There are some key motifs that often come up in discussions of design theory and linked ideas. Popperian, as captioned, has posed one of these. Notice, his view, that we GENERATE emotions, suggesting a dynamo churning away and generating electricity. That is, the motif that would reduce explanations to mechanisms is here revealed. I think it is well worth the pause to address it by headlining an in-thread response:

___________

>>Popperian, re:

why doesn’t someone start out by explaining how human beings generate emotions, then point out how the universality of computation does not fit that explanation. Effectively stating “It’s magic and computers are not magic doesn’t cut it.” Pushing the problem into an inexplicable mind hat exists in an inexplicable realm, doesn’t improve the problem.

Thanks for sharing your reflections (as opposed to the too common deadlocks on talking point games and linked typical fallacies that have become all too familiar . . . and informal fallacies are instructive on this matter . . . ), this always helps discussion move forward.

Second, pardon an observation: your response inadvertently shows how you have become overly caught up in the Newtonian, clockwork vision of the world.

Again, that reasoning by analogy or paradigmatic example — even though misleading — is instructive.

My fundamental point is that reasoning as opposed to blindly mechanical computation inherently relies on insight into meaning and a sense of structured patterns that suggest connexions. For instance, many informal fallacies pivot on how emotions are deeply cognitive judgements that shift expectations and trigger protective responses. So, if someone diverts attention from the focal topic and sets up then soaks a strawman in ad hominems and ignites, the resulting fears and anger will shift context and will contribute to inviting dismissal of the original matter without serious evaluation. Thus the protective heuristics have been manipulated.

Similarly, by shifting focus from the significance of insights and meaningful connexions to the scientific paradigm of Newtonian clockwork, then blending in the success of computer systems there is a shift away from a crucial difference that then leads to a reductionist, mechanistic tendency.

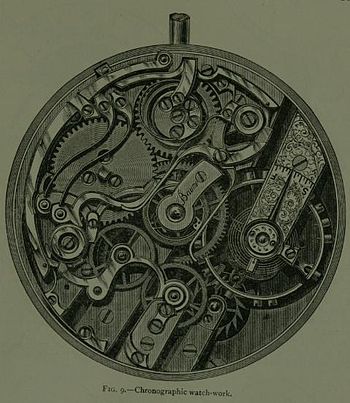

{Let us insert an illustration or a few, starting with an abstract generic dynamic-stochastic “mechanical” system model that shows blindly mechanical linkages at work:

As an application, let us look at a neural network, then a brain:

As an application, let us look at a neural network, then a brain:

We now zoom back, putting up a simple model of the two-tier control cybernetic loop, after Derek Smith:

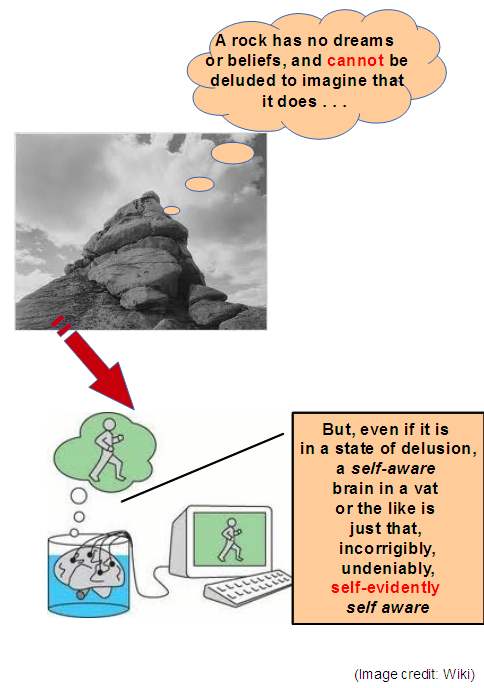

Such brings out that a mechanism can live in a wider context that is able to move beyond mechanistic dynamics, through a supervisory interface. Then, we need a contrast on computation vs contemplation, pivoting on the point that a rock has no dreams and that refining a rock into a computational substrate does not materially alter the blindly dynamic cause-effect bonds involved.

