One of the recent brouhahas in the rising “silly season” of the 2012 US election cycle, is how certain ID-friendly candidates such as Mrs Michelle Bachmann, are allegedly Christo-fascist “Dominionists” influenced by that nefarious “Dominionist,” the late theologian, Francis Schaeffer.

All of this is in a context where, in the recent Aug 17, 2011 B4U-ACT pro pedophilia conference, we heard academic advocates asserting that:

Our society should “maximize individual liberty. We have a highly moralistic society that is not consistent with liberty.” [Cf.onward UD post here.]

Of course, this patently and potentially destructively confuses license for true liberty, as can be easily seen by comparing the classic definitions in the Webster’s 1828 Dictionary:

LIB’ERTY, n. [L. libertas, from liber, free.] . . .

3. Civil liberty, is the liberty of men in a state of society, or natural liberty [i.e. sense 1: “. . . the power of acting as one thinks fit, without any restraint or control, except from the laws of nature.”], so far only abridged and restrained, as is necessary and expedient for the safety and interest of the society, state or nation. A restraint of natural liberty, not necessary or expedient for the public, is tyranny or oppression. civil liberty is an exemption from the arbitrary will of others, which exemption is secured by established laws, which restrain every man from injuring or controlling another. Hence the restraints of law are essential to civil liberty.The liberty of one depends not so much on the removal of all restraint from him, as on the due restraint upon the liberty of others. In this sentence, the latter word liberty denotes natural liberty.

LI’CENSE, n. [L. licentia, from liceo, to be permitted.] . . .

2. Excess of liberty; exorbitant freedom; freedom abused, or used in contempt of law or decorum.License they mean, when they cry liberty.

It is worth pausing to see and to note how, again and again, we can see how insightful George Orwell’s 1984 was: the willful corruption of language is the first step to shackling men’s minds to a new tyranny.

In addition, we must recognise the close link between genuine liberty, duties and rights, for without duties of neighbourliness in the circle of the civil peace of justice, there can be no basis for rights.

Likewise, when we hear silly smear-words like “Christo-fascist” being tossed around, it is a helpful first cross check to notice that the most notorious case in point of Fascism, was called National SOCIALISM. (Without endorsing all that is said in the links, take a quick look here and here for an eye-opener.)

Having cleared the air of some poisonous and polarising smoke, we can now see clearly enough to understand Francis Schaeffer a bit better, as an example of a Christian thinker responding responsibly to the key worldview trends and issues of our civilisation, at a serious level.

(Not least, we should note the pioneering significance of Schaeffer in this regard, as the man who almost single-handedly taught evangelical Christians in the generation of the 1950’s – 80’s, to think in worldview terms, and to engage the cultural and spiritual implications of worldviews. And as a pivotal pioneer who had vast impact within the church and significant impact on many lost souls and the wider Western Culture at large in the era of despair in the aftermath of the shockingly dark age revealed by the horrors of two World Wars and the looming shadow of global nuclear war and/or Communist conquest, we should not disown him or dismiss his heritage because of whatever inevitable flaws we will find there. For, we are all finite, fallible, morally falling/struggling, and more often ill-willed than we like to admit.)

Thanks to some sterling contributions by longtime UD commenter and contributor StephenB, we may now adapt Steve Sawyer’s Amazon reader review [as adjusted to clarify and correct the analysis] as a pretty good start point for a renewed, critically aware appreciation:

Schaeffer sees the true beginning of the humanistic Renaissance in the work of Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). [Here, we must correct:] Aquinas’

