A few days ago, The Week published a pro-evolution article with the paradoxical title, “Why you should stop believing in evolution” by Keith Blanchard, a former editor-in-chief of Maxim magazine who is now the chief digital officer of the World Science Festival. Evolution, argued Blanchard, isn’t something we believe in, but something we simply grasp: “You either understand it or you don’t.” Blanchard then proceeded to demonstrate that he doesn’t understand the very theory he advocates: his article is riddled with scientific errors and non sequiturs.

I’m not the first person to criticize Blanchard’s article on scientific grounds. That honor belongs to Glenn Branch, Deputy Director of the National Center for Science Education, whose article, Five Quibbles for Blanchard was published on the NCSE Website on August 7, and re-posted on the Richard Dawkins Foundation Website on the same day. But only one of the errors identified by Branch could properly be described as a scientific error; the rest are either philosophical, historical or related to Blanchard’s background beliefs: curiously for an evolutionist, he appears to retain a vestige of belief in the Great Chain of Being, as evidenced by his strange assertion that humans are becoming “less bestial” over time, coupled with his frank acknowledgement that he would rather not be related to monkeys – a startling remark for a Darwinist to make, and one that Branch indignantly declared “could almost make me go ape!”

The scientific error identified by Glenn Branch related to Keith Blanchard’s limited understanding of the mechanisms of evolution:

Blanchard seems to equate evolution, in the sense of universal common ancestry — “Go back far enough, and you’ll find an ancestor common to you and to every creature on Earth” — with natural selection. Or, what’s about as problematic, he seems to identify natural selection as the one and only mechanism of evolution... Granted, for the purposes of Blanchard’s piece, there was no particular reason to invoke any of the other primary mechanisms of evolution (genetic drift, gene flow, mutation). But since his concern was primarily with universal common ancestry, it wouldn’t have been particularly difficult for him to write in such a way as to avoid reinforcing these misconceptions.

Blanchard’s “selectionist” model of evolution

Personally, I think Branch is being too charitable to Blanchard here. Blanchard’s understanding of evolution is undeniably selectionist, as evidenced by the following passage in his article:

When … new traits are advantageous (longer legs in gazelles), organisms survive and replicate at a higher rate than average, and when disadvantageous (brittle skulls in woodpeckers), they survive and replicate at a lower rate.

That’s a little oversimplified, but the general idea. As advantageous traits become the norm within a population and disadvantageous traits are weeded out, each type of creature gradually morphs to better fit its environment.

Branch might be interested to know that evolutionary biologist P.Z. Myers recently criticized South Carolina’s state science standards for inaccurately asserting that “[b]iological evolution occurs primarily when natural selection acts on the genetic variation in a population and changes the distribution of traits in that population over multiple generations.” In a follow-up post, Myers went on to explain that this statement reflects an out-dated selectionist model of evolution, in which all mutations are regarded as either advantageous or deleterious. The modern view of evolution, explained Myers, is strikingly different from that of Darwin:

First thing you have to know: the revolution is over. Neutral and nearly neutral theory won. The neutral theory states that most of the variation found in evolutionary lineages is a product of random genetic drift. Nearly neutral theory is an expansion of that idea that basically says that even slightly advantageous or deleterious mutations will escape selection — they’ll be overwhelmed by effects dependent on population size. This does not in any way imply that selection is unimportant, but only that most molecular differences will not be a product of adaptive, selective changes.

In other words, most mutations have no effect on fitness. And mutations that have only a slight positive or negative effect on fitness are invisible to natural selection. Blanchard’s model of evolution is over forty years out-of-date.

