There has been a great deal of controversy recently regarding the theory of structuralism, which has been defended by Dr. Michael Denton in his new book, Evolution: Still a Theory in Crisis and attacked by Professor Larry Moran over at his Sandwalk blog (see here, here, here and here). Evolution News and Views has several articles defending Dr. Denton’s views (see here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here). Let me say at the outset that I have not yet read Dr. Denton’s latest book, which has been reviewed by Barry Arrington here. Rather than reviewing Dr. Denton’s work, my aim in today’s post is to summarize its central thesis, discuss its significance for how scientists should do biology, and evaluate what I see as the most telling criticisms of the theory of structuralism made by Professor Larry Moran, before offering a few tentative suggestions of my own as to how these criticisms might be addressed. (NOTE: Any green bolding below is my own – VJT.)

What is Structuralism?

Denton defines structuralism in his 2013 BIO-Complexity paper, The Types: A Persistent Structuralist Challenge to Darwinian Pan-Selectionism as “the concept that the basic forms of the natural world—the Types—are immanent in nature, and determined by a set of special natural biological laws, the so called ‘laws of form’.” Denton elaborates:

According to the structuralist paradigm, a significant fraction of the order of life is the result of basic physical constraints arising out of the fundamental properties of matter — more specifically biological matter. These constraints limit the way organisms are built to a few basic designs; these include the deep homologies, for example the pentadactyl limb, and the basic body plans of the major phyla. The recurring patterns and persistence of these designs implies that many of life’s basic forms arise in the same way as that of other natural forms such as crystals or atoms — from the self-organization of matter — and are thus genuine universals. Structuralists adhere therefore to a strictly “non-selectionist, non-historicist” view of the biological world…

The notion of a lawful biology, where all the major types are part of the world order no less than inorganic forms, naturally lent itself to teleological speculation. This is nowhere more apparent than in the views of Louis Agassiz, who saw the Types as ideas in the mind of God [2: ch. 4], and saw the whole taxonomic system as part of God’s grand plan of creation…

It is important to stress that structuralism therefore implies that organic order is a mix of two completely different types of order, generated by two different causal mechanisms: a primal order generated by natural law, and a secondary adaptive order imposed by environmental constraints (by natural selection according to Darwinists, by Lamarckian mechanisms and by intelligent design according to current design theorists)…

If the homologies are lawful aspects of the world order, no less than atoms or crystals, then just as for atoms or crystals, there should exist a set of laws, “Laws of Biological Form” [33: pp. 4–10; 34; 35], which would provide a rational and lawful account of the diversity of organic forms, analogous to the laws of chemistry or the laws of crystallography, which account rationally for the diversity of chemical compounds and crystals, and which allow for a rational deductive derivation of all possible chemical compounds or crystals…

The structuralist conception of life, and especially of an ascending hierarchy of taxa of ever widening comprehensiveness as an immanent feature of nature, was close to the classic Aristotelian world view [39: pp. 94–95], but it was based on the facts, not on a philosophical a priori...

…[I]n every case (to the author’s knowledge), bottom-up genetic explanations fail to account for homologous patterns, thus presenting a major challenge to the entire functionalist project, and by default providing powerful support for the alternative structuralist view — that these patterns are self-organizing emergent forms arising spontaneously from the properties of particular categories of biological matter…

…Functionalism demands preformism (a detailed blueprint specifying the final form), while structuralism implies epigenesis (emergent form based on self-organizational principles apart from any blueprint)…

…[T]he observation that is the most supportive of the structuralist claim that homologies are emergent, robust, self-organizing natural forms, is the fact that the same homologous structure may arise in different ways, involving different genes and genetic pathways in different species [98; 99]. To take a classic example, the early embryos of all vertebrates are very similar at the post-gastrula stage when the vertebrate body plan is first apparent, but the developmental processes and pathways that lead to this homologous stage differ markedly in different classes.

The real significance of Denton’s thesis

|

Portrait of English anatomist and palaeontologist Richard Owen with the skull of a crocodile. Albumen print from wet collodion on glass negative, 1856. Image courtesy of Maull & Polyblank and Wikipedia.

