This morning, on opening up my email acount, I encountered a comment from one of UD’s critics, LT, in which he pointed to this post at his blog, which begins:

I am starting to come around to the way of thinking espoused by Kairosfocus [–>NB: I can claim no originality on this], who has argued that we must build our worldviews from first principles and compare how different worldviews address various difficulties. The comparative aspect is important. If we have proper grasp of a fact–as in, for instance, an apple falling to earth–we should be able to reconcile the fact and the worldview. A worldview in which apples do not fall to earth (yes, I understand that “fall” is a relative term) is less compatible with the facts than other views in which falling makes sense. The cumulative effect of comparing different worldviews against many–maybe dozens–of difficulties is to give one confidence in the smallest possible set of views. Some views may be very warranted. Maybe only one view is most warranted . . .

In short the core concept of worldviews analysis by comparative difficulties linked to tracing such views to their first plausibles is being accepted, and with it the general framework of first principles of right reason.

(I note on quantum issues that quantum objects –“wavicles” — are quite distinct from more familiar entities (which the quantum objects approach asymptotically as systems get larger) and so the way in which first principles of right reason will apply is different, but they do in fact apply as can be seen from the way physicists use them in how experimental results are interpreted and in how calculations are scratched out on the proverbial chalk boards. Of more significance is the modern view of the empty set and quantifiers, with existential import being reserved for the existential quantifier. That means that “ALL A is P” and “NO A is P” may both refer to nothing. Quite subtle consequences stem from that, which we reserve for more advanced stages of reasoning. Let us start with sets that are generally not empty, save where the definition of the set directly or by implication makes them so.)

Preliminaries aside, the key point now being raised by LT is a question about the law of cause and effect and its relationship to other first principles:

Before I ask Kairosfocus a question about principle [d] [i.e.: “if something has a beginning or may cease from being — i.e. it is contingent — it has a cause.” ], the principle of cause and effect, I want to observe that [d] bears no direct relationship to principles [a] through [c]. One cannot get from the first three to the fourth, in other words. Principle [c], for instance, contains nothing in it (as formulated) to imply that thing A has a history. Although principles [a] – [c] define a relationship between thing A and the rest of the universe, these principles mainly address the relationship of thing A with itself.

I also observe that the phrasing of [d] is different than [a] -[c], and this is where my question comes in:

- The “if” is a conditional; it introduces a test condition.

- The test concerns whether something has a beginning or not, and whether something may cease from being or not.

- A workable test condition needs to be able to verify all results of the test:

- Thing A has a beginning.

- Thing A may cease from being.

- Thing A does not have a beginning.

- Thing A may not cease from being.

- If we cannot verify some results–that is, if we have no way to confirm results–then our test is flawed and needs improvement. [–>WP is messing up this list from blogger badly]

My question to Kairosfocus, then is simply this: What are the tests we can use to determine whether a thing does not have a beginning or may not cease from being?

Principle d of course does not simply trace to the LOI, LNC and LEM.

(I should also note that the remarks about testing come very close to the infamous and spectacularly failed verification principle of the logical positivists. Is it subject to its own test, and is the answer subject to its own tests, etc? Empirical testing is not he only mark of truth, hence the significance of coherence and explanatory power as worldviews tests.)

Before we get to the principle of cause and effect, there is a further principle that in the discussion LT has cited is mentioned in a by the way fashion, but which in the expanded “six principles” format, is expanded as a distinct numbered point, no 5, just after giving a definition of truth; namely the principle of sufficient reason, here cited from Schopenhauer.

Clipping my worldviews foundations discussion:

We should also note that a fourth key law of sound thought is the principle of sufficient reason , which enfolds the principle of cause and effect. Schopenhauer in his Manuscript Remains, Vol. 4, notes that: “Of everything that is, it can be found why it is.”

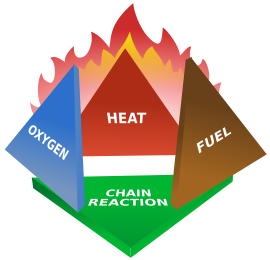

The fire tetrahedron (an extension of the classic fire triangle) is a helpful case to study briefly:

For a fire to begin or to continue, we need (1) fuel, (2) heat, (3) an oxidiser [usually oxygen] and (4) an un- interfered- with heat-generating chain reaction mechanism. (For, Halon fire extinguishers work by breaking up the chain reaction.) Each of the four factors is necessary for, and the set of four are jointly sufficient to begin and sustain a fire. We thus see four contributory factors, each of which is necessary [knock it out and you block or kill the fire], and together they are sufficient for the fire.

We thus see the principle of cause and effect. That is,

[d] if something has a beginning or may cease from being — i.e. it is contingent — it has a cause.

