|

|

Professor Jerry Coyne has written an op-ed piece for USA Today entitled, Why you don’t really have free will. The kind of free will that Professor Coyne is concerned with is the kind that ordinary people believe in: “If you were put in the same position twice — if the tape of your life could be rewound to the exact moment when you made a decision, with every circumstance leading up to that moment the same and all the molecules in the universe aligned in the same way — you could have chosen differently.” Coyne is adamant that any lesser kind of freedom is not worth having:

As Sam Harris noted in his book Free Will, all the attempts to harmonize the determinism of physics with a freedom of choice boil down to the claim that “a puppet is free so long as he loves his strings.”

In other words, Coyne is an incompatibilist: he thinks that determinism is incompatible with the existence of free will. Here I agree with him, for reasons which I have discussed in a previous post. Professor Coyne’s contra-causal definition of free will also sounds fairly sensible to me: if freedom means anything at all, it surely means that we could have done otherwise than what we did, when we made our choices.

Unlike Professor Coyne, I firmly believe in free will – and by that, I mean the libertarian variety. In this post, I intend to argue that the scientific arguments which Coyne marshals against free will are deficient. I will also contend that in order for the proper scientific investigation of free will to proceed, the issue of free will needs to be divorced from the philosophical question of whether our voluntary acts are performed by an immaterial soul or by the brain. A materialist can consistently believe in libertarian free will, as did President Thomas Jefferson, who conceived of thought as an action of matter. In this post, I’ll endeavor to explain how free will might work, and I’ll advance a tentative account which is compatible with (but does not require) materialism.

I would like to state for the record that I am not a materialist, for reasons that I’ve explained here. However, my arguments against materialism are based not on the nature of the will as such, but on the actions of the human intellect: they purport to show that it is impossible in principle for the operations of the intellect to be explained in a materialistic way. If these arguments turn out to be invalid, then one could still consistently hold that free will resides in the brain, and not in an immaterial soul.

Does physics rule out free will?

Without further ado, let’s have a look at Professor Coyne’s arguments against free will. Surprisingly, there are only two. One argument is based on the laws of physics:

The first is simple: we are biological creatures, collections of molecules that must obey the laws of physics. All the success of science rests on the regularity of those laws, which determine the behavior of every molecule in the universe. Those molecules, of course, also make up your brain – the organ that does the “choosing.”

What Coyne is arguing here is that modern science presupposes determinism, which is incompatible with libertarian free will. But one can believe in the reality of laws of physics without believing that they determine the behavior of particles. Laws may merely constrain particles’ behavior, which is another matter entirely.

I also find it strange that proponents of determinism, when they put forward this argument, seldom tell us exactly which laws of physics imply the truth of determinism. The law of the conservation of mass-energy certainly doesn’t; and neither does the law of the conservation of momentum. Newtonian mechanics is popularly believed to imply determinism, but this belief was exploded over two decades ago by John Earman (A Primer on Determinism, 1986, Dordrecht: Reidel, chapter III). In 2006, Dr. John Norton put forward a simple illustration which is designed to show that violations of determinism can arise very easily in a system governed by Newtonian physics (The Dome: An Unexpectedly Simple Failure of Determinism. 2006 Philosophy of Science Association 20th Biennial Meeting (Vancouver), PSA 2006 Symposia.) In Norton’s example, a mass sits on a dome in a gravitational field. After remaining unchanged for an arbitrary time, it spontaneously moves in an arbitrary direction. The mass’s indeterministic motion is clearly incompatible with Newtonian mechanics. Norton describes his example as an exceptional case of indeterminism arising in a Newtonian system with a finite number of degrees of freedom. (On the other hand, indeterminism is generic for Newtonian systems with infinitely many degrees of freedom.)

