Over at The Skeptical Zone, Dr. Elizabeth Liddle has put up a post for Uncommon Descent readers, entitled, A CSI Challenge (15 May 2013). She writes:

Here is a pattern:

It’s a gray-scale image, so it is just one 2D matrix. Here is a text file containing the matrix:

I would like to know whether it has CSI or not.

The term complex specified information (or CSI) is defined by Intelligent Design advocates William Dembski and Jonathan Wells in their book, The Design of Life: Discovering Signs of Intelligence in Biological Systems (The Foundation for Thought and Ethics, Dallas, 2008), as being equivalent to specified complexity (p. 311), which is then defined as follows:

An event or object exhibits specified complexity provided that (1) the pattern to which it conforms is a highly improbable event (i.e. has high PROBABILISTIC COMPLEXITY) and (2) the pattern itself is easily described (i.e. has low DESCRIPTIVE COMPLEXITY). (2008, p. 320)

In some comments on her latest post, Dr. Liddle tells readers more about her mysterious pattern:

There are 658 x 795 pixels in the image, i.e 523,110. Each one can take one of 256 values (0:255). Not all values are represented with equal probability, though. It’s a negatively skewed distribution, with higher values more prevalent than lower…

I want CSI not FSC or any of the other alphabet soup stuff…

Feel free to guess what it is. I shan’t say for a while ☺ …

Well, if I’m understanding Dembski correctly, his claim is that we can look at any pattern, and if it is one of a small number of specified patterns out of a large total possible number of patterns with the same amount of Shannon Information, then if that proportion is smaller than the probability of getting it at least once in the history of the universe, then we can infer design…

Clearly it’s going to take a billion monkeys with pixel writers a heck of a long time before they come up with something as nice as my photo. But I’d like to compute just how long, to see if my pattern is designed…

tbh [To be honest – VJT], I think there are loads of ways of doing this, and some will give you a positive Design signal and some will not.

It all depends on p(T|H) [the probability of a specified pattern T occurring by chance, according to some chance hypothesis H – VJT] which is the thing that nobody every tells us how to calculate.

It would be interesting if someone at UD would have a go, though.

Looking at the image, I thought it bore some resemblance to contours (Chesil beach, perhaps?), but I’m probably hopelessly wrong in my guess. At any rate, I’d like to make a few short remarks.

(1) There is a vital distinction that needs to be kept in mind between a specified pattern’s being improbable as a configuration, and its being improbable as an outcome. The former does not necessarily imply the latter. If a pattern is composed of elements, then if we look at all possible arrangements or configurations of those constituent elements, it may be that only a very tiny proportion of these will contain the pattern in question. That makes it configurationally improbable. But that does not mean that the pattern is unlikely to ever arise: in other words, it would be unwarranted to infer that the appearance of the pattern in question is historically improbable, from its rarity as a possible configuration of its constituent elements.

(2) If, however, the various processes that are capable of generating the pattern in question contain no built-in biases in favor of this specified pattern arising – or more generally, no built-in biases in favor of any specified pattern arising – then we can legitimately infer that if a pattern is configurationally improbable, then its emergence over the course of time is correspondingly unlikely.

Unfortunately, the following remark by Elizabeth Liddle in her A CSI Challenge post seems to blur the distinction between configurational improbability and what Professor William Dembski and Dr. Jonathan Wells refers to in their book, The Design of Life (Foundation for Thought and Ethics, Dallas, 2008), as originational improbability (or what I prefer to call historical improbability):

Well, if I’m understanding Dembski correctly, his claim is that we can look at any pattern, and if it is one of a small number of specified patterns out of a large total possible number of patterns with the same amount of Shannon Information, then if that proportion is smaller than the probability of getting it at least once in the history of the universe, then we can infer design.

By itself, the configurational improbability of a pattern cannot tell us whether the pattern was designed. In order to assess the probability of obtaining that pattern at least once in the history of the universe, we need to look at the natural processes which are capable of generating that pattern.

(3) The “chance hypothesis” H that Professor Dembski discussed in his 2005 paper, Specification: The Pattern That Signifies Intelligence (version 1.22, 15 August 2005), was not a “pure randomness” hypothesis. In his paper, he referred to it as “the chance hypothesis most naturally associated with this probabilistic set-up” (p. 7) and later declared, “H, here, is the relevant chance hypothesis that takes into account Darwinian and other material mechanisms” (p. 18).

