It is often claimed that methodological naturalism is a principle which defines the scope of the scientific enterprise. Today’s post is about thirty-one famous scientists throughout history who openly flouted this principle, in their scientific writings, by putting forward arguments for a supernatural Deity.

The term “methodological naturalism” is defined variously in the literature. All authorities agree, however, that if you put forward scientific arguments for the existence of a supernatural Deity, then you are violating the principle of methodological naturalism. The 31 scientists whom I’ve listed below all did just that. I’ve supplied copious documentation, to satisfy the inquiries of skeptical readers.

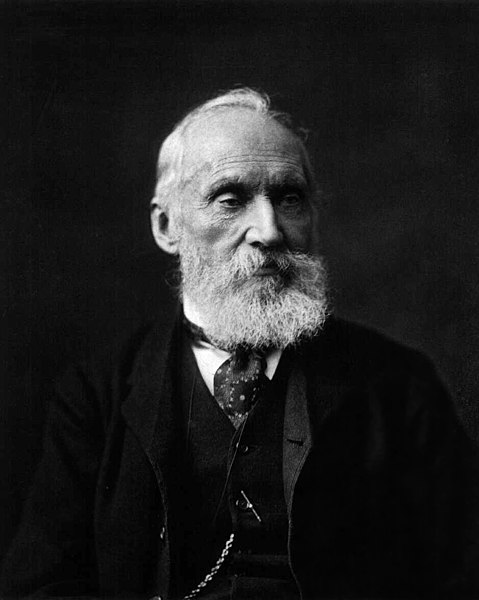

My own researches have led me to the conclusion that the principle of methodological naturalism is not a time-honored principle of science, but that it is of comparatively recent origin, first making its appearance in the scientific realm in the 1830s (about the time when the newly minted term “scientist” began to replace the older term, “natural philosopher”), and not securing general acceptance in the scientific arena until the 1870s. Even then, there were a few hold-outs, like Lord Kelvin, who publicly argued for the existence of a Creator in a speech given in 1903.

Acknowledgments

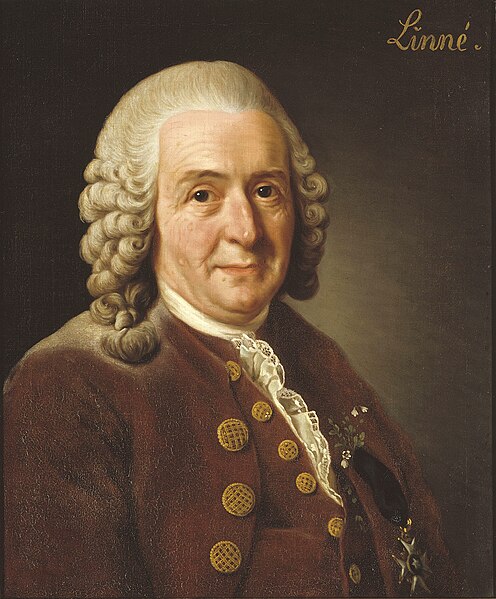

I have made use of a variety of different sources in my biographical research, but I would like to single out the following for special mention: THE WORLD’S GREATEST CREATION SCIENTISTS From Y1K to Y2K by David Coppedge and Creation scientists and other biographies of interest by Answers in Genesis, as well as various online articles by the Institute for Creation Research. (I should add that although I am a believer in an old universe and in common descent, I am quite happy to draw upon the research of other believers in a Designer of Nature, whatever their religious persuasion, if I am convinced of the scholarly merits of their research.) I would also like to thank Stephen Snobelen, Assistant Professor in the History of Science and Technology at the University of King’s College, Halifax, Nova Scotia, for his valuable work on Newton, and Carl Frangsmyr, Magdalena Hydman and Ragnar Insulander, of Uppsala University, for their valuable biographical research on Linnaeus. I’d like to thank Michael Flannery for his research into the life of Alfred Russel Wallace, and Ian Hutchison for his research on Maxwell’s religious views

(1) Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543), the founder of modern astronomy.

Who was he and what was he famous for?

Nicolaus Copernicus was the first person to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology which displaced the Earth from the center of the universe. He was also a mathematician, astronomer, jurist with a doctorate in law, physician, quadrilingual polyglot, classics scholar, translator, artist, Catholic cleric, governor, diplomat and economist.

How did he violate the principle of methodological naturalism?

In his scientific writings, Copernicus referred to God as “the Artificer of all things.” The motivation for Copernicus proposing his heliocentric hypothesis in the first place was a theological one. In his great treatise on astronomy, De revolutionibus orbium caelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, 1543), Copernicus voices his conviction that anyone who diligently contemplates the movements of the celestial bodies will be led thereby to a knowledge of God. In Chapter 8 of the same work, Copernicus even puts forward theological arguments in favor of his scientific theory that the Earth rotates on its axis once a day.

Where’s the evidence?

In the Preface to his work De revolutionibus orbium caelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, 1543), Copernicus explains that the motivation for his heliocentric hypothesis was theological. He believed that a universe that had been created by God for our sake must be comprehensible to the human mind. He states that he was forced to revive the long-forgotten heliocentric hypothesis, because it alone could yield knowledge of the movements of the heavenly bodies with the desired accuracy:

For a long time, then, I reflected on this confusion in the astronomical traditions concerning the derivation of the motions of the universe’s spheres. I began to be annoyed that the movements of the world machine, created for our sake by the best and most systematic Artisan of all, were not understood with greater certainty by the philosophers, who otherwise examined so precisely the most insignificant trifles of this world. For this reason I undertook the task of rereading the works of all the philosophers which I could obtain to learn whether anyone had ever proposed other motions of the universe’s spheres than those expounded by the teachers of astronomy in the schools. And in fact first I found in Cicero that Hicetas supposed the earth to move. Later I also discovered in Plutarch that certain others were of this opinion.

In the Introduction to his work De revolutionibus orbium caelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, 1543), Copernicus expressed his conviction that anyone who diligently contemplates the order displayed in the movements of the celestial bodies will thereby come to admire “the Artificer of all things”:

“For who, after applying himself to things which he sees established in the best order and directed by Divine ruling, would not through diligent contemplation of them and through a certain habituation be awakened to that which is best and would not admire the Artificer of all things, in Whom is all happiness and every good? For the divine Psalmist surely did not say gratuitously that he took pleasure in the workings of God and rejoiced in the works of His hands, unless by means of these things as by some sort of vehicle we are transported to the contemplation of the highest good.” (Copernicus, Nicolaus, On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, Thorn: Societas Copernicana, 1873, pp. 10-11).

In the following paragraph, Copernicus refers to astronomy as a “divine rather than human science” and favorably quotes the opinion of Plato, who was inclined to think that no-one lacking a knowledge of the heavenly bodies could be called godlike:

The great benefit and adornment which this art [astronomy – VJT] confers on the commonwealth (not to mention the countless advantages to individuals) are most excellently observed by Plato. In the Laws, Book VII, he thinks that it should be cultivated chiefly because by dividing time into groups of days as months and years, it would keep the state alert and attentive to the festivals and sacrifices. Whoever denies its necessity for the teacher of any branch of higher learning is thinking foolishly, according to Plato. In his opinion it is highly unlikely that anyone lacking the requisite knowledge of the sun, moon, and other heavenly bodies can become and be called godlike.

However, this divine rather than human science, which investigates the loftiest subjects, is not free from perplexities.

(Nicholas Copernicus, De Revolutionibus (On the Revolutions), 1543. Source: Translation and Commentary by Edward Rosen, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London. Adapted from Dartmouth College, MATC, Online reader.)