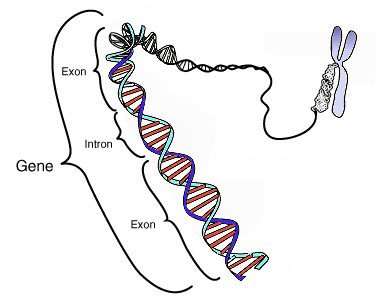

Blanchard’s faulty understanding of genes

|

But this error pales into insignificance, when compared to Blanchard’s bald (and inaccurate) assertion about the role of genes:

Genes, stored in every cell, are the body’s blueprints; they code for traits like eye color, disease susceptibility, and a bazillion other things that make you you.

This crude understanding of genes was roundly debunked in a recent article in the Huffington Post by Professor Agustin Fuentes, titled, DNA Is Not a Blueprint: How Genes Really Work (June 8, 2012):

Genes play an important role in our development and functioning, not as directors but as parts of a complex system. “Blueprints” is a poor way to describe genes. It is misleading to talk about genes as doing things by themselves. There are very few instances of direct gene-to-trait scenarios, even in well known “genetic” disorders. Traits emerge from the interactions of genes and a range of developmental and environmental influences, and similar DNA sequences often produce slightly different outcomes. Our DNA influences who we are, but not in a linear or easily described manner. (See here for more.)…

Genes contain information, but the actual relationship between genes and our bodies and behavior is complicated…

There is little evidence to support any one-to-one relationship between genes and behavior.

Blanchard’s gradualism

There’s more. Blanchard asserts that new species are the result of an accumulation of gradual changes over the course of time:

The very notion of “species” is even a little misleading — a discrete-sounding artifice created for the convenience of people who live about a hundred years. If you had eyes to see the big picture, and could watch life change on a geologic time frame, you’d see constant gradual change, as generations adapt to circumstance…

Pile on enough eons, and tiny pidgin (sic) horses gradually become rideable by gradually less hairy apes.

Blanchard should know that this gradualistic view of evolution has been publicly rejected by leading biologists, including evolutionary biologist Eugene Koonin, who states in his best-selling work, The Logic of Chance: The Nature and Origin of Biological Evolution (FT Press, Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2011):

Gradualism is not the principal regime of evolution. (p. 398)

Evolutionary biologist P. Z. Myers concurs with this view: he cited this very quote from Koonin’s book in a recent post. In a 2007 review of the late Stephen Jay Gould’s posthumously published magnum opus, Punctuated Equilibrium, Myers wrote:

Gould and Eldredge proposed punctuated equilibrium as a paleontologist’s view of the history of life: they were describing the paleontological data available at the time pointing out that there was no geological evidence to support Charles Darwin’s belief that species evolved gradually. Time has shown them to be correct, and their observations are now accepted by most biologists as a accurate account of evolutionary history.

Artificial selection as evidence for macroevolution

Blanchard compounds his errors by arguing that artificial selection proves that macroevolution (evolution at or beyond the species level) can occur: although evolution normally proceeds at a glacial pace, humans can speed it up artificially, leading to “evolution turbocharged by human intervention” which effectively creates new species. The implication is clear: if human breeding over a relatively short scale of several thousands of years can accomplish all this, how much more so can natural selection, operating over the course of millions of years?

We invented the dog, starting with wolves and quickening the natural but poky process of evolution by specifically selecting breeding pairs with desirable traits, gradually accentuating particular traits in successive populations. Poodles, Rottweilers, Great Danes, Hollywood red-carpet purse dogs — all this fabulous kinetic art was created, and continues to be created, by humans manually hijacking the mechanism of evolution.

There’s a saying that a picture is worth a thousand words. Here’s a photo of the skeleton of a Great Dane, next to a Chihuahua:

|

Apart from size, there’s not much of a difference in the skeletons, is there?

Or as geneticist Jeff Tomkins (who is now a creationist) trenchantly puts it in an online article titled, Artificial Selection and Dog Breeding is Not Evolution (April 25, 2013):

You can push dog genetic variability in whatever direction you want, and you will only get dogs. It’s not a situation where small changes are adding up over long periods of time to vertically transform and produce something completely different than a dog. Rather, dog breeding (artificial selection) is a matter of exploiting and manipulating inherent variability within the dog gene pool, called horizontal genetic variation. Dog breeding doesn’t vindicate evolution on a grand scale or provide proof for natural selection.