In a comment on Dr. Elizabeth Liddle’s post, A CSI Challenge, ID critic Professor Joe Felsenstein writes:

The interpretation that many of us made of CSI was that it was an independent assessment of whether natural processes could have produced the adaptation. And that Dembski was claiming a conservation law to show that natural processes could not produce CSI.

Even most pro-ID commenters at UD interpreted Dembski’s CSI that way. They were always claiming that CSI was something that could be independently evaluated without yet knowing what processes produced the pattern.

But now Dembski has clarified that CSI is not (and maybe never was) something you could assess independently of knowing the processes that produced the pattern. Which makes it mostly an afterthought, and not of great interest.

Professor Felsenstein is quite correct in claiming that “CSI is not … something you could assess independently of knowing the processes that produced the pattern.” However, this is old news: Professor Dembski acknowledged as much back in 2005, in his paper, Specification: The Pattern That Signifies Intelligence (version 1.22, 15 August 2005). Now, it is true that in his paper, Professor Dembski repeatedly referred to H as the chance hypothesis. But in view of his remark on page 18, that “H, here, is the relevant chance hypothesis that takes into account Darwinian and other material mechanisms,” I think it is reasonable to conclude that he was employing the word “chance” in its broad sense of “undirected,” rather than “purely random,” since Darwinian mechanisms are by definition non-random. (Note: when I say “undirected” in this post, I do not mean “lacking a telos, or built-in goal”; rather, I mean “lacking foresight, and hence not directed at any long-term goal.”)

I shall argue below that even if CSI cannot be assessed independently of knowing the processes that might have produced the pattern, it is still a useful and genuinely informative quantity, in many situations.

(4) We will definitely be unable to infer that a pattern was produced by Intelligent Design if:

(a) there is a very large(possibly infinite) number of undirected processes that might have produced the pattern;

(b) the chance of any one of these processes producing the pattern is astronomically low; and

(c) all of these processes are (roughly) equally probable.

What we then obtain is a discrete uniform distribution, which looks like this:

|

In the graph above, there are only five points, corresponding to five rival “chance hypotheses,” but what if we had 5,000 or 5,000,000 to consider, and they were all equally meritorious? In that case, our probability distribution would look more and more like this continuous uniform distribution:

|

The problem here is that taken singly, each “chance hypothesis” appears to be incapable of generating the pattern within a reasonable period of time: we’d have to wait for eons before we saw it arise. At the same time, taken together, the entire collection of “chance hypotheses” may well be perfectly capable of generating the pattern in question.

The moral of the story is that it is not enough to rule out this or that “chance hypothesis”; we have to rule out the entire ensemble of “chance hypotheses” before we can legitimately infer that a pattern is the result of Intelligent Design.

But how can we rule out all possible “chance hypotheses” for generating a pattern, when we haven’t had time to test them all? The answer is that if some “chance hypotheses” are much more probable than others, so that a few tower above all the rest, and the probabilities of the remaining chance hypotheses tend towards zero, then we may be able to estimate the probability of the entire ensemble of chance processes generating that pattern. And if this probability is so low that we would not expect to see the event realized even once in the entire history of the observable universe, then we could legitimately infer that the pattern was the product of Intelligent Design.

(5) In particular, if we suppose that the “chance hypotheses” which purport to explain how a pattern might have arisen in the absence of Intelligent Design follow a power law distribution, it is possible to rule out the entire ensemble of “chance” hypotheses as an inadequate explanation of that pattern. In the case of a power law distribution, we need only focus on the top few contenders, for reasons that will soon be readily apparent. Here’s what a discrete power law distribution looks like:

|

The graph above depicts various Zipfian distributions, which are discrete power law probability distributions. The frequency of words in the English language follows this kind of distribution; little words like “the,” “of” and “and” dominate.

