In his reply to my latest post, Edward Feser took me to task for focusing exclusively on the teleological argument instead of his favorite argument: the cosmological argument (which includes St. Thomas Aquinas’ first, second and third ways). Today, I’ve decided to remedy that defect. In 2013, Professor Feser gave a talk titled, “An Aristotelian Proof of the Existence of God”. The talk, which is just over an hour long, is well worth viewing, and Feser rebuts popular objections to the argument towards the end, at 50:40. However, I would strongly urge readers to peruse Feser’s post, So you think you understand the cosmological argument? (July 16, 2011) before watching the video.

http://vimeo.com/60979789

For those who don’t like watching videos, I’ve summarized Professor Feser’s argument in 20 steps below. I’ve included brief comments on each step, but in this post, I’m going to let Feser do most of the talking.

It will be recalled that Professor Feser claims to possess an ironclad argument of the existence of God, as understood within classical theism. He maintains that it is possible “conclusively to establish” the existence of a Supreme Intellect, not merely as the best or most rational explanation for the world around us, but as “the only possible explanation even in principle” (Aquinas, Oneworld, Oxford, 2009, pp. 111-112). Whereas Aquinas’ Fifth way deals with the regular behavior of things, as manifested by their built-in tendencies, Aquinas’ First, Second and Third ways focus on changes occurring within things, and ultimately on the fact that they exist at all. What ties change and existence together is the Thomistic principle that nothing potential can actualize itself. Feser contends that if we apply this principle consistently, we can deduce with metaphysical certainty the existence of a purely actual First Cause, which possesses the key divine attributes: eternity, incorporeality, maximal perfection, unity, perfect goodness, omnipotence and omniscience. What’s more, Feser contends that his argument is a relatively straightforward one, which makes no fancy scientific assumptions: in this case, all he is assuming is the reality of change and the existence of a material world. If Feser’s argument works, then Intelligent Design arguments for a Designer of Nature are redundant: for according to Feser, not only life, but every kind of natural object existing within the cosmos, can be shown to have been designed. But if the argument fails, Feser, who has ridiculed Intelligent Design proponents for years for making use of probabilistic arguments, will have to publicly eat his words. I’ll let my readers judge for themselves whether Feser’s arguments are successful. However, in my opinion, the cosmological argument set out in Feser’s one-hour talk on video contains so many obvious logical errors that I could not in all good conscience recommend showing it to atheists.

Let me state up-front that I am not claiming in this post that Aquinas’ cosmological argument is invalid; on the contrary, I consider it to be a deeply insightful argument, and I would warmly recommend Professor R. C. Koons’ paper, A New Look at the Cosmological Argument and Professor Paul Herrick’s lengthy essay, Job Opening: Creator of the Universe—A Reply to Keith Parsons (2009). (I note, by the way, that Professor Koons is a Thomist who defends the legitimacy of Intelligent Design arguments.) I myself have defended a “transcendental” version of the cosmological argument in previous posts (see here and also here). Rather, what I am asserting is that Professor Feser’s claim to have developed a knockdown demonstration, not only of the existence of God, but also of all of the key Divine attributes is decidedly premature. His argument, as it stands, simply does not accomplish what it sets out to do.

For what it’s worth, though, I think Feser’s rebuttals (at 50:40 in the video) of the standard objections to the cosmological argument by the philosophers Hume and Kant are pretty convincing, and Feser handily disposes of scientific objections based on Newton’s First Law and quantum mechanics, so I won’t waste time on them in this post.

I’d also like to add for the benefit of non-Thomistic readers that Feser does not assume in his argument that the world had a beginning; nor does he assume that the world can be treated as one giant object. Rather, Feser insists that his argument can be applied to a single entity existing within the world, no matter how small it is (even a hydrogen atom!), and that we can successfully deduce the existence and attributes of God from that entity.

A question of accuracy and logical holes

|

A Kenwoth C509 truck from Moree, NSW, Australia. Image courtesy of Berichards and Wikipedia.

For the record, I will not be retracting anything I say in this post. Professor Feser may try to accuse me of misrepresenting his argument, but readers can view the video for themselves and see that I have set it out with painstaking clarity. And even if there were some small point in Feser’s argument that I have gotten wrong, the holes in Feser’s logic are so wide that anyone could drive a truck through them. These logical errors dwarf whatever tiny errors I may have made in setting down Feser’s argument. Focusing on the latter and ignoring the former would be tantamount to straining at gnats and swallowing camels. I note in passing that Feser has yet to respond to my critique of his revamped version of Aquinas’ Fifth Way (see here for a short, 3,000-word summary). Today, however, we’ll be focusing exclusively on Feser’s latest version of the cosmological argument.

