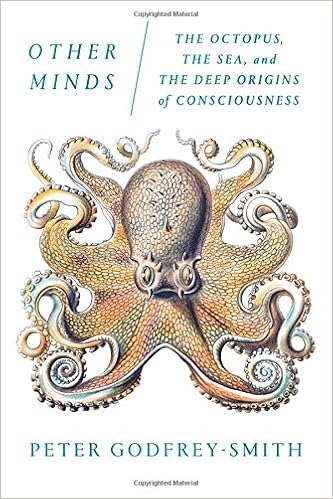

No, we did not make this total confusion up. From Olivia Goldhill, discussing Peter Godfrey-Smith’s Other Minds: The Octopus, The Sea, andthe Deep Origins of Consciousness at Quartz:

No, we did not make this total confusion up. From Olivia Goldhill, discussing Peter Godfrey-Smith’s Other Minds: The Octopus, The Sea, andthe Deep Origins of Consciousness at Quartz:

Octopus research shows that consciousness isn’t what makes humans special

There’s some uncertainty about which precise ancestor was most recently shared by octopuses and humans, but, Godfrey-Smith says, “It was probably an animal about the size of a leech or flatworm with neurons numbering perhaps in the thousands, but not more than that.”

This means that octopuses have very little in common with humans, evolution-wise. They have developed eyes, limbs, and brains via a completely separate route, with very different ancestors, from humans. And they seem to have come by their impressive cognitive functioning—and likely consciousness—by different means.

Indeed? Where is the octopus space program?

It’s important to figure out whether consciousness is “an easily produced product of the universe” or “an insanely strange fluke, a completely weird anomalous event,” says Godfrey-Smith. Based on the current evidence, it seems that consciousness is not particularly unusual at all, but a fairly routine development in nature. “I suspect animal evolution, if were replayed again, it would produce subjectivity of a somewhat similar kind,” he adds. “You can see why it makes biological sense.” More.

Actually, the claim does not make any sense at all. Only humans have the kind of consciousness that would produce a space program.

Compared to sponges, octopuses are smart. But that does not make them anything like humans. Consciousness means only that the life form senses experiences as a unified self. Full stop. When humans are unconscious, we do not feel pain because we are not constantly assessing communications from a our unified self. We may in fact be processing previous information via dreams. What consciousness means apart from a unified self depends on the contents of the mind associated with the self. Which is why octopuses do not have a space program and humans are special.

The humans are not special claim is classic naturalist nonsense. One of the problem with science journalism today is that the pom pom wavers who practice it do not seem capable of the normal level of friendly criticism we find in other fields.

Note re non-human intelligence: We have tentatively identified some patterns. Metabolism and anatomy may play a larger role than earlier suspected. For example, reptiles can show intelligent behavior when their metabolism permits, as can invertebrates with sophisticated appendages, such as octopuses and squid.

It is even worth asking whether individual animals demonstrate more intelligence if they live with humans. For one thing, they may live much longer and in more complex environments.

Some might protest that when humans eliminate the lethal razor of natural selection, “daily and hourly scrutinizing, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest,” we cause animals to become less intelligent.

But is intelligence highly selected in nature? As engineers know all too well, new solutions to any problem are accompanied by numerous failures. The “smart crow” and “smart primate” tests, for example, are devised by humans who systematically reward the animals for carefully designed feats of intelligence, but do not destroy them for failure. Blind nature rewards and penalizes more haphazardly than that.

See also: What can we hope to learn about animal minds?

Are apes entering the Stone Age?

Furry, feathery, and finny animals speak their minds

Does intelligence depend on a specific type of brain?

and

Animal minds: In search of the minimal self