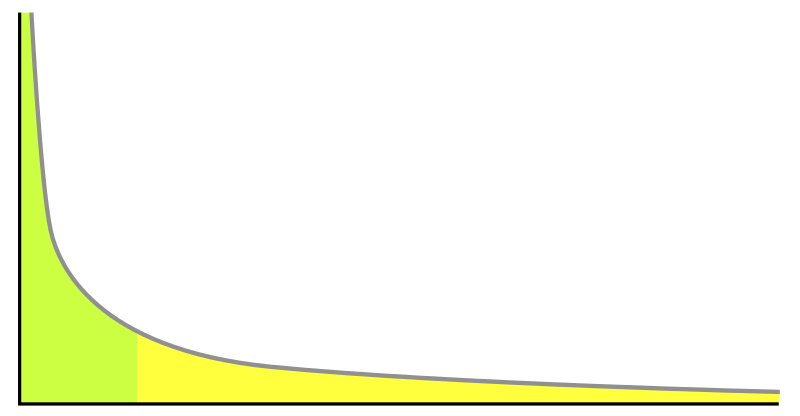

And here’s what a continuous power law distribution looks like:

|

An example of a power-law graph, being used to demonstrate ranking of popularity (e.g. of actors). To the right is the long tail of insignificant individuals (e.g. millions of largely unknown aspiring actors), and to the left are the few individuals that dominate (e.g. the top 100 Hollywood movie stars).

This phenomenon whereby a few individuals dominate the rest is also known as the 80–20 rule, or the Pareto principle. It is commonly expressed in the adage: “80% of your sales come from 20% of your clients.” Applying this principle to “chance hypotheses” for explaining a pattern in the natural sciences, we see that there’s no need to evaluate each and every chance hypothesis that might explain the pattern; we need only look at the leading contenders, and if we notice the probabilities tapering off in a way that conforms to the 80-20 rule, we can calculate the overall probability that the entire set of hypotheses is capable of explaining the pattern in question.

Is the situation I have described a rare or anomalous one? Not at all. Very often, when scientists discover some unusual pattern in Nature, and try to evaluate the likelihood of various mechanisms for generating that pattern, they find that a handful of mechanisms tend to dominate the rest.

|

The Chaos Computer Club used a model of the monolith in Arthur C. Clarke’s novel 2001, at the Hackers at Large camp site. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

(6) We can now see how the astronauts were immediately able to infer that the Monolith on the moon in the movie 2001 (based on Arthur C. Clarke’s novel) must have been designed. The monolith in the story was a black, extremely flat, non-reflective rectangular solid whose dimensions were in the precise ratio of 1 : 4 : 9 (the squares of the first three integers). The only plausible non-intelligent causes of a black monolith being on the Moon can be classified into two broad categories: exogenous (it arrived there as a result of some outside event – i.e. something falling out of the sky, such as a meteorite or asteroid) and endogenous (some process occurring on or beneath the moon’s surface generated it – e.g. lunar volcanism, or perhaps the action of wind and water in a bygone age when the moon may have had a thin atmosphere).

It doesn’t take much mental computing to see that neither process could plausibly generate a monument of such precise dimensions, in the ratio of 1 : 4 : 9. To see what Nature can generate by comparison, have a look at these red basaltic prisms from the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland:

|

In short: in situations where scientists can ascertain that there are only a few promising hypotheses for explaining a pattern in Nature, legitimate design inferences can be made.

|

The underwater formation or ruin called “The Turtle” at Yonaguni, Ryukyu islands. Photo courtesy of Masahiro Kaji and Wikipedia.

(7) We can now see why the Yonaguni Monument continues to attract such spirited controversy, with some experts, such as Masaaki Kimura of the University of the Ryukyus, who claims: “The largest structure looks like a complicated, monolithic, stepped pyramid that rises from a depth of 25 meters.” Certain features of the Monument, such as a 5 meter-wide ledge that encircles the base of the formation on three sides,

a stone column about 7 meters tall, a straight wall 10 meters long, and a triangular depression with two large holes at its edge, are often cited as unmistakable evidence of human origin. There have even been claims of mysterious writing found at the underwater site. Other experts, such as Robert Schoch, a professor of science and mathematics at Boston University, insist that the straight edges in the underwater structure are geological features. “The first time I dived there, I knew it was not artificial,” Schoch said in an interview with National Geographic. “It’s not as regular as many people claim, and the right angles and symmetry don’t add up in many places.” There is an excellent article about the Monument by Brain Dunning at Skeptoid here.