At the beginning of the Introduction to his great work, Copernicus even defines the science of astronomy in theological terms, as “the discipline which deals with the universe’s divine revolutions, the asters’ motions, sizes, distances, risings and settings, as well as the causes of the other phenomena in the sky, and which, in short, explains its whole appearance.” (Nicholas Copernicus, De Revolutionibus (On the Revolutions), 1543. Source: Translation and Commentary by Edward Rosen, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London. Adapted from Dartmouth College, MATC, Online reader.)

In Chapter 8 of his De revolutionibus orbium caelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, 1543), Copernicus even adduces theological arguments in favor of the stability of the universe and the daily rotation of the Earth, after listing several scientific arguments for these ideas:

As a quality, moreover, immobility is deemed nobler and more divine than change and instability, which are therefore better suited to the earth than to the universe… You see, then, that all these arguments make it more likely that the earth moves than that it is at rest. This is especially true of the daily rotation, as particularly appropriate to the earth. This is enough, in my opinion, about the first part of the question.”

(Nicholas Copernicus, De Revolutionibus (On the Revolutions), 1543. Source: Translation and Commentary by Edward Rosen, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London. Adapted from Dartmouth College, MATC, Online reader.)

Let us review the evidence. The motivation for Copernicus proposing his heliocentric hypothesis in the first place was a theological one. In his great treatise on astronomy, Copernicus voices his conviction that anyone who diligently contemplates the movements of the celestial bodies will be led thereby to a knowledge of God. He refers to astronomy as a “divine rather than human science,” and he approvingly quotes Plato’s statement that no-one who lacks a knowledge of the heavenly bodies can be called godlike. He even defines the science of astronomy in theological terms, as “the discipline which deals with the universe’s divine revolutions.” In Chapter 8 of the same work, Copernicus even puts forward theological arguments in favor of his scientific theory that the Earth rotates on its axis once a day. Can anyone describe such a man as a methodological naturalist?

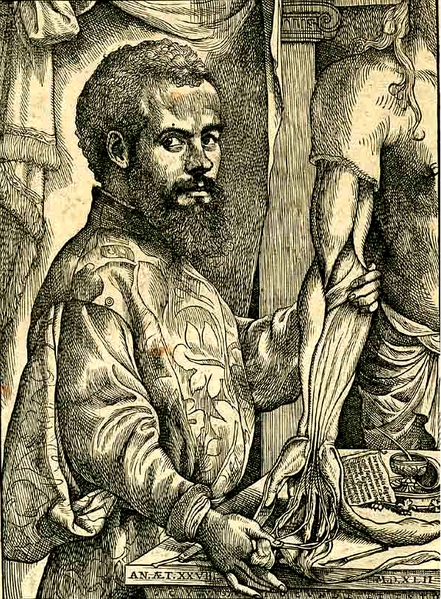

(2) Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), the founder of modern anatomy.

Who was he and what was he famous for?

Andreas Vesalius was the author of De humani corporis fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body). He is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy.

How did he violate the principle of methodological naturalism?

In his scientific writings, Vesalius repeatedly referred to God, to the Creator, to the Founder of things (Conditor rerum), and to the Great Artisan of things (or Opifex). He also declared that the construction of the human body can be used to “argue for the admirable industry of the immense Creator.” His understanding of human anatomy was thoroughly teleological: he believed that God had designed each organ of the human body for a specific purpose.

Where’s the evidence?

(a) In his scientific writings, Vesalius frequently referred to God, the Creator, the Founder of things, and the Great Artisan

The following quotes are taken from an essay by Nancy G. Siraisi, entitled, Vesalius and the reading of Galen’s teleology (Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 50, No. 1, Spring 1997, pp. 1-37):

In the Fabrica, references to Natura [Nature – VJT] – always capitalized and followed by an active verb – must run into the hundreds. There is also a substantial group of references to the Opifex [Artisan – VJT] of things and a few to the Founder of things (Conditor rerum), to the Creator, or to God. For any Christian author, the terms conditor, creator, deus and probably opifex presumably all refer to the Christian God…. A few examples follow:

If only contemplating in the construction of mankind you consider in this way, you will grasp things [about the orbit of the eye] which, although they may not be greatly conducive to the art of medicine, argue for the admirable industry of the immense Creator.Rightly to be praised is the immense Opifex of things whom we think bestowed on the teeth alone of the rest of the bones a noteworthy faculty of feeling.

[I]t behooved the Opifex of things to pay attention to four particular needs when constructing the thorax, namely voice, respiration and the size of the heart and lung.

But the joints show how skilfully Nature constructed these things for obeying the motions which we endeavor [to make] with the thighs.

For unless the joints of the bones and cartilages were held together with ligaments nothing would prevent the bones or the cartilages from being dislocated in the course of some movement or other … Lest that happen God the highest opifex of things surrounded the bones of the joints and cartilages with ligaments, strong indeed but also capable of considerable stretching. Greatly to be wondered at is the industry of the Creator.

Therefore Nature by a certain marvelous artifice produced two muscles … placing one in the greater angle of the eye, the other in the lesser.

[The ligaments of the first and second sections of the cervical vertebrae] abundantly demonstrate the industry of Nature to the spectator however perfunctorily they are narrated. When therefor it was necessary to link the first cervical vertebra to the head, Nature rightly created a strong and robust ligament… But lest [the vertebra] should be dislocated … the Opifex of things created another ligament.

Nature neither carelessly nor negligently constructed the oblique course of this tendon [of the foot].

But rather, the admirable industry of Nature here should come to be considered who enginerred all those things thus divinely, nor constructed anything in the intestines unless for the highest usefulness … And considering these purposes indeed she most artfully crafted the intestines.

[W]e will rightly praise the care of the highest Opifex of things who constructed the rough artery [that is, the trachea] as simultaneously a convenient organ of respiration and voice. And he showed such great artifice in the construction of the larynx that it can be closed now more, now less.

[T]hese fibers [of the dura mater of the brain] that Nature has fastened surpass in ingenuity the cords by which Vulcan bound Mars to Venus, for they support while they tether.

The issue here is not to determine how many of these statements Vesalius took from Galen and how many he issued on his own account. Rather, the point I wish to make is simply that language of this kind is pervasive in the Fabrica. It is impossible to read more than a few pages without coming across examples. It therefore seems that it deserves to be taken seriously.

(Siraisi, 1997, pages 14-17.)

(b) Vesalius maintained that knowledge of human anatomy could lead to a deeper knowledge of God

In her essay, Vesalius and the reading of Galen’s teleology, which I quoted above, Siraisi attempts to explain the prevalence of teleological language in the writings of Vesalius. She contends that it sprang from his deep-seated conviction that knowledge of anatomy enables human beings to partake of the wisdom of God, their Creator:

… Vesalius repeatedly emphasized the role of his own superior anatomical skill in “exposing with certainty one skilful contrivance of Nature after another.” Thus, by providing accurate descriptions of structure, a good anatomist uncovers hitherto unknown or misinterpreted instances of Nature’s ingenuity. But once such descriptions have been made available they constitute self-evident inducements to appreciation of Nature’s skill and praise of the Creator. It is this self-evident quality that makes it possible to compress or eliminate longwinded generalizations upon the subject. (Siraisi, 1997, p. 19.)

[P]ositive moralizing themes that centered, like the example quoted from Massa above, on the idea of the human body as an outstanding example of God’s handiwork, are also frequent in sixteenth century rhetoric about anatomy. Thus Guinter of Andernach opined not only that God had made nothing better or more wonderful in the world than the harmony of the human body, but also that knowledge of the body “alone made men prudent and like gods.” When Vesalius himself characterized anatomy in his preface as “that most delightful (iucundissima) knowledge of man attesting to the wisdom of the immense Founder of things (Conditor rerum),” he was speaking the language of positive moralization as well as expressing a personal enthusiasm. (Siraisi, 1997, pp. 21-22.)