dualisticGrace/Nature scheme [for analysing ways different truths are warranted as knowledge] was useful in many ways, but its critical flaw was in failing to [fully draw out and underscore the impacts of]recognizeman’s fallen intellect along with his fallen will [in engaging the issue of natural theology in certain key much- referred- to texts, where natural theology in light of Rom 1:18 – 24 & 28 – 32, Eph 4:17 – 24, 2 Cor 10:4 – 5 and Ac 17:16 – 34 is inescapably an exploration of what we can learn and warrant about God from observing our common world, and our hearts and minds within]. [While] Aquinas [From Summa Theol I Q 85, Art 3 clearly] saw man’s intellect asessentially undamaged[wounded and impaired] by the Fall [when he set up the project of natural theology in Summa Theol I, Question 1, he did not there and then fully address the emphatic concerns Paul had on how a fallen and willfully rebellious, warped mind can find itself inexcusably caught up in a stubborn rejection of the evidence from our world and from our inner life that points strongly to God; willfully locking God out from the sphere of knowledge and thus triggering chaos in one’s life and community]. This [understandable — Aquinas lived in a place and time in which the existence of God seemed all but self evident — want of full emphasis] had the unfortunate [and plainly unintended] consequence of setting up [a way for others in future generations to improperly treat] man’s intellect as autonomous and independent.Aquinas [had] adapted parts of Greek [and Islamic] philosophy to Christianity [and also drew on Paul’s note in Rom 1:19 – 20 that there is enough evidence in the world to strongly point us to God], [however, he did not “there and then” sufficiently emphasise what follows in vv. 21 – 32, on how we can end up suppressing that testimony, setting up systems of thought and ways of life that suppress that evident truth.]

[In looking back, we can see that] perhaps most importantly (and with the most negative consequences) [he then threw the weight of his focus on how an exploration of what would later be called natural theology, draws a distinction between what is common to man: natural reason, and what must be drawn from revelation by grace through faith. Commendably, he expressed his strong confidence in the truth we can know from revelation and even stated that truths of grace should correct our errors in using our natural reason.] [However, what in the end counted in the hands of later men of a more skeptical bent,] was his emphasis on the [difference between what can be learned naturally and what must be learned from revelation, which invited others to take up a fully] dualistic view of man and world as represented by the Grace/Nature split. As Schaeffer stresses, the main danger of a dualistic scheme is that, eventually, the lower sphere “eats up” the upper sphere. Another way to say the same thing is, once the lower sphere is given “autonomy,” it tends to deny the existence or importance of whatever is in the upper sphere in support of its own autonomy.

Schaeffer explains how the Grace/Nature dualism eventually became the Freedom/Nature, then the Faith/Rationality split. He introduces his interesting idea of the Line of Despair, which began in philosophy with Hegelian relativism [and with Kant’s similar dichotomising of the world of experience from the inner life of the conscious mind joined to his dismissal of the concept of self-evident truth] . Kierkegaard was the first major figure after this line. The line of despair is the point in history at which philosophers (and others) gave up on the age-old hope of a unified (i.e. not dualistic) answer for knowledge and life.

This new despairing way of thinking spread in 3 ways; geographically, from Germany outward to Europe, England and finally much later to America. Then by classes, from the intellectuals to the workers via the mass media (the middle classes were largely unaffected and remained a product of the Reformation, thankfully for stability, but this is why the middle class didn’t understand its own children). Finally, it spread by disciplines; philosophy (Hegel), art (post-impressionists), music (Debussy), general culture (early T S Eliot)…then lastly theology (Barth).

Once this way of thinking set in, Schaeffer explains the need for “the leap,” promoted by both secular and religious existentialists. On the secular side, Sartre located this leap in “authenticating oneself by an act of the will,” Jaspers spoke of the need for the “final experience” and Heidegger talked of ‘angst,’ the vague sense of dread resulting from the separation of hope from the rational ‘downstairs.’ On the religious side, we have Barth preaching the lack of any interchange between the upper and lower spheres, using the higher criticism to debunk parts of the Bible, but saying we should believe it anyway. “‘Religious truth’ is separated from the historical truth of the Scriptures. Thus there is no place for reason and no point of verification. This constitutes the leap in religious terms. Aquinas opened the door to an independent man downstairs, a natural theology and a philosophy which were both autonomous from the Scriptures. This has led, in secular thinking, to the necessity of finally placing all hope in a non-rational upstairs” (p. 53, thus the book’s title). This is in contrast to the biblical and Reformation message that even though man is fallen, he can and must search the scriptures to find the verifiable truth. Schaeffer devotes a lot of space in his book to illustrating the many ways modern men have taken this “leap,” assuming there is no rational way upstairs.