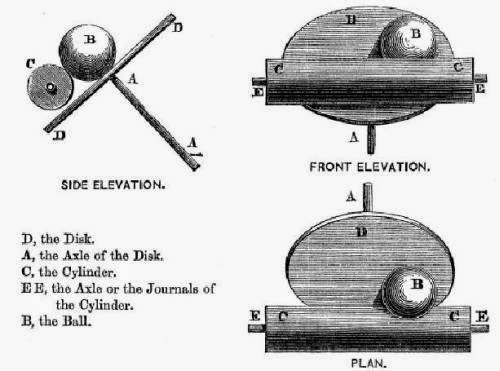

A Mechanical analogue computing framework will help, a ball and disk integrator that was formerly used in tide prediction and naval gunnery:

Here, the rate of accumulation of motion of the cylinder [viewed as input] depends on where the ball is relative to the centre of the disk, and so a dynamical input then is accumulated in the angular position of the disk effecting integration by moving from rate to cumulative degree of change. The components in this device are seen to be simply dynamical elements blindly interacting through cause-effect chains, it is the designer who is responsible for configuring to obtain reliable and accurate integration.

This continues if we move to a generic operational amplifier based analogue computer that solves differential equations in terms of voltages:

Little has changed if we move to a digital computer, which, suitably programmed can do much the same through taking inputs, storing intermediate results and data, processing through an execution unit involving an arithmetic and logic unit based on electronic circuits to generate outputs:

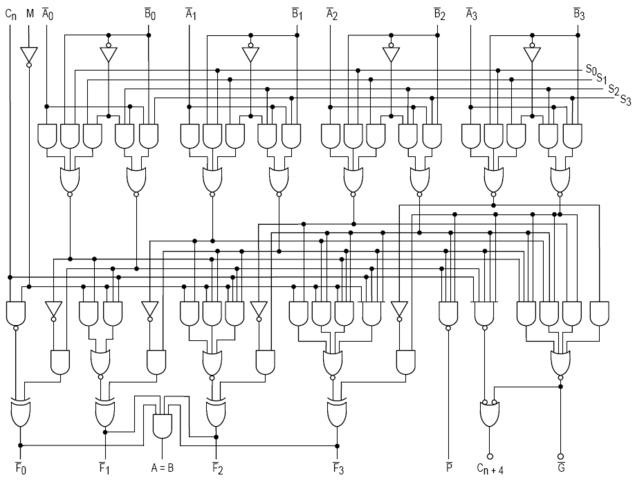

{u/D Jul 8: let me add a diagram of an ALU:}

In all these, we are subject to Leibniz’s remark in his Monadology, on the analogy of the Mill:

17. Moreover, it must be confessed that perception and that which depends upon it are inexplicable on mechanical grounds, that is to say, by means of figures and motions. And supposing there were a machine, so constructed as to think, feel, and have perception, it might be conceived as increased in size, while keeping the same proportions, so that one might go into it as into a mill. That being so, we should, on examining its interior, find only parts which work one upon another, and never anything by which to explain a perception. Thus it is in a simple substance, and not in a compound or in a machine, that perception must be sought for. Further, nothing but this (namely, perceptions and their changes) can be found in a simple substance. It is also in this alone that all the internal activities of simple substances can consist. (Theod. Pref. [E. 474; G. vi. 37].)

Thus, to try to reduce mind to mechanism seems rather like trying to get North by insistently heading West. This sets up the contrast:

The self-evident nature of such consciousness and linked experience is pivotal in opening up our minds to the reality of a different order of experiences.}

The self-evident nature of such consciousness and linked experience is pivotal in opening up our minds to the reality of a different order of experiences.}

The case of expert systems as was just discussed with Mapou is instructive:

reasoning and common sense etc are not blindly mechanical causal chains (perhaps perturbed by some noise) such as are effected in an arithmetic-logic unit, ALU or a floating point unit, FPU.

