sunshine. The Candle that is set up in us [Prov 20:27] shines bright enough for all our purposes . . . If we will disbelieve everything, because we cannot certainly know all things, we shall do muchwhat as wisely as he who would not use his legs, but sit still and perish, because he had no wings to fly. [Emphases added. Text references also added, to document the sources of Locke’s biblical allusions and citations.]

So, we must make the best of the candle-light we have. At worldview choice level, a good way to do that is to look at three major comparative difficulties tests:

(1) factual adequacy relative to what we credibly know about the world and ourselves,

(2) coherence, by which the pieces of our worldview must fit together logically and work together harmoniously,

(3) explanatory relevance and simplicity: our view needs to explain reality (including our experience of ourselves in our common world) elegantly, simply and powerfully, being neither simplistic nor a patchwork where we are forever adding after-the-fact patches to fix leak after leak.

Two key components of this process of comparative difficulties in pursuit of a worldview that is a reasonable faith, are: (i) first principles of right reason, and (ii) warranted, credible truths.

And, when it comes to matters of fact, our challenge is aptly summed up by founder of the modern theory of evidence, Simon Greenleaf, in his famouse treatise on Evidence:

The word Evidence, in legal acceptation, includes all the means by which any alleged matter of fact, the truth of which is submitted to investigation, is established or disproved . . . .

None but mathematical truth is susceptible of that high degree of evidence, called demonstration, which excludes all possibility of error [Greenleaf was almost a century before Godel] , and which, therefore, may reasonably be required in support of every mathematical deduction. Matters of fact are proved by moral evidence alone ; by which is meant, not only that kind of evidence which is employed on subjects connected with moral conduct, but all the evidence which is not obtained either from intuition, or from demonstration.

In the ordinary affairs of life, we do not require demonstrative evidence, because it is not consistent with the nature of the subject, and to insist upon it would be unreasonable and absurd. The most that can be affirmed of such things, is, that there is no reasonable doubt concerning them. The true question, therefore, in trials of fact, is not whether it is possible that the testimony may be false, but, whether there is sufficient probability of its truth; that is, whether the facts are shown by competent and satisfactory evidence. Things established by competent and satisfactory evidence are said to he proved . . . .

By competent evidence, is meant that which the very-nature of the thing to be proved requires, as the fit and appropriate proof in the particular case, such as the production of a writing, where its contents are the subject of inquiry. By satisfactory evidence, which is sometimes called sufficient evidence, is intended that amount of proof, which ordinarily satisfies an unprejudiced mind, beyond reasonable doubt. The circumstances which will amount to this degree of proof can never be previously defined; the only legal test of which they are susceptible, is their sufficiency to satisfy the mind and conscience of a common man ; and so to convince him, that he would venture to act upon that conviction, in matters of the highest joncern and importance to his own interest . . . .

Even of mathematical truths, [Gambler, in The Study of Moral Evidence] justly remarks, that, though capable of demonstration, they are admitted by most men solely on the moral evidence of general notoriety. For most men are neither able themselves to understand mathematical demonstrations, nor have they, ordinarily, for their truth, the testimony of those who do understand them; but finding them generally believed in the world, they also believe them. Their belief is afterwards confirmed by experience; for whenever there is occasion to apply them, they are found to lead to just conclusions. [A Treatise on the Law of Evidence, 11th edn, 1868 [?], vol 1 Ch 1 , pp. 45 – 46.]

So the key challenge is that one must have a reasonable and responsible consistency in standards of warrant on important matters of fact or matters rooted in facts.

We thus see the standard of reasonable and consistent, albeit provisional warrant that appears in all sorts of serious contexts such as the courtroom, history, science [especially origins sciences], and many matters of affairs.

Mr Shermer needs to do some fairly serious rethinking on the relationship between faith and reason. END