Galen, broader Renaissance philosophical currents, and the lack of any non-teleological framework for explaining biology all combined to ensure that his detailed investigations of human anatomy would strongly reinforce in him the fundamental conviction that every detail of anatomical structure revealed the forethought, ingenuity and skill of Nature, that is, ultimately of God. (Siraisi, 1997, p. 30.)

An additional reason for the wealth of paeans to the Creator lay in Vesalius’ conviction that God was not properly praised by incorrect depictions of His handiwork, such as were found in the writings of Galen. Hence, correct descriptions of human anatomy provided additional reasons to praise the ingenuity of the Creator:

In the new anatomy, at least ideally and most of the time, claims about Nature’s ingenuity were to be tied to accurate accounts of details of human structure. (Siraisi, 1997, p. 30.)

This brings me to my next point: one of the reasons why Vesalius cared so passionately about describing the human body correctly was that he considered incorrect descriptions of God’s handiwork to constitute a form of blasphemy against the Creator. Hence his insistence on getting it right.

(c) Vesalius declared in his medical writings that we reverence God best by describing His handiwork accurately

In his book, Andreas Vesalius of Brussels (University of California Press, 1964), Charles Donald O’Malley cites a passage from Vesalius’ on the human brain, in which he declares that poor anatomical descriptions (such as were found in the writings of his contemporaries) constitute a form of impiety towards God, and that we reverence God best by describing His handiwork accurately:

Book VII provides a description of the anatomy of the brain accompanied by a series of detailed illustrations revealing the successive steps in its dissection. Until at least the end of the fifteenth century knowledge of the brain had remained medieval, based not so much upon Galen’s doctrines as upon a debased tradition, a situation that permitted Vesalius to introduce his discussion with a notably severe criticism:

Who, immortal God, will not be amazed at that crowd of philosophers, and let me add, theologians of today who, detracting so falsely from the divine and wholly admirable contrivance of the human brain, frivolously, like Prometheans, and with greatest impiety toward the Creator, fabricate some sort of brain from their dreams and refuse to observe that which the Creator with incredible providence shaped for the uses of the body. They parade their monstrosity, shamelessly deluding those tender minds that they instruct.

(O’Malley, 1964, p. 178)

But there’s more. Vesalius also argued that each part of the human body was the human body was skilfully designed by God to accomplish its designated purpose(s).

(d) Intelligent Design arguments in the medical writings of Vesalius

In his book, Andreas Vesalius of Brussels (University of California Press, 1964), Charles Donald O’Malley also addresses the frequent teleological references in Vesalius’ Fabrica. On page 155, O’Malley provides an example of a typical teleological argument in the anatomical writings of Vesalius. The argument contains an explicit reference to the Mind of the Intelligent Creator of Nature. In this passage, Vesalius argues that God had a special reason for making the human back in the way He did:

Chapter XIV opens with a further teleological argument:

Quite properly nature, the parent of everything, fashioned man’s back in the form of keel and foundation. In fact, it is through the support of the back that we are able to walk upright and stand erect. However, nature gave man a back not only for this purpose, but as she has made various uses of other single members she has constructed, so here too she has demonstrated her industry.First, she carved out a foramen in all the vertebrae at the posterior part of their bodies, so preparing a passage suitable for the descent of the dorsal marrow [i.e, spinal cord] through them. Second, she did not construct the entire back out of unorganized and simple bone. This might have been preferable for stability and for the safety of the dorsal marrow, since the back could not be dislocated, destroyed or distorted unless it had a number of joints. Indeed, if the Creator had in mind only the ability to withstand injury and had no other or more worthy goal in the structure of the organs, then the back would have been created as unorganized and simple. If anyone constructs an animal of stone or wood, he makes the back as a single continuous part, but since man must bend his back and stand erect it was better not to make it entirely from a single bone. On the contrary, since man must perform many different motions with the aid of his back it was better that it be constructed from many bones, even though in this way it was rendered more liable to injury.

(O’Malley, 1964, p. 155)

I’ll let my readers be the judge. Vesalius was a man who, with Copernicus, could be described as a co-founder (along with Copernicus) of the Scientific Revolution. This great thinker’s medical writings abound in references to to God, to the Creator, to the Founder of things, and to the Great Artisan. Vesalius even declares that a proper knowledge of anatomy makes us godlike, and reproaches those who make incorrect assertions about human anatomy with impiety. Finally, he argues that God did an excellent job in the way He constructed the various parts of the human body, including the human back. In other words, he was an Intelligent Design proponent. Is this a man whom you would describe as a methodological naturalist?

(3) Francis Bacon (1561-1626), the author of an inductive methodology for scientific enquiry which bears his name (the Baconian method) and which had a lasting influence on the course of the Scientific Revolution.

Who was he and what was he famous for?

Francis Bacon was the author of an inductive methodology for scientific enquiry which bears his name (the Baconian method) and which had a lasting influence on the course of the Scientific Revolution.

How did he violate the principle of methodological naturalism?

Bacon clearly stated in his writings that an investigation of the natural world could lead scientists to a sure knowledge of God. But if he reasoned in this way, then he cannot have believed, as many modern philosophers of science falsely allege, that science can only yield natural knowledge, and that the supernatural is barred to scientific enquiry. In other words, Bacon was not a methodological naturalist.

Bacon also referred to natural philosophy (science) as the “most faithful handmaid” of religion.

Where’s the evidence?

(a) Bacon maintained that the existence of God is obvious, and that the human mind is capable of inferring the existence of a supernatural Deity even from ordinary natural phenomena

In his famous essay Of Atheism, Bacon treats the existence of God as an obvious fact – a fact so obvious from God’s ordinary works (which are found in Nature) that it needs no miracle to confirm it.

It is important to understand Bacon’s meaning correctly here. Bacon is not rejecting the existence of miracles; after all, he was a Christian, as his own personal Confession of Faith clearly shows, and he acknowledges in his confession of faith that on rare occasions, “God doth transcend the law of nature by miracles,” as for instance when Jesus Christ “took flesh of the Virgin Mary.” Rather, what Bacon is saying is in his essay Of Atheism is that the human mind is capable of inferring the existence of a supernatural Deity even from ordinary natural phenomena. The human mind has a lazy tendency to cease its rational enquiry into the explanation of a phenomenon when it discovers a natural second[ary] cause. Viewed in isolation from other causes (i.e. “scattered,” as Bacon puts it), secondary causes at first appear sufficient to account for phenomena, and a shallow human mind may “rest in them, and go no further.” However, when the human mind beholds the ensemble or “chain” of secondary causes in Nature, “confederate and linked together,” it cannot help but conclude that there is a God – or as Bacon puts it, “it must needs fly to Providence and Deity.”

Bacon then goes on to express incredulity at the absurd idea that an infinite number of scattered atoms (“seeds unplaced”) could generate the order and beauty we find in the cosmos:

I had rather believe all the fables in the Legend, and the Talmud, and the Alcoran, than that this universal frame is without a mind. And therefore, God never wrought miracle, to convince atheism, because his ordinary works convince it. It is true, that a little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism; but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion. For while the mind of man looketh upon second causes scattered, it may sometimes rest in them, and go no further; but when it beholdeth the chain of them, confederate and linked together, it must needs fly to Providence and Deity. Nay, even that school which is most accused of atheism doth most demonstrate religion; that is, the school of Leucippus and Democritus and Epicurus. For it is a thousand times more credible, that four mutable elements, and one immutable fifth essence, duly and eternally placed, need no God, than that an army of infinite small portions, or seeds unplaced, should have produced this order and beauty, without a divine marshal.

This is an Intelligent Design argument, in broad outline, and it is totally incompatible with methodological naturalism. Bacon treats the existence of God as an evident fact which needs no miraculous sign to confirm it; but according to methodological naturalism, scientists can only infer natural causes for natural phenomena. Bacon, however, does not hesitate to go beyond secondary causes and “fly to Providence and Deity” when he beholds the chain of secondary causes in Nature.