Schaeffer ends with a call to reject dualism and return to the reformation view of the scriptures, which is that God has spoken truth not only about Himself, but about the cosmos and history (p. 83). In order to do this, man must give up rationalism (i.e. autonomous reason), but by doing so he can retrieve rationality. “Modern man longs for a different answer than the answer of his damnation. He did not accept the Line of Despair and the dichotomy because he wanted to. He accepted it because, on the basis of the natural development of his rationalistic presuppositions, he had to. He may talk bravely at times, but in the end it is despair” (p. 82). No area of life can be autonomous of what God has said, since this will inevitably lead to the destruction of all value (including God, freedom and man). By placing all human activity within the framework of what God has told us, “it gives us the form inside which, being finite, freedom is possible” (p. 84).

God created man as significant, and he still is, even in his fallen and lost state. He is not a machine, plant or animal. He continues to bear the marks of “mannishness” (p. 89): love, rationality, longing for significance, fear of non-being, and so on. He will never be nothing.

The author emphasizes the existence of certain unchanging facts, which are true regardless of the shifting tides of man’s thoughts. He challenges Christians to understand these tides and speak the unchanging truth in a way that can be understood in the midst of them.

We may capture this extended, somewhat corrected Schaefferian vision in two diagrams based on his famous Grace/Nature Dichotomy and Line of Despair diagrams in Escape from Reason.

In the first diagram, we see how once the unity of grace and nature is compromised, nature tends to become autonomous and “eats up” grace. As Schaeffer came to accept by the time of his 1982 revised edition of Escape from Reason, the actual dichotomising occurred under those who succeeded Aquinas, as the project of natural theology took up a life of its own and natural reasoning became increasingly autonomous and eventually increasingly skeptical, leading to a fundamental and in the end irreconcilable disjointedness in the worldview of Western Man:

In the second diagram, we look at the timeline that follows, as the project of natural theology was challenged increasingly by autonomous rationalising then eventually outright naturalistic skepticism; of course culminating in Darwinism; which is seen by the dominant part intellectual elites as making the apparent design of life credibly only apparent — though the problem of imposed a priori Lewontinian materialism significantly undercuts that case for those who understand that issue.

This also provides a capital case in point of how a priori, censoring worldview level commitments block people from receiving the actual force of evidence that may be presented by those involved in a natural theology exercise. Let us therefore cite the key passage in Lewontin’s 1997 NYRB article, Billions and Billions of Demons,” as just linked:

. . . To Sagan, as to all but a few other scientists, it is self-evident [[actually, science and its knowledge claims are plainly not immediately and necessarily true on pain of absurdity, to one who understands them; this is another logical error, begging the question , confused for real self-evidence; whereby a claim shows itself not just true but true on pain of patent absurdity if one tries to deny it . . ] that the practices of science provide the surest method of putting us in contact with physical reality, and that, in contrast, the demon-haunted world rests on a set of beliefs and behaviors that fail every reasonable test [[i.e. an assertion that tellingly reveals a hostile mindset, not a warranted claim] . . . .

No wonder, Philip Johnson was led to retort as follows, some months later in a First Things article:

In short, we can see through a by now familiar case, just how much the root problem is not the strength of evidence or the quality of logic as such, but the a priori imposition of ideological materialism on origins science. Worse, Lewontin and others apparently do not realise that the claim, assumption or inference that “science [[is] the only begetter of truth” is not a claim within science but instead a philosophical claim about how we get warranted, credibly true belief, i.e. knowledge. So, they have contradicted themselves: appealing to non-scientific knowledge claims to try to deny the possibility of knowledge beyond science!

In short, professing themselves wise, we have here instead a stumbling into patent but unrecognised absurdity.

That is why Schaeffer’s focus on the historical and ideas roots of worldviews and on critically analysing the incoherence of modern secular humanist and/or neo-pagan views is so important.

In this process of course a key point to note, of course, is that Schaeffer was demonstrably incorrect to infer that Aquinas thought that the mind was not impaired by the primordial Fall. But, it is equally true that in certain key texts in Aquinas’ voluminous corpus of work — texts that in succeeding generations of discussion and debate over natural theology tended to take on a life of their own, directly and indirectly — Aquinas’ discussion of the project of natural theology did not “there and then” emphasise the issue of how even compelling evidence will be blunted in its effects by resistance to unwelcome conclusions, backed up by worldview level commitments that can make even patent truth seem absurd or simply wrong. We just saw how decisive that can be, with Lewontinian a priori materialism. And, ironically, the issue of willful and intellectually irresponsible blindness to evident reason actually the central emphasis in Paul’s discussion of the same natural theology themes that Aquinas based his arguments on.