STAGE I: An argument for a purely actual First Cause

Step 1. Change occurs – e.g. qualitative change, change in location, quantitative change and substantial change. This cannot be coherently denied. (Objection: What if an evil demon is deceiving you about the existence of an external world, as Descartes imagined? Reply: Even if this were true, change still occurs in your mind. Also, even if you somehow manage to intellectually convince yourself that change is impossible, you refute your own claim in doing so, because you’ve changed your mind.)

My comments:

1. Obviously I accept Feser’s first premise, but I don’t like his defense of it: he’s conceding too much here by saying that even change occurring only in your mind would still be enough for the argument to work. It isn’t: premises 7 and 11 explicitly assume the existence of material things.

2. Some physicists have argued that the Wheeler-de Witt equation, which reconciles quantum physics and general relativity by leaving out time altogether, proves that time is an illusion. Other physicists, such as Lee Smolin, emphatically disagree. Wikipedia describes the equation as “an attempt to mathematically meld the ideas of quantum mechanics and general relativity, a step toward a theory of quantum gravity” (italics mine) which sounds pretty tentative to me. So I think Feser has every right to ignore this scientific objection to premise 1.

Step 2. Change can only occur in things which have potentials that can be actualized. (Parmenides’ philosophical argument against the possibility of change mistakenly assumes it involves something coming from nothing. However, it makes much more sense to view change as involving coming from a potential, and a potential is not nothing.)

My comment: I’m in full agreement with Feser here.

Step 3. Change requires a changer, because it is the actualization of a potential. The actualization of a potential can only be explained by something actual.

My comment: Feser’s argument contains a sound metaphysical insight here. It should be noted, however, that the “something actual” doesn’t necessarily have to be external to the thing being actualized; it could be, for instance, that one property of a thing (let’s call it P1) explains the actualization of another property (P2) of the same thing.

Step 4. When a potential in a thing is being actualized, sometimes the actualizer is undergoing change itself. That is, it is being actualized – in which case, the change occurring in the actualizer itself requires a changer, in order to account for it.

My comment: Feser should have been more careful here. What he should have said is that if the actualizer’s actualization of a potential necessarily (or essentially) involves the actualizer’s undergoing change, then that change requires a changer. And as I pointed out in my comments on premise 3, that changer may turn out to be just another property of the thing being changed. We haven’t shown the need for an external cause yet.

Step 5. We often explain changes in terms of prior changes: the room gets cold because you switched on the air conditioner earlier, which happened because you felt hot, which was caused by heat reaching you from the sun, and so on. This is a linear series (a.k.a. an accidentally ordered series). A linear series of changes extending back in time might have no first member, as the past might be infinite in duration. (Note: Feser’s argument, like that of Aquinas, does not assume that the universe had a beginning.)

Essentially ordered hierarchical series (which need not go back in time, although sometimes they may) are fundamentally different from linear series, in that the later members of the chain have no power to act, except insofar as they derive that power from prior members.

A traditional cup of cappuccino coffee resting on an orange desk or table. Professor Feser argues that a desk’s power to hold up a coffee cup is a power it derives from the floor it rests on, from the foundation supporting the floor, and ultimately from the Earth, which supports the foundation. Image courtesy of Coffeecupgals and Wikipedia.

Example 1: Suppose there’s a coffee cup on your desk. The coffee cup on your desk is being held up by the desk, which is supported by the floor, which is supported by the foundation of your house, which is supported by the Earth. This series need not go back in time: the coffee cup is sitting on your desk at that moment only because it is being held up at that moment by the desk, floor, foundation and ultimately by the Earth. The desk has no power of its own to hold up your coffee cup; its power to do so depends on the floor, foundation and Earth beneath it.

Example 2: Or consider a lamp above your head, which is held up by a chain, which is held up by the fixtures in the ceiling, which in turn is held up by the walls, which are held up by the foundation, which is once again held up by the Earth. The chain, fixture, ceiling, walls and foundation have no power of their own to hold anything up; their power is derived from that of the Earth. They are in that sense instruments, just as it’s not a brush that paints a picture, but rather the painter who uses the brush that paints the picture. Likewise with the coffee cup resting on the desk, the desk, floor, and foundations are instruments of the Earth. Thus in a hierarchical series, each member is thus being actualized by prior members, and is only capable of acting insofar as it is being actualized by those members.