(b) Bacon referred to science (natural philosophy) as the “most faithful handmaid” of religion

Bacon’s supernaturalism becomes even more evident when one examines his classic work, The New Organon (1620). In chapter LXXXIX, Bacon talks about the obstacles that natural philosophy has had to contend with in the past – in particular, “superstition, and the blind and immoderate zeal of religion.” Bacon cites historical instances in which scientists investigating the causes for natural phenomena were accused of impiety by the ancient Greeks, as well as some of the early Christian Fathers. He then criticizes what he regards as the unfortunate incorporation of Aristotle’s philosophy into the Christian religion by medieval schoolmen, which impeded the investigation of natural phenomena. Later on, other theologians made the fatal mistake of mingling the divine and the human by attempting to deduce the Divine truths of the Christian faith from human philosophical principles. Finally, Bacon attacks the simple-minded attitude of some clerics (or divines) who feared a no-holds-barred philosophical investigation of the natural world. It is worth recalling, when reading the following passage, that science was referred to as “natural philosophy”, in Bacon’s time:

Lastly, you will find that by the simpleness of certain divines, access to any philosophy, however pure, is well-nigh closed. Some are weakly afraid lest a deeper search into nature should transgress the permitted limits of sober-mindedness, wrongfully wresting and transferring what is said in Holy Writ against those who pry into sacred mysteries, to the hidden things of nature, which are barred by no prohibition. Others with more subtlety surmise and reflect that if second causes are unknown everything can more readily be referred to the divine hand and rod, a point in which they think religion greatly concerned — which is in fact nothing else but to seek to gratify God with a lie. Others fear from past example that movements and changes in philosophy will end in assaults on religion. And others again appear apprehensive that in the investigation of nature something may be found to subvert or at least shake the authority of religion, especially with the unlearned. But these two last fears seem to me to savor utterly of carnal wisdom; as if men in the recesses and secret thought of their hearts doubted and distrusted the strength of religion and the empire of faith over the sense, and therefore feared that the investigation of truth in nature might be dangerous to them. But if the matter be truly considered, natural philosophy is, after the word of God, at once the surest medicine against superstition and the most approved nourishment for faith, and therefore she is rightly given to religion as her most faithful handmaid, since the one displays the will of God, the other his power. For he did not err who said, “Ye err in that ye know not the Scriptures and the power of God,” thus coupling and blending in an indissoluble bond information concerning his will and meditation concerning his power. Meanwhile it is not surprising if the growth of natural philosophy is checked when religion, the thing which has most power over men’s minds, has by the simpleness and incautious zeal of certain persons been drawn to take part against her.

Notice that Bacon here refers to natural philosophy or science as the “most faithful handmaid” of religion, insofar as it reveals the power of God. Notice also that Bacon regards religion and natural philosophy as coupled and blended “in an indissoluble bond.” For Bacon, there was no wall of separation between the two, and he would have been puzzled by the suggestion that natural philosophy is limited to investigating the secondary causes of phenomena.

(4) Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), the Father of modern astronomy and the father of modern physics.

Who was he and what was he famous for?

Galileo Galilei was the Father of modern astronomy and the father of modern physics.

How did he violate the principle of methodological naturalism?

Galileo affirmed the reality of miracles in his writings. He also wrote that birds were beautifully designed for flight, and that fish were admirably designed for swimming in water. That’s an Intelligent Design-style argument. Finally, he believed that the human mind was not the product of Nature, but must have been specially created by God.

Where’s the evidence?

Was Galileo a methodological naturalist? Ronald Numbers (2003) seems to think so. He quotes Galileo in support of a claim that the laws of Nature are never broken. As we shall see, Galileo says nothing of the sort. Before I do so, however, I would like to clear up a number of popular misconceptions.

It needs to be kept in mind that Galileo remained a devout Catholic all his life. His famous aphorism, “The Bible was written to show us how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go,” was not intended as a criticism of the Church, but was actually a citation from the writings of a cardinal of the Catholic Church, Cardinal Baronius, who made this statement in 1598, long before Galileo ever looked through a telescope (Stillman Drake, Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo, Doubleday Anchor Books, 1957, p. 136). Indeed, Pope Urban VIII sent his special blessing to Galileo as he was dying. After his death, Galileo was interred not only in consecrated ground, but within the church of Santa Croce at Florence.

There are four grounds for denying that Galileo could have been a methodological naturalist.

(a) Galileo believed in Nature miracles, such as the Biblical miracle of Joshua

“Even if Galileo was a Catholic, those were his personal views,” you may object. “They have absolutely no relevance to his work as a scientist.” But wait, there’s more! Galileo believed in miracles, too. That means that he could not have believed that the laws of Nature are never violated, as Ronald Numbers claims. Take a look at his Letter to Madame Christina of Lorraine, Grand Duchess of Tuscany: Concerning the Use of Biblical Quotations in Matters of Science (1615). In his letter, Galileo discusses the Biblical miracle in which Joshua commanded the Sun to stand still. What is interesting is that Galileo, the father of modern science, expressly affirms the reality of this miracle. The only point on which he differs from his Christian contemporaries is in his explanation of the mechanics of the miracle:

The sun, then, being the font of light and the source of motion, when God willed that at Joshua’s command the whole system of the world should rest and should remain for many hours in the same state, it sufficed to make the sun stand still. Upon its stopping all the other revolutions ceased; the earth, the moon, and the sun remained in the same arrangement as before, as did all the planets; nor in all that time did day decline towards night, for day was miraculously prolonged. And in this manner, by the stopping of the sun, without altering or in the least disturbing the other aspects and mutual positions of the stars, the day could be lengthened on earth — which agrees exquisitely with the literal sense of the sacred text.

So the father of modern science believed in miracles – and not just private little miracles, but big, public spectacles that everyone could see, and whose occurrence was a matter of public record (Joshua 10:12-14). So much for Galileo’s alleged methodological naturalism.

(b) How Ronald Numbers misreads Galileo on the laws of Nature

Ronald Numbers completely overlooks this point, in his discussion of Galileo. What’s more, he completely misinterprets Galileo, even making him out to be a disbeliever in miracles:

The Italian Catholic Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), one of the foremost promoters of the new philosophy, insisted that nature “never violates the terms of the laws imposed upon her.” (Numbers, 2003, p. 267)

The selective quotation from Galileo is taken from the letter to Madame Christina of Lorraine, Grand Duchess of Tuscany, which I quoted from above. When we consider that in the same letter, Galileo expressly affirms the reality of the miracle of the sun standing still, it is obvious that Galileo cannot have intended to say that the laws of Nature are never broken, as Numbers mistakenly construes him as saying.

What is Galileo saying in the passage selectively quoted by Numbers? He is saying that Nature is obedient. Matter, in his mechanical view of Nature, is inert and passive, and does what it is told. A body will react in a fixed way to whatever forces are applied to it. But in the passage cited by Numbers, Galileo is not concerned with the question of whether those forces are natural forces, pushing and pulling other particles, or supernatural forces (i.e. the will of God, moving matter). Nowhere does Galileo assert that that Nature is a causally closed system; in any case, as we have seen above, belief in the causal closure of Nature was not common until the mid-nineteenth century. Instead, what Galileo is arguing is that Nature cannot fail to respond to the forces acting on it. There can be no question of Nature rebelling against the command of these forces; for Nature is unable to defy any command imposed upon her. Hence, if sense-experience tells us that something happened, we should not doubt for a moment that it actually did, for Nature, which causes our sense-experiences, cannot deceive. The thinking here is the same as in the old adage, “The camera does not lie.” As Galileo puts it:

But Nature, on the other hand, is inexorable and immutable; she never transgresses the laws imposed upon her, or cares a whit whether her abstruse reasons and methods of operation are understandable to men. For that reason it appears that nothing physical which sense-experience sets before our eyes, or which necessary demonstrations prove to us, ought to be called in question (much less condemned) upon the testimony of biblical passages which may have some different meaning beneath their words.