Denton elucidates the significance of his structuralist thesis in his post, Nature’s Dis-Continuum: Why Structural Explanations Win Hands Down. In a nutshell, if structuralism is correct, then essentialism holds true in the biological world, after all. Nature is not a continuum, as Darwinists have long maintained; rather, living things belong to clearly identifiable types. As Denton puts it:

There is no evidence to support the Darwinian claim that the biological world is a functional continuum where it is possible to move from the base of the trunk to all the most peripheral branches in tiny incremental adaptive steps.

On the contrary, all of the evidence as reviewed in the first six chapters of Evolution: Still a Theory in Crisis implies that nature is a discontinuum. The tree is a discontinuous system of distinct Types characterized by sudden and saltational transitions and sudden origins of taxa-defining novelties and homologs, exactly as I claimed in Evolution thirty years ago. The claim has weathered well!

The grand river of life that has flowed on earth over the past four billion years has not meandered slowly and steadily across some flat and featureless landscape, but tumbled constantly through a rugged landscape over endless cataracts and rapids. No matter how unfashionable, no matter how at odds with current thinking in evolutionary biology, there is no empirical evidence for believing that organic nature is any less discontinuous than the inorganic realm. There is not the slightest reason for believing that the major homologs were achieved gradually via functional continuums. It is only the a priori demands of Darwinian causation that have imposed continuity on a basically discontinuous reality.

No matter how “unacceptable,” the notion that the organic world consists of a finite set of distinct Types, which have been successively actualized during the evolutionary history of life on earth, satisfies the facts far better that its Darwinian rival.

Denton’s typological view, which is heavily influenced by the thinking of the great Victorian biologist Richard Owen (pictured above), is anathema to evolutionary biologists, whatever their stripe.

Problems with Denton’s thesis

I’ve been reading through the various posts on structuralism over at Evolution News and Views, as well as Professor Larry Moran’s posts critiquing structuralism (see here, here, here and here). In several of his posts, Moran accuses Dr. Denton of setting up a “strawman” in his characterization of the modern evolutionary view, and of “ignoring one of the most common views in evolutionary biology” – namely, that many of the structures we observe in Nature (e.g. the pentadactyl limb) are the result of historical accident, rather than natural selection. Indeed, evolutionary biologists readily admit that “the history of life is not just the product of natural selection.”

To be fair to Denton, however, it could be argued that he is not particularly concerned with what modern evolutionary biologists think, but with setting forth two rival explanations of the basic forms that we observe in living things: the structuralist view that they are embedded in organisms, and the functionalist view that they serve some adaptive purpose. Denton characterizes the functionalist view by deliberately highlighting the contrasts between it and the structuralist view. Now, if Denton wishes to delineate structuralism from functionalism in this manner, that’s perfectly valid for pedagogical purposes, so long as he does not imply that modern-day biologists regard functionalism as anything like a complete explanation of biological forms. As Professor Moran points out, they don’t, and what’s more, they haven’t done so for many decades. It is a great pity, then, that in a recent post, Denton makes a sweeping generalization about contemporary biologists which is plainly incorrect: “All Darwinists, and hence the great majority of evolutionary biologists, are functionalist by definition, as all evolution according to classical Darwinism comes about from cumulative selection to meet functional ends.” That statement is not an accurate reflection of how modern biologists explain the complex designs found in Nature.

Personally, I think that Denton would have done better to contrast structuralism with both functionalism and the “historical accident” view now espoused by a large number of biologists. In reality, what we have are three rival explanations of biological forms, rather than two. I have to say that Professor Moran makes quite a few telling arguments against structuralism in his recent posts (see above). Accordingly, I’ve put together a short list of what I see as Moran’s strongest criticisms of structuralism.

1. The theory of structuralism is too animal-centric, and cannot be applied to bacteria, which comprise the vast majority of living organisms.

