|

Professor James M. Tour, who is one of the ten most cited chemists in the world, has been publicly criticized for forthrightly declaring in an online essay that while microevolution (or small changes within a species) is well-understood by scientists, there is no scientist alive today who understands how macroevolution is supposed to work, at a chemical level:

“I do have scientific problems understanding macroevolution as it is usually presented. I simply can not accept it as unreservedly as many of my scientist colleagues do, although I sincerely respect them as scientists. Some of them seem to have little trouble embracing many of evolution’s proposals based upon (or in spite of) archeological, mathematical, biochemical and astrophysical suggestions and evidence, and yet few are experts in all of those areas, or even just two of them. Although most scientists leave few stones unturned in their quest to discern mechanisms before wholeheartedly accepting them, when it comes to the often gross extrapolations between observations and conclusions on macroevolution, scientists, it seems to me, permit unhealthy leeway. When hearing such extrapolations in the academy, when will we cry out, “The emperor has no clothes!”?

“From what I can see, microevolution is a fact; we see it all around us regarding small changes within a species, and biologists demonstrate this procedure in their labs on a daily basis. Hence, there is no argument regarding microevolution. The core of the debate for me, therefore, is the extrapolation of microevolution to macroevolution….

“I simply do not understand, chemically, how macroevolution could have happened. Hence, am I not free to join the ranks of the skeptical and to sign such a statement without reprisals from those that disagree with me? Furthermore, when I, a non-conformist, ask proponents for clarification, they get flustered in public and confessional in private wherein they sheepishly confess that they really don’t understand either. Well, that is all I am saying: I do not understand. But I am saying it publicly as opposed to privately. Does anyone understand the chemical details behind macroevolution?”

– A Layman’s Reflections on Evolution and Creation. An Insider’s View of the Academy.

In response, evolutionary biologist Nick Matzke has accused Professor Tour of being fundamentally ignorant about evolution. According to Matzke, the very idea that “explaining macroevolution is a matter of ‘chemistry’” is a “bizarre, naive, and confused idea.”

Before making his remarks, Matzke might have read benefited from reading a 1996 essay by biochemist and Intelligent Design proponent Professor Michael Behe, entitled, Molecular Machines: Experimental Support for the Design Inference. After a detailed discussion of the biochemistry of vertebrate vision (which is illustrated in the above diagram of the visual cycle), Behe concludes:

In order to say that some function is understood, every relevant step in the process must be elucidated. The relevant steps in biological processes occur ultimately at the molecular level, so a satisfactory explanation of a biological phenomenon such as sight, or digestion, or immunity, must include a molecular explanation. It is no longer sufficient, now that the black box of vision has been opened, for an ‘evolutionary explanation’ of that power to invoke only the anatomical structures of whole eyes, as Darwin did in the 19th century and as most popularizers of evolution continue to do today. Anatomy is, quite simply, irrelevant. So is the fossil record. It does not matter whether or not the fossil record is consistent with evolutionary theory, any more than it mattered in physics that Newton’s theory was consistent with everyday experience. The fossil record has nothing to tell us about, say, whether or how the interactions of 11-cis-retinal with rhodopsin, transducin, and phosphodiesterase could have developed step-by-step. Neither do the patterns of biogeography matter, or of population genetics, or the explanations that evolutionary theory has given for rudimentary organs or species abundance.

The point which Professor Behe makes for vision applies equally to macroevolution as a whole. The relevant steps in macroevolutionary processes occur ultimately at the molecular level, so a satisfactory explanation of macroevolution must include a molecular explanation. Note that Behe is not saying here that biological processes are reducible to molecular chemistry: rather, he is saying that they must include a discussion of molecular chemistry.

Likewise, when Professor Tour publicly declares that no scientist alive today understands the chemical details behind macroevolution, he is not espousing the naïve reductionist line that “explaining macroevolution is a matter of ‘chemistry’”; rather, he is simply pointing out that in order to properly assess the feasibility of Darwinian macroevolution as a theory, we have to ascertain whether it is chemically feasible. If, for some reason, certain macroevolutionary transitions appear to be highly improbable from a chemical standpoint, then that in itself is a good reason to be skeptical of the view that Darwin’s theory of evolution is an all-inclusive theory of biology.

I should like to add that Professor Tour is not an Intelligent Design proponent; he is simply a Darwin skeptic.

In this post, I’d like to discuss macroevolution and revisit the question: “Is skepticism about macroevolution reasonable?”

What is Macroevolution? Some definitions

Before we go any further, however, I’d like to clarify exactly what macroevolution is, by quoting a few definitions from acknowledged experts in the field, for the benefit of readers who (like myself) are not scientists.

Most standard scientific references define macroevolution as evolution “at or beyond the species level,” in the words of Dr. Douglas Theobald, author of 29+ Evidences for Macroevolution. As such, macroevolution consists of changes that occur over the long-term. Macroevolution is defined in contrast with microevolution, which occurs within a species and is defined as “the short-term changes in a population’s gene pool” (Purves W. K., Orians G. H., & Heller H. C., Life: The Science of Biology, 1992, 3rd Edition. Sinauer Associates, Inc., W. H. Freeman and Company, Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA, p. 418).

Macroevolution has also been defined by Professor Jerry Coyne as “large changes in body form or the evolution of one type of plant or animal from another type” (Why Evolution Is True. 2009. Oxford University Press, Glossary, pp. 268-269).

Finally, the term “macroevolution” refers to “evolutionary processes that work across separated gene pools,” whereas the term “microevolution” refers to “evolutionary processes within gene pools, such as the origin and spread of individual gene variants” (Matzke, Nicholas J., and Gross, Paul R. 2006. “Analyzing Critical Analysis: The Fallback Antievolutionist Strategy.” Chapter 2 of Not in Our Classrooms: Why Intelligent Design is Wrong for Our Schools. Scott, E., and Branch, G., eds., Beacon Press, pp. 49-50, italics mine – VJT.)

The following definitions of macroevolution (many of which were retrieved by Mung, Optimus, and other assiduous Uncommon Descent readers) are fairly representative of the scientific literature:

“In evolutionary theory, macroevolution involves common ancestry, descent with modification, speciation, the genealogical relatedness of all life, transformation of species, and large scale functional and structural changes of populations through time, all at or above the species level (Freeman and Herron 2004; Futuyma 1998; Ridley 1993).”

– Theobald, Douglas L. 29+ Evidences for Macroevolution.

Evolutionary change occurs on different scales: ‘microevolution’ is generally equated with events at or below the species level whereas ‘macroevolution’ is change above the species level, including the formation of species. A long-standing issue in evolutionary biology is whether the processes observable in extant populations and species (microevolution) are sufficient to account for the larger-scale changes evident over longer periods of life’s history (macroevolution).

– Carroll, Sean B. 2001 (Feb 8). Nature 409:669.

(Cited by high-school science teacher, creationist and former atheist Richard Peachey here.)

“Macroevolution is evolution on a grand scale – what we see when we look at the over-arching history of life: stability, change, lineages arising, and extinction.”

– Definition of “Macroevolution” at Berkeley University’s “Understanding Evolution” Website.

“The short-term changes in a population’s gene pool… are often called microevolution. Microevolutionary studies are an important part of evolutionary biology because short-term changes can be observed directly and subjected to experimental manipulations. Studies of short-term changes reveal much about evolution, but by themselves they cannot provide a complete explanation of the long-term changes that are often called macroevolution. Macroevolutionary changes can be strongly influenced by events that occur so infrequently that they are unlikely to be observed during microevolutionary studies. Also, because the way evolutionary agents act changes over time, we cannot interpret the past simply by extending today’s results backward in time. Additional types of evidence must be gathered if we wish to understand the course of evolution over more than a billion years.”

– Purves W. K., Orians G. H., & Heller H. C., Life: The Science of Biology, 1992, 3rd Edition. Sinauer Associates, Inc., W. H. Freeman and Company, Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA, p. 418. Cited by Optimus here.

“Creationists usually concede that evolutionary theory provides a satisfactory explanation of micro-evolutionary processes, but they dig in their heels when it comes to macro-evolution. Here, creationists are using the distinction that biologists draw between evolutionary novelties that arise within a species and the appearance of traits that mark the origin of new species.”