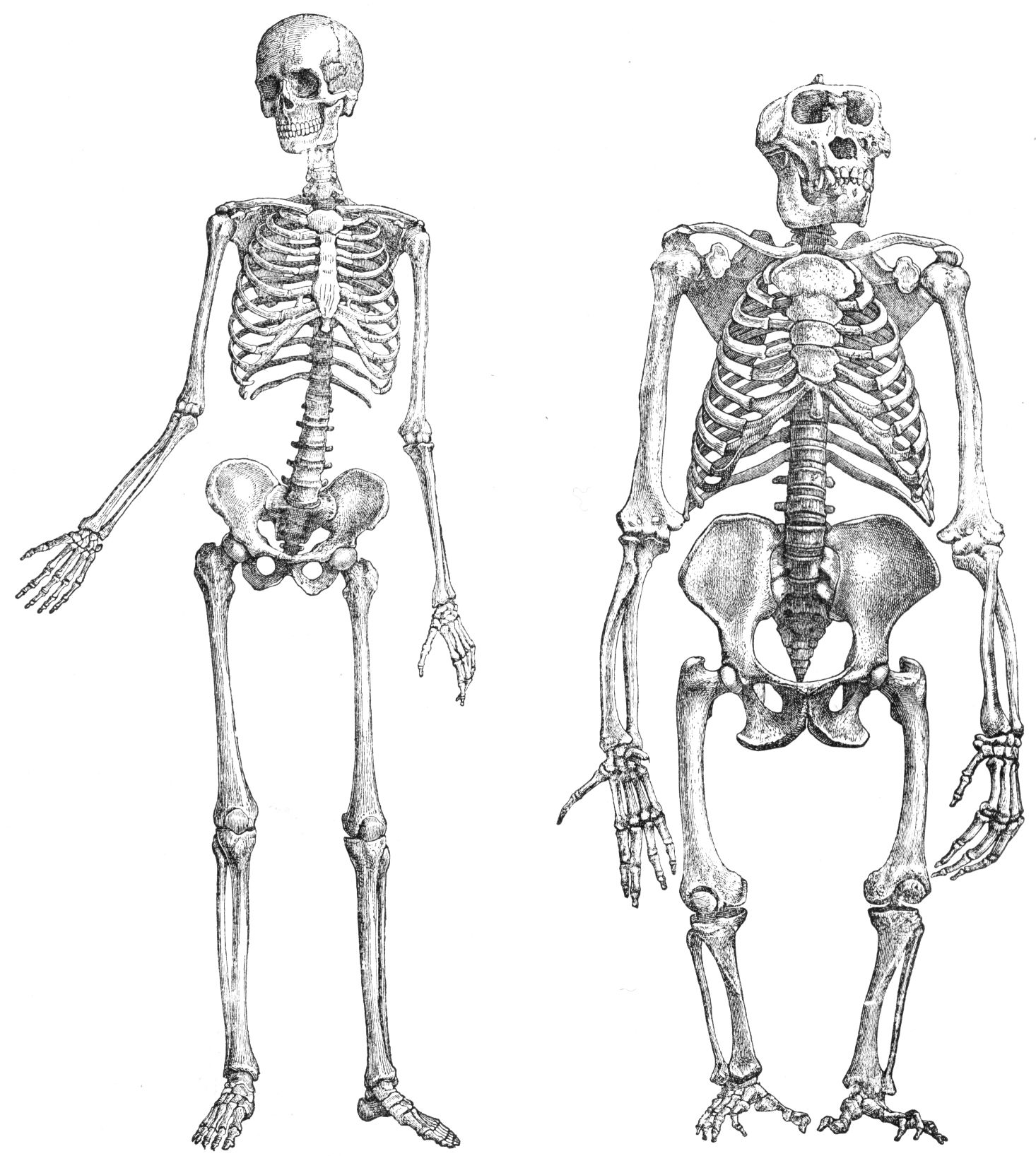

“What about human beings and great apes such as the chimpanzee and gorilla?” you might ask. Here’s another picture, showing a human skeleton and a gorilla skeleton. Not so similar, are they?