Sometimes the Principle of Least Action is said to imply determinism. But since the wording of the principle shows that it only applies to systems in which total mechanical energy (kinetic energy plus potential energy) is conserved, and as it deals with the trajectory of particles in motion, I fail to see how it would apply to collisions between particles, in which mechanical energy is not necessarily conserved. At best, it seems that the universe is fully deterministic only if particles behave like perfectly elastic billiard balls – which is only true in an artificially simplified version of the cosmos. Perhaps I’m wrong here – but if I am, then I think it’s about time the proponents of determinism made their case more clearly, instead of resorting to vague appeals to “science.”

Does quantum indeterminacy have any implications for free will?

I haven’t even mentioned quantum indeterminacy so far. The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle has been interpreted by many scientists as implying that determinism does not hold at the sub-microscopic level (although I should mention that there are perfectly consistent deterministic interpretations of quantum mechanics). In recent decades, a number of philosophers and scientists have suggested that the workings of the human brain may not be deterministic either, leaving the door open to some kind of freedom. However, the reaction to this proposal from most scientists has been negative: the physicist Max Planck argued that if it were true, then “the logical result would be to reduce the human will to an organ which would be subject to the sway of mere blind chance” – and hence, not free.

But Planck’s response is flawed on two counts. First, all it shows is that quantum indeterminacy is not a sufficient condition for human freedom. The question we are addressing here, however, is whether it could be a necessary condition.

Second, Planck’s response implicitly assumes that a non-deterministic system is “subject to the sway of mere blind chance” – and nothing else. However, it is easy to show that a non-deterministic system may be subject to specific constraints, while still remaining random. These constraints may be imposed externally, or alternatively, they may be imposed from above, as in top-down causation. To see how this might work, suppose that my brain performs the high-level act of making a choice, and that this act imposes a constraint on the quantum micro-states of tiny particles in my brain. This doesn’t violate quantum randomness, because a selection can be non-random at the macro level, but random at the micro level. The following two rows of digits will serve to illustrate my point.

1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1

0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1

The above two rows of digits were created by a random number generator. The digits in some of these columns add up to 0; some add up to 1; and some add up to 2.

Now suppose that I impose the non-random macro requirement: keep the columns whose sum equals 1, and discard the rest. I now have:

1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1

0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0

Each row is still random (at the micro level), but I have now imposed a non-random macro-level constraint on the system as a whole (at the macro level). That, I would suggest, what happens when I make a choice.

Top-down causation and free will

What I am proposing, in brief, is that top-down (macro–>micro) causation is real and fundamental (i.e. irreducible to lower-level acts). For if causation is always bottom-up (micro–>macro) and never top-down, or alternatively, if top-down causation is real, but only happens because it has already been determined by some preceding occurrence of bottom-up causation, then our actions are simply the product of our body chemistry – in which case they are not free, since they are determined by external circumstances which lie beyond our control. But if top-down causation is real and fundamental, then a person’s free choices, which are macroscopic events that occur in the brain at the highest level, can constrain events in the brain occurring at a lower, sub-microscopic level, and these constraints then can give rise to neuro-muscular movements, which occur in accordance with that person’s will. (For instance, in the case I discussed above, relating to rows of ones and zeroes, the requirement that the columns must add up to 1 might result in to the neuro-muscular act of raising my left arm, while the requirement that they add up to 2 might result in to the act of raising my right arm.)

Thus we can mount a good defense of human freedom by hypothesizing that human choices (which are holistic acts that are properly ascribed to persons) are capable of influencing lower-level events in the human body, such as activities taking place in nerve cells when they process incoming signals. Additionally, we may hypothesize that the operation of nerve cells is not always deterministic, or even deterministic most of the time with occasional random disturbances, but that fundamental, higher-level actions occurring in the brain (i.e. human choices) can constrain the microscopic behavior of nerve cells, and that these constraints, when aggregated over a large number of nerve cells, can result in neuro-muscular movements.