– Sober, Elliott. Evidence and Evolution: The Logic Behind the Science. 2008. Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, p. 182. Cited by Mung, here.

“What really excites people – biologists and paleontologists among them – are transitional forms: those fossils that span the gap between two very different kinds of living organisms. Did birds really come from reptiles, and land animals from fish, and whales from land animals? If so, where is the fossil evidence? Even some creationists will admit that minor changes in size and shape might occur over time – a process called microevolution – but they reject the idea that one very different kind of animal or plant can come from another (macroevolution).”

– Coyne, Jerry A. Why Evolution Is True. 2009. Oxford University Press, p. 36. Cited by Mung here.

“MACROEVOLUTION: ‘Major’ evolutionary change, usually thought of as large changes in body form or the evolution of one type of plant or animal from another type. The change from our primate ancestor to modern humans, or from early reptiles to birds, would be considered macroevolution.

“MICROEVOLUTION: ‘Minor’ evolutionary change, such as the change in size or color of a species. One example is the evolution of different skin colors or hair types among human populations; another is the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria.”

– Coyne, Jerry A. Why Evolution Is True. 2009. Oxford University Press, Glossary, pp. 268-269.

“To a biologist, the “it’s just microevolution” argument is painfully obtuse. In normal science, “microevolution” refers to evolutionary processes within gene pools, such as the origin and spread of individual gene variants. “Macroevolution” refers to evolutionary processes that work across separated gene pools. Speciation, a process that can be observed in nature, and that creationists accept, is the boundary between microevolution and macroevolution, because speciation occurs when one gene pool permanently splits into two separate gene pools. A speciation event is a case of macroevolution. So are other events that apply to whole gene pools, such as extinction…

“Evolutionary biologists on both sides of famously contentious debates seem to agree that the definition of macroevolution boils down to “evolution above the species level.””

– Matzke, Nicholas J., and Gross, Paul R. (2006). “Analyzing Critical Analysis: The Fallback Antievolutionist Strategy.” Chapter 2 of Not in Our Classrooms: Why Intelligent Design is Wrong for Our Schools. Scott, E., and Branch, G., eds., Beacon Press, pp. 49-50. Cited by Nick Matzke here.

Terminological ambiguities – different usages of the term “macroevolution”

In the interests of fairness and clarity, I’d like to quote the following passage by biologist Nick Matzke, on the various senses of the word “macroevolution”:

This highlights another thing creationists and other ill-informed antievolutionists just don’t get: just because different writers are talking about the word “macroevolution”, doesn’t mean that they are talking about the same thing. And the discussions aren’t even the same over the decades that those quotes are mined from.

E.g., within macroevolution, scientists study:

speciation (splitting of gene pools, reproductive isolation mechanisms)

lineage dynamics (rates of speciation and extinction; mass extinctions; patterns in phylogenetic trees)

rates of change across species in the fossil record – punctuated equilibrium, contrary to virtually all infuriating, blindly-repeated silliness from antievolutionists, was just about how speciation – the SMALLEST sort of macroevolutionary change – appears in the fossil record. It is about small jumps in morphology between closely-related sister species.

evolution of development, including both “novel” structures and “exaptation” (the latter being far more common than true novelty, whatever “true novelty” means)

the statistical estimation of the history of character change (or biogeographic change, etc.) on phylogenetic trees, and inference of the best statistical models that describe this process

origin of “higher taxa” – this is common in older literature, but Linnaean ranked taxonomy is being gradually abandoned in biology, since we can just use phylogenies without needing any artificial ranks, which were never well-defined anyway

Scientists can be talking about any of the above, or other topics, under the topic of “macroevolution”. And for any of the above, a debate can be had about to what extent an extrapolationist model works as an explanation.

– Matzke, Nicholas J., in a comment on my Uncommon Descent post, A world-famous chemist tells the truth: there’s no scientist alive today who understands macroevolution.

Historical note: Where did the term “macroevolution” come from?

At this point, some readers may be wondering where the term “macroevolution” and “microevolution” came from in the first place. It turns out that they have a long and controversial history, as biologists have flip-flopped over the last ninety years, on the question of whether the former is explicable in terms of the latter:

“I. A. Filipchenko (1929) coined the terms microevolution and macroevolution and argued that one could not be inferred from the other. Macroevolution concerned the origins of higher taxa. Originally, H. F. Osborn (1925), G. G. Simpson, and other American paleontologists did not accept the view that the fossil record could be explained by the accumulation of minute selectable changes over millions of years. But… by 1951 Dobzhansky could confidently declare, ‘Evolution is a change in the genetic composition of populations. The study of mechanisms of evolution falls within the province of population genetics.’ Thus, evolution was seen as a subset of the formal mathematics of population genetics…, and there was nothing in evolutionary biology that fell outside of it. One of the major tenets of the Modern Synthesis has been that of extrapolation: the phenomena of macroevolution, the evolution of species and higher taxa, are fully explained by the microevolutionary processes that gives [sic] rise to varieties within species. Macroevolution can be reduced to microevolution. That is, the origins of higher taxa can be explained by population genetics…” (p. 358)

“The concept that macroevolution could not be derived from microevolution remained as an underground current in evolutionary theory. Every so often, it was brought to the surface by developmentally oriented evolutionary biologists such as Goldschmidt, Waddington, or de Beer… But these attempts to decouple microevolution from macroevolution were either ignored or marginalized (see Gilbert, 1994a). (p. 362)

“Macroevolution was brought back as autonomous entity only after Eldredge and Gould (1972), Stanley (1979), and others postulated an alternative view to the gradualism that characterized the Modern Synthesis. By 1980, Gould claimed that the idea of ‘gradual alleleic [sic] substitution as a mode for all evolutionary change’ was effectively dead. This view did not go unchallenged, and by 1982, Gould’s view had become more specific. It wasn’t that the Modern Synthesis was wrong; rather, it was incomplete. ‘Nothing about microevolutionary population genetics, or any other aspect of microevolutionary theory, is wrong or inadequate at its level…. But it is not everything’… While punctuated equilibrium remained a controversial theory, it did bring to light the question of the autonomy of macroevolution. Indeed, the failure of microevolutionary biology to distinguish between punctuated equilibrium and gradualism demonstrated its weakness when applied to macroevolution…. Molecular studies… were similarly pointing to ‘evolution at two levels,’ one molecular, the other morphological. Thus, by the early 1980s, numerous paleontologists and evolutionary biologists (Gould, Stanley, Eldredge, Verba [sic, should be Vrba], and mostly critically, Ayala) came to the conclusion that although macroevolutionary phenomena were underlain by microevolutionary phenomena, the two areas were autonomous and that macroevolutionary processes could not be explained solely by microevolutionary events.” (p. 362)

– Scott F. Gilbert, John M. Opitz, and Rudolf A. Raff. 1996. “Resynthesizing Evolutionary and Developmental Biology.” Developmental Biology 173:357-372.

Thus Professor Tour’s public skepticism regarding whether macroevolution is merely an extrapolation of microevolution (as orthodox Darwinists have traditionally maintained) or whether it represents something fundamentally different, has some prominent scientific defenders. Mr. Matzke will doubtless point out that these anti-reductionist scientists were avowed evolutionists, whereas Professor Tour is not, and that’s perfectly true. In reply, I would argue that Tour has every right as a scientist to not only critique, on chemical grounds, the conventional view that macroevolution is merely microevolution writ large, but also to argue that the alternative evolutionary views put forward by scientists (such as Gould) who disagree with the orthodox Darwinian view are no less deficient, from a chemical standpoint.

In the Appendix at the end of my post, I’ve quoted the opinions of various scientists as to whether macroevolution can be regarded as merely an extension of microevolution. As the quotes below confirm, the standard view (espoused by Dawkins, Prothero and Coyne) is that macroevolution is indeed nothing more than microevolution writ large. This was what the proponents of the modern evolutionary synthesis maintained. Even de Beer and Eldredge can be cited in support of this view. Although there are some prominent scientific dissenters from the “standard” view (Gould, Lewin, Erwin, Carroll and Macneill), they seem to constitute a minority.