|

Chimpanzees and gorillas are agreed by scientists to be man’s closest living relatives. The anatomical differences between humans and chimpanzees, which are quite extensive, are conveniently summarized in a handout prepared by Anthropology Professor Claud A. Ramblett the University of Texas, entitled, Primate Anatomy. Anyone who thinks that a series of random stepwise mutations, culled by the non-random but unguided process of natural selection, can account for the anatomical differences between humans and chimpanzees, should read this article very carefully. What it reveals is that an entire ensuite of changes, relating to the skull, teeth, vertebrae, thorax, shoulder, arms, hands, pelvis, legs and feet, not to mention the rate of skeletal maturation and method of locomotion, would have been required, in order to transform the common ancestor of humans and chimps into creatures like ourselves. Given the sheer diversity of changes that would have been required, it is surely reasonable to ask whether an unguided process, such as Darwinian macroevolution, could have accomplished this feat over a period of a few million years.

Blanchard’s bungled examples of human vestigial traits

Blanchard concludes his argument with an appeal to human vestigial traits as evidence for evolution:

Why do you have sharp canine teeth? An appendix? Hair under your arms? If your body was designed for its current usage, there’s a lot of inefficiency there. If it seems, rather, to be in the process of becoming less … bestial, well, that’s because it is.

Blanchard’s artless statement that humans are becoming less bestial over time has been critiqued on scientific grounds by Glenn Branch, a vocal defender of human evolution, who comments:

Humans are still beasts … and no amount of evolution is going to change that.

If one accepts Branch’s naturalistic assumptions, then his logic is impeccable.

But the alleged vestiges cited by Blanchard do not pass muster. To begin with, the function of canine teeth, according to leading dentists, is “holding, grasping, and tearing food.” Because canine teeth are especially durable, they are referred to by dentists as “the cornerstone of the mouth.” What’s more, the shape and size of canine teeth have changed little since the time of Australopithecus africanus, three million years ago, as these images show. (It is true that Neanderthal man had larger canines than modern man, but his incisors were larger as well, and the large size is apparently due to the very heavy wear on teeth in prehistoric times.)

|

The human appendix was shown several years ago to play a vital function in the human body. Loren G. Martin, professor of physiology at Oklahoma State University, has listed various likely functions for the appendix on Scientific American‘s website (October 21, 1999), including:

- being “involved primarily in immune functions”;

- “function[ing] as a lymphoid organ, assisting with the maturation of B lymphocytes (one variety of white blood cell) and in the production of the class of antibodies known as immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies”;

- helping with “the production of molecules that help to direct the movement of lymphocytes to various other locations in the body”;

- “suppress[ing] potentially destructive humoral (blood- and lymph-borne) antibody responses while promoting local immunity”;

- and finally, it is “an important ‘back-up’ that can be used in a variety of reconstructive surgical techniques.”

The idea that the appendix functions as a storehouse for beneficial microbes that help fight off infections in the gut is becoming more widely accepted, even among evolutionary biologists, as science reporter Susan Perry acknowledges in an article for MinnPost titled, The appendix has a healthful purpose, evolutionary evidence suggests (February 18, 2013). She points out that according to a recent study, people without an appendix were four times more likely to experience a recurrence of an infection caused by the bacterium C. difficile than people who still had their appendix. C. difficile kills an estimated 14,000 Americans each year. In her article, Perry explains how the myth that the appendix had no function came to be accepted in the first place, thanks largely to the speculations of Charles Darwin:

Charles Darwin helped popularize the idea that the appendix was a vestigial structure. During his lifetime, only humans and other great apes were known to have an appendix. This led Darwin to hypothesize that the appendix was an evolutionary artifact — a remnant of the days when our ancient ancestors needed a larger cecum (the pouch-like beginning of the large intestine) to store bacteria to break down plant tissues. Darwin believed that when those ancestors switched to a more easily digestible fruit-based diet, the cecum shrank — and the appendix became unnecessary.