The real problem here, as I see it, is that the dimensions of the relevant features of the Yonaguni Monument haven’t yet been measured and described in a rigorously mathematical fashion. For that reason, we don’t know whether it falls closer to the “Giant’s Causeway” end of the “design spectrum,” or the “Moon Monolith” end. In the absence of a large number of man-made monuments and natural monoliths that we can compare it to, our naive and untutored reaction to the Yonaguni Monument is one of perplexity: we don’t know what to think – although I’d be inclined to bet against it’s having been designed. What we need is more information.

(8) Turning now to Dr. Elizabeth Liddle’s picture, there are three good reasons why we cannot determine how much CSI it contains.

First, Dr. Liddle is declining to tell us what the specified pattern is, for the time being. Until she does, we have no way of knowing for sure whether there is a pattern or not, short of spotting it – which might take a very long time. (Some patterns, like the Champerdowne sequence in Professor Dembski’s 2005 essay, are hard to discern. Others, like the first 100 primes, are relatively easy.)

Second, we have no idea what kind of processes were actually used by Dr. Liddle to generate the picture. We don’t even know what medium it naturally occurs in (I’m assuming here that it exists somewhere out there in the real world). Is it sand? hilly land? tree bark? We don’t know. Hence we are unable to compute P(T|H), or the probability of the pattern arising according to some chance hypothesis, as we can’t even formulate a “chance hypothesis” H in the first place.

Finally, we don’t know what other kinds of natural processes could have been used to generate the pattern (if there is one), as we don’t know what the pattern is in the first place, and we don’t know where in Nature it can be found. Hence, we are unable to formulate a set of rival “chance hypotheses,” and as a result, we have no idea what the probability distribution of the ensemble of “chance hypotheses” looks like.

In short: there are too many unknowns to calculate the CSI in Dr. Liddle’s example. A few more hints might be in order.

|

(9) In the case of proteins, on the other hand, the pattern is not mathematical (e.g. a sequence of numbers) but functional: proteins are long strings of amino acids that actually manage to fold up, and that perform some useful biological role inside the cell. Given this knowledge, scientists can formulate hypotheses regarding the most likely processes on the early Earth for assembling amino acid strings. If a few of these hypotheses stand out, scientists can safely ignore the rest. Thus the CSI in a protein should be straightforwardly computable.

I have cited the recent work of Dr. Kozulic and Dr. Douglas Axe in recent posts of mine (see here, here and here). Suffice to say that the authors’ conclusions that the proteins we find in Nature are the product of Intelligent Design is not an “Argument from Incredulity” but an argument based on solid mathematics, applied to the most plausible “chance hypotheses” for generating a protein. And to those who object that proteins might have come from some smaller replicator, I say: that’s not a mathematical “might” but a mere epistemic one (as in “There might, for all we know, be fairies”). Meanwhile, the onus is on Darwinists to find such a replicator.

(10) Finally, Professor Felsenstein’s claim in a recent post that “Dembski and Marks have not provided any new argument that shows that a Designer intervenes after the population starts to evolve” with their recent paper on the law of conservation of information, is a specious one, as it rests on a misunderstanding of Intelligent Design. I’ll say more about that in a forthcoming post.

Recommended Reading

Specification: The Pattern That Signifies Intelligence by William A. Dembski (version 1.22, 15 August 2005).

The Conservation of Information: Measuring the Cost of Successful Search by William A. Dembski (version 1.1, 6 May 2006). Also published in IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics A, Systems & Humans, 5(5) (September 2009): 1051-1061.

Conservation of Information Made Simple (28 August 2012) by William A. Dembski.

Before They’ve Even Seen Stephen Meyer’s New Book, Darwinists Waste No Time in Criticizing Darwin’s Doubt (4 April 2013) by William A. Dembski.

Does CSI enable us to detect Design? A reply to William Dembski (7 April 2013) by Joe Felsenstein at Panda’s Thumb.

NEWS FLASH: Dembski’s CSI caught in the act (14 April 2011) by kairosfocus at Uncommon Descent

Is Darwinism a better explanation of life than Intelligent Design? (14 May 2013) by Elizabeth Liddle at The Skeptical Zone.

A CSI Challenge (15 May 2013) by Elizabeth Liddle at The Skeptical Zone.