Nick Matzke’s scientific quarrel with Professor Tour

I’d now like to address the central point of contention between Professor Tour and biologist Nick Matzke. Matzke recently contended that Professor James Tour was making a huge category mistake in his demand for a chemical explanation of how macroevolution works. Matzke argued that Tour was trying to explain evolution at the wrong level, and lambasted Tour for “the entire bizarre, naive, and confused idea that explaining macroevolution is a matter of ‘chemistry’, when it is much more closely connected to ecology, biogeography, environmental change, natural selection, etc.” and then added,

“Now, if what he meant wasn’t ‘macroevolution’, but specifically the evolution of developmental systems, i.e. evo-devo – which is what those articles are about – then the request for ‘chemical details’ would make a tiny bit more sense, but it’s still bizarre.”

Matzke concluded:

“What any serious student of the question would look at would be the homologies, genetics, mutations, selection pressures, and functional shifts involved in the origin of a particular structure. Pretending that it’s just ‘chemistry’ that is important, and chemistry only, is just weird. It’s some old-fashioned tidbit of reductionism adopted by someone who apparently can’t be bothered to learn the basics about a field before proclaiming it fallacious.”

Matzke is putting words into Professor Tour’s mouth here: nowhere does he claim that “it’s just ‘chemistry’ that is important, and chemistry only.” Nor has Tour ever espoused reductionism. Rather, what he insists is that macroevolutionary processes have to be describable at a chemical level. This certainly seems to be a reasonable request, and if Matzke thinks it isn’t, he should tell us why.

Nevertheless, I have to confess that when I first read Nick Matzke’s comments, I was rather perplexed. Could an eminent scientist such as Professor Tour have really made such an elementary mistake as the one which Matzke attributes to him? It seemed very unlikely.

I get mail from Spain

A few days ago, a very perceptive reader from Spain emailed me with an insightful comment. He pointed out that in a recent post on 15 February 2013, entitled, Is the genetic code a real code?, I had critiqued the view defended by Alan Fox, that the genetic code was not a real code, and that everything in the process of protein synthesis could be described in terms of strict chemistry, without the need to invoke a code in order to explain it. On Fox’s view, “DNA transcription and translation is a chemical chain of reactions that depends on the spatial conformation and inherent chemical properties of atoms and molecules.” Fox added that whenever scientists refer to a code, they are merely using a convenient shorthand:

I see no communicative element in the chemical processes that occur when DNA sequences are transcribed into RNA and translated into polypeptide sequences. It’s all a result of the inherent physical and chemical properties of the interacting molecules… To lump chemical processes in with aspects of linguistics is such a stretch that any set that encompasses both is large enough and fuzzy enough to be meaningless… At the cellular and sub-cellular level and consequently and cumulatively at the level of the organism there is a huge amount of communication going on. It is chemical communication… “Encode” could be used as a defined shorthand for some step in the chemical processes that go on in the cell, of course. Maybe there is a scientific definition in the context of biochemistry.

Now that’s reductionism for you. And it’s a form of reductionism espoused by many of Darwin’s defenders, when discussing the origin of life.

My reader from Spain then pointed out that if Fox’s reductionist view were true, then all bio-functional processes (including those that occur in evolution) would be reducible to chemistry, and evolution itself would be nothing but a series of transitions between different chemical processes. In that case, macroevolution would have to be ultimately explicable in terms of chemistry, and Professor Tour’s request that some scientist should be able to explain how it works at the chemical level would be an entirely legitimate one.

So it is surprising that Nick Matzke declares himself to be shocked, shocked, when a chemistry asks him to explain how macroevolution works at a chemical level, but does not bat an eyelid when his fellow Darwinists roundly assert that the origin of the genetic code can be explained at the chemical level. Is there an inconsistency here? It certainly seems so!

The only way in which Matzke could legitimately avoid Professor Tour’s demand for an explanation of how macroevolution works at the chemical level is by maintaining that the capacity to evolve, at the macro level (i.e. at the species level and above), is an emergent property of organisms which supervenes upon, but is not reducible to, their underlying biochemistry. In that case, there should be higher-level laws of Nature that explain how macroevolution works. Matzke would then be espousing a form of holism.

Does holism offer a way out for Matzke?

Now, I have no problem if Matzke wants to publicly endorse holism, in order to explain macroevolution. But I would then ask him: where are the scientific laws that explain how macroevolution works? At this point, we should recall Galileo’s dictum that the universe is written in the language of mathematics. If there are “higher-level” laws of macroevolution, then they have to be written in that language. Where’s the math?

Reading through the various definitions of macroevolution that assiduous readers on Uncommon Descent had managed to dig up from the scientific literature, my attention was drawn to the following comment made on Uncommon Descent back in 2006, by Cornell evolutionary biologist Allen Macneill, a man for whom I have the highest respect:

“In other words, microevolution (i.e. natural selection, genetic drift, and other processes that happen anagenetically at the population level) and macroevolution (i.e. extinction/adaptive radiation, genetic innovation, and symbiosis that happen cladogenetically at the species level and above) are in many ways fundamentally different processes with fundamentally different mechanisms. Furthermore, for reasons beyond the scope of this thread, macroevolution is probably not mathematically modelable in the way that microevolution has historically been.”

– MacNeill, Allen, in a comment on “We is Junk” article by PaV at Uncommon Descent, November 10, 2006.

When I read that remark, I had an “Ah-ha!” moment. I realized then that the evidential case for macroevolution is like a house built on a foundation of sand.

Surprise! There’s no satisfactory mathematical model for macroevolution, at the present time

In 2006, Professor Allen Macneill acknowledged that macroevolution is not mathematically modelable in the way that microevolution is. He could have meant that macroevolution is not mathematically modelable at all; alternatively, he may have simply meant that macroevolutionary models are not as detailed as microevolutionary models. If he meant the latter, then I would ask: where’s the mathematics that explains macroevolution? Surprisingly, it turns out that there is currently no adequate mathematical model for Darwinian macroevolution. Professor James Tour’s remark that “The Emperor has no clothes” is spot-on.

Evolutionary biology has certainly been the subject of extensive mathematical theorizing. The overall name for this field is population genetics, or the study of allele frequency distribution and change under the influence of the four main evolutionary processes: natural selection, genetic drift, mutation and gene flow. Population genetics attempts to explain speciation within this framework. However, at the present time, there is no mathematical model – not even a “toy model” – showing that Darwin’s theory of macroevolution can even work, much less work within the time available. Darwinist mathematicians themselves have admitted as much.

In 2011, I had the good fortune to listen to a one-hour talk posted on Youtube, entitled, Life as Evolving Software. The talk was given by Professor Gregory Chaitin, a world-famous mathematician and computer scientist, at PPGC UFRGS (Portal do Programa de Pos-Graduacao em Computacao da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.Mestrado), in Brazil, on 2 May 2011. I was profoundly impressed by Professor Chaitin’s talk, because he was very honest and up-front about the mathematical shortcomings of the theory of evolution in its current form. As a mathematician who is committed to Darwinism, Chaitin is trying to create a new mathematical version of Darwin’s theory which proves that evolution can really work. He has recently written a book, Proving Darwin: Making Biology Mathematical (Random House, 2012, ISBN: 978-0-375-42314-7), which elaborates on his ideas.

Here are some excerpts from Chaitin’s talk, part of which I transcribed in my post, At last, a Darwinist mathematician tells the truth about evolution (November 6, 2011):

I’m trying to create a new field, and I’d like to invite you all to leap in, join [me] if you feel like it. I think we have a remarkable opportunity to create a kind of a theoretical mathematical biology…

So let me tell you a little bit about this viewpoint … of biology which I think may enable us to create a new … mathematical version of Darwin’s theory, maybe even prove that evolution works for the skeptics who don’t believe it…

I don’t want evolution to stagnate, because as a pure mathematician, if the system evolves and it stops evolving, that’s like it never evolved at all… I want to prove that evolution can go on forever…

OK, so software is everywhere there, and what I want to do is make a theory about randomly evolving, mutating and evolving software – a little toy model of evolution where I can prove theorems, because I love Darwin’s theory, I have nothing against it, but, you know, it’s just an empirical theory. As a pure mathematician, that’s not good enough…

… John Maynard Smith is saying that we define life as something that evolves according to Darwin’s theory of evolution. Now this may seem that it’s totally circular reasoning, but it’s not. It’s not that kind of reasoning, because the whole point, as a pure mathematician, is to prove that there is something in the world of pure math that satisfies this definition – you know, to invent a mathematical life-form in the Pythagorean world that I can prove actually does evolve according to Darwin’s theory, and to prove that there is something which satisfies this definition of being alive. And that will be at least a proof that in some toy model, Darwin’s theory of evolution works – which I regard as the first step in developing this as a theory, this viewpoint of life as evolving software….