Galileo then goes on to discuss the miracle of Joshua. Not for a moment does he contest its reality. The only point at issue is whether the Sun stopped moving, or the Earth.

(c) Galileo was an Intelligent Design advocate

It gets even worse for Numbers. It turns out that Galileo was something of an Intelligent Design theorist. I am deeply indebted to Michael Caputo for the following quotes, and I would like to express my sincere thanks to him, for his valuable research.

Galileo’s observations and meditations on God’s wonders led him to conclude: “To me the works of nature and of God are miraculous.” (Brunetti, F. Opere di Galileo Galilei. Torino: Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese, 1964, p. 506.)

Poetic license, you say? I haven’t finished yet; there’s more. Galileo often mused on what he saw as the stunning manifestations of God’s creative wisdom. He was particularly impressed with birds and their ideal design for flight, and with fish and their perfect design for swimming in water:

God could have made birds with bones of massive gold, with veins full of molten silver, with flesh heavier than lead and with tiny wings… He could have made fish heavier than lead, and thus twelve times heavier than water, but He has wished to make the former of bone, flesh, and feathers that are light enough, and the latter as heavier than water, to teach us that He rejoices in simplicity and facility. (Sobel, Dava, Galileo’s Daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith, and Love. Toronto: Viking Press, 1999, p. 99.)

So according to Galileo, God not only personally designed fish, but He also designed the bones, veins, flesh and feathers of birds, in exquisite detail.

(d) Galileo held that the human mind had been created by God, and he believed that God spoke to him

To add insult to injury, it appears that Galileo, “the father of modern science,” was what the Darwinian philosopher Daniel Dennett disparagingly describes as a “mind-creationist”: he believed that the human mind was not the product of Nature, but must have been specially created by God. The human mind was, according to Galileo, one the greatest of God’s achievements: “When I consider what marvelous things men have understood, what he has inquired into and contrived, I know only too clearly that the human mind is a work of God, and one of the most excellent.” Yet the potential of the human mind “… is separated from the Divine knowledge by an infinite interval.” (Poupard, Cardinal Paul. Galileo Galilei. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1983, p. 101.)

Galileo saw himself as a man privileged by God. He believed that God, in His mercy, occasionally deigns to reveal a new insight to some chosen individual, thus augmenting the stock of knowledge revealed to humanity: “One must not doubt the possibility that the Divine Goodness at times may choose to inspire a ray of His immense knowledge in low and high intellects, when they are adorned with sincere and holy zeal.” (Chiari, A. Galileo Galilei, Scritti Letterari. Florence: Felice Le Monnier, 1970, p. 545.) Galileo saw himself as the recipient of great truths that were previously known only to God, and he expressed his gratitude to God for being the first to experience these revelations: “I render infinite thanks to God, for being so kind as to make me alone the first observer of marvels kept hidden in obscurity for all previous centuries.” (Sobel, Dava, Galileo’s Daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith, and Love. Toronto: Viking Press, 1999, p. 6.)

Seer. Supernaturalist. Miracle believer. Intelligent Design theorist. Mind creationist. This is the secularists’ hero, Galileo Galilei. And he was a great scientist, too. I hope, that they will be gracious enough to allow Louisiana high school students the right to freely hold and publicly defend the same views as those held by the father of modern science.

(5) Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), best known for his three laws of planetary motion.

Who was he and what was he famous for?

Kepler was a German mathematician and astronomer, who is best known for his three laws of planetary motion.

How did he violate the principle of methodological naturalism?

Kepler wisely refused to treat the Bible as a science textbook, maintaining that it was never meant to be used in such a fashion. However, he explicitly incorporated religious arguments and reasoning into his scientific works, arguing that because the universe was designed by an intelligent Creator, it should function in accordance with some mathematical pattern. That’s theological reasoning, and it played a vital part in Kepler’s scientific discoveries.

Where’s the evidence?

(a) Kepler’s principal axiom, when doing science, was that everything in the world was created by God according to a plan

Let me begin by quoting from a biography, Kepler, by Max Caspar, translated and edited by Clarise Doris Hellman (Dover Publications, 1993, p. 62):

Nothing in the world was created by God without a plan; this was Kepler’s principal axiom. His undertaking was no less than to discover this plan for creation, to think the thoughts of God over again, because he was convinced that “just like a human architect, God has approached the foundation of the world according to order and rule and so measured out everything that one might suppose that architecture did not take Nature as a model but rather that God had looked upon the manner of building the coming [ED. NOTE: “about to be created”] human.”

But don’t take my word for i. Just take a look at chapters four and ten from Kepler’s Harmonices Mundi (Harmonies of the World) (1619), the scientific treatise in which he announced the discovery of his famous third law of planetary motion. If Kepler had been a methodological naturalist, there’s no way he could have written those chapters.

(b) Kepler used theological arguments in his scientific works

Recent historians of science have highlighted the theological underpinnings of Kepler’s astronomical arguments. In an article entitled, “Theological Foundations of Kepler’s Astronomy” (Osiris 16: Science in Theistic Contexts. University of Chicago Press, 2001, pp. 88-113), Professors Peter Barker and Bernard Goldstein demonstrate that Kepler incorporated religious arguments and reasoning into his work. Ms. Genevieve Gebhart takes their argument further in her award-winning essay, Convinced by Comparison: Lutheran Doctrine and Neoplatonic Conviction in Kepler’s Theory of Light (intersections 11, no. 1 (2010): 44-52). She illustrates how Kepler, in his scientific works, made use of a special three-step proof (called a regressus) which had been originally proposed by the Lutheran theologian Philip Melanchthon, when identifying the cause of planetary motion, and also when attempting to derive a theory of light. A few highlights:

Kepler sought to find logically the “true cause” behind the virtus motrix (motive power) that moved the planets and determined their organization. (p. 44)

Kepler imposed fundamentally Lutheran principles onto the Neoplatonic concept of emanation, which he used as a guide in his physical investigation of the mechanical motive force of the solar system. (p. 52)

These conclusions allowed Kepler to theologically, mystically, and empirically confirm the motion of the planets as the effects of a universal, physical law. (p. 44)

Kepler claimed that the arrangement of the cosmos could have been proven logically using the idea of creation and appealing to the “divine blueprint” of a priori reasoning. (p. 47)

Now, if you believed that science cannot go outside the bounds of the natural world, as methodological naturalists do, then you certainly wouldn’t engage in a priori reasoning about a “divine blueprint” for the cosmos, while writing a scientific treatise. Obviously Kepler didn’t subscribe to methodological naturalism, as most modern scientists do. But if he didn’t, then why should we? And now ask yourself: would you allow Kepler’s scientific works into a high school science classroom? Or would you censor Kepler too?

(6) William Harvey (1578-1657), the founder of modern medicine.

Who was he and what was he famous for?

William Harvey founded modern physiology and embryology. He is famous for elucidating the complex nature of the heart’s functions and discovering the circulation of the blood.

How did he violate the principle of methodological naturalism?

In his scientific writings, he claimed that because things are “contrived and ordered with … most admirable and incomprehensible skill,” they point to “God, the Supreme and Omnipotent Creator.” Harvey also used Intelligent Design reasoning when making his most important scientific discovery: the circulation of the blood. Finally, he was a Christian who believed that the existence of purpose in nature reflected God’s design and intentions.

Where’s the evidence?

(a) Harvey put forward an Intelligent Design argument for a supernatural Creator in his scientific writings

In his book, Anatomical Exercises on the Generation of Animals (1651), William Harvey wrote:

“We acknowledge God, the Supreme and Omnipotent Creator, to be present in the production of all animals, and to point, as it were, with a finger to His existence in His works. All things are indeed contrived and ordered with singular providence, divine wisdom, and most admirable and incomprehensible skill. And to none can these attributes be referred save to the Almighty.”

