Here and here? To ask such a question is to answer it, once you know the background: Of course not.

Here and here? To ask such a question is to answer it, once you know the background: Of course not.

This week we noted the centenary of the passing of Alfred Russel Wallace, co-discoverer of natural selection, who accepted the evidence for design in nature and was banished from Darwin’s circle in consequence.

From the BBC, we learn:

On 7 November 2013, the Natural History Museum in London is unveiling a statue of the man who co-discovered the theory of evolution by natural selection.

David Attenborough advises us that he considers Wallace the “most admirable character in the history of science.”

Toffs and ‘crats think they can afford to say that now.

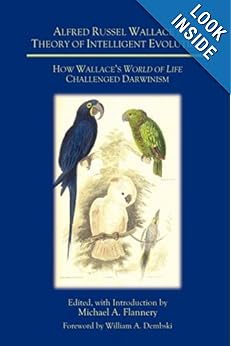

As science historian Michael Flannery explains, a true picture of Wallace would be an embarrassment just now because

Its is a fact worth more than a little notice that Wallace had considerably more actual field experience than Darwin. While Wallace communed with nature and lived with the indigenous peoples of South America and later the Malay Archipelago studying everything from beetles and butterflies to parrots and orangutans, Darwin was at home cutting his biological teeth on barnacles. … Receipt of a letter from the other end of the planet at comfortable Down House showed Darwin in bold relief–here was Wallace the man of nature suffering from a malarial fever on a remote island writing to the comfortably domesticated Darwin about a theory that the Down House patriarch coveted as his and his alone, a member of Victorian high society who (except for his five-year voyage on The Beagle) had little first-hand experience with species save for his precious barnacels. All told, Wallace would accumulate twelve years of intimate intercontinental field experience, more than twice Darwin’s.

Also, why Darwin banished Wallace:

It was on the relation of natural selection to man that Wallace and Darwin would part company. In the April 1869 issue of The Quarterly Review Wallace, in a review of Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology and his Elements of Geology, declared that the human brain simply could not be accounted for by the operations of natural selection. He concluded his essay by stating, “Let us fearlessly admit that the mind of man (itself the living proof of a supreme mind) is able to trace, and to a considerable extent has traced, the laws by means of which the organic no less than the inorganic world has developed. But let us not shut our eyes,” he added, “to the evidence that an Overruling Intelligence has watched over the action of those laws, so directing variations and so determining their accumulation, as finally to produce an organization sufficiently perfect to admit of, and even to aid in, the indefinite advancement of our mental and moral nature” (394).

Those harboring notions of theistic-friendly Darwinian evolution need only to honestly admit the harsh reaction of the Down House patriarch to reassess their position. Darwin was appalled, scratching a triple underscored NO in the margin. Darwin told Lyell he was “dreadfully disappointed” in Wallace. Writing to Wallace, Darwin “groaned” over his position on man and evolution ending with, ”Your miserable friend, C. Darwin.”

…

Wallace opens his chapter by agreeing that natural selection accounts for much in the natural world, even the human form. The unique properties of the brain, however, are another matter. Wallace proceeds to demonstrate that, Darwin’s elaborate speculations in his Descent of Man (1871) notwithstanding, particular features of the human intellect simply could not have been the product of natural selection. Humanity, in short, is more than the mere refinement of traits found in lower animals. Mathematical skill, musical and artist appreciation and ability, humor, the capacity for metaphysics, none of these could be explained by way of natural selection processes. This forms the context for his main thesis, namely, that humanity and its distinctiveness cannot be explained by Darwin’s strict materialism.

So far, nothing we’ve seen from the immense labours of evolutionary psychology has proven Wallace wrong.

Wallace was also just a more decent man than Darwin’s followers, actually, and that told against him in a Darwinizing world. For example,

One thing I learned from reading Flannery’s biography of Wallace is that he developed his passion for land reform as a result of his experiences as a land surveyor, surveying in areas where traditional common lands had been enclosed and country folk were left without resources. Opinions differ as to whether the move was necessary, but the suffering wasn’t.

… Darwin’s inner circle was very much pro-enclosure:

One can unearth scattered evidence in Spencer, Huxley and Sumner that they would temper the harshness of their doctrines. I suggest dismissing most of the temperance as double-talk. One may interpret the forked tongue of ambiguity by finding the bottom line. What all three did was devote major effort to defending concentrated ownership of land, even in the radically extreme and novel form it took in England after the vast enclosure movements of the early 19th Century.

Also unusually for his time and unlike Darwin, Wallace was not a racist. He had lived long enough among traditional peoples to know better.

Anyway, statues are expensive, but way cheaper than discussions based on fact.