Instead, such are inherently based on insight into the ground-consequent relationship and broader heuristics that guide inference, hunches, sense of likelihood or significance of a sign etc. While we can mimic some aspects of such through sufficiently complex blends of algorithms — I have in mind so-called expert systems, these again are critically dependent on programming design and the structure and contents of data evaluated as knowledge and rules of inference, heuristics of “explanation” in response to query, etc.

Notice, the motif of evaluation by comparison while noting key differences? Thus, the implication that analogies — pivotal to inductive reasoning BTW — are prone to being over-extended. We know per widespread experience that there are patterns in the world, and that sch often can be extended from one case to another so if we think there is a significant similarity, we will extend. But this raises the question of implications of significant difference and adjusting, adapting or overturning the extension.

Such thought is imaginative, active, inferential, defeasible but verifiable to the point of in some cases strong empirical reliability, and more, much more. It is inherently non-algorithmic, pivoting on meaning, judgement and insight.

As I am aware of your problem with inductive reasoning (broad sense), I share Avi Sion’s point:

We might . . . ask – can there be a world without any ‘uniformities’? A world of universal difference, with no two things the same in any respect whatever is unthinkable. Why? Because to so characterize the world would itself be an appeal to uniformity. A uniformly non-uniform world is a contradiction in terms.

Therefore, we must admit some uniformity to exist in the world.

The world need not be uniform throughout, for the principle of uniformity to apply. It suffices that some uniformity occurs.

Given this degree of uniformity, however small, we logically can and must talk about generalization and particularization. There happens to be some ‘uniformities’; therefore, we have to take them into consideration in our construction of knowledge. The principle of uniformity is thus not a wacky notion, as Hume seems to imply . . . .

The uniformity principle is not a generalization of generalization; it is not a statement guilty of circularity, as some critics contend. So what is it? Simply this: when we come upon some uniformity in our experience or thought, we may readily assume that uniformity to continue onward until and unless we find some evidence or reason that sets a limit to it. Why? Because in such case the assumption of uniformity already has a basis, whereas the contrary assumption of difference has not or not yet been found to have any. The generalization has some justification; whereas the particularization has none at all, it is an arbitrary assertion.

It cannot be argued that we may equally assume the contrary assumption (i.e. the proposed particularization) on the basis that in past events of induction other contrary assumptions have turned out to be true (i.e. for which experiences or reasons have indeed been adduced) – for the simple reason that such a generalization from diverse past inductions is formally excluded by the fact that we know of many cases [[of inferred generalisations; try: “we can make mistakes in inductive generalisation . . . “] that have not been found worthy of particularization to date . . . .

If we follow such sober inductive logic, devoid of irrational acts, we can be confident to have the best available conclusions in the present context of knowledge. We generalize when the facts allow it, and particularize when the facts necessitate it. We do not particularize out of context, or generalize against the evidence or when this would give rise to contradictions . . .[[Logical and Spiritual Reflections, BK I Hume’s Problems with Induction, Ch 2 The principle of induction.]

We have a deep intuitive sense that there is order and organisation in our cosmos, which comes out in recognisable, stable and at least partly intelligible patterns that extend from one case to another.

Mechanism, of course is one such, and explanation on mechanism is highly successful in certain limited spheres. But by the turn of C19, there were already signs of randomness at work and by C20 we had to reckon with the dynamics of randomness in physics. In quantum mechanics, this is now deeply embedded, many phenomena being inextricably stochastic.

But reducing an irreducibly complex world tot he pattern of mechanism with some room for chance, is not enough.

The first fact of our existence is our self-aware, self-moved intelligent consciousness and interface with an external world using our bodies.

This too is a reasonable pattern, one that we see in action with others who are as we are.