…I want to know what is the simplest thing I need mathematically to show that evolution by natural selection works on it? You see, so this will be the simplest possible life form that I can come up with….

The first thing I … want to see is: how fast will this system evolve? How big will the fitness be? How big will the number be that these organisms name? How quickly will they name the really big numbers? So how can we measure the rate of evolutionary progress, or mathematical creativity of my little mathematicians, these programs? Well, the way to measure the rate of progress, or creativity, in this model, is to define a thing called the Busy Beaver function. One way to define it is the largest fitness of any program of N bits in size. It’s the biggest whole number without a sign that can be calculated if you could name it, with a program of N bits in size….

So what happens if we do that, which is sort of cumulative random evolution, the real thing? Well, here’s the result. You’re going to reach Busy Beaver function N in a time that is – you can estimate it to be between order of N squared and order of N cubed. Actually this is an upper bound. I don’t have a lower bound on this. This is a piece of research which I would like to see somebody do – or myself for that matter – but for now it’s just an upper bound. OK, so what does this mean? This means, I will put it this way. I was very pleased initially with this.

Table:

Exhaustive search reaches fitness BB(N) in time 2^N.

Intelligent Design reaches fitness BB(N) in time N. (That’s the fastest possible regime.)

Random evolution reaches fitness BB(N) in time between N^2 and N^3.This means that picking the mutations at random is almost as good as picking them the best possible way…

But I told a friend of mine … about this result. He doesn’t like Darwinian evolution, and he told me, “Well, you can look at this the other way if you want. This is actually much too slow to justify Darwinian evolution on planet Earth. And if you think about it, he’s right… If you make an estimate, the human genome is something on the order of a gigabyte of bits. So it’s … let’s say a billion bits – actually 6 x 10^9 bits, I think it is, roughly – … so we’re looking at programs up to about that size [here he points to N^2 on the slide] in bits, and N is about of the order of a billion, 10^9, and the time, he said … that’s a very big number, and you would need this to be linear, for this to have happened on planet Earth, because if you take something of the order of 10^9 and you square it or you cube it, well … forget it. There isn’t enough time in the history of the Earth … Even though it’s fast theoretically, it’s too slow to work. He said, “You really need something more or less linear.” And he has a point…

Professor Chaitin’s point here is that if even a process of intelligently guided evolution takes, say, one billion years (1,000,000,000 years) to reach its goal, then an unguided process of cumulative random evolution (i.e. Darwin’s theory) will take one billion times one billion years to reach the same goal, or 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 years. That’s one quintillion years. The problem here should be obvious: the Earth is less than five billion years old, and even the universe is less than 14 billion years old.

Debunking a popular myth: ”There’s plenty of time for evolution”

At this point, I imagine Matzke will want to cite a 2010 paper in Proceedings of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), titled “There’s plenty of time for evolution” by Herbert S. Wilf and Warren J. Ewens, a biologist and a mathematician at the University of Pennsylvania. Although it does not refer to them by name, there’s little doubt that Wilf and Ewens intended their work to respond to the arguments put forward by intelligent-design proponents, since it declares in its first paragraph:

…One of the main objections that have been raised holds that there has not been enough time for all of the species complexity that we see to have evolved by random mutations. Our purpose here is to analyze this process, and our conclusion is that when one takes account of the role of natural selection in a reasonable way, there has been ample time for the evolution that we observe to have taken place.

Evolutionary biologist Professor Jerry Coyne praised the paper, saying that it provides “one step towards dispelling the idea that Darwinian evolution works too slowly to account for the diversity of life on Earth today.” Famous last words.

A 2012 paper, Time and Information in Evolution, by Winston Ewert, Ann Gauger, William Dembski and Robert Marks II, contains a crushing refutation of Wilf and Ewens’ claim that there’s plenty of time for evolution to occur. The authors of the new paper offer a long list of reasons why Wilf and Ewens’ model of evolution isn’t biologically realistic:

Wilf and Ewens argue in a recent paper that there is plenty of time for evolution to occur. They base this claim on a mathematical model in which beneficial mutations accumulate simultaneously and independently, thus allowing changes that require a large number of mutations to evolve over comparatively short time periods. Because changes evolve independently and in parallel rather than sequentially, their model scales logarithmically rather than exponentially. This approach does not accurately reflect biological evolution, however, for two main reasons. First, within their model are implicit information sources, including the equivalent of a highly informed oracle that prophesies when a mutation is “correct,” thus accelerating the search by the evolutionary process. Natural selection, in contrast, does not have access to information about future benefits of a particular mutation, or where in the global fitness landscape a particular mutation is relative to a particular target. It can only assess mutations based on their current effect on fitness in the local fitness landscape. Thus the presence of this oracle makes their model radically different from a real biological search through fitness space. Wilf and Ewens also make unrealistic biological assumptions that, in effect, simplify the search. They assume no epistasis between beneficial mutations, no linkage between loci, and an unrealistic population size and base mutation rate, thus increasing the pool of beneficial mutations to be searched. They neglect the effects of genetic drift on the probability of fixation and the negative effects of simultaneously accumulating deleterious mutations. Finally, in their model they represent each genetic locus as a single letter. By doing so, they ignore the enormous sequence complexity of actual genetic loci (typically hundreds or thousands of nucleotides long), and vastly oversimplify the search for functional variants. In similar fashion, they assume that each evolutionary “advance” requires a change to just one locus, despite the clear evidence that most biological functions are the product of multiple gene products working together. Ignoring these biological realities infuses considerable active information into their model and eases the model’s evolutionary process.

After reading this devastating refutation of Wilf and Ewens’ 2012 paper, I think it would be fair to conclude that we don’t currently have an adequate mathematical model explaining how macroevolution can occur at all, let alone one showing that it can take place within the time available. Four billion years might sound like a long time, but if your model requires not billions, but quintillions of years for it to work, then obviously, your model of macroevolution isn’t mathematically up to scratch.

Debunking another popular myth: “The eye could have evolved in a relatively short period.”

|

Parts of the eye: 1. vitreous body 2. ora serrata 3. ciliary muscle 4. ciliary zonules 5. canal of Schlemm 6. pupil 7. anterior chamber 8. cornea 9. iris 10. lens cortex 11. lens nucleus 12. ciliary process 13. conjunctiva 14. inferior oblique muscle 15. inferior rectus muscle 16. medial rectus muscle 17. retinal arteries and veins 18. optic disc 19. dura mater 20. central retinal artery 21. central retinal vein 22. optic nerve 23. vorticose vein 24. bulbar sheath 25. macula 26. fovea 27. sclera 28. choroid 29. superior rectus muscle 30. retina. Image courtesy of Chabacano and Wikipedia.

In 1994, Dan-Erik Nilsson and Susanne Pelger of Lund University in Sweden wrote a paper entitled, A Pessimistic Estimate of the Time Required for an Eye to Evolve (Proceedings: Biological Sciences, Vol. 256, No. 1345, April 22 1994, pp. 53-58) in which they cautiously estimated the time required for a fully-developed lens eye to develop from a light-sensitive spot to be no more than 360,000 years or so.

In 2003, the mathematician David Berlinski wrote an incisive critique of this outlandish claim. (See here for Nilsson’s response.) Some of Berlinski’s contentions turned out to be based on a misunderstanding of Nilsson and Pelger’s data, but Berlinski scored significantly when he pointed out that Nilsson and Pelger’s paper was lacking in the mathematical details one might expect in support of their claim that the eye took only 360,000 years to evolve:

“Nilsson and Pelger’s paper contains no computer simulation, and no computer simulation has been forthcoming from them in all the years since its initial publication…

“There are two equations in Nilsson and Pelger’s paper, and neither requires a computer for its solution; and there are no others.”