In other words, every member of a hierarchical series, apart from the first, has its power only in a derivative way. Thus in a hierarchical series of causes, the later members of the series are instruments. In a linear series, on the other hand, the members of the series have their own causal power, and can continue acting, even if prior members cease to exist and/or operate.

My comment: Feser’s distinction between linear and hierarchical series is expressed with admirable lucidity, but his physical examples of a hierarchical series are flawed. The causal powers of the desk (and by the same token, of the floor and foundation) are grounded in its nature as a material wooden object. They are not in any way, shape or form derived from the Earth which supports the desk, floor and foundation. If the Earth ceased to exist, the desk would continue to have the causal powers it possesses; what it would lose is a place where it can exercise those powers in the way it did before.

Think about it. How does the desk hold the coffee cup up? From a physicist’s point of view, it would be better to ask: why doesn’t the cup fall through the desk? In a nutshell, there’s a force, related to a system’s effort to get rid of potential energy, that pushes the atoms in the cup and the atoms in the desk away from each other, once they get very close together. The Earth has nothing to do with the desk’s power to act in this way (which is rooted in its nature as wood): it simply happens to provide support for the desk when it does so act. The same considerations apply to the lamp. [Note: for some follow-up comments on the coffee cup illustration, see comments 14 and 15 by kairosfocus, who is a physicist, and my response on the philosophical implications of his comments, here.]

Step 6. A hierarchical series of causes has to have a first member, while a linear series of causes does not. Here, “first” does not mean “temporally first,” but rather, something whose power to act does not derive from anything else: something which is not the instrument of anything else, which has its causal power in a primary or built-in way, and which can impart causal power without anything being imparted to it.

For example, a paintbrush does not have the power to move itself: even if its handle were infinitely long, it would still be an instrument. A desk, floor and foundation have no power of their own to hold up a coffee cup, except insofar as they derive it from the earth. Even an infinite series of desks would not be able to support the cup. We would ordinarily think of the sequence cup-desk-floor-foundation-earth as simultaneous, but we do still have a series of actualizations in the hierarchical series. The potential of the cup to be three feet off the ground is actualized by the desk it rests on; the desk’s potential to hold up the cup is actualized by the floor; and so on.

My comment: Once again, Feser’s metaphysical insights are valid, but the physical illustrations are marred by faulty science. Feser’s statement that even an infinite series of desks would not be able to support the cup is absurd: if there were no Earth, there would be nowhere for the cup to fall towards, and there would be no need for it to be “kept up.” (In any case, the desk doesn’t keep the coffee cup “up,” so much as away: the atoms comprising the wood of which the desk is made keep the atoms in the cup from getting too close.) The paintbrush example is better: the brush has no power of its own to paint a picture. However, if it were infinitely long, it could certainly keep moving at a constant velocity indefinitely without the need for any external assistance, but in the manner of a linear rather than a hierarchical series: each atom would “tug” the one adjacent to it, like an infinite series of train cars. (Yes, I think that’s possible, too: it’s another linear series.) In this case, each atom’s power to “tug” at the next atom in no way derives from that of the atoms further up the causal chain; rather, this power is a simple consequence of the atom’s having the momentum it does at that point in time.

Halite crystals, commonly known as rock salt. Professor Feser argues that material things such as salt crystals require a cause for their continuation in existence. Image courtesy of W. J. Pilsak and Wikipedia.

Step 7. Hierarchical series are more fundamental to reality than linear series, because a linear series of causes presuppose the existence of an underlying hierarchical series. Things can undergo change only because they exist. But for any material thing, we can legitimately ask: what makes it continue to exist? Appeals to past causes in a linear series fail to explain anything, because although they explain why the thing came to exist, they don’t explain why it continues to exist. To say that the things exists by default, because nothing has come along to break up or destroy that thing yet, still doesn’t explain what keeps it in existence at any moment. After all, it has the potential to either exist or not exist. Appeals to the structural arrangement of the internal components don’t work either, as they fail to explain why those components are not arranged differently. Hence the chain of explanation for things’ existence must be a hierarchical chain.

My comment: Feser seems to be arguing here that anything which is composed of parts requires an external cause to explain its continuation in existence. An internal explanation (e.g. mutual attraction) will not suffice, says Feser, since if part A depends on part B and part B depends on part A, then we have a vicious explanatory circle. Hence there must be something outside the object which holds it together and explains its continuation in existence. I think the charge of circularity is wrong: instead of A depending on B and B on A, we can say that A is attracted to B because of B’s power to attract A; while B is attracted to A because of A’s power to attract B. (Think of the sodium and chloride ions in a salt crystal, such as the one pictured above.) There seems to be nothing circular about this account. All it presupposes is that A and B exist, and that each has an active power to attract oppositely charged objects – which is why, once they come together, they stay together.