(Harvey, William. 1989. Anatomical Exercises on the Generation of Animals. Toronto: Great Books of the Western World, William Benton, Publisher, Vol. 28, p. 443).

Harvey here states that all things, and especially animals, are “contrived and ordered with singular providence, divine wisdom, and most admirable and incomprehensible skill.” That’s theological talk. Harvey goes further, explicitly ascribing the design to God the Creator: “And to none can these attributes be referred save to the Almighty.” Hence Harvey is willing to “acknowledge God, the Supreme and Omnipotent Creator to be present in the production of all animals.” And remember, Harvey is writing all this in a scientific treatise, entitled: Anatomical Exercises on the Generation of Animals!

Does that sound like methodological naturalism to you? It looks like someone forgot to tell Harvey about the “rule” that science and the supernatural belong in separate compartments!

Notice also that Harvey is making, in broad outline, an Intelligent Design argument here. He is saying that because things are “contrived and ordered with … most admirable and incomprehensible skill,” they point to “God, the Supreme and Omnipotent Creator,” and to no-one else. In other words, Harvey believed that only a supernatural Creator could have designed the bodies of animals! That’s the polar opposite of methodological naturalism.

I should like to note in passing that the modern Intelligent Design movement is much more cautious in its claims: it simply asserts that biological complexity points to an Intelligent Designer, who may or may not be supernatural.

(b) The principles of Intelligent Design informed Harvey’s approach to science, when making his discovery of the circulation of the blood

It gets worse. Harvey used Intelligent Design reasoning when making his most important scientific discovery: the circulation of the blood. How do we know this? We have it on the testimony of the chemist Robert Boyle, who was a contemporary of Harvey’s. Dr. David Coppedge, who is a network engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, takes up the story in his online work, THE WORLD’S GREATEST CREATION SCIENTISTS From Y1K to Y2K:

In a recollection by Robert Boyle, Harvey, shortly before he died, related to the young chemist the clue to his discovery. Writing 31 years after Harvey’s death, Boyle recalls how he had asked the eminent physician about the things that induced him to consider the circulation of the blood:

He answer’d me, that when he took notice that the Valves in the Veins of so many several Parts of the Body, were so Plac’d that they gave free passage to the Blood Towards the Heart, but oppos’d the passage of the Venal Blood the Contrary way: He was invited to imagine, that so Provident a Cause as Nature had not so Plac’d so many Valves without design; and no Design seem’d more probable than that, since the Blood could not well, because of the interposing Valves, be sent by the Veins to the Limbs; it should be sent through the Arteries, and Return through the Veins, whose Valves did not oppose its course that way. (Emphasis added in all quotes.)

Lest this design by “Nature” appear Deistic, Emerson Thomas McMullen in Christian History (Issue 76, XXI:4, p. 41) stated that Harvey frequently “praised the workings of God’s sovereignty in creation — which he termed ‘Nature.'” We must not, in other words, read back 18th-century French concepts into 17th-century English terminology. McMullen, a PhD in the history and philosophy of science and a specialist in the life of Harvey, provides quotes that show Harvey’s provident Nature was an active, intelligent, wise, personal agent: Nature destines, ordains, intends, gives gifts, provides, counter-balances, institutes, is careful. Harvey spoke of the “skillful and careful craftsmanship of the valves and fibres and the rest of the fabric of the heart.” According to McMullen, Harvey’s primary achievement, the explanation of the circulation of the blood, was occasioned in part “by asking why God put so many valves in the veins and none in the arteries.” He believed that nature does nothing “in vain” (in Vein, perhaps, but not in Vain).

In the same article (No Vein Enquiry, in Christian History, Issue 76, XXI:4, p. 41), biographer Emerson Thomas McMullen explains that Harvey understood the Aristotelian principle, “Nature does nothing in vain,” in a theological sense:

Throughout his written works, Harvey reinterpreted the classical principle “Nature does nothing in vain” as a statement of God’s sovereign purposefulness in creating and sustaining the natural world (reflected in Isaiah 45:18).

(c) Harvey saw Creation as a reflection of God

We have seen how Harvey used theological reasoning in order to make scientific discoveries about Nature. But Harvey also believed that Nature could tell us about God, because for Harvey, the wonders of Nature were a reflection of their Creator. As he put it:

“The examination of the bodies of animals has always been my delight, and I have thought that we might thence not only obtain an insight into the lighter mysteries of nature, but there perceive a kind of image or reflection of the omnipotent Creator Himself.”

(Harvey, as cited in Keynes, Geoffrey. 1966. The Life of William Harvey. Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 330. Bold emphases mine – VJT.)

The foregoing quote from Harvey can also be found in an online article, No Vein Enquiry, by his biographer, Emerson Thomas McMullen, in Christian History (Issue 76, XXI:4, p. 41). Commenting on this quote, Dr. David Coppedge remarks in his online work, THE WORLD’S GREATEST CREATION SCIENTISTS From Y1K to Y2K:

This glimpse into Harvey’s leitmotiv shows him to be acting freely in a worshipful spirit as he undertook his scientific studies, not under compulsion as a naturalist trapped in a predominantly Christian culture. [Biographer Emerson Thomas] McMullen says that William Harvey was a “lifelong thinker on purpose” in anatomy and physiology, mentioning this throughout his writings in an effort to discern the final causes of things. This was not mere Aristotelianism. “Harvey was a Christian,” McMullen states unequivocally, “who believed that purpose in nature reflected God’s design and intentions.” The appeal of being able to glimpse something of the mind of God, to understand how he had made things work, in the hope of understanding more fully both God and his works, has been a frequent and productive force in the development of modern science.

I put it to my readers that Harvey’s whole approach to science was at odds with the tenets of methodological naturalism, which eschews any scientific appeal from the creature to the Creator, or vice versa.

(7) Bishop John Wilkins (1614–1672), Fellow of the Royal Society and one of its Twelve Founding Members

Who was he and what was he famous for?

John Wilkins FRS was an English clergyman, natural philosopher and author, as well as a founder of the Invisible College and one of the founders of The Royal Society. Wilkins was educated at Magdalen Hall (which later became Hertford College), Oxford, graduating with a B.A. in 1631 and an M.A. in 1634. He studied astronomy under John Bainbridge. He was ordained in the Church of England in 1637, and was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

John Wilkins is particularly known for his work, An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language, in which he proposed a universal language and a decimal system of weights and measures, not unlike our modern metric system.

How did he violate the principle of methodological naturalism?

Wilkins was also one of the leading founders of the new natural theology, which was highly compatible with the best science of his day. He also put forward an Intelligent Design argument for a supernatural Creator of the natural world.

Where’s the evidence?

(a) Bishop Wilkins put forward an Intelligent Design argument, based on the laws governing the movements of the heavenly bodies

In his work, Of the Principle and Duties of Natural Religion, London: 1675, he sets forth what can only be described as an Intelligent Design argument for a supernatural Creator of the cosmos:

Chapter VI Argument from the Admirable Contrivance of Natural Things

From that excellent contrivance which there is in all natural things. Both with respect to that elegance and beauty which they have in themselves separately considered, and that regular order and subserviency wherein they stand towards one another; together with the exact fitness and propriety, for the several purposes for which they are designed. From all which it may be inferred, that these are the productions of some Wise Agent.

The most sagacious man is not able to find out any blot or error in this volume of the world, as if any thing in it had been an imperfect essay at the first, which afterwards stood in need of mending: but all things continue as they were from the beginning of the creation.Tully [= Cicero – VJT] doth frequently insist on this, as that most natural result from that beauty to be observed in the universe. Esse praestantem aliquam, aeternamq; naturam & eam suspiciendam adoramq; hominem generi, pulchritudo ordoq; rerum celestium cogit confiteri. “The great order and elegance of things in the world, is abundant enough to evince the necessity of some eternal and absolute Being, to whom we owe adoration.” And in another place, quid potest esse tam apertam, tamque perspicuum, cum caelum suspeximus, caelestiaq; contemplati sumus, quam aliquod; esse Numen praestantissime mentis, quo haec regantur. “What can be more obvious, than to infer a supreme Deity, from that order and government we may behold amongst the heavenly bodies?”