Indeed, Nilsson had even admitted as much, in correspondence with Berlinski:

“You are right that my article with Pelger is not based on computer simulation of eye evolution. I do not know of anyone else who [has] successfully tried to make such a simulation either. But we are currently working on it.”

That was in 2001. As far as I am aware, no simulation has since been forthcoming from Nilsson and Pelger, although as we’ll see below, a genetic algorithm developed by an Israeli researcher in 2007 demonstrated that their model was based on wildly optimistic assumptions about evolutionary pathways.

In the meantime, Nilsson and Pelger’s 1994 paper has been gleefully cited by evolutionary biologists as proof that the origin of complex structures is mathematically modelable. Here is how Professor Jerry Coyne describes Nilsson and Pelger’s work in his book, Why Evolution Is True:

We can, starting with a simple precursor, actually model the evolution of the eye and see whether selection can turn that precursor into a more complex eye within a reasonable amount of time. Dan Nilsson and Susanne Pelger of Lund University in Sweden made such a mathematical model, starting with a patch of light-sensitive cells backed by a pigment layer (a retina). They then allowed the tissues around this structure to deform themselves randomly, limiting the amount of change to only 1% of size or thickness at each step. To mimic natural selection, the model accepted only mutations that improved the visual acuity, and rejected those that degraded it.

Within an amazingly short time, the model yielded a complex eye, going through stages similar to the real-animal series described above. The eyes folded inward to form a cup, the cup became capped with a transparent surface, and the interior of the cup gelled to form not only a lens, but a lens with dimensions that produced the best possible image.

Beginning with a flatworm-like eyespot, then, the model produced something like the complex eye of vertebrates, all through a series of tiny adaptive steps – 1,829 of them, to be exact. But Nilsson and Pelget could also calculate how long this process would take. To do this, they made some assumptions about how much genetic variation for eye shape existed in the population that began experiencing selection, and how strongly selection would favor each useful step in eye size. These assumptions were deliberately conservative, assuming that there were reasonable but not large amounts of genetic variation and that natural selection was very weak. Nevertheless, the eye evolved very quickly: the entire process from rudimentary light-patch to camera eye took fewer than 400,000 years.

– Coyne, Jerry A. Why Evolution Is True. 2009. Oxford University Press, p. 155.

I’d like to point out here that Coyne’s starry-eyed description of Nilsson and Pelger’s research overlooks a vital point raised by Professor Michael Behe in his article, Molecular Machines: Experimental Support for the Design Inference. Readers will recall that Behe declared:

“The relevant steps in biological processes occur ultimately at the molecular level, so a satisfactory explanation of a biological phenomenon such as sight, or digestion, or immunity, must include a molecular explanation. It is no longer sufficient, now that the black box of vision has been opened, for an ‘evolutionary explanation’ of that power to invoke only the anatomical structures of whole eyes, as Darwin did in the 19th century and as most popularizers of evolution continue to do today. Anatomy is, quite simply, irrelevant.”

Nilsson and Pelger’s mathematical calculations addressed the evolution of the eye’s anatomy, but they said nothing about the underlying biochemistry. Using Behe’s criteria, we can see at once that their macroevolutionary model of the evolution of the eye is a failure. Professor James Tour would dismiss it on similar grounds. He would doubtless ask, rhetorically: “Does anyone understand the chemical details behind the macroevolution of the eye?” I hope that Nick Matzke will now concede that this is a reasonable question.

A more skeptical assessment of Nilsson and Pelger’s 1994 paper can be found in an online applied physics thesis by Dov Rhodes, entitled, Approximating the Evolution Time of the Eye: A Genetic Algorithms Approach. The thesis makes for fascinating reading. I shall quote a few brief excerpts:

“A paper published in 1994 by the Swedish scientists Nilsson and Pelger [6] gained immediate worldwide fame for describing the evolution process for an eye, and approximating the time required for an eye to evolve from a simple patch that sense electromagnetic radiation. Nilsson and Pelger (NP) outlined an evolutionary path, where by minute improvements on each step a cameratype eye can evolve in approximately 360,000 years, which is extremely fast on an evolutionary time scale… (p. 1)

“The main problem with the NP model is that although the evolutionary path that it describes might be a legitimate one, it neglects consideration for divergent paths. It is easy to construct a situation in which the best temporary option for the improvement of an eye does not lead towards the development of the globally optimal solution. This idea motivates our alternative approach, the method of genetic algorithms. In this paper we use the genetic algorithm with a simplified (2-dimensional) version of NP’s setup and show the error in their approach. We argue that if their approach is mistaken in the simplified model, it is even farther from reality in the full evolutionary setting. (p. 2)

“Although the paraboloid landscape guarantees convergence, the GA is still a probabilistic algorithm and thus will not always converge quickly. As in evolution, the most efficient path is not necessarily the one taken. This fact suggests that our already conservative value of lambda = 5.41 would be even larger if compared with a real deterministic algorithm such as the NP (Nilsson-Pelger) model. Even though their computation accounts to some extent for the average probability of evolutionary development over time, it fails to consider the countless different evolutionary paths, and instead chooses just one.

“Rather than 360 thousand generations, a reasonable lower bound should be at least 5*360,000 = 1.8*10^6 generations, and if our previous speculations have merit, an order of magnitude higher would ramp up the estimate to around 18 million generations. Future experiments that would be useful for improving the accuracy of our results might involve varying the mutation parameter, and most importantly letting algorithms run for longer, allowing the lower bound for convergence to be pushed even higher.” (p. 15)

What Rhodes’ paper demonstrates is that the 1994 estimate by Nilsson and Pelger of how long it took the eye to evolve is more like a case of intelligently guided evolution than Darwinian evolution. As Rhodes puts it: “Even though their computation accounts to some extent for the average probability of evolutionary development over time, it fails to consider the countless different evolutionary paths, and instead chooses just one.”

Why the evidence for unguided Darwinian macroevolution is like a house built on a foundation of sand

We have seen that there’s curently no good theory that can serve as an adequate model for Darwinian macroevolution – even at a “holistic” level. As we saw, Professor Gregory Chaitin’s toy models don’t go down to the chemical level requested by Professor James Tour, but these models have failed to validate Darwin’s theory of evolution, or even show that it could work.

At this point, there is an alternative line that Matzke might want to take. He could claim that macroevolution is ultimately explicable in terms of bottom-level laws and physical processes, but that unfortunately, scientists haven’t discovered what they are yet. From a theoretical perspective, reductionism would then be true after all, and the chemical explanation of macroevolution demanded by Professor Tour could be given. From a practical standpoint, however, it would be impossible for scientists to provide such an explanation within the foreseeable future.

If Matzke wishes to take this road, then he is tacitly admitting that scientists don’t yet know either the scientific laws (which are written in the language of mathematics) or the physical processes that ultimately explain and drive macroevolution. But if they don’t know either of these, then I would ask him: why should we believe that it actually occurs? After all, mathematics, scientific laws and observed processes are supposed to form the basis of all scientific explanation. If none of these provides support for Darwinian macroevolution, then why on earth should we accept it? Indeed, why does macroevolution belong in the province of science at all, if its scientific basis cannot be demonstrated?

Are there any good scientific parallels to the lack of evidence for macroevolution?

At this point in the discussion, Darwinists will often cite two historical illustrations to support their claim that belief in macroevolution can still be reasonable, even if we currently lack a mathematical model for it. The two examples they love to mention are continental drift (the mechanism of which remained an unsolved mystery, long after good empirical evidence supporting it was discovered by scientists) and gravity (the theoretical basis of which is still not fully understood by scientists, although it is currently regarded as a curvature in the fabric of spacetime).

However, the analogy with continental drift is a poor one. After all, the process of continental drift can be observed and measured, and there is no micro/macro distinction. Extrapolate continental movements back 200 million years in time, and you end up with the super-continent of Pangaea.

Nor will gravity save the evolutionist: it can be described mathematically (e.g. by Newton’s law of universal gravitation, F = G.(m1.m2)/r^2), even if its physical basis remains mysterious.