One might also argue that if the parts of an object are physically incapable of being separated, then there’s no need to ask what holds them together.

Nevertheless, I think Feser would still want to argue that it is always legitimate to ask about any composite object: “Why aren’t its components arranged differently from the way they are now?” From a metaphysical standpoint, I sympathize with Feser here, but a skeptic might see no need to ask this question.

Finally, and most tellingly, all that Feser has argued so far is that composites require an external cause to hold them together. In order to complete his proof, Feser also needs to be able to show that natural objects’ ultimate constituents (elementary particles) require an external cause, to keep them in existence, even if they are structurally simple.

Note: A reader named Box pointed out a major flaw in one of Feser’s illustrations in a comment below. Feser argued that coffee is kept in existence by its constituent molecules, which in turn are maintained in existence by atoms, which are held together by subatomic particles. But as Box points out, this is not a hierarchical causal chain because the subatomic particles are not distinct from the coffee: rather, they comprise the coffee.

Step 8. Because the chain is hierarchical, the First Cause of things’ existence must be one which can actualize the potential for things to exist, without having to have its own existence actualized by anything. This Cause doesn’t have any potential for existence that needs to be actualized in the first place: it is always actual. You might say that it doesn’t have actuality, but that it is Pure Actuality. Such a First Cause could not have had a cause of its own. Being devoid of potentiality, there is nothing in it that could have needed actualizing. Such a cause is an Unmoved Mover, Uncaused Cause or Unactualized Actualizer: a purely actual Actualizer of the existence of things.

My comment: There is a LOGICAL FLAW in Feser’s argument here. Remember what I said in my comments to premise 4 above? All Feser has shown is that there must be an Actualizer whose power to actualize does not need to be activated (or actualized) by anything else. That and nothing more. Feser has not shown that this Actualizer is devoid of potentiality; all he has shown is that even if it has some unactualized potentialities, it doesn’t need to activate any of these potentialities when activating other actualizers. So for Feser to describe this Unactualized Actualizer as Pure Actuality is an unwarranted logical leap.

What’s more, Feser overlooks the possibility that the Actualizer may be self-actualizing: it may for instance have an active potentiality P1 that is actualized by the exercise of some other active power P2 that it possesses, where the latter can operate autonomously, without the need to be actualized by the exercise of any other power. So even within the First Actualizer, there may still be potentialities that need to be actualized; all we can say is that not all of its active powers can be like that. At least some of its active powers are not activated by the exercise of any other power.

Finally, a skeptic might object that Feser is employing the term “cause” in his argument for God’s existence, without bothering to define what the term “cause” means, or how it would apply to the First Cause. However, Feser might reply that his definition of cause is a constructive one, which emerges from the argument when we consistently apply the metaphysical principle that nothing potential can actualize itself. This principle, according to Feser, is completely general: once we learn it, we can meaningfully apply it, even beyond the world of sense experience. Thus Feser rejects Kant’s dictum that concepts derived from sense experience are can only be meaningfully applied within the physical world. On this point, I am fully in agreement with Feser.

STAGE II: Why this First Cause is fittingly called “God”

Step 9. The First Cause is the Ultimate Cause of the existence of things: it keeps them in existence at any moment at which they exist at all.

My comment: There is a HUGE LOGICAL FLAW at this point in the argument. Feser declares that the First Cause is the Ultimate Cause of the existence of things; but recall that his argument proceeds from the consideration of a single entity, not the universe as a whole (as some versions of the cosmological argument do). So far, all we can say is that Feser’s First Cause (or Causes!) keeps one or more things in existence. That’s a long way from being “the Ultimate Cause of the existence of things.”

Step 10. Since the Cause of the existence of things is Pure Actuality, it is immutable and therefore eternal (outside time).

My comment: Since Feser has failed to show that the First Cause or Unactualized Actualizer is Pure Actuality, he cannot demonstrate that it is immutable.

Step 11. Since material things are essentially inside time, the First Cause must be immaterial and incorporeal.

My comment: Feser hasn’t yet shown that the First Cause is outside time, so the conclusion does not follow. However, it could be argued (fairly, I think) that a Cause which does not have to undergo change in order to change other things must be outside time, so I’ll let Feser’s premise 11 stand.