From this we abstract themes such as intelligence, responsible freedom, agency, purpose and more, which we routinely use in understanding how we behave and the consequences when we act.

What has happened in our time is that due to the prestige of science, mechanism based explanations have too often been allowed to displace the proper place for agent based explanations, the place for art and artifice. This has even been embedded in a dominant philosophy that too often unduly controls science: evolutionary materialism.

There is even a panic, that if agency is allowed in the door, “demons” will be let loose and order and rationality go poof. This then often triggers fear, turf protection and linked locked in closed minded ideological irrationality.

The simple fact that modern science arose from in the main Judaeo-Christian thought that perceived a world as designed in ways meant to point to its Author, through involving at some level simple and intelligible organising principles or laws, should give pause. The phrase thinking God’s [creative, organising and sustaining] thoughts after him should ring some bells. (This is too often suppressed in the way we are taught about the rise of modern science.)

And of course, by way of opening the door to self-referential incoherence through demanding domination of mindedness by mechanism, evolutionary materialism falsifies itself. Haldane puts it in a nutshell:

“It seems to me immensely unlikely that mind is a mere by-product of matter. For if my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true. They may be sound chemically, but that does not make them sound logically. And hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms. In order to escape from this necessity of sawing away the branch on which I am sitting, so to speak, I am compelled to believe that mind is not wholly conditioned by matter.” [[“When I am dead,” in Possible Worlds: And Other Essays [1927], Chatto and Windus: London, 1932, reprint, p.209.

So, the very terms you use: “how human beings generate emotions,” is a giveaway.

We do not so much generate emotions and other consciously aware states of being, we experience them. And, to recognise and respect that fact without reference to demands for mechanistic reduction is a legitimate start-point for reflection.

All explanation is going to be finite and limited, so there will always be start-points. Starting from the realities of our interior-life experience is a good first point, and reflection on such shows that rationality itself (a requisite of doing science etc) crucially depends on insightful, purposeful responsible and rational freedom.

That which undermines such will then be self-defeating, and should be put aside.

Thus, the significance of Reppert’s development of Haldane’s point via Lewis:

. . . let us suppose that brain state A, which is token identical to the thought that all men are mortal, and brain state B, which is token identical to the thought that Socrates is a man, together cause the belief that Socrates is mortal. It isn’t enough for rational inference that these events be those beliefs, it is also necessary that the causal transaction be in virtue of the content of those thoughts . . . [[But] if naturalism is true, then the propositional content is irrelevant to the causal transaction that produces the conclusion, and [[so] we do not have a case of rational inference. In rational inference, as Lewis puts it, one thought causes another thought not by being, but by being seen to be, the ground for it. But causal transactions in the brain occur in virtue of the brain’s being in a particular type of state that is relevant to physical causal transactions

Trying to reduce this to blindly mechanistic physical cause-effect chains with perhaps some noise, is self-defeating.

In short, start-points and contexts for reasoning count for a lot.>>

___________

In short, our emotions are experienced as a facet of self-aware, responsibly free, rational agency. And, it is legitimate to begin from such a first fact of experience, especially as the mechanistic alternative shows every sign of breaking down when it becomes self-referential.

Perhaps, then, it is time for a fresh think that moves beyond say Crick in The Astonishing Hypothesis:

. . . that “You”, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behaviour of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. As Lewis Carroll’s Alice might have phrased: “You’re nothing but a pack of neurons.” This hypothesis is so alien to the ideas of most people today that it can truly be called astonishing.

. . . and similar patterns of thought?

Philip Johnson’s reply seems to have a bit of bite to it. Namely, that Sir Francis should have therefore been willing to preface his works thusly: “I, Francis Crick, my opinions and my science, and even the thoughts expressed in this book, consist of nothing more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.” Johnson then acidly commented: “[[t]he plausibility of materialistic determinism requires that an implicit exception be made for the theorist.” [[Reason in the Balance, 1995.]

Surely, it is time for fresh thinking? END