Matzke: but macroevolution can be demonstrated! –

In a comment on my recent thread, A world-famous chemist tells the truth: there’s no scientist alive today who understands macroevolution, Nick Matzke stoutly maintained that there’s plenty of observational evidence for macroevolution:

Dog breeds and many other domestic plants and animals have morphological differences much larger than the “macroevolutionary” differences typically seen between species in a genus or even family. Cue excuse for not accepting the evidence you JUST requested in 3, 2, 1…

OK, Nick. Here’s my excuse. There’s a saying that a picture is worth a thousand words. Here’s a photo of the skeleton of a Great Dane, next to a Chihuahua:

|

Apart from size, there’s not much of a difference in the skeletons, is there?

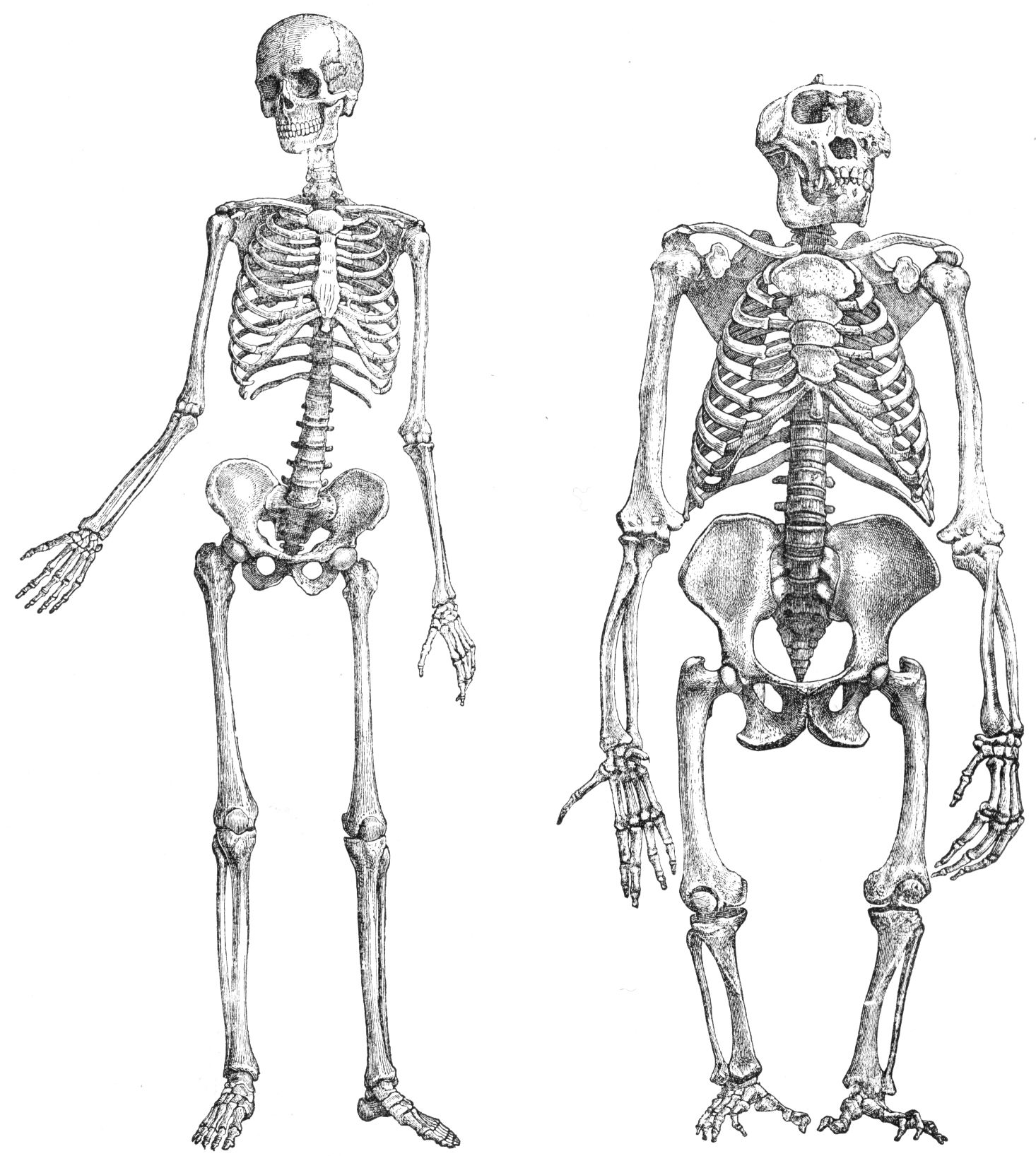

“What about a human being and a great ape?” you might ask. Here’s another picture, showing a human skeleton and a gorilla skeleton. Not so similar, are they?

|

Chimpanzees and gorillas are man’s closest living relatives. The anatomical differences between humans and chimpanzees, which are quite extensive, are conveniently summarized in a handout prepared by Anthropology Professor Claud A. Ramblett the University of Texas, entitled, Primate Anatomy. Anyone who thinks that a series of random stepwise mutations, culled by the non-random but unguided process of natural selection, can account for the anatomical differences between humans and chimpanzees, should read this article very carefully. What it reveals is that an entire ensuite of changes, relating to the skull, teeth, vertebrae, thorax, shoulder, arms, hands, pelvis, legs and feet, not to mention the rate of skeletal maturation and method of locomotion, would have been required, in order to transform the common ancestor of humans and chimps into creatures like ourselves. Given the sheer diversity of changes that would have been required, it is surely reasonable to ask whether an unguided process, such as Darwinian macroevolution, could have accomplished this feat over a period of a few million years.

It is often claimed that neoteny accounts for many of the anatomical differences between human beings and great apes, and that humans resemble juvenile apes. Readers will be able to see how nonsensical this view is, by examining the following photo (WARNING: this may upset some viewers) of a baby human skeleton alongside a baby chimpanzee skeleton. Even at a young age, the differences between the two species are marked. I would invite readers to look at the skull, the rib cage, the pelvis, the arm bones and leg bones, and the hands and feet, and judge for themselves.

Now, I happen to accept the common ancestry of humans and chimpanzees, although I’d also like to point out that it’s illogical to infer from the fact that a change is known to have occurred in the past that the change in question occurred as a result of physical processes that are known to us today. We don’t know that. Common descent is one thing; common descent as a result of Darwinian natural selection is quite another.

I’d also be inclined to agree with Nick Matzke’s claim that Homo erectus (broadly defined, to include Homo ergaster) is a direct ancestor of modern Homo sapiens, although I should point out in passing that evolutionary biologist Professor Coyne is far more circumspect when he writes of Homo erectus: “It may, though, have left two famous descendants: H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis, known respectively as “archaic H. sapiens” and the famous ‘Neanderthal man.’” But even if we compare Homo erectus (who had a smaller brain than that of modern humans, but who was virtually identical with us from the neck down) with modern Homo sapiens, the neurological differences are quite profound. There were changes in the prefrontal cortex that took place about 700,000 years ago, with the emergence of Homo heidelbergensis (Heidelberg man), which enabled long-term planning and inhibitory control, making self-sacrifice for the good of the group and life-long monogamy possible. Later on, there were also changes in the temporoparietal cortex, with the emergence of modern Homo sapiens, about 200,000 years ago, making possible the emergence of art, symbolism and religious rituals. Readers can learn more about these changes (which I’ll be writing about in a future post) in the following two articles:

Paleolithic public goods games: why human culture and cooperation did not evolve in one step by Benoit Dubreuil, in Biology and Philosophy (2010) 25:53–73, DOI 10.1007/s10539-009-9177-7.

The First Appearance of Symmetry in the Human Lineage: where Perception meets Art (careful: large file!) by Dr. Derek Hodgson. In Symmetry, 2011, 3, 37-53; doi:10.3390/3010037

Just as with vision, the changes required to enlarge the prefrontal cortex and the temporoparietal cortex in modern man had to be realized at the molecular level. There’s no escaping the nitty-gritty: if we’re going to explain how modern man got his brain, we’re going to have to supply the chemical details as well as genetic and anatomical details.