Step 12. A defect in a thing is a privation: a failure to realize a potential that is built into the nature of that thing. Hence the First Cause, being purely actual, cannot be defective. Something is perfect to the extent that its potentials are actualized. Hence a purely actual Cause must possess maximal perfection.

My comment: Leaving aside the fact that Feser hasn’t demonstrated that the First Cause is Pure Actuality, the real problem here is that Feser is guilty of EQUIVOCATION in his use of the term “maximal perfection.” Does it mean: (a) possession of perfect attributes only (with no defects), or (b) possession (in some way or other) of all perfections? Feser seems to want to say (b), but he has only argued for (a).

The yin-yang symbol. Professor Feser argues that dualism is false: there can only be one Uncaused Cause. Image courtesy of Gregory Maxwell and Wikipedia.

Step 13. Such a Being must also be unique. For there to be two such beings, there would have to be something that one has and the other lacks. There can be no such differentiating feature with something purely actual. For if there were two such beings, one would have to possess a perfection that the other lacks. But as we have seen, any first cause is completely devoid of privation and purely actual. Hence there can only be one First Cause.

My comment: Feser’s conclusion is a complete non sequitur. His conclusion only follows if the First Cause possessed all possible perfections.

I might also point out that not possessing a perfection is different from having a privation, or lacking a perfection you should possess. Having four legs is a perfection for a sheep, but not for a snake. While a three-legged sheep lacks a leg, it would be utterly wrong to say that a snake lacks legs. So we can easily conceive of a First Cause #1, possessing powers P1, P2 and P3, and a First Cause #2, possessing powers P4, P5 and P6, where First Cause #1 is the kind of being for whom P4, P5 and P6 are not a perfection, while First Cause #2 is the kind of being for whom P1, P2 and P3 are not a perfection. Hence although each First Cause would not possess certain powers that the other First Cause possessed, it would lack none, and would therefore be totally devoid of privation and hence purely actual. On this scenario, there could be two purely actual beings.

Step 14. The first cause possesses the attribute of unity: there cannot in principle be more than one purely actual Cause.

My comment: Since Feser has failed to establish that there is only one First Cause, it follows that he has also failed to demonstrate that there can only be one, in principle. And even if we were to grant his claim that the First Cause is purely actual, it would still need to be established that Pure Actuality is necessarily unique.

Step 15. Is the First Cause all-powerful? Since the cause of the existence of things is Pure Actuality itself, rather than being just one actuality among others, That which is the Source of the power everything else has, has all possible power. It is, in short, omnipotent.

My comment: “Almighty” is not the same as “omnipotent.” It is one thing to say that the First Cause is capable of doing everything that can be done; quite another to claim that the First Cause is capable of doing everything logically possible.

Step 16. The First Cause must also be perfectly good, as it realizes its potentials to the fullest possible extent. A purely actual Cause of the world cannot be said to be bad in any way, as it lacks nothing and is perfect.

My comment: The reasoning here is correct, from an Aristotelian standpoint. The definition of “goodness” here is a purely internal one: the First Cause is good insofar as it’s a perfect specimen – indeed, the only possible specimen – of the kind of Being it should be. However, nothing is implied here about what ordinary people generally call “moral goodness”; indeed, we have yet to establish that the First Cause is even capable of moral behavior. Nor have we defined what “moral goodness” would mean for such a Being.

Le Penseur, in the Jardin du Musée Rodin. Professor Feser argues that the Uncaused Cause must possess something like our ability to think. Image courtesy of Daniel Stockman and Wikipedia.

Step 17. Is the first cause intelligent? Intelligence in Scholastic philosophy involves three basic capacities:

(i) the capacity to grasp universal abstract concepts (e.g. “man”);

(ii) the capacity to combine these capacities into abstract thoughts (e.g. the thought that all men are mortal);

(iii) the capacity to infer one thought from others, as when you reason from “All men are mortal” and “Socrates is a man” to “Socrates is mortal.”The first capacity is the most fundamental. It involves having a form or pattern in the mind that is the same as the form or pattern that the concept is about. Intellectual activity can be defined as the capacity to have the abstract form or pattern of a thing, without being that kind of thing.

My comment: Feser is putting forward a suasive definition of intelligence here. So, how persuasive is it?

To begin with, there’s a problem with the first capacity: the ability to have or hold concepts. Feser is implicitly appealing to a spatial metaphor here: that of the mind as a container of concepts. Concepts are said to be in the mind. But it’s not clear what the term “in” would even mean, for an incorporeal Being which is not composed of parts.