The several vicissitues of night and day, winter and summer, the production of minerals, the growth of plants, the generation of animals, according to their several species, with the law of natural instinct, whereby everything is inclined and enabled, for its own preservation: The gathering of the inhabitants of the earth into nations, under distinct policies and governments, those advantages which each of them have of mutual commerce, for supplying the wants of the other, are so many arguments to the same purpose.

(b) Bishop Wilkins put forward an Intelligent Design argument, based on the laws governing the movements of the heavenly bodies

But Bishop Wilkins didn’t stop there. He immediately went on to say that the excellent contrivance of parts within the bodies of tiny animals (such as insects) proved beyond all doubt that God exists.

I cannot here omit the observations which have been made in these latter times, since we have had the use and improvement of the microscope, concerning that great difference which by the help of that, doth apppear betwixt natural and artificial things. Whatever is natural doth by that appear adorned in all elegance and beauty. There are such inimitable gildings and embroideries in the smallest seeds of plants, but especially in the parts of animals, in the head or eye of a small fly: such accurate order and symmetry in the frame of the most minute creatures, a louse or a mite, as no man were able to conceive without seeing of them. Whereas the most curious works of Art, the sharpest finest needle, doth appear as a blunt rough bar of iron coming from the furnace or the forge. The most accurate engravings or embossments seem such rude bungling deformed works, as if they had been done with a mattock or a trowel. So vast a difference is there between the skill of Nature and the rudeness or imperfection of Art.

And for such kind of bodies, as we are able to judge by our naked eyes, that excellent contrivance which there is in the several parts of them; their being so commodiously adapted to their proper uses, may be another argument to this purpose. As particularly those in human bodies, the consideration of which Galen himself, no great friend to religion, could not but acknowledge a Deity. In his book de Formatione Foetus, he takes notice, that there are in a human body above 600 several [= various – VJT] muscles, and there are at least 10 several intentions, or due qualifications, to be observed in each of these; proper figure, just magnitude, right disposition of its several ends, upper and lower position of the whole, the insertion of its proper nerves, veins and arteries, which are each of them to be duly placed, so that about the muscles alone, no less than 6,000 several ends or aims are to be attended to. The bones are reckoned to be 284; the distinct scopes or intentions of these, above forty; in all, about 100,000. And thus it is in some proportion all the other parts, the skin, ligaments, vessels, glandules, humours, but more especially with the several members of the body, which do in regard to the great variety and multitude of those several intentions which are required to them, very much exceed the homogeneous parts. And the failing in any one of these, would cause an irregularity of the body, and in many, such as would be very notorious.

And thus likewise is it in proportion with all other kinds of beings; minerals, vegetables: but especially such as are sensitive, insects, fishes, birds, Beasts; and in these yet more especially, for those organs and faculties that concern sensation: but most of all, for that kind of frame which relates to our understanding power, whereby we are able to correct the errors of our senses and imaginations, to call before us things past and future, and to behold things that are invisible to sense.

Now to imagine that all these things, according to their several kinds, could be brought into this regular frame and order, to which such an infinite number of intentions are required, without the contrivance of some Wise Agent, must needs be irrational in the highest degree.

(c) Bishop Wilkins argued that the general tendency of human psychological faculties to seek out what is good, points to a benevolent Creator

Wilkins went on to argue that human beings’ psychological faculties were oriented towards their well-being as individuals – a fact that could not be satisfactorily explained if they were the product of chance or necessity:

And then, as for the frame of human nature itself. If a man doth but consider how he is endowed with such a natural principle, whereby he is necessarily inclined to seek his own well-being and happiness: and likewise with one faculty whereby he is enabled to judge of the nature of things, as to their fitness or unfitness for this end: and another faculty whereby he is enabled to choose and promote such things as may promote his end, and to reject and avoid such things as may hinder it. And that nothing properly is his duty, but wht is really his interest: this may be another argument to convince him, that the author of his being must be infinitely wise and powerful.

The wisest man is not able to imagine how things should be better than now they are, supposing them to be contrived by the Wisest Agent; and where we meet with all the indications and evidences of such things as the Thing is capable of, supposing it to be true, it must needs be very irrational to make any doubt of it.

Now I appeal to any considering man, unto what Cause all this exactness and regularity can reasonably be ascribed, whether to blind Chance, or blind Necessity, or to the conduct of some wise intelligent Being.

Wilkins’ argument can be elucidated with the aid of a thought experiment. Imagine a race of beings who were physically like us in every respect, but whose psychological tendencies were totally unlike ours. For example, at breakfast time, they crave harmful drugs instead of cereal and fruit juice. If this race of beings were to follow their wishes, they would soon die. They could only continue as a race by continually fighting against their natural desires. Wilkins is saying that we are in no such unfortunate position. Our desires are actually conducive to our well-being. How lucky for us.

One might attempt to counter Wilkins’ argument by saying that a race of beings whose desires were conducive to their biological well-being would rapidly out-compete a race of psychologically twisted beings like the ones I have described in any Darwinian struggle for survival, and that the fact that animals generally tend to crave what is good for them is no mystery. Wilkins’ reply, if I read him aright, is that our general psychological tendencies as human beings – as distinguished from the perverted cravings of some depraved individual – are invariably oriented towards our own good, both as individuals and as social beings. Chance, he thinks, would not bring about such an optimal orientation.

From a modern perspective, Wilkins’ rosy view of human nature appears positively Pollyannaish. Nevertheless, it is a remarkable fact that individual and social interests almost invariably coincide, and that most individuals, most of the time, want what is good for them. Evolutionary theory is so far from explaining this fact that it cannot even account for why we want anything at all – in other words, it fails to account for the existence of consciousness. Leaving this point aside, however, there is another, more fundamental point that Wlikins makes in his argument: neither Chance nor Necessity can systematically produce good results.

(d) Bishop Wilkins argued that neither Chance nor Necessity can systematically produce good results

Wilkins finally delivers his coup de grace against atheistic accounts of the world: if the world is not governed by Wisdom, it must be governed by chance or necessity. Neither of these is systematically able to deliver good results. Yet in the world around us, creatures of various kinds do attain their good on a systematic basis. Consequently, the world must be governed by a wise Creator.

Though we should suppose both matter and motion to be eternal, it is not in the least credible, that insensible matter could be the author of all those excellent contrivances which we behold in these natural things. If anyone shall surmise, that these effects should proceed from the Anima Mundi [pantheistic World Soul – VJT], I should ask such a one, is this Anima Mundi an Intelligent Being, or is it void of all sense and perception? If it have no kind of sense or knowledge, then it is altogether needless to assert any such Principle, because matter and motion may serve for this purpose equally welll. If it be an Intelligent Wise, Eternal Being, this is GOD under another name.

As for Fate or Necessity, this must be as blind and unable to produce wise effects, as Chance itself.

From which it will follow, that it must be a Wise Being that is responsible for these wise effects.

By what hath been said upon this subject, it may appear, that these visible things of the world are sufficient to leave a man without excuse, as being the witnesses of a Deity, and such as do plainly declare his great Power and Glory.

Source: http://books.google.co.jp/books?id=oOpXqTPfxNsC&pg=PA55&hl=ja&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=4#v=onepage&q&f=false

Recommended reading

John Wilkins 1614-1672 by Barbara Shapiro.

Scientific Theology: Nature by Alister McGrath.

