|

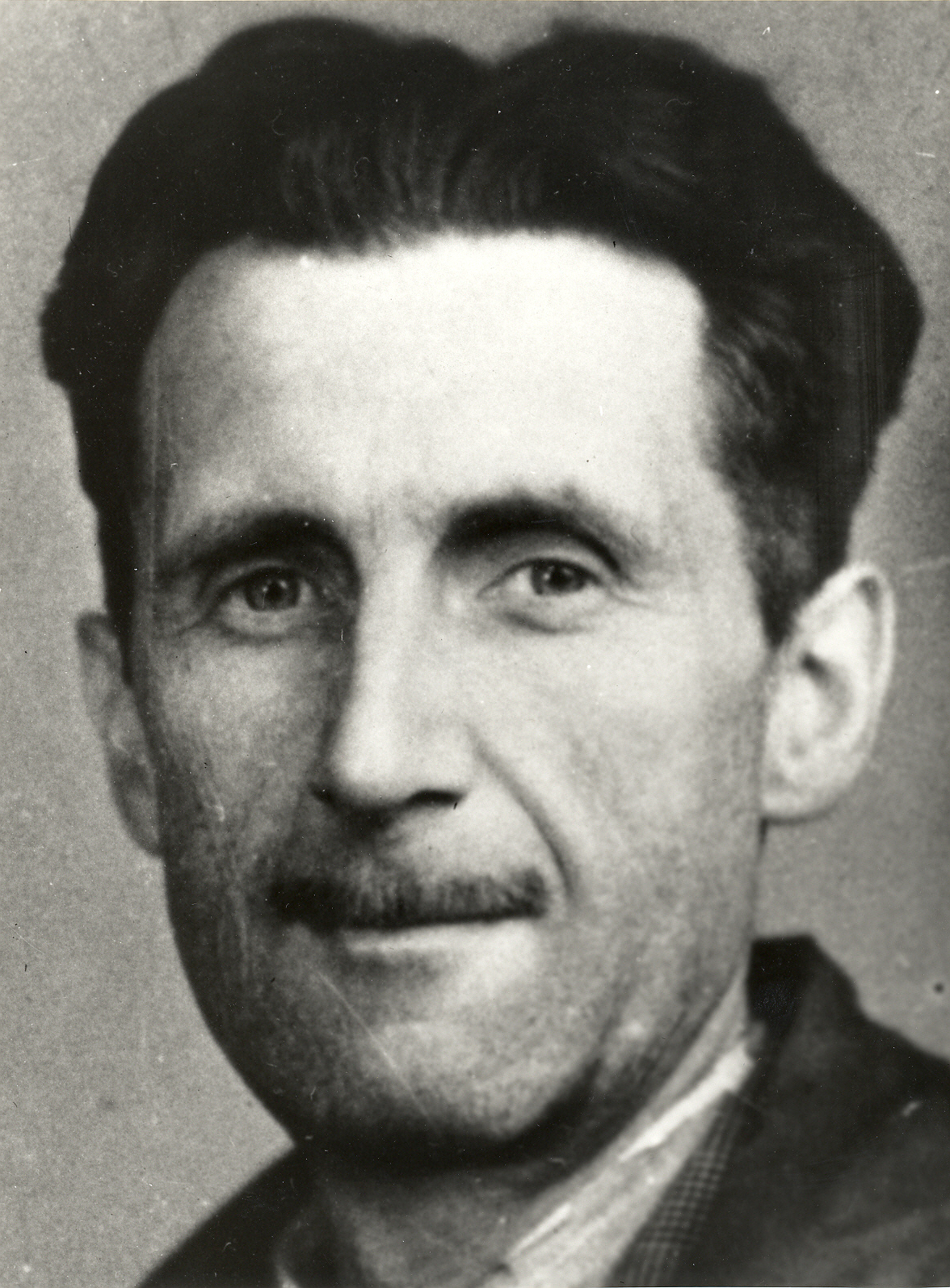

Recently, while browsing through the essays of George Orwell – a writer I’ve always admired, even when I disagree with him – I came across one entitled, What is Science? which struck me as both timely and prescient. I’d like to quote a few excerpts, and invite readers to weigh in with their opinions. (Emphases below are mine.)

…[T]he word Science is at present used in at least two meanings, and the whole question of scientific education is obscured by the current tendency to dodge from one meaning to the other.

Science is generally taken as meaning either (a) the exact sciences, such as chemistry, physics, etc., or (b) a method of thought which obtains verifiable results by reasoning logically from observed fact.

If you ask any scientist, or indeed almost any educated person, “What is Science?” you are likely to get an answer approximating to (b). In everyday life, however, both in speaking and in writing, when people say “Science” they mean (a). Science means something that happens in a laboratory: the very word calls up a picture of graphs, test-tubes, balances, Bunsen burners, microscopes. A biologist, and astronomer, perhaps a psychologist or a mathematician is described as a “man of Science”: no one would think of applying this term to a statesman, a poet, a journalist or even a philosopher. And those who tell us that the young must be scientifically educated mean, almost invariably, that they should be taught more about radioactivity, or the stars, or the physiology or their own bodies, rather than that they should be taught to think more exactly.