Readers will notice that in the foregoing account, I have said nothing about an immaterial soul. For my own part, I happen to believe in one, as I see no way in which a bodily process of any kind – whether high-level or low-level – can be said to possess meaning in its own right, as our beliefs and desires clearly do. I conclude that a thought cannot be identified with any kind of bodily process, and that a volition which is based on that thought cannot be equated with any physical process either. If I’m right, then we have to embrace some kind of dualism, as I proposed in a post entitled, Why I think the Interaction Problem is Real. But if this philosophical argument for the immateriality of the human intellect turns out to be mistaken, then we will simply have to say, as the philosopher John Locke did, that it is possible for “matter fitly disposed” to think and choose, after all – an assertion which scandalized some of his contemporaries, but which is held by some Christians (e.g. Jehovah’s Witnesses).

Do laboratory experiments rule out the existence of free will?

Professor Coyne’s second argument against human freedom is an experimental one: our choices are predictable, several seconds before we consciously make them:

Recent experiments involving brain scans show that when a subject “decides” to push a button on the left or right side of a computer, the choice can be predicted by brain activity at least seven seconds before the subject is consciously aware of having made it.

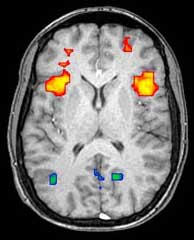

Well, let’s have a look at these experiments, shall we? The following video of a “No free will” experiment by John-Dylan Haynes (Professor at the Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience Berlin), appears to refute the notion of free will. According to the video, an outside observer, monitoring my brain, can tell which of two buttons I’m going to push, six seconds before I consciously decide to do so. But there are several things about this experiment that Professor Coyne left out of his op-ed piece.

Unimpressive results

First, as Coyne acknowledges in a post on his Web site, Why Evolution Is True, entitled, The no-free-will experiment, avec video, “the ‘predictability’ of the results is not perfect: it seems to be around 60%, better than random prediction but nevertheless statistically significant.” Sorry, but I don’t think that’s very impressive. What we have here is the simplest of all possible choices – “Press the button in your left hand or the button in your right hand” – being monitored by an MRI scanner, while a trained professional is looking on. If the outside observer guessed the subject’s choice, he’d be right 50% of the time; with the aid of an MRI scanner, the accuracy rises to 60%. This is the experiment that’s supposed to shatter my belief in free will? I’m absolutely devastated.

Adina Roskies, a neuroscientist and philosopher who works on free will at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, isn’t too impressed with Professor Haynes’ experiment either. “All it suggests,” she says, “is that there are some physical factors that influence decision-making”, which shouldn’t be surprising. That’s quite different from claiming that you can see the brain making its mind up before it is consciously aware of doing so.

Reflection was ruled out at the start

Second, the experiment was deliberately designed to exclude the possibility of reflection. In the experiment, as narrator Marcus du Sautoy (Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford) puts it, “I have to randomly decide, and then immediately press, one of these left or right buttons.” Now, most people would say that a reflective weighing up of options is integral to the notion of free will. There is a philosophical difference between liberty of spontaneity – as exemplified by the phrase, “free as a bird” – and liberty of choice, which is peculiar to rational animals like ourselves. Acting on impulse is not the same as making a free decision.

The choice was artificial, in several ways

Third, the experiment relates to an artificial choice which is stripped of several features which normally characterize our free choices:

(a) it’s completely arbitrary. It doesn’t matter which button the subject decides to press. Typically, our choices are about things that really do matter – e.g. who the next President of the United States will be.

(b) it’s binary: left or right. In real life, however, we usually choose between multiple options – often, between an indefinitely large number of options – for example, when we ask ourselves, “What career shall I pursue after I graduate?”

(c) it’s zero-dimensional. Normally, when we make choices, there are multiple axes along which we can evaluate the desirability of the various options – e.g. when deciding which city to move to, we might consider factors such as weather, proximity of family members and income earning opportunities. One city might have ideal weather but few job opportunities; another may be close to where family members live, but bitterly cold. In the experiment described above, there were no axes along which we could weigh up the desirability of the two options (left or right button), as there was literally nothing to compare.