On fair comment, this subtle error of emphasis opened the door to a pattern of development across time, which demands an adequate worldview level response, hence the continued relevance of Schaeffer’s work:

Iconoclastic former Bultmannian and evangelical theologian Eta Linnemann expands on the path to and then beneath the line of despair a bit, with particular reference to modernist theology and its philosophical roots. In so doing, she shows some of the ways in which Schaeffer’s work continues to be highly relevant and valid:

There is nothing in historical-critical theology that has not already made its appearance in philosophy. Bacon (1561 – 1626), Hobbes (1588 – 1679), Descartes (1596 – 1650), and Hume (1711 – 1776) laid the foundations: inductive thought as the only source of knowledge; denial of revelation; monistic worldview; separation of faith and reason; doubt as the foundation of knowledge. Hobbes and Hume established a thoroughgoing criticism of miracles; Spinoza (1632 – 1677) also helped lay the basis for biblical criticism of both Old and New Testaments. Lessing (1729 – 1781) invented the synoptic problem. Kant’s (1724 – 1804) critique of reason became the basic norm for historical-critical theology. Hegel (1770 – 1831) furnished the means for the process of demythologizing [through the Hegelian dialectic model for socio-cultural evolution] that Rudolph Bultmann (1884 – 1976) would effectively implement a century later – after the way had been prepared by Martin Kähler (1835 – 1912).

Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855) . . . reduced faith to a leap that left rationality behind. He cemented the separation of faith and reason and laid the groundwork for theology’s departure from biblical moorings . . . . by writing such criticism off as benign . . . .

Heidegger (1889 – 1976) laid the groundwork for reducing Christian faith to a possibility of self-understanding; he also had considerable influence on Bultmann’s theology. From Karl Marx . . . came theology of hope, theology of revolution, theology of liberation. [Biblical Criticism on Trial (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 2001), pp. 178 – 9.]

Now, Schaeffer was in Continental Europe across the 1950′s – 70′s as an orthodox, Dutch Reformed missionary to whom the students gasping for intellectual coherence in a sea of existentialist despair, came. Came in numbers amounting to a movement. To the point where the village he was based in made it into at least one popular song. A movement that still has consequences today, to the point where conservative Evangelical and pro-ID US presidential candidate Mrs Bachmann has noted that she has been influenced by his work. Which is what has brought out the rhetorical knife-men.

We can set them and their notorious trifecta tactics — distract, distort, and demonise to dismiss — to one side.

Back on topic.

Fundamentally, then, critical analysis of worldviews and their cultural implications was what Schaeffer was doing, and sufficiently well that when he passed away from cancer in 1984, major news magazines noted on his life work with a modicum of respect.

He was doing so in an atmosphere dominated by the great lights of learning in Europe who were building an existentialist worldview out of the wreckage of two world wars and the collapse of the academy as a leader in enlightenment (and under the distant looming shadow of the heirs of Marx and Lenin), given the dark age the horrible wars demonstrated beyond all doubt.

Don’t forget, one of the leading lights used to tell his students that the first thing is to make sure you don’t commit suicide. And, the description of a man who came to him, clinging to the fading memory of a “final experience” as an anchor for a sense of being in contact with something that can be seen as objective reality, as a drowning man clutches a straw, is iconic of his underlying compassion.

That should be respected, and we should reckon with Schaeffer’s successes as well as his limitations, whether or not we in the end agree with him on all or even most points.

Beyond that, the current Alinskyite attempt to turn him — live donkeys kicking a 26 years dead lion — into a strawmannish scapegoat to score cheap propaganda points off Bachmann et al, is despicable.

This brings us back to the debate over whether Schaeffer was right to talk of Aquinas as in effect innovator of the Nature/Grace dichotomy.

From the above corrected summary, we can see why many scholars say you can find antecedents, and it is arguable that Aquinas’ intent was to reach out to those who do not receive the scriptures by finding common ground, helping to close the nature-grace gap. But of course, Aquinas was the towering figure, who lived and taught in France and Italy, writing voluminously.

So, as fair comment: though Aquinas plainly sought to bridge the gap between reason and revelation, and sought to emphasise that God’s truth is true and will correct man’s errors, the gap in especially introductory remarks, where his framing of natural theology approaches did not — to my mind — sufficiently highlight Paul’s warning on the possibility of suppressing knowable truth about God on nature, and our experience of being minded, deciding, enconscienced, morally and rationally governed creatures, inadvertently helped to spread the nature-grace issue far and wide.