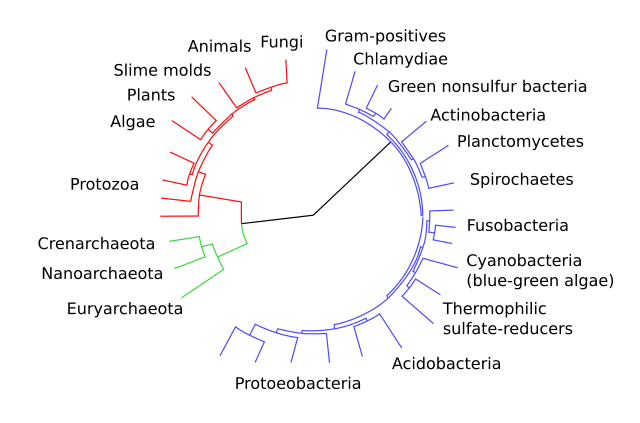

|

Animals occupy a tiny twig on the tree of life. Image courtesy of Tim Vickers and Wikipedia. Eukaryotes are colored red, archaea green and bacteria blue.

In a recent post titled, What is “structuralism”? (February 2, 2016), Professor Moran writes:

“One of the problems with structuralist explanations is that they are very animal-centric... “It’s easy to think of deterministic forms when your view is limited to vertebrates and other animals but it’s much harder to defend structuralism when you’re comparing bumblebees and mushrooms.”

Bacteria seem to be particularly recalcitrant to Michael Denton’s structuralist paradigm, since they cannot be readily classified into types or species. Microbiologists have been trying to sort them into species for over a hundred years, with little success. The discovery of lateral gene transfer in the last few decades has complicated the picture to such an extent that some biologists now propose giving up the attempt altogether. As Carl Woese and Nigel Goldenfeld (University of Urbana-Champaign, USA) put it in an oft-cited essay in Nature (“Biology’s Next Revolution,” vol. 445, 25 January 2007): “… the emerging picture of microbes as gene-swapping collectives demands a revision of such concepts as organisms, species and evolution. …. rather than discrete genomes, we see a continuum of genomic possibilities, which casts doubt on the validity of the concept of a ‘species’ when extended into the microbial realm.”

2. Denton’s structuralist theory ignores the role of chance in evolution, and fails to offer a criterion whereby we may distinguish non-adaptive structures that have arisen by pure chance from those that have arisen from “laws of form.”

|

Professor Moran proposes that the zebra’s stripes may simply be “an evolutionary accident.” Image courtesy of Muhammad Mahdi Karim and Wikipedia.

Professor Moran agrees with Denton that many biological structures are clearly non-adaptive, but suggests that instead of being the product of unknown “laws of form,” they may simply be the result of chance – an explanation he accuses Denton of deliberately overlooking in his post, Michael Denton discovers non-adaptive evolution … attributes it to gods (February 13, 2016):

Readers of this blog will know that I’m a fan of Evolution by Accident…

This is the view of many modern evolutionary biologists. Their work and views have been reported frequently on Sandwalk over the past ten years but you can find it in all the evolutionary biology textbooks…

Over the years, we’ve discussed a number of specific cases that strongly suggest non-adaptive evolution… One of my favorite examples has been the shape of leaves…

Michael Denton recognizes how silly it is to attribute every feature to adaptation. This is, of course, a view that been around for a long time among evolutionary biologists and they have perfectly naturalistic, non-adaptive, explanations that have been published in thousands of scientific papers. Denton won’t acknowledge that. Most creationists won’t even admit that there are features that don’t appear to have been designed for functionality but here’s Denton showing them that they’ve been wrong for decades…

He assures them that their extreme Darwinian view of evolution is correct and the presence of non-functional features — like the shape of a maple leaf — is something that “evolution” can’t explain. Therefore, gods did it.

Moran contends that there is no reason to believe that chance could not have generated the non-adaptive designs in Nature:

“Over the years, we’ve discussed a number of specific cases that strongly suggest non-adaptive evolution. For example, the fact that the African rhinoceros has two horns while the Asian rhino has only one [Visible Mutations and Evolution by Natural Selection], or the stripes on different species of zebra [How did the zebra get its stripes? (again)].

“One of my favorite examples has been the shape of leaves. Is the difference between a cluster of five needles (white pine) and two needles (red pine) an example of selection and adaption or an accident? What about the shape of maple leaves? There are 128 species of maple (Acer spp.) and most of them have distinctly different leaves that vary in shape, color, and size. It’s rather silly, in this day and age, to attribute all of those differences to adaptation.”