(d) it’s impersonal. We are social animals, and most of our choices relate to other people – e.g. “Whom shall I marry?” Pressing a button, on the other hand, is a solitary act.

(e) it contains no reference to second-order mental states. Typically, when we choose, we give careful consideration to what other people will think of our choice, and how they’ll feel about it – e.g. “What will people think if I wear a clown suit on Casual Friday, and will my boss be annoyed?” To entertain these thoughts, we have to be capable of second-order mental states: thoughts about other people’s thoughts. These are a vital part of what makes us human: although chimps certainly know what other individuals want, there’s no good evidence to date that chimps have beliefs about other individuals’ beliefs. Humans may be unique in having what psychologists refer to as a theory of mind.

(f) it’s future-blind. The choice of whether to press the left button or the right button is a here-and-now choice, with no reference to future consequences. In real life, choices are seldom divorced from consequences, and we fail to advert to these consequences at our peril. For example, choosing to party the night before an exam may ruin your career prospects forever.

(g) it has no feedback mechanism. Not only do choices typically have consequences, but the results of our choices are usually communicated back to us in a way that influences our future behavior. Think of the experience of learning to ride a bicycle, when you were a child. And now compare this with the button-pressing example: no feedback, nothing learned by the subject.

So, what can the predictability (60% of the time) of an arbitrary, binary, impersonal choice, which involves no weighing up, no worries about what other people might think, no thought of the future and no feedback, possibly tell us about the existence of free will in human beings? Absolutely nothing.

What about “free won’t”?

Fourth, the experiment described by Coyne made no attempt to evaluate Benjamin Libet’s hypothesis of “free won’t”: “while we may not be able to choose our actions, we can choose to veto our actions.” What happens if the subject is permitted to decide in advance which button they will press, but is also free to change their mind at the last minute? Can a trained outside observer, who is monitoring an MRI scanner, pick up this sudden change of mind on the subject’s part? Coyne does not tell us. He writes that “from the standpoint of physics, instigating an action is no different from vetoing one, and in fact involves the same regions of the brain.” Fine; but that does not tell us whether a veto is in fact predictable in advance. Only experiments can demonstrate whether this is true or not.

Can free will be meaningfully attributed to acts performed over a short time period?

A fifth criticism that can be made of Haynes’ experiment is that the time scale involved makes it meaningless to speak of free will or its absence, just as it would be meaningless to ask what color a hydrogen atom is. Typically, our free choices are preceded by an extended period of deliberation, followed by the brain’s preparation for the execution of a bodily movement, followed by activation of specialized areas of the brain which are responsible for the contraction of specific muscles in the body. It could therefore be argued that freedom is a property which does not attach to the decision to act here and now, but to the entire process leading up to the decision. If this criticism is correct, then those who argue against free will based on experiments like the one recently conducted by Professor Haynes, are simply making a category mistake.

Do magnetic fields interfere with free will?

Finally, we need to consider the possibility that magnetic fields themselves may actually interfere with the exercise of free choice, which would invalidate the experiment described by Coyne. After all, scientists have already shown that they can alter people’s moral judgments simply by disrupting a specific area of the brain with magnetic pulses (Liane Young et al. “Disruption of the right temporoparietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgments.” In PNAS April 13, 2010 vol. 107 no. 15, 6753-6758, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914826107). In another experiment, researchers found that it was possible to influence which hand people move by stimulating frontal regions that are involved in movement planning using transcranial magnetic stimulation in either the left or right hemisphere of the brain. Curiously, the subjects continued to report that they believed their choice of hand had been made freely. (Ammon, K. and Gandevia, S.C. (1990) “Transcranial magnetic stimulation can influence the selection of motor programmes.” Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 53: 705–707.)