Common-sense rationality, decision-making and science alike are founded on this principle of right reason: if an event happens, why — and, how? If something begins or ceases to exist, why and how? If something is sustained in existence, what factors contribute to, promote or constrain that effect or process, how? The answers to these questions are causes.

Without the reality behind the concept of cause the very idea of laws of nature would make no sense: events would happen anywhere, anytime, with no intelligible reason or constraint.

As a direct result, neither rationality nor responsibility would be possible; all would be a confused, unintelligible, unpredictable, uncontrollable chaos. Also, since it often comes up, yes: a necessary causal factor is a causal factor — if there is no fuel, the car cannot go because there is no energy source for the engine. Similarly, without an unstable nucleus or particle, there can be no radioactive decay and without a photon of sufficient energy, there can be no photo-electric emission of electrons: that is, contrary to a common error, quantum mechanical events or effects, strictly speaking, are not cause-less.

So the secret to understanding cause is to understand the issue of a necessary causal factor, the “switch” that must be on for something to begin or continue to be.

Of course with several such switches in a chain, all must be on or the effect will be disabled. And, we may have the possibility of parallel chains, so that if one chain is blocked but another is open, the effect may still happen.

(This key example comes from digital electronics and the study of logic gates. The enabling/disabling gate is a very important tool in the system designer’s chest. My favourite case being to use a JK flipflop as a latching switch, by feeding back from the output so that once Q is triggered high, it locks the circuit in a storage state until it is externally reset. Which also brings up the possibility of feedback loops in causal chains, with lags around the loop imposing memory. This is in fact the basis of memory devices and cybernetic control. Looping is also vital in software design. It is also a source of all sorts of instability and breakdown.)

Once we see the significance of the necessary causal factor, we can now identify things that are not contingent: they have no necessary causal factors. So, we can go look for “switches” or for switch-prompted behaviour, i.e. the beginning/ending, or the possibility of ending, or of course obvious dependence on a feeding factor.

That fuel line to the car engine is a dead giveaway.

So is the existence of metabolism joined to digital code based self replicating capacity in the living cell.

So is the credible conclusion that our observed cosmos began in a big bang some 13.7 BYA. Any physical entity in our observed cosmos is therefore contingent, as is the observed cosmos as a whole.

And, note that key term: observed.

Similarly, any entity that is dependent for its ability to function on the particular co-ordinated physical arrangement of parts is contingent, as if the parts are moved around or separated such a composite entity will cease to be or will break down.

Auto parts shops have a surprisingly deep philosophical significance, never mind that chilling, long low whistle from under your car when the mechanic is looking at it.

By way of contrast, the truth asserted in the structured set of symbols: 2 + 3 = 5 always was, will always be, cannot be denied on pain of absurdity, etc. It cannot break down and does not need to be repaired.

It is a necessary being.

(We need not trouble ourselves for the moment on the 2400 year old debate on whether such may only be instantiated in physical entities. Suffice to say that such mathematical or more broadly propositional truths capture assertions about reality that may or may not be true, but if true can have very powerful implications. Thence, the “unreasonable” effectiveness of mathematics in science: If X then Y, holds, once X is found.)

If something is so or exists, the principle of sufficient reason now asks: why, and implies that (in principle of course) it can be answered in some sensible way.

This leads to what is at first a strange seeming conclusion: a world of contingent beings that is itself credibly contingent cries out for a necessary being as its explanation. That is, a being that is the terminus of cause, and which has a similar character to the truth asserted in 2 + 3 = 5.

Formerly, that necessary being was thought to be the observed cosmos as a whole, as say the Steady State cosmological model and the underlying earlier “scientific” view of the cosmos as a going entity that as far as was then known always was there suggested. But that model had a fatal collision with observed evidence and so we are left with a model with a beginning for our observed cosmos.

BTW, the ONLY observed universe.

We now cross the border into philosophy, not science . . .

Multiverse speculations and ideas of quantum fluctuations etc with cosmi bubbling up from an underlying substrate are in effect updates to the steady state view. That is, the real issue is not so much whether there is an ultimate, but what it — or, s/he — is.

Cosmological design thinkers, by contrast with the sort of extended steady state philosophical speculations just mentioned, argue that the observed cosmos is so carefully organised and arranged to foster C-chemistry, aqueous medium cell based life that the best explanation is that the cosmos is made by a cosmic architect. (Cf here and here on in context for 101 level discussions of why, and note the onward links for more.)

So, the key issue is in fact the principle of sufficient reason, which is almost misleadingly simple given how powerful it is.

Indeed, the principle of causality is deduced from it, for the case where an entity evidently — on grounds that are particular to the individual case in view, but which we can usually fairly easily see — has at least one necessary factor that if present enables its beginning or sustains it in being. END