(Michael Denton discovers non-adaptive evolution … attributes it to gods, February 13, 2016.)

Are the zebra’s stripes or the shape of different species of maple the product of hidden laws, or are they the result of chance? Moran defends the latter option in a 2015 post titled, How did the zebra get its stripes? (again), where he proposes that a chance mutation may explain the origin of zebras’ stripes, and that they serve no function whatsoever:

“After almost 100 years of speculation, nobody has come up with a good adaptive explanation of zebra stripes. They never consider the possibility that there may NOT be an adaptive explanation…

“The point is that the prominence of stripes on zebras may be due to a relatively minor mutation and may be nonadaptive. That’s a view that should at least be considered even if you don’t think it’s correct.”

Denton might respond that while chance might explain some of the non-adaptive designs found in Nature, it cannot explain them all. (As we’ll see below, Denton discusses the inadequacies of chance as an explanation, in his latest book.) However, Moran contends that Denton has failed to offer a criterion whereby one might distinguish a non-adaptive structure resulting from “laws of form” from one that arose by chance.

3. The fossil record contains what appear to be ancestral species, which don’t fall neatly into modern-day body types:

|

Hyracotherium is now considered to have been ancestral not only to horses, but also to tapirs and rhinoceroses. Legend for molar tooth: dark=enamel; dotted=dentine; white=cement. Image courtesy of Mcy Jerry and Wikipedia.

In a recent post titled, Replaying life’s tape (February 11, 2016), Professor Moran approvingly quotes a passage from Stephen Jay Gould’s work, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (Belknap Press, 2002, p. 1156), in which Gould tellingly observes that ancestral forms resist classification into modern categories:

“If a group of Martian paleontologists had visited earth during the Eocene epoch, they would have encountered two coexisting, and scarcely distinguishable species of the genus Hyracotherium. If they had then followed the subsequent history of the lineages, they would have watched one species differentiate into the clade of rhinoceroses and the other into the clade of horses. But if a modern commentator then concluded that horses and rhinos had existed as distinct designs in their modern form (lithe runners vs. horned behemoths) since the Eocene, we would laugh at such a silly confusion…”

4. Many of the forms which predominate today appear to have triumphed as a result of historical accident, rather than internal necessity:

|

Kimberella quadrata, which appeared 555 million years ago, is the first bona fide fossil of a bilaterian: an animal with bilateral symmetry. Image courtesy of Aleksey Nagovitsyn, Arkhangelsk Regional Museum and Wikipedia.

In his post, Replaying life’s tape (February 11, 2016), Moran argues that the prevalence of this or that body plan in animals is largely the result of happenstance, rather than internal “laws of form.” The same goes for the genetic code found in all living things today, which is probably nothing more than a “frozen accident,” as Francis Crick hypothesized in his essay, The origin of the genetic code (Journal of Molecular Biology, 1968, 38:367-379). Finally, there’s no evidence of any built-in natural bias towards the evolution of intelligent life:

“What he [Gould – VJT] means is that just because the basic body plans of modern animals all evolved from a bilateran ancestor doesn’t mean that this pattern was preordained by the immutable laws of physics and chemistry. It could be an accident of history that was locked in by constraints on subsequent evolution (historical contingency) just as the genetic code may have been a ‘frozen accident.’…

“The point here is that the concept of unpredictability in the history of life is based not on wild speculation but on solid evidence from the fossil record and computer simulations and a firm understanding of modern evolutionary theory and history.

“If you replay the tape of life there’s a good chance that no intelligent life will evolve. There’s no evidence that the actual history was pre-determined by any fundamental laws of form and there’s certainly no evidence of purpose.”

(Replaying life’s tape, February 11, 2016.)