Thus, we come to the famous — and famously flawed — five ways (cf skeletisation here and discussions with videos here) for arguing to the reality of God under the project of natural theology. In later centuries, enlightenment era skeptical thinkers would use these as a pivot for arguing that in fact reason shows that there is no solid and indubitable evidence pointing to God. But also, long before that would happen, men were already setting nature up in its own right as an independent realm of thought, and soon nature would begin to eat up grace in their minds.

The better part of a millennium later, we therefore know the consequences of claiming “proofs” of God accessible to any reasoning man. Namely, through the rise of the skeptical spirit, anything — save “Science”! — that modern men are disinclined to hear that does not amount to an absolute proof beyond doubt to all rational minds is dismissed with the assertion “there is NO EVIDENCE.”

Of course, the suspicious gap on the subject of science reveals the selective hyperskepticism at work: matters of fact (and so also matters rooted in facts) are generally not demonstrable beyond all doubt on axioms acceptable to all. So, if you don’t like the conclusion and cannot overturn the logic, object to the premises. Even if otherwise similar matters would be accepted as a matter of course.

And that is why for instance we so often see objectors here at UD pointing to “assumptions” and dismissing reasoned arguments on inference to best explanation across live options.

So the key challenge –as say Simon Greenleaf highlighted in his classic treatise on Evidence, from Ch 1 on — is that one must have a reasonable and responsible consistency in standards of warrant on important matters of fact or matters rooted in facts. We thus see the standard of reasonable and consistent, albeit provisional warrant that appears in all sorts of serious contexts such as the courtroom, history, science [especially origins sciences], and many matters of affairs.

As Greenleaf explains in the just linked treatise, with particular emphasis on the courtroom:

The word Evidence, in legal acceptation, includes all the means by which any alleged matter of fact, the truth of which is submitted to investigation, is established or disproved . . . .

None but mathematical truth is susceptible of that high degree of evidence, called demonstration, which excludes all possibility of error [Greenleaf was almost a century before Godel] , and which, therefore, may reasonably be required in support of every mathematical deduction. Matters of fact are proved by moral evidence alone ; by which is meant, not only that kind of evidence which is employed on subjects connected with moral conduct, but all the evidence which is not obtained either from intuition, or from demonstration.

In the ordinary affairs of life, we do not require demonstrative evidence, because it is not consistent with the nature of the subject, and to insist upon it would be unreasonable and absurd. The most that can be affirmed of such things, is, that there is no reasonable doubt concerning them. The true question, therefore, in trials of fact, is not whether it is possible that the testimony may be false, but, whether there is sufficient probability of its truth; that is, whether the facts are shown by competent and satisfactory evidence. Things established by competent and satisfactory evidence are said to he proved . . . .

By competent evidence, is meant that which the very-nature of the thing to be proved requires, as the fit and appropriate proof in the particular case, such as the production of a writing, where its contents are the subject of inquiry. By satisfactory evidence, which is sometimes called sufficient evidence, is intended that amount of proof, which ordinarily satisfies an unprejudiced mind, beyond reasonable doubt. The circumstances which will amount to this degree of proof can never be previously defined; the only legal test of which they are susceptible, is their sufficiency to satisfy the mind and conscience of a common man ; and so to convince him, that he would venture to act upon that conviction, in matters of the highest joncern and importance to his own interest . . . .

Even of mathematical truths, [Gambler, in The Study of Moral Evidence] justly remarks, that, though capable of demonstration, they are admitted by most men solely on the moral evidence of general notoriety. For most men are neither able themselves to understand mathematical demonstrations, nor have they, ordinarily, for their truth, the testimony of those who do understand them; but finding them generally believed in the world, they also believe them. Their belief is afterwards confirmed by experience; for whenever there is occasion to apply them, they are found to lead to just conclusions. [A Treatise on the Law of Evidence, 11th edn, 1868 [?], vol 1 Ch 1, , pp. 45 – 46.]

The best overall approach to these matters, then — which BTW, instantly removes the force of accusations on question-begging — is to objectively compare the difficulties of competing explanations on responsible and well-informed abductive inference to best explanation per factual adequacy, coherence and explanatory power.