Perry goes on to cite a recent article by Colin Barras in Science Now (February 12, 2013), which states that no less than 50 species of mammals are now considered by scientists to have an appendix, and that for most of these species, there was no sign of a dietary shift triggering the evolution of the appendix. Nevertheless, Barras maintained that since the ape appendix appeared at around the time when our ancestors switched diets, it “may have” originally evolved for that reason. In logic, this kind of reasoning is known as post hoc, ergo propter hoc (“after this, therefore because of this”). And even if the origin of the ape appendix could be linked to dietary changes, the fact that it continues to play a vital role in the human body means that its value as a piece of evidence for human evolution is vastly diminished.

The last item cited as evidence for human evolution by Blanchard is “hair under your arms.” Reading about this one made me smile: even the zealously pro-evolution Wikipedia admits: “The evolutionary significance of human underarm hair is still debated.” There are at least three hypotheses which attempt to account for why we have hair under our armpits: it may (i) aid the wicking of sweat away from the skin, (ii) reduce friction between the thorax and upper arm, or (iii) facilitate the release of sex pheromones. A recent article by Cristen Conger on HowStuffWorks explains underarm hair in terms of sexual selection: “The hair in those areas traps and amplifies those odors, like loudspeakers that amplify your body’s chemical siren song of attraction.” Well, maybe – but what does that prove about our ancestry? The simplistic notion, popularized by Blanchard, that underarm hair is a relic of our simian past has not the slightest evidence to support it.

Conclusion

I could go on, but I’d like to conclude this article with a final observation: Keith Blanchard doesn’t have a science degree. His LinkedIn profile lists him as having a two year tech degree in Electronic Technology, which he obtained in 1975. Let us freely grant that the man’s skill set looks quite impressive. Nevertheless, the fact remains that a man without a science degree has no place writing an article on evolution in a popular online magazine like The Week. It’s simply presumptuous.

For the record, I happen to believe in the common descent of humans and apes, based in large part on the fact that the gaps in the hominin fossil record have been shrinking steadily over the last few decades – including the gap that was alleged to exist between Australopithecus and Homo ergaster/erectus. But after having read assiduously about human evolution for more than 40 years, I can categorically state that anyone who thinks we’ve got it all sewn up is just nuts. We know very little of the genetic changes that triggered the explosive growth and structural reorganization of the human brain over the past few million years, and we are in no position at the present time to estimate the statistical likelihood of these changes. (Remember: we’re talking about the most complicated machine in the universe, folks. Computers don’t hold a candle to it, and the brains of other animals appear to be qualitatively different in terms of their mental capacities.) Consequently, we have no right to assume that the evolution of the human brain and body, if it occurred, was an unguided process, as modern-day evolutionary biologists overwhelmingly do, or that it occurred without the need for any special intervention, as Blanchard appears to believe. (The only possible role he allows for God at the end of his article is setting “the rules of evolution.”)

It is a great pity that Keith Blanchard believes that macroevolution is as obvious as “gravity, or the roundness of Earth.” As readers of this blog will be aware, one of the world’s top chemists, Professor James Tour, thinks there’s no scientist alive today who understands macroevolution. Perhaps Blanchard, in his arrogance, thinks that Professor Tour is also guilty of covering his eyes and ears, like everyone who questions macroevolution. What I would suggest that Blanchard do instead is try to find out why intelligent people come to doubt evolution.