5. In any case, there’s nothing wrong with an explanation which appeals to contingent past events, as opposed to internal necessity:

|

Ichthyostega, which appeared around 365 million years ago, had seven digits on each hind limb, while Acanthostega has eight. In his widely cited essay, Eight (or Fewer) Little Piggies, Stephen Jay Gould describes the tetrapod species of the Devonian period and concludes: “Five is not a canonical, or archetypal, number of digits for tetrapods–at least not in the primary sense of ‘present from the beginning.'” Pencil drawing, digital coloring, based on a reconstruction by Ahlberg, 2005. Image courtesy of Nobu Tamura and Wikipedia.

In his post, Replaying life’s tape (February 11, 2016), Professor Larry Moran warmly endorses Stephen Jay Gould’s argument (made in his essay, Eight (or Fewer) Little Piggies) that an explanation which appeals to contingent past events is not one whit inferior to an explanation which invokes laws of nature:

“Never apologize for an explanation that is “only” contingent and not ordained by invariant laws of nature — for contingent events have made our world and our lives. If you ever feel the slightest pull in that dubious direction, think of poor Heathcliff, who would have been spared so much agony if only he had stayed a few more minutes to eavesdrop upon the conversation of Catherine and Nelly (yes, the book wouldn’t have been as good, but consider the poor man’s soul). Think of Bill Buckner who would never again let Mookie Wilson’s easy grounder go through his legs–if only he could have another chance. Think of the alternative descendants of Ichthyostega, with only four fingers on each hand. Think of arithmetic with base eight, the difficulty of playing triple fugues on the piano, and the conversion of this essay into an illegible Roman tombstone, for how could I separate words withoutathumbtopressthespacebaronthistypewriter.”

In a nutshell, Gould’s (and Moran’s) contention is that the urge to explain biological forms in terms of laws reflects a psychological bias on our part: a preference for necessity over contingency.

My response to Moran’s criticisms

I won’t presume to second-guess what Dr. Michael Denton would say in response to Professor Moran’s criticisms. At any rate, here’s how I would respond, if I were a structuralist:

1. How does structuralism account for bacteria?

If Denton is right, then it should be possible to classify bacteria fairly readily, in a natural fashion, on the basis of their structures, without considering their functions, their genes or their ancestry. But which structures? If Denton is right, then it should be possible to construct a taxonomy of bacteria, based purely on the different proteins and lipids they contain. In his 2013 BIO-Complexity paper, The Types: A Persistent Structuralist Challenge to Darwinian Pan-Selectionism, Denton argues that proteins are bound by the same laws of form that govern structures such as the pentadactyl limb:

Protein folds represent one of the most remarkable cases where a set of physical rules determine the forms of an important class of complex molecular structures [35; 62; 63]. Intriguingly, the rules that generate the thousand-plus known protein folds have now been largely elucidated and remarkably they amount to a set of ‘laws of form’ of precisely the kind sought after by early 19th-century biologists (see above). These rules arise from higher-order packing constraints of alpha helices and beta sheets, and constrain possible protein forms to a small number of a few thousand structures [64]. In conformity with pre-Darwinian structuralism, the protein forms are analogous to a set of crystals [35]!

In the same paper, Denton adds that “[l]ipid membranes form a vast variety of tubes and vesicles, and various types of sheets” and he adds that in the case of lipids, “there is no doubt that the underlying form—layered stacks of bilayer lipid membranes—is primarily determined by purely physical law.”

While we’re on the subject of taxonomy, I should point out that there is no reason why the taxonomies produced by a structuralist analysis should match evolutionary trees. To take one instance: the Victorian biologist Richard Owen famously classified vertebrates into five classes (fish, amphibia, reptiles, birds and mammals) on anatomical grounds, but a cladist would say that all tetrapods are merely an off-shoot of fish, and that a mammal is more like a bony fish than a shark is. Common sense sides with Owen. The cladists are wrong; they simply don’t understand what true similarity really means.