Through using that approach, we can look at the question of sound or at least trustworthy and reasonable worldviews foundations in light of the fact that we all have to start from key first principles of right reason, and also that every argument or inference has roots. Similarly, when we look at or touch something and accept it as real, we are accepting the testimony of fallible senses. So, there is a reasonable question as to why we should accept such.

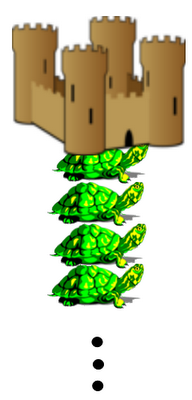

The logical structure then is: A, because of B. But B then needs C, . . .

It’s turtles, standing on turtles . . .

So, our choice is clear: (1) infinite regress [absurd], (2) circularity [question-begging], or (3) some cluster of first plausibles that define a worldview foundational faith-point.

Some of those first plausibles, we may believe, are self-evident: true and necessarily true once understood, on pain if immediate and patent self-contradiction. For instance, Josiah Royce’s “error exists,” is uncontroversially true. But also, if we try to deny it, we see that the denial is self contradictory as we have P: error exists, and Q: no error exists in front of us. At least one must be in error, and it is obviously Q, on the easily understood meaning of P. (And even if we were to insist that it is P, then P would be seen as true as it is self-referential.)

However, it is notorious that no worldview of consequence can be built up solely from self-evident start points. We are back at the project of comparative difficulties, and plainly neither infinite regress nor circularity are satisfactory. The only reasonable solution is to put the serious options on the table and compare them in light of what we know and can analyse.

I am fairly sure Schaeffer knew (probably from experience) that trying to debate Aquinas’ five ways and modern extensions or refinements thereof as though these are proofs accessible to all men, would only open up side tracks and strawman issues, frustrating serous progress.

So, instead, he went for Paul’s Mars Hill solution: blow up the system from its cracked foundations. In Paul’s case his subtle point is there in his opening remarks to the Areopagites in Acts 17: here we are in the most prestigious centre of learning and inquiry for our civilisation, and on the most important possible point of knowledge, the root of our being, the whole city has had to build and maintain a public monument to ignorance, the famous altar to the UNKNOWN God.

Kaboom!

(You may laugh him off and dismissively brush him aside, but that was the decisive blow; delivered in his opening words. The classical synthesis was irretrievably bankrupt, and this had been exposed, not only in the empty idols but the institutionalised ignorance of the learned on the most important issue of knowledge of all; the very root of our being.)

In Schaeffer’s work, especially through his partnership with Rookmaaker on the arts as an expression of foundational assumptions in a culture, he continually highlighted the key cracks in the foundations of modern thought (and what we now call post modern — more accurately, ULTRA-modern (as in push the volume knob to eleven, not just ten) — thought).

Actually, that is just what Paul did in Athens, when he pointed to the temples, idols on every street corner and the now famous altar to the unknown God.

As I have said already, Schaeffer read Paul with a profound insight.

There are ever so many deeply symbolic and revealing features in statues, architecture, paintings, poems, novels, the structures of government, the structures of laws and state documents, the way universities and institutions such as science operate, etc etc etc. So, the first task of worldview reformation is to throw the spotlight on the fatally cracked foundation of the proud monument to humanistic achievements, and toss in the already fuzed stick of analytical — note to strawmannising objectors: metaphor not call to violence — dynamite.

Kaboom!

The bankrupt system implodes and collapses.

(BTW, bin Laden, it seems, was trying that all too literally and with tellingly callous disregard for innocent life. Planes were invented, notoriously by Americans, as were Skyscrapers. So, he crashed the one into the other, to bring the latter down; hoping to crash the American Economy too, which was more nearly successful — a US$ 100 billion blow was no small potatoes — than we want to remember. Even the date was significant, 318 years, less one day, from the Jan Sobieski-led cavalry charge that broke the 1683 siege of Vienna in the strategic heart of Europe; and turned back the Islamist military thrust permanently, i.e UBL was advertising to those who knew, that he was bidding to take over from the last high water mark of the Caliphate.)

But, if you are going to analytically — never, never, never, literally!!! — blow up an old order you had better have a sound alternative.