Another problem with defining intelligence primarily as the ability to have or possess abstract concepts is that this definition overlooks the element of following a rule, which is an integral part of intellectual activity. For example, you cannot draw valid inferences unless you follow the rules of logic, and even when you apply a concept, you are bound by certain rules or conventions which govern what statements you can meaningfully utter: for instance, you can say that your bike has wheels, but you cannot meaningfully say that a joke has wheels.

Finally, Feser neglects to mention that thought is – insofar as we are capable of entertaining thoughts and drawing inferences – inherently language-bound. So if the First Cause is intelligent, it must be capable of using some sort of language. What kind? Hmmm… interesting question.

Step 18. Causation is essentially a matter of giving or transferring something. But a cause cannot give what it does not have to give. The Principle of Proportionate Causality says that whatever is in the effect must be in the cause in some way – either formally, virtually or eminently.

A cause can have what is in the effect either formally (as when the cause actually instantiates the form or pattern generated in the effect), virtually (as when the cause has the power to generate the form produced in the effect by acquiring that form from elsewhere), or eminently (as when a cause has the power to independently generate the form produced in the effect). To cause a thing to exist is to cause something having a certain form or pattern. But the purely actual Uncaused Cause is the cause of every possible thing that might exist, and hence the cause of every possible form – every possible cat, every possible tree, every possible stone. It is for that reason the cause of every possible form that a thing might have. But as we’ve seen, what is in the effect must also be in the cause – either formally, virtually or eminently. Hence the forms of patterns of things in the purely actual Cause of things must exist in a completely universal or abstract way, because this Cause is the cause of every possible thing having that form or pattern.

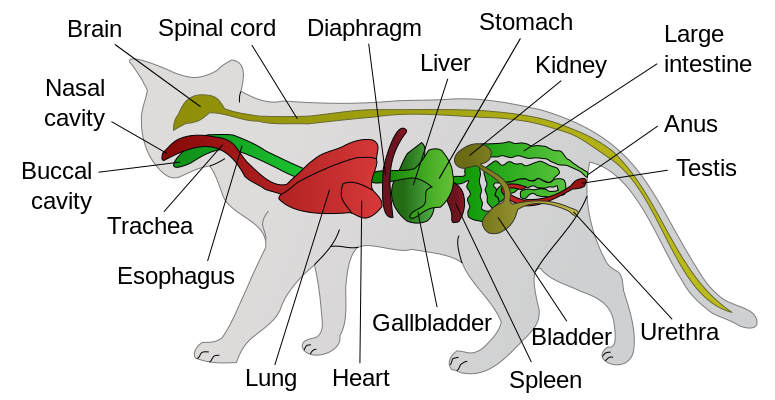

The general anatomy of a male cat. In his talk, Feser does not address the question of how the complex concept of a cat is “contained in” the simple Mind of the First Cause, let alone how this simple Mind contains knowledge of all possible states of affairs involving cats. Image courtesy of Persian Poet Gal and Wikipedia.

But to have forms or patterns in that abstract way is simply to have that capacity which is fundamental to intelligence: having a form or pattern within you, without being that kind of thing. Moreover, the purely actual Cause of things is not only a cause of their existence, but of their relationships to other things: it’s not only the cause of man but of all men being mortal; and it’s not only the cause of this cat, but of this cat’s being on this mat. Hence there must be some sense in which these effects exist in their purely actual First Cause, and it must be in a way that has to do with the combination of the forms or things that exist in that cause.

That is to say, these effects (states of affairs) must exist in the purely actual First Cause in something like the way in which thoughts exist in us. We not only have concepts, but we also have complete thoughts. In the same way, the purely actual Cause of things is not only the cause of all entities but of their relations to one another. So there must be something corresponding to those facts or states of affairs in the Cause of the world – which means that there must be something analogous to a complete thought in us. So what exists in the things that the purely actual Cause is the cause of, pre-exists in that cause, in something like the way that the things that we make pre-exist as ideas or plans pre-exist in our minds when we make them. These things thereby exist in that cause eminently and virtually, even if not formally.

Thus the Cause of things is not itself a cat or a tree, but it can cause a cat or a tree, or anything else that might exist.

My comment: Feser is equivocating here, again. When he says that the First Cause is the cause of every possible thing that might exist, what kind of “might” does he have in mind? Is he talking about logical, metaphysical or physical possibility? If he means that the First Cause is capable of causing every logically possible instance of a thing – e.g. every kind of cat whose existence was logically possible – that would indeed indicate that the First Cause has purely abstract concepts. But all that Feser has actually established – assuming the First Cause to be unique, for argument’s sake – is that the First Cause is capable (in some sense) of generating all those cats that are capable of being generated in our world – in other words, all individual cats whose existence is physically possible. Would the First Cause need to have a purely abstract concept of a cat in order to do that? Maybe, maybe not. But we’ll let that pass.