2. How do we distinguish forms that have arisen by chance from those that have arisen from “laws of form”?

One way of distinguishing structures that have arisen by chance from those that have arisen from laws of form is to investigate how easily these structures can be modified. If the structures resist modification and revert to type, then it would appear that we are dealing with something deeply entrenched. Dr. Denton hints at this response in his 2013 BIO-Complexity paper, The Types: A Persistent Structuralist Challenge to Darwinian Pan-Selectionism:

In addition to their remarkable abstract character, the other striking feature of the homologies is their great stability through millions of generations and in diverse phylogenetic lines. The pentadactyl limb, for example (see Figure 1), first emerged some 400 million years ago and has remained essentially invariant in all tetrapod lines ever since… The ‘concentric whorl plan’ of the Angiosperm flower has remained unchanged at least in the higher eudicot clade for 100 million years, since the late Cretaceous. The defining features of insects and even of the various insect subgroups such as the ants have also remained constant for millions of generations [29]. The abstract nature and deep invariance of the homologies and the Types is a fact, a simple straightforward biological fact.

As we have seen, Professor Moran accuses Denton of neglecting to consider the view that complex non-adaptive designs may be the result of chance, rather than laws of form. But as Dr. Ann Gauger points out in an ENV post titled, Reading Michael Denton’s Mind…and Getting It Wrong (February 18, 2016), Denton considers and rejects such a view in his book, Evolution: Still a Theory in Crisis:

The complexity of living systems is so great that there is now an almost universal consensus, as we saw in the discussion of ORFan genes, that the simplest of all biological novelties — a single functional gene sequence — cannot come about by chance mutations in a DNA sequence. And if an individual gene sequence is far too complex to be produced by chance, then the sudden origination of a morphological novelty like a feather, a limb, or even such a comparatively simple novelty as an enucleate red cell — all novelties vastly more complex than an individual functional gene sequence — is by any common-sense judgment far beyond the reach of any sort of undirected “chance” saltation.” [p. 226]

This is all well and good, but what about zebras’ stripes and the various shapes of maple leaves? Does Denton really wish to argue that these forms are beyond the reach of chance? Frankly, I doubt it.

I might add that even Denton’s contention that de novo genes could not have arisen by chance is highly controversial. As a rule, these genes tend to be very short, and they produce small proteins (75 aa or less) rather than the long-chain proteins found in all living things, which Dr. Douglas Axe has shown to be beyond the reach of chance. (Incidentally, there’s a very good article on the origin of the genes required for the appearance of feathers here: it seems to have occurred in two bursts, spaced over 100 million years apart.)

In short: Denton needs to engage in mathematical reasoning, if he wishes to clearly differentiate the biological forms that could be due to chance from those that could not.

3. What about ancestral forms that don’t neatly fall into modern-day categories?

Ancestral species are poorly preserved: all too often, we have only their hard parts (bones), which means that it is not always easy to tell which “body type” they belong to, as other distinguishing organs have not been preserved. Presumably, if we had more information, we could make such a determination more readily. We also need to bear in mind that ancestral forms may be hard to classify, simply because they pre-date the “types” that they subsequently gave rise to.

To take Gould’s example: Hyracotherium may defy easy categorization as a member of either the horse, tapir or rhinoceros “kind,” but nobody would mistake Mesohippus for an ancestor of the rhinoceros or tapir: it is unambiguously in the equine lineage, while Merychippus can be considered a “true horse.” I might add that while modern-day “types” are distinguished by several complex structures that they alone possess, there is nothing in Denton’s theory which requires that all of these distinguishing features had to have originated at the same time. Consequently, we should not be at all surprised if horses dating from the Oligocene epoch are considerably less “horsey” in their anatomical features than their modern-day descendants.

4. Don’t accidents in the history of life on Earth undermine structuralism?

Historical accidents (such as the Permian extinction) may decide which biological structures will eventually prevail in the history of life, but they cannot be successfully urged as an argument against the existence of structures per se. In any case, such extinction events may do no more than hasten a trend which was already in progress. It may have been an asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs (excluding birds), but according to some paleontologists, they would have eventually died out, anyway, and been replaced by other, more intelligent creatures.

5. Doesn’t the fossil record show that some forms triumphed by accident?

The case of the fossil amphibian Ichthyostega and its seven fingers is still a mystery, chiefly because scientists still don’t know why mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians all develop five fingers during their embryological development. For an up-to-date summary of what scientists currently know, I’d recommend Ed Yong’s highly informative article, How did you get five fingers?

In short: more work needs to be done. Also, we don’t know whether the seven-finger pattern would have been viable over the long term, in any case.