To be sure, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a much more invasive procedure than lying inside an MRI scanner, as the subject did in Professor Haynes’ experiment: in the case of TMS, a coil is held near a person’s head to generate magnetic field impulses that stimulate underlying brain cells in a way that that can make someone perform a specific action. But I would argue that if powerful magnetic fields can temporarily disrupt free choices, then it should be no surprise that the “choice” made by a person while inside an MRI scanner turns out to be predictable more often than not. Thus the 60% accuracy claimed for Professor Haynes’ experiment, far from showing that human choices are predictable, may only be a measure of how strongly even an MRI scanner can bias the normal exercise of our free will.

But the most damning evidence of all comes from the Wikipedia article on functional magnetic resonance imaging, which makes the following admissions:

While the static magnetic field has no known long-term harmful effect on biological tissue, it can cause damage by pulling in nearby heavy metal objects, converting them to projectiles…

Scanning sessions also subject participants to loud high-pitched noises from Lorentz forces induced in the gradient coils by the rapidly switching current in the powerful static field. The gradient switching can also induce currents in the body causing nerve tingling. Implanted medical devices such as pacemakers could malfunction because of these currents. The radio-frequency field of the excitation coil may heat up the body, and this has to be monitored more carefully in those running a fever, the diabetic, and those with circulatory problems. Local burning from metal necklaces and other jewelry is also a risk. (Italics mine – VJT.)

So these magnetic currents are strong enough to turn metal objects into projectiles, make metal necklaces burn people wearing them, heat up people’s bodies and make their nerves tingle, and even cause pacemakers to malfunction? Why, I have to ask, are we using devices like this to study free will? I could not think of a better illustration of the maxim, “To observe is to disturb,” if I tried.

Does alien hand syndrome disprove free will?

In a recent article entitled, Does alien hand syndrome refute free will? (Center for Bioethics and Human Dignity, Trinity International University, 15 December 2010), Dr. William Cheshire Jr. discusses the strange phenomenon of “alien hand syndrome,” which refers to “a variety of rare neurological conditions in which one extremity, most commonly the left hand, is perceived as not belonging to the person or as having a will of its own, together with observable uncontrollable behavior independent of conscious control.” The seemingly purposeful movements of the alien hand are more than mere spasms: they are goal-directed. For example, while playing checkers, one patient’s left hand made an odd move which he did not wish to make. He corrected the move with his right hand, but to his great annoyance, his left hand then repeated the same odd move.

In his article, Dr. Cheshire explains why he disagrees with psychologists such as Daniel Wegner, who cite these experiments as proof that conscious will is an illusion. He points out that there are important neurological differences between the movements of an alien hand and that of a hand which is normally connected to its motor cortex:

In a patient with a right parietal stroke, alien left hand movements correlated with isolated activation by intentional planning systems of the right primary motor cortex, presumably released from conscious control. Voluntary hand movements, by contrast, activated a distributed network involving not only the primary motor cortex but also premotor areas in the inferior frontal gyrus.

Dr. Cheshire also points out that alien hands have never been known to execute a complex sequence of actions, such as writing a letter. He argues that “the curious gestures of the alien hand and their ostensibly materialistic philosophical implications have not rendered free will obsolete,” and concludes: “To acknowledge that alien hand action is not freely willed would not be to conclude that all nontrivial human action is determined.”

What would disprove free will?

What would create problems for the idea of free will is an experiment showing that we could make a person perform an act – preferably a complex one that requires some planning and control – that they thought was a genuine free choice of theirs, simply by stimulating their brain. Research conducted a few decades ago by the late neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield seemed to point very heavily the other way. His attempts to produce thoughts or decisions by stimulating people’s brains were a total failure: while stimulation could induce flashbacks and vividly evoke old memories, it never generated intentions or choices. On some occasions, Penfield was able to make a patient’s arm go up by stimulating the motor cortex their brain with an electric probe, causing the patient’s arm to move. When Penfield asked the patient, “What’s happening?”, the patient replied, “My arm is moving up.” When Penfield asked, “Are you moving your arm?”, the patient said, “No, it is moving up on its own.” Penfield then said, “OK, now I am going to continue to stimulate your brain, but I want you to make a choice, and not let it go up. Move it in a different direction.” The patient was finally able to resist the movement. (See The Mystery of the Mind: A Critical Study of Consciousness and the Human Brain. Princeton University Press, 1975.) What this suggests, at the very least, is that although local stimulation of the brain causes the body to move the arm one way, it is possible for a higher-level executive decision by the person whose brain is being stimulated to overwrite the local commands of the brain to the body.