There’s another, deeper problem. Feser has distinguished three ways in which something in the effect can exist in a cause: eminently, virtually and formally. So, in which way are abstract concepts in the First Cause? Feser says that thoughts are in the First Cause eminently and virtually, even if not formally. Would he say the same of abstract concepts, as well? If so, then what becomes of his notion that concepts involve “having a form or pattern within you”? What does “eminently within” or “virtually within” mean?

Finally, Feser is guilty of equivocation once again when he states that not only all possible beings, but also all possible states of affairs (i.e. relationships between those beings) must be in the First Cause – eminently and virtually, even if not formally. Does he mean “all logically possible states of affairs” or all physically possible states of affairs, or something in between?

Nor does Feser tell us what it means to “eminently contain” a possible state of affairs. In particular, does “eminent containment” require a mental representation of these state of affairs in the Mind of the First Cause? If so, then it would seem that the First Cause has to be composite – which is contrary to the claims of classical theism. But if not, then it seems Feser is claiming the First Cause has non-representational knowledge – which sounds like an oxymoron. (One way out of this dilemma, which I have proposed on previous occasions, would be to jettison the notion that knowledge of complex states of affairs has to be “in” the Mind of the First Cause – maybe it has immediate access to these facts, without containing them. This would preserve Divine simplicity.)

Another solution – which Feser would probably favor – is that the First Cause has a more general, implicit representation of these states of affairs in its Mind: for instance, maybe it knows them simply by knowing itself as a Being capable of generating these states of affairs. But that would mean that nothing in its Mind corresponds to the complex concept of a cat. Feser might reply that the First Cause understands the concept of a cat negatively, by grasping those positive perfections belonging to Pure Being which a cat lacks. But insofar as a cat lacks multiple perfections, even this negative concept of a cat would have to be complex.

Feser’s reasoning in Step 18 is also marred by vagueness of his assertions. He declares that there must be something corresponding to those facts or states of affairs in the Cause of the world – which means that there must be something analogous to a complete thought in us. But why should a representation of states of affairs in the world require language? And if it doesn’t, why should we ascribe thought to the First Cause?

It gets worse. Feser goes on to say that what exists in the things that the purely actual Cause is the cause of, pre-exists in that cause, in something like the way that the things that we make pre-exist as ideas or plans pre-exist in our minds when we make them. Plans imply the existence of foresight. We have yet to establish that the First Cause has complete knowledge even of the present, let alone the future.

Step 19. There is nothing that exists or could exist that is not in the range of this cause’s thoughts. In that sense, this cause is all-knowing or omniscient.

My comment: Assuming (very generously) that Feser has established that the First Cause is intelligent, the argument in this premise proves only that the First Cause is capable of thinking about any possible state of affairs – not that it actually thinks about every possible state of affairs. And once again, the argument does not specify what kind of possibility we are talking about here: logical, metaphysical or nomological (physical).

Step 20. Hence the First Cause must have the key divine attributes: eternity, incorporeality, maximal perfection, unity, perfect goodness, omnipotence and omniscience.

My comment: Remarkably, love is not even listed among these attributes. And for all practical intents and purposes, that’s the only one most people are really interested in. It’s also what the Bible says God is (1 John 4:8). I note also that omnibenevolence is traditionally listed among the attributes of God, but Feser does not mention it in his talk.

Conclusion

Apart from his newly released Scholastic Metaphysics (Editions Scholasticae, 2014, ISBN-13 9783868385441), which I have not yet seen, Feser’s video talk, given in 2013, is his most recent defense of the cosmological argument for the existence of God. Feser aimed very high, and in my judgment, his argument falls a long way short of accomplishing its goal.

Flawed arguments can often be salvaged, however. I found it curious that in his talk, Feser said nothing (as far as I could tell) about the Scholastic distinction between essence and existence. And while he repeatedly described the First Cause as Pure Act, he did not mention the neo-Platonic notion of God as Pure Being. Presumably this was because his talk was titled, “An Aristotelian Proof of the Existence of God.” What that suggests to me is that Feser’s cosmological argument depends at least as much on the philosophy of Plato and his disciples as on Aristotle: indeed, one might liken Plato and Aristotle to the two wings of an aircraft: unless both of them are present, the aircraft simply cannot fly.