Unresolved tensions within Denton’s structuralist position

In his 2013 BIO-Complexity paper, The Types: A Persistent Structuralist Challenge to Darwinian Pan-Selectionism, Denton defends the view that life’s basic designs are the product of laws of form, and that they are immanent in the world-order. If this view is correct, then these designs are the product of necessity, rather than contingency. At the same time, Denton wishes to argue that structuralism is fully compatible with Intelligent Design, and that the forms we find in Nature may have been chosen by the Creator for aesthetic reasons. But a choice, by definition, is contingent, whereas a law is necessary. “Laws of form” is an explanation of complexity that might appeal to an atheistic naturalist; creative choices, on the other hand, require a purposeful Agent.

The foregoing difficulty could be surmounted by pointing out that the laws of Nature are necessary only in a relative sense: as creatures, we are bound by them, but in an absolute sense, there is no reason why the universe we live in has to conform to these laws, rather than those laws. The fact that we live in a universe whose laws favor life still requires an explanation, and positing that the laws of Nature are the result of elegant fine-tuning of the laws of Nature by an all-wise Creator is the most rational explanation that we know of. (The “multiverse” fails as an explanation, for reasons I have discussed here.)

Even so, Denton’s claims about “laws of form” still runs counter to the arguments advanced by Dr. Stephen Meyer in his Book, Signature in the Cell, which argues on biochemical grounds that there are no “laws of form” that dictate the emergence of proteins – which is why the emergence of even one long-chain protein on the primordial Earth (let alone the 250-odd proteins required for a minimal cell) would have been tantamount to a miracle, requiring an Intelligent Agent to explain its occurrence.

Perhaps Denton could reply that these “laws of form” are higher-level laws, built into the nature of matter by an all-wise Creator. That may be so, but such a claim still requires evidence.

I would be remiss if I did not mention another difficulty with the notion that laws generate complex structures, pointed out many years ago by biochemist and Intelligent Design proponent, Professor Michael Behe, who remarked in a 1999 review of Paul Davies’ book, The Fifth Miracle: The Search for the Origin and Meaning of Life, that laws are low in information, while life is high in information. As Behe puts it: “laws cannot contain the recipe for life because laws are ‘information-poor’ while life is ‘information-rich.'”

Physicist David Snoke echoes this criticism in a laudatory review of Denton’s book, where he faults Denton’s theory of the origin of complex forms for its materialism – for although Denton’s structuralist theory sounds a lot like neo-Platonism, Denton insists that his theory of the origin of forms invokes purely physical processes:

Denton favors some version of “self-organization” along the lines promoted by Ilya Prigogene and Stuart Kaufmann. Somehow, internal physical forces conspire to create something completely new… …I am familiar with the physics of self-organization and pattern formation, and can say that despite the grand claims made for it, that line of research is nearly dead, and hopeless as a way of generating life…. Spontaneous pattern formation works for regular patterns like crystals and waves, but simply can’t carry the freight of generating the vast amounts of specified information in living organisms.

In his review, Snoke suggests that the variety of complex structures found in living things today may have been “pre-programmed in the very first living organism” – an intriguing proposal, but one which invites the question of how the information generating these structures was preserved over a four-billion-year period, long before these structures had even appeared on Earth.

Finally, a European philosopher whom I know points out some additional problems with Denton’s theory. First, Denton claims that the process whereby forms arise in Nature must be a saltationist one, but he never explains how the “laws of form” can generate the necessary leaps.

Second, Denton’s theory explains the emergence of shapes and geometrical structures, rather than the underlying Aristotelian forms which explain why these types of organisms have the propensities that they do. From an Aristotelian perspective, structuralism digs deeper than Darwinism, but still not deep enough. It does not fully explain the “types” we find in Nature.

For these reasons, my reaction to Denton’s structuralist theory is very much a “wait and see” reaction. It may yet prove itself, but we need to give it time. The theory undoubtedly contains some rich and deep insights, and its resurrection of essentialism will certainly be heartening for Intelligent Design proponents.

At this point, I shall stop and throw the discussion open to my readers. What do you think of Denton’s theory?