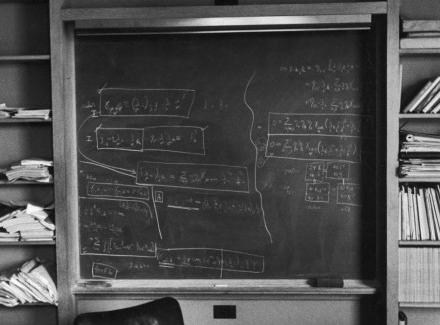

Below, is a picture of Einstein’s chalkboard at Princeton as he left it — and you should see his bookshelves and desk, too!

What does this have to do with the now so commonly dismissed laws of thought, especially the law of non-contradiction?

A lot.

AKA, one cannot wisely saw off the branch on which s/he is sitting.

What does that mean?

We can start from the proverbial main tools of the great theoretical physicists of 100 years ago when quantum physics was emerging: chalk-boards, chalk, and — of course — what they had between their ears.

So, they used distinct scratch marks with definite meanings, to clarify, analyse and communicate what they were thinking.

(Some, proverbially, had “chalkboards in their heads” that in some cases were capable of three-dimensional, moving images and even simulations! Hence, Einstein’s favourite thought-experiments, and the equally proverbial physicist’s intuition that has so often proved fruitful. At the extreme, proverbially, was the engineer, Tesla, who — as the stories handed down go — could build, assemble and run a new electric machine in his head; then after a few weeks, take it apart and inspect the wear patterns to adjust his design. Fancy software that with considerable effort we use to model and visualise today is crude by comparison! But, it at least helps those of us who have more modest equipment between the ears to walk in the footsteps of the true giants.)

The trick is, that as all of this physical and mental chalk-dust work interacts with the experienced world, it deeply, inextricably embeds the classic laws of thought into the experimental and analytical work of science. So, to then imagine that such results can undermine or dismiss those laws of thought is to saw off the branch on which even quantum physicists must sit.

That’s why, in UD’s brand new Weak Argument Corrective, no 38, on LNC and quantum theory, frequent commenter and occasional UD contributor Stephen is quoted:

Scientists do not use observed evidence to evaluate the principles of logic; they use the principles of logic to evaluate such evidence.

That’s a key insight, and, sadly, it is too often overlooked. (Indeed, there was a hot debate at and surrounding UD over the past few weeks on just this topic.)

So, let us now read and discuss the new WAC 38, and the more detailed supplementary discussion. END