Finally, for those readers who can get hold of it, I would suggest that they read his article, “Existential Inertia and the Five Ways” (Australian Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 85, No. 2, 2011). Although it was written two years before Feser gave his video talk last year, it is in many ways a clearer exposition of the Thomistic proofs.

Feser, to his credit, has courageously stepped up to the plate and put his money where his mouth is: he has given a public defense of what he regards as an Aristotelian proof of the existence of God. He spoke to a public audience of people who were highly sympathetic to his views, and he had a full 65 minutes to make his case for the existence of the God of classical theism. Unfortunately, the premises of his argument are significantly flawed, as they currently stand; a lot of philosophical spadework will be required to make the argument watertight. In the meantime, I would ask Feser to acknowledge that the “proof” of God’s existence and attributes which he puts forward is, in its present condition, nothing of the sort, and that he may be better-advised to aim for a lower standard of proof than the ironclad metaphysical certitude which he has sought. Certainty beyond reasonable doubt has a lot to be said for it, as an evidential standard, and there are plenty of good arguments for God’s existence which achieve that level of certainty.

UPDATE

Two weeks ago, I emailed Professor Feser, notifying him “as a courtesy” about the above article. Although I pulled no punches in my criticisms, I was respectful towards Feser throughout my article, as readers can verify for themselves. I expected a serious and thoughtful response from Feser, but I was deeply disappointed when I read his reply, accusing me of being a “science dork,” of writing “like a central casting New Atheist combox troll,” and even of channeling Bill Nye the Science Guy! This was very odd, as my major criticisms of Feser’s argument (which I highlighted in red letters, so nobody could miss them) had nothing to do with science: they had to do with Feser’s logical errors, especially in steps 8, 9, 12 and 13.

It is a fallacy to argue from “There must be an Actualizer whose power to actualize does not need to be actualized by anything else” to “There must be an Actualizer which is totally devoid of potentiality.” It is a fallacy to argue from “There must be an Ultimate Cause for the existence of any particular thing” to “There must be an Ultimate Cause for the existence of all things.” It is an equivocation to claim that the First Cause possesses all perfections, when one has only established that it possesses perfect attributes only (with no defects). It is a non sequitur to claim that the First Cause must be unique because it possesses all perfections, when one has only established that the First Cause is devoid of imperfections.

These were the fallacies that I was hoping Feser would acknowledge and address. Instead, what I got was a lengthy rant from Feser accusing me of being “logorrheic” (which is odd, as his own post was very lengthy), of writing an inordinate number of posts (fifteen, by his count) in response to his blog articles (which is even more curious, as his own blog reveals that as far back as 2010, he had already written far more than fifteen posts critical of Intelligent Design), of reading his argument uncharitably (which is very strange, as I took pains to point out that “flawed arguments,” such as Feser’s, “can often be salvaged,” and praised his 2011 article, “Existential Inertia and the Five Ways” as “a clearer exposition of the Thomistic proofs” than his one-hour talk), and of being obsessed with finding faults in his scientific illustrations (despite the fact that I expressly wrote that while I considered physical examples of a hierarchical series to be flawed, “Feser’s distinction between linear and hierarchical series is expressed with admirable lucidity.”

It appears that in finding fault with Feser’s scientific examples, I touched a raw nerve. Feser responded that his examples were intended merely as illstrations, adding that “I’ve made the same point many times (e.g. here,

here,

here,

here,

and here).” Fair enough, but when one is writing about essentially ordered series of hierarchical causes, one should be able to give a single valid example of such a series. That’s all I ask.

Astonishingly, after harping on my scientific criticisms of his argument (which were of relatively minor significance), Feser then went on to say that he would not be reading the rest of my post, in which I exposed the logical flaws in his argument:

Well, don’t worry Vince, I won’t be accusing you of misrepresenting me in whatever it is you have to say in the remainder of this latest post of yours. I haven’t bothered to read it.

What’s more, even after I wrote to Feser, urging him to address the logical flaws in his argument, and even identifying the steps in which they occurred, Feser continued to refuse to read them, writing that after reading my objections to his physics, “it was not worth reading the rest.” To cap it all, he then accused me of crying wolf, when drawing readers’ attention to the logical flaws in his argument.

Well, I’m very sad that Professor Feser has taken my post so personally, but as I’m a very imperfect human being myself, it is not my place to sit in judgment of him. Instead I will simply wish him all the best for the future, and pray that God continues to guide him in the excellent work he has done, in defense of the faith.