However, in a recent article entitled, Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will (Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9, pp. 934-946, 2008), Patrick Haggard reported that directly stimulating the pre-Supplementary Motor Area (pre-SMA) in the brain caused volunteers to report feeling an urge to move the corresponding limb, and sufficient stimulation of that same area caused actual movement of the limb. In one experiment, a patient spotted an apple that belonged to the examiner, and a knife left on purpose on a corner of the testing desk. He peeled the apple and ate it. The examiner asked, “Why did you eat my apple?” The patient replied, “Well, … it was there.” “Are you hungry?” asked the examiner. “No. Well, a bit,” said the patient. “Have you not just finished eating?” “Yes.” “Is this apple yours?” “No.” “So why are you eating it?” “Because it is here.” At first blush, this seems to suggest that the intention to peel and eat an apple can be induced simply by stimulating the brain in the pre-SMA – which runs counter to the idea of free will. Haggard himself acknowledges, though, that the proper function of this area of the brain is to inhibit actions rather than to cause them. It could therefore be argued that stimulation of the pre-SMA interferes with its normal function of inhibiting urges to move, resulting in uninhibited actions which the patient nevertheless found it difficult to account for: he ate the apple “because it was there.” In any case, this is not a true example of intentional agency: typically, an agent is able to supply specific reasons for his or her choices, and in this case, the patient was not.

In a follow-up paper, Moore et al. showed that the subjective feeling of control when performing an intentional act, which can be measured as a temporal linkage between actions and their effects, depends at least partly on the pre-SMA. The authors suggested that the pre-SMA makes a special contribution to sense of agency, housing the predictive mechanisms contributing to the sense of agency. (“Disrupting the experience of control in the human brain: pre-supplementary motor area contributes to the sense of agency.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 22 August 2010, vol. 277 no. 1693, pp. 2503-2509. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0404.)

These findings are welcome news to people interested in the mechanics of free will. It should hardly be surprising that several regions of the brain are involved in decision making, and that interference with one or more of these regions can distort our sense of agency in very odd ways. That, however, does not mean we are not free; all it means is that we are highly complex beings.

A final comment that I would like to make concerns the need for critics of free will to avoid attacking straw men. Scientific studies which purport to discredit the popular notion of free will frequently characterize the concept in dualistic terms, whereas I have argued above that dualism is not essential to the notion of free will. Additionally, many studies incorporate very naive assumptions about the supposedly incorrigible access that I should have to my mental states, if my will is genuinely free. However, there is no reason for a dualist – let alone a proponent of libertarian free will – to adopt such a naive view. Even if the human mind is immaterial, that does not automatically mean that it cannot be fooled into thinking that it made a decision when it didn’t, or vice versa. Whatever version of free will science uncovers in the end, it is likely to be a highly sophisticated one.

Conclusion

I conclude that reports of the death of free will are “greatly exaggerated” (to borrow a phrase from Mark Twain). Before scientists investigate the truth or falsity of mind-body dualism (whether of the Cartesian or Aristotelian variety), they need to focus their attention on the possibility of top-down causation occurring within the brain, where macro-level executive decisions impose a constraint on non-deterministic events taking place in nerve cells at the micro-level, which, when aggregated, results in a specific pattern of neuro-muscular behavior. In this post, I have outlined how this kind of causation would make free will possible.

Is free will a viable concept or not? What do readers think?