The necessary changes in the brains of our hominid ancestors which allowed human beings, in the true sense of the word, to emerge, were not trivial ones, and they were not merely a matter of “scaling up” a more primitive brain. We also forget that the human brain is the most complex machine known in the universe. We know that random changes plus non-random “selection” are not enough by themselves to create a pattern or a function – such as the function of being able to engage in long-term planning and inhibitory control, which characterized Heidelberg man, who emerged 700,000 years ago. As Professor William Dembski puts it in his essay, Conservation of Information Made Simple:

It’s easy to write computer simulations that feature selection, replication, and mutation (or SURVIVAL writ large, or differential survival and reproduction, or any such reduction of evolution to Darwinian principles) – and that go absolutely nowhere. Taken together, selection, replication, and mutation are not a magic bullet, and need not solve any interesting problems or produce any salient patterns.

If someone wants to argue that random copying errors plus non-random death are sufficient to make a brain with new cognitive abilities, I shall demand evidence before I believe such a claim. At the very least, I’d like a plausible sequence of genetic changes relating to the development of the human brain, that could have transformed an Australopithecus into Homo erectus and finally modern man, without the need for intelligent guidance..

In his online essay, 29+ Evidences for Macroevolution, Dr. Douglas Theobald, makes some truly outlandish statements about evolutionary change:

A more recent paper evaluating the evolutionary rate in guppies in the wild found rates ranging from 4000 to 45,000 darwins (Reznick 1997). [A darwin is a unit of evolutionary change – VJT.] Note that a sustained rate of “only” 400 darwins is sufficient to transform a mouse into an elephant in a mere 10,000 years (Gingerich 1983).

One of the most extreme examples of rapid evolution was when the hominid cerebellum doubled in size within ~100,000 years during the Pleistocene (Rightmire 1985). This “unique and staggering” acceleration in evolutionary rate was only 7 darwins (Williams 1992, p. 132). This rate converts to a minuscule 0.02% increase per generation, at most. For comparison, the fastest rate observed in the fossil record in the Gingerich study was 37 darwins over one thousand years, and this corresponds to, at most, a 0.06% change per generation.

I hope that by now, readers can see how naive that kind of argument is. Professor Tour is right: anatomical explanations are not enough. We do need to look at the underlying chemistry.

APPENDIX: What scientists say about the relation between macroevolution and microevolution

(a) Scientific authorities who SUPPORT the view that macroevolution is just an extrapolation of microevolution, over long periods of time

“Along with the reductionist attitude that organisms are nothing more than vessels to carry their genes came the extrapolation that the tiny genetic and phenotypic changes observed in fruit flies and lab rats were sufficient to explain all of evolution. This defines all evolution as microevolution, the gradual and tiny changes that cause different wing veins in a fruit fly or a slightly longer tail in a rat. From this, Neo-Darwinism extrapolates all larger evolutionary changes (macroevolution) as just microevolution writ large. These central tenets – reductionism, panselectionism, extrapolationism, and gradualism – were central to the Neo-Darwinian orthodoxy of the 1940s and 1950s and are still followed by the majority of evolutionary biologists today.”

– Prothero, Donald R. Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters. 2007. Cited by Mung here.

“Many who reject darwinism on religious grounds . . . argue that such small changes [as seen in selective breeding] cannot explain the evolution of new groups of plants and animals. This argument defies common sense. When, after a Christmas visit, we watch grandma leave on the train to Miami, we assume that the rest of her journey will be an extrapolation of that first quarter-mile. A creationist unwilling to extrapolate from micro- to macroevolution is as irrational as an observer who assumes that, after grandma’s train disappears around the bend, it is seized by divine forces and instantly transported to Florida.”

– Coyne, Jerry A. 2001 (Aug 19). Nature 412:587. Cited by Richard Peachey here.

“…we shouldn’t expect to see more than small changes in one or a few features of a species – what is known as microevolutionary change. Given the gradual pace of evolution, it’s unreasonable to expect to see selection transforming one “type” of plant or animal to another – so-called macroevolution – within a human lifetime. Though macroevolution is occurring today, we simply won’t be around long enough to see it. Remember that the issue is not whether macroevolutionary change happens – we already know from the fossil record that it does – but whether it was caused by natural selection, and whether natural selection can build complex features and organisms.”

– Coyne, Jerry A. Why Evolution Is True. 2009. Oxford University Press, p. 144. Cited by Mung here.

“So where are we? We know that a process very like natural selection – animal and plant breeding – has taken the genetic variation present in wild species and from it created huge “evolutionary” transformations. We know that these transformations can be much larger, and faster, than real evolutionary change that took place in the past. We’ve seen that selection operates in the laboratory, in microorganisms that cause disease, and in the wild. We know of no adaptations that absolutely could not have been molded by natural selection, and in many cases we can plausibly infer how selection did mold them. And mathematical models show that natural selection can produce complex features easily and quickly. The obvious conclusion: we can provisionally assume that natural selection is the cause of all adaptive evolution – though not of every feature of evolution, since genetic drift can also play a role.

“True, breeders haven’t turned a cat into a dog, and laboratory studies haven’t turned a bacterium into an amoeba (although, as we’ve seen, new bacterial species have arisen in the lab). But it is foolish to think that these are serious objections to natural selection. Big transformations take time – huge spans of it. To really see the power of selection, we must extrapolate the small changes that selection creates in our lifetime over the millions of years that it has really had to work in nature.”

– Coyne, Jerry A. Why Evolution Is True. 2009. Oxford University Press, p. 155.

“The claim that microevolution can’t be extrapolated to macroevolution is ubiquitous among ID advocates and the creationists who preceded them…. it is nothing more than standard creation science terminology for the creationist claim that various groups of organisms were specially created by God, with specified limits on how far they could change over time.”

– Matzke, N. and Gross, P., 2006, here.

“For biologists, then, the microevolution/macroevolution distinction is a matter of scale of analysis, and not some ill-defined level of evolutionary “newness.” Studies that examine evolution at a coarse scale of analysis are also macroevolutionary studies, because they are typically looking at multiple species – separate branches on the evolutionary tree. Evolution within a single twig on the tree, by contrast, is microevolution.”

– Matzke, N., and Gross, P. (2006). “Analyzing Critical Analysis: The Fallback Antievolutionist Strategy.” Chapter 2 of Not in Our Classrooms: Why Intelligent Design is Wrong for Our Schools. Scott, E., and Branch, G., eds., Beacon Press, pp. 49-50. Cited by Nick Matzke here.

“I was not prepared to find creationists . . . actually accepting the [peppered] moths as examples of small-scale evolution by natural selection! . . . That, to my mind, is tantamount to conceding the entire issue, for . . . there is utter continuity in evolutionary processes from the smallest scales (microevolution) up through the largest scales (macroevolution).”

– Eldredge, N. 2000. The Triumph of Evolution. New York: W.H. Freeman and Co. p. 119. (cf. pp. 62, 66, 76, 88). Cited by Richard Peachey here.

“… there is no justification for dismissing the selective and genetic mechanism responsible for the change from grey to black in [peppered] moths as incapable of producing new organs… there are no grounds for doubting that the mechanism of selection and mutation that has adaptively turned grey moths black in 100 years has been adequate to achieve evolutionary changes that have taken place during hundreds and thousands of millions of years.”

– De Beer, G. 1964. Atlas of Evolution. London: Nelson. pp. 93f. Cited by Richard Peachey here.

“Most sceptics about natural selection are prepared to accept that it can bring about minor changes like the dark coloration that has evolved in various species of moth since the industrial revolution. But, having accepted this, they then point out how small a change this is. … But… the moths only took a hundred years to make their change…. just think about the time involved.”

– Dawkins, R. 1986. The Blind Watchmaker. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 40. Cited by Richard Peachey here.

(b) Scientists who are UNDECIDED on whether macroevolution is explicable in terms of microevolution

“One of the oldest problems in evolutionary biology remains largely unsolved; Historically, the neo-Darwinian synthesizers stressed the predominance of micromutations in evolution, whereas others noted the similarities between some dramatic mutations and evolutionary transitions to argue for macromutationism.”

– Stern, David L. Perspective: Evolutionary Developmental Biology and the Problem of Variation, Evolution, 2000, 54, 1079-1091. A contribution from the University of Cambridge.

“A persistent debate in evolutionary biology is one over the continuity of microevolution and macroevolution – whether macroevolutionary trends are governed by the principles of microevolution.”

