Says Scientific American. How do we know? We don’t. It just that many known exoplanets are gas giants which may also have large moons, as ours do: “And if they do, moons—not planets—may be the most common home for life in the universe.” (paywall)

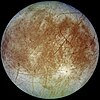

There may well be water on the exoplanets, of course. Consider, for example, Jupiter’s Europa:

The ice-world Europa has long been seen as a good potential home for extraterrestrial life. That candidacy just got much stronger: it was reported last month that astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope to keep an eye on Europa have spotted evidence of volcanic activity.

Europa’s ice crust, which is thought to be a few kilometres thick, covers a watery ocean over 100 kilometres deep. Nobody knows whether life exists in that ocean, but if it does it would require a source of energy. As so little sunlight penetrates the ice crust, that would have to come from within. That is why the signs of intermittent plumes of vapour erupting from the ice have so excited hunters of extraterrestrial life: it suggests that some kind of life-giving volcanic energy is at work inside the icy moon.

But here’s the problem: The big recent news has been the discovery of highly complex life forms (comb jellies) from 600 million years ago near the beginning of the life we actually know.

Fire and ice are not the source of this complexity, which was wrongly assumed to have been fuilt up over the intervening period. So what is? If we knew that, we would be further ahead.

See also:

Don’t let Mars fool you. Those exoplanets teem with life!

“Behold, countless Earths sail the galaxies … that is, if you would only believe …”