Orwell is arguing here that science, in the true sense of the word, is about forming one’s opinions by thinking clearly about facts that are publicly shareable and demonstrable. On this definition, anyone who has acquired the habit of thinking in this way should be entitled to call themselves a scientist.

In Orwell’s day, it was seen as a Good Thing that students should learn about “radioactivity, or the stars, or the physiology or their own bodies”; nowadays, educating our young about Darwinian evolution, sexual health for kindergartners, and global warming is deemed to be the latest Good Thing. The focus has changed; but sadly, the paternalistic mindset of the “powers that be” hasn’t.

The demand for more science education, as Orwell astutely perceived, reflects an underlying political agenda, based on the naive belief – falsified by history – that we’d all be better off if scientists ruled the world:

This confusion of meaning, which is partly deliberate, has in it a great danger. Implied in the demand for more scientific education is the claim that if one has been scientifically trained one’s approach to all subjects will be more intelligent than if one had had no such training. A scientist’s political opinions, it is assumed, his opinions on sociological questions, on morals, on philosophy, perhaps even on the arts, will be more valuable than those of a layman. The world, in other words, would be a better place if the scientists were in control of it. But a “scientist”, as we have just seen, means in practice a specialist in one of the exact sciences. It follows that a chemist or a physicist, as such, is politically more intelligent than a poet or a lawyer, as such. And, in fact, there are already millions of people who do believe this.

But is it really true that a “scientist”, in this narrower sense, is any likelier than other people to approach non-scientific problems in an objective way? There is not much reason for thinking so. Take one simple test – the ability to withstand nationalism. It is often loosely said that “Science is international”, but in practice the scientific workers of all countries line up behind their own governments with fewer scruples than are felt by the writers and the artists. The German scientific community, as a whole, made no resistance to Hitler. Hitler may have ruined the long-term prospects of German Science, but there were still plenty of gifted men to do the necessary research on such things as synthetic oil, jet planes, rocket projectiles and the atomic bomb. Without them the German war machine could never have been built up… More sinister than this, a number of German scientists swallowed the monstrosity of “racial Science”. You can find some of the statements to which they set their names in Professor Brady’s The Spirit and Structure of German Fascism.

Orwell goes on to praise science as “a rational, sceptical, experimental habit of mind” and as “a method that can be used on any problem that one meets.” Orwell’s inclusive phrase, “any problem that one meets,” may at first sight suggest that he viewed science as the only road to truth, but he isn’t saying that. In endorsing science – defined in the broad sense – as a method of solving any and every problem, Orwell is not declaring that science alone can give us knowledge, or that science alone can lead us to truth – conclusions that would only follow if the set of truths that can be known coincided with the set of problems that can be solved.

Orwell concludes by suggesting that what young people really need to be taught is not lots of scientific facts, but critical thinking, and rhetorically asking what will happen to the prestige hitherto enjoyed by scientists, and to their claim to be wiser than the rest of us?

But does all this mean that the general public should not be more scientifically educated? On the contrary! All it means is that scientific education for the masses will do little good, and probably a lot of harm, if it simply boils down to more physics, more chemistry, more biology, etc., to the detriment of literature and history. Its probable effect on the average human being would be to narrow the range of his thoughts and make him more than ever contemptuous of such knowledge as he did not possess: and his political reactions would probably be somewhat less intelligent than those of an illiterate peasant who retained a few historical memories and a fairly sound aesthetic sense.

Clearly, scientific education ought to mean the implanting of a rational, sceptical, experimental habit of mind. It ought to mean acquiring a method – a method that can be used on any problem that one meets – and not simply piling up a lot of facts. Put it in those words, and the apologist of scientific education will usually agree. Press him further, ask him to particularise, and somehow it always turns out that scientific education means more attention to the sciences, in other words – more facts. The idea that Science means a way of looking at the world, and not simply a body of knowledge, is in practice strongly resisted. I think sheer professional jealousy is part of the reason for this. For if Science is simply a method or an attitude, so that anyone whose thought-processes are sufficiently rational can in some sense be described as a scientist – what then becomes of the enormous prestige now enjoyed by the chemist, the physicist, etc. and his claim to be somehow wiser than the rest of us?

What, indeed? Remember that, the next time someone asks you to believe in Darwinian evolution, or in the fixity of each person’s “sexuality” (whatever that woolly term means), or in dangerous anthropogenic global warming (as opposed to a modest rise of 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100), based on the “overwhelming consensus” of scientists in the field.

Readers might also like to have a look at Barry Arrington’s 2010 post, Expert, Smexpert, which addresses the question of when it’s rational NOT to believe an expert.

Was Orwell right about science? What do readers think?