– Simons, Andrew M. The Continuity of Microevolution and Macroevolution Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 2002, 15, 688-701. A contribution from Carleton University.

“A long-standing issue in evolutionary biology is whether the processes observable in extant populations and species (microevolution) are sufficient to account for the larger-scale changes evident over longer periods of life’s history (macroevolution). Outsiders to this rich literature may be surprised that there is no consensus on this issue, and that strong viewpoints are held at both ends of the spectrum, with many undecided.”

– Carroll, Sean B. 2001 (Feb 8). Nature 409:669. Cited by Richard Peachey here.

“Most professional biologists today think of microevolution as evolution within species and of macroevolution as what happens over time to differentiate species or ‘higher’ groups of organisms (genera, families, etc.)….

“The reason I think creationists, and the public at large, are not well served by scientists in this case is because few evolutionary biologists talk to the public to begin with, and when they are confronted with the micro/macro question, they simply accuse creationists of making up such a distinction and move on. What they (we) should say is that there is indeed genuine disagreement among professional biologists about the meaningfulness of the concept, and even those who agree that there is something to it are still trying to figure out an explanation.”

– Massimo Pigliucci, “Is There Such a Thing as Macroevolution?” Skeptical Inquirer 31(2):18,19, March/April, 2007. Pigliucci is a prominent professor of evolutionary biology and philosophy.

(Cited by Richard Peachey here.)

(c) Scientific authorities who REJECT the view that macroevolution is merely an extrapolation of microevolution

“PaV asked:

Do the “engines of variation” provide sufficient variation to move beyond microevolution to macroevolution.”

“This is indeed the central question. One of the central tenets of the “modern synthesis of evolutionary biology” as celebrated in 1959 was the idea that macroevolution and microevolution were essentially the same process. That is, macroevolution was simply microevolution extrapolated over deep evolutionary time, using the same mechanisms and with essentially the same effects.

“A half century of research into macroevolution has shown that this is probably not the case. In particular, macroevolutionary events (such as the splitting of a single species into two or more, a process known as cladogenesis) do not necessarily take a long time at all. Indeed, in plants it can take as little as a single generation. We have observed the origin of new species of rose, primroses, trees, and all sorts of plants by genetic processes, such as allopolyploidy and autopolyploidy. Indeed, most of the cultivated roses so beloved of gardeners are new species of roses that originated spontaneously as the result of chromosomal rearrangements, which rose fanciers then exploited.

“The real problem, therefore, is explaining cladogenesis in animals. As Lynn Margulis has repeatedly pointed out, animals have a unique mechanism of sexual reproduction and development, one that apparently makes the kinds of chromosomal events that are common in plants very difficult in animals.

“However, she has proposed an alternative mechanism for cladogenesis in animals, based on the acquisition and fusion of genomes. Research into such mechanisms has only just begun, but has already been shown to explain the origin of eukaryotes via the fusion of disparate lines of prokaryotes, plus the origin of several species of animals and plants as the result of genome acquisition. As Lynn has been extraordinarily successful in the past in proposing testable mechanisms for macroevolutionary changes, I look forward to many more discoveries in this field.”

– MacNeill, Allen. comment on “We is Junk” article by PaV at Uncommon Descent, 2006.

“In other words, microevolution (i.e. natural selection, genetic drift, and other processes that happen anagenetically at the population level) and macroevolution (i.e. extinction/adaptive radiation, genetic innovation, and symbiosis that happen cladogenetically at the species level and above) are in many ways fundamentally different processes with fundamentally different mechanisms. Furthermore, for reasons beyond the scope of this thread, macroevolution is probably not mathematically modelable in the way that microevolution has historically been.”

– MacNeill, Allen. comment on “We is Junk” article by PaV at Uncommon Descent, 2006.

Abstract

“Arguments over macroevolution versus microevolution have waxed and waned through most of the twentieth century. Initially, paleontologists and other evolutionary biologists advanced a variety of non-Darwinian evolutionary processes as explanations for patterns found in the fossil record, emphasizing macroevolution as a source of morphologic novelty. Later, paleontologists, from Simpson to Gould, Stanley, and others, accepted the primacy of natural selection but argued that rapid speciation produced a discontinuity between micro- and macroevolution. This second phase emphasizes the sorting of innovations between species. Other discontinuities appear in the persistence of trends (differential success of species within clades), including species sorting, in the differential success between clades and in the origination and establishment of evolutionary novelties. These discontinuities impose a hierarchical structure to evolution and discredit any smooth extrapolation from allelic substitution to large-scale evolutionary patterns. Recent developments in comparative developmental biology suggest a need to reconsider the possibility that some macroevolutionary discontinuites may be associated with the origination of evolutionary innovation. The attractiveness of macroevolution reflects the exhaustive documentation of large-scale patterns which reveal a richness to evolution unexplained by microevolution. If the goal of evolutionary biology is to understand the history of life, rather than simply document experimental analysis of evolution, studies from paleontology, phylogenetics, developmental biology, and other fields demand the deeper view provided by macroevolution.”

– Erwin, Douglas H. Macroevolution is more than repeated rounds of microevolution. Evolution and Development, 2000, Mar-Apr;2(2):78-84.

“… large-scale evolutionary phenomena cannot be understood solely on the basis of extrapolation from processes observed at the level of modern populations and species… The most conspicuous event in metazoan evolution was the dramatic origin of major new structures and body plans documented by the Cambrian explosion… The extreme speed of anatomical change and adaptive radiation during this brief time period requires explanations that go beyond those proposed for the evolution of species within the modern biota… This explosive evolution of phyla with diverse body plans is certainly not explicable by extrapolation from the processes and rates of evolution observed in modern species…”

– Carroll, Robert. 2000 (Jan). Trends in Ecology and Evolution 15(1):27f. Cited by Richard Peachey here.

“… biologists have documented a veritable glut of cases for rapid and eminently measurable evolution on timescales of years and decades… to be visible at all over so short a span, evolution must be far too rapid (and transient) to serve as the basis for major transformations in geological time. Hence, the ‘paradox of the visibly irrelevant’ – or, if you can see it at all, it’s too fast to matter in the long run… These shortest-term studies are elegant and important, but they cannot represent the general mode for building patterns in the history of life… Thus, if we can measure it at all (in a few years), it is too powerful to be the stuff of life’s history… [Widely publicized cases such as beak size changes in ‘Darwin’s finches’] represent transient and momentary blips and fillips that ‘flesh out’ the rich history of lineages in stasis, not the atoms of substantial and steadily accumulated evolutionary trends… One scale doesn’t translate into another.”

– Gould, Stephen J. 1998 (Jan). Natural History 106(11):12, 14, 64. Cited by Richard Peachey here.

“If macroevolution is, as I believe, mainly a story of the differential success of certain kinds of species and, if most species change little in the phyletic mode during the course of their existence (Gould and Eldredge, 1977), then microevolutionary change within populations is not the stuff (by extrapolation) of major transformations.”

– Gould, Stephen J., in Ernst Mayr and William B. Provine, The Evolutionary Synthesis: Perspectives on the Unification of Biology (Harvard University Press paperback, 1998; originally published in 1980), p. 170. Cited by Richard Peachey here.

“A wide spectrum of researchers – ranging from geologists and paleontologists, through ecologists and population geneticists, to embryologists and molecular biologists – gathered at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History under the simple conference title: Macroevolution. Their task was to consider the mechanisms that underlie the origin of species and the evolutionary relationship between species… The central question of the Chicago conference was whether the mechanisms underlying microevolution can be extrapolated to explain the phenomena of macroevolution. At the risk of doing violence to the positions of some of the people at the meeting, the answer can be given as a clear, No.”

– Lewin, R. 1980 (Nov 21). Science 210:883. Cited by Richard Peachey here.

“What you are trying to argue, in a very confused way, is that you have some kind of problem with the statement that macroevolution is “just” microevolution over large amounts of time. Well, lots of people have a problem with this claim, including me – it’s rather like saying microeconomics can be simply scaled up to produce macroeconomics. Or that the ecology of a single field experiment can be scaled up to explain the macroecology of the Amazonian rainforest.”

– Matzke, Nicholas J., here.

Has anyone else noticed that Matzke falls into camps (a) and (c)?