And, that was Schaeffer’s key contribution: contrasting the reformation with the renaissance, he underscored how the former did not face the fatally revealing incoherence in what would become the line of despair as the gap in the system of thought that started with nature vs grace and ended with essentially deterministic mechanical reason vs freedom, proved unbridgeable.

So, he effectively took us back to the key point Paul was making on Mars Hill:

Ac 17: 22 . . . Paul, standing in the midst of the Areopagus, said: “Men of Athens, I perceive that in every way you are very religious. 23 For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription, ‘To the unknown god.’ What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you. 24 The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man,2 25 nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything. 26 And he made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, 27 that they should seek God, in the hope that they might feel their way toward him and find him. Yet he is actually not far from each one of us, 28 for

“‘In him we live and move and have our being’;3

as even some of your own poets have said,

“‘For we are indeed his offspring.’

29 Being then God’s offspring, we ought not to think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of man. 30 The times of ignorance God overlooked, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent, 31 because he has fixed a day on which he will judge the world in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed; and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead.”

32 Now when they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some mocked. But others said, “We will hear you again about this.” 33 So Paul went out from their midst. 34 But some men joined him and believed, among whom also were Dionysius the Areopagite and a woman named Damaris and others with them. [Of course from such slender beginnings, the gospel and the Christian faith founded on it peacefully prevailed in Greek culture, in the teeth of mocking dismissals, slanderous and spiteful caricatures, and waves of brutal persecution.] [ESV]

In short, He is there and is not silent.

So, we ought to listen to Him, and renew our souls and wider civilisation based on his wisdom, not our own fatally flawed misunderstandings.

What is the relevance of all this to the design theory debates?

1: It shows us that conceiving of design theory or wider science as a project in natural theology considered as “proving God” through the teleological argument is a predictably futile endeavour. Matters of facts and best explanations of facts simply are not matters of demonstrative proof.

2: It shows us that the exposure of the scientific and logical bankruptcy of imposed a priori Lewontinian materialism, is a first step to restoring sound science and sound science education, especially on origins.

3: It highlights the importance of worldviews thinking and analysis in preparing the groundwork for sound science, and for a soundly scientifically informed worldview.

4: It highlights that we should always be aware of how worldviews foundations and prestigious institutions of learning — whether the thinking of the dominating elites is sound or not — strongly shape how we think, what seems reasonable to us, how we make morally tinged decisions, and how our culture consequently develops, for good or ill.

5: It points out how dominant elites, even when the cracked foundations of their proud systems have been exposed, tend to dismiss and even ridicule criticism, so that real reformation tends to come from the margins and only after a time (pessimists say the old generation has to die off first) of controversy and cultural conflict — which can get pretty nasty — will a new order emerge.

6: We see also, in the face of Dionysius the Areopagite — remembered afterwards as the first Bishop of Athens and its patron saint — the importance of sponsorship from the elites or at least a sufficient power centre, for a new idea to succeed. (That’s why the old order tends to turn on any such with especial ferocity, as Dr Sternberg found out, and as the ID-friendly candidates for the upcoming US Election cycle will find out. [For that matter, this is part of why Paul himself was such a lightning rod in C1: he was, after all, “a Pharisee of the Pharisees.” TRAITOR!, they cry as they pounce on such.])

7: Last, but not least, it shows that reformation of an entrenched but fatally flawed order is possible. As is happening (ever so slowly, and with fits and starts) with science and science education in our day.

______________

So, while clearly the silly rhetoric that ID is creationism in a cheap tuxedo fronting a Christofascist totalitarian theocratic agenda is obviously a sticking plaster intended to cover up and distract from the fatal cracks in the foundation of a priori materialism imposed on science, science education and the wider culture, long-term we cannot simply plaster over a fatal structural defect.

The evolutionary materialist old order in our day is coming down, crashing due to its own fatal cracks. Already, we are hearing some pretty alarming creaks and pops, and things are beginning to sway and shake.

So, task number one for design theory is that we need to build a new order for science, on a sounder footing. (Or, perhaps, restore and update an older, sounder order, e.g. cf. Newton’s thoughts here and here.)

And, in so doing, we must be patient (and even compassionate) as the mortally embarrassed materialistic elite lashes out with desperate ferocity now that the fatal crack has had the cover-up plaster stripped off for those with eyes to see and ears to hear. END