(8) Robert Boyle (1627-1691), Founding Member of The Royal Society and the founder of modern chemistry, best known for Boyle’s law.

Who was he and what was he famous for?

The seventeenth century chemist Robert Boyle was a Founding Member of the Royal Society. He was also the founder of modern chemistry. Today, he is best known for Boyle’s law (P.V = k).

How did he violate the principle of methodological naturalism?

Robert Boyle asserted that scientific discoveries revealing the astonishing complexity of living things, particularly tiny organisms such as insects, could be used to prove the existence of God.

Where’s the evidence?

(a) Boyle put forward Intelligent Design arguments in his works

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Boyle fastens on two main types of design arguments: those involving the complexity of animate beings, particularly very small animate beings, and those which highlight the need to explain the origin and continuing function of natural laws: God must not only sustain God’s creatures, Boyle argues, he must also sustain the regularities which we recognize as lawlike.

(MacIntosh, J. J. and Anstey, Peter, Robert Boyle, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2010 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2010/entries/boyle/#2.)

Boyle genuinely admired the exquisite workmanship involved in the way God made insects, and he saw these creatures as providing a cogent proof of God’s existence:

“God, in these little Creatures, oftentimes draws traces of Omniscience, too delicate to be liable to be ascrib’d to any other Cause… my wonder dwells not so much on Nature’s Clocks (is I may so speak) as on her Watches.”

(The Works of Robert Boyle, Hunter, M., and Davis, E. B. (eds.), 14 vols., London: Pickering and Chatto, 1999–2000. Citation is from vol. 3, p. 223. See also Birch, T., 1772, The Works of the Honourable Robert Boyle, Thomas Birch, (ed.), 6 vols. (London, 1772; reprinted Hildesheim: George Olms, 1966), a reprinting of the five volume 1744 edition. Citation is from vol. 2, p. 22.)

Clocks, watches, complexity of little creatures … does that sound familiar to my readers? Robert Boyle, the scientist, is making an Intelligent Design argument! He didn’t feel in the least embarrassed about putting forward such an argument, as he undoubtedly would have done, had there been a widely observed convention in the 17th century that scientific reasoning should not be used to argue for the existence of God. Evidently there was no such convention. Which prompts me to ask: if 17th century scientists felt free to put forward Intelligent Design style arguments, then on what basis do modern scientists assert that these arguments fall outside the boundaries of science? Who decides what “real science” is?

(b) Boyle argued on empirical grounds for the reality of miracles

Finally, Boyle firmly believed in the reality of miracles. He was extremely skeptical of miracles outside the Bible, but he was also worried about the possibility of deceptive, demonic miracles. He wrote:

I first assent to a Natural Religion upon the score of Natural Reason antecedently to any particular Revelation. And then; if a Miracle be wrought to attest to a particular doctine concerning Religion, I endeavor according to the principles of Natural Religion and right Reason, to discover or not, this proposd Doctrine be such, that I ought to looke upon a Miracle that is vouch’d for it, as comeing from God or not. And lastly if I find, by the Agreeableness of it to the best notions that natural Theology gives us of God and His Attributes, that His Religion cannot in reason be doubted to come from Him; I then judge the body of the Religion to be true.

(BP 7: 122-3). Quoted in Boyle on atheism by Robert Boyle, transcribed and edited by John James Macintosh, University of Toronto Press, 2006, p. 206.)

Boyle went on to acknowledge that there may be “Lying Miracles” which God permits “to try men.”

(c) Boyle on mechanical and final causes in Nature

Boyle is believed by some to have been opposed to Aristotle’s appeal to final causes in Nature. In fact, his real position was considerably more nuanced. Boyle was no ant-teleologist. In his work, A Disquisition About the Final Causes of Natural Things, Boyle argued that the appeal to final causes in science is valid, but that they must be used with caution:

The result of what has been hitherto discoursed, upon the four questions proposed at the beginning of this small treatise, amounts in short to this:

- That all consideration of final causes is not to be banished from natural philosophy; but that it is rather allowable, and in some cases commendable, to observe and argue from the manifest uses of things, that the author of nature pre-ordained those ends and uses.

- That the sun, moon and other celestial bodies, excellently declare the power and wisdom, and consequently the glory of God; and were some of them, among other purposes, made to be serviceable to man.

- That from the supposed ends of inanimate bodies, whether celestial or sublunary, it is very unsafe to draw arguments to prove the particular nature of those bodies, or the true system of the universe.

- That as to animals, and the more perfect sorts of vegetables, it is warrantable, not presumptuous, to say, that such and such parts were pre-ordained to such and such uses, relating to the welfare of the animal (or plant) itself, or to the species it belongs to: but that such arguments may easily deceive, if those, that frame them, are not very cautious, and careful to avoid mistaking, among the various ends, that nature may have in the contrivance of an animal’s body, and the various ways, which she may successfully take to compass the same ends. And,

- That, however, a naturalist, who would deserve that name, must not let the search or knowledge of final causes make him neglect the industrious indagation of efficients.

[Works, V, 444]

In his work, Boyle on atheism, Professor Macintosh notes:

For Boyle there was the realm of things to be explained scientifically, … but there were also many things that required supernatural intervention, including God’s sustaining His creatures in existence, sustaining the system as a lawlike entity or automaton, granting incorproeal souls to corporeal humans (‘physical miracles’ which occur hundreds of times each day), and ensuring that there was a lawlike connection between the sensory input of animals and the intellectual abstractions they were able to perform. Also in need of explanation was the mechanically inexplicable ability of people – that is, incorporeal souls – to move matter. Additionally, people seemed to be able to acquire knowledge beyond their ordinary ken, providing a prima facie case for angelic intervention. There were apparent miracles of healing and apparent cases of diabolical communication. There were cases of things that could in some sense be explained naturally but that seemed to Boyle to be much happier wearing supernatural explanations than natural ones, the most interesting being the spreas and survival of the Christian religion – a ‘permanent’ as opposed to other, ‘transient,’ miracles. There were cases of created intellects apparently being able to foretell the future. And then there were cases of supernatural with an apparent intention to validate a particular instituted religion or one in the process of becoming instituted.

For Boyle the world is split up into events which have a mechanical explanation and those which do not. The ones that have a mechanical explanation are thereby lawlike. Of the ones which do not, some are lawlike in their regularity and some are not, but it is clear that supernatural intervention in Boyle’s system is pretty much a commonplace. (Boyle on atheism by Robert Boyle, transcribed and edited by John James Macintosh, University of Toronto Press, 2006, pp. 207-208.)

Supernatural explanation is “pretty much a commonplace”? That certainly doesn’t sound like a methodological naturalist to me!

(9) John Ray, (1627-1705), founder of Modern Biology and Natural History, and the first to put forward a rigorous definition of a species.

Who was he and what was he famous for?

John Ray founded the science of modern biology, just as Robert Boyle founded modern chemistry. In his book, The Founders of British Science: John Wilkins, Robert Boyle, John Ray, Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, Isaac Newton (Cresset Press, London, 1960, p. 94), J.G. Crowther describes the relationship between the work of these two scientists as follows:

‘The work of recording and classifying the contents of nature, which, as Bacon had indicated, was the first step in creating a modern universal science, was led in chemistry by Boyle. In biology the comparable work was carried out by John Ray.

How did he violate the principle of methodological naturalism?

In the course of his scientific research, John Ray found abundant evidence that all things – not only the heavens and the earth, but also living organisms – had been created by an infinitely wise and loving God. He maintained that the exquisite detail of the structure and function of living organisms was clear evidence of God’s wisdom.

Where’s the evidence?

(a) Ray argued that the scientific refutation of the doctrine of spontaneous generation discredited atheism

Ray mounted a powerful cumulative case for a Creator of Nature in a book entitled The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation (1691), which became a best-selling classic. In his book, Ray argued forcefully against the doctrine of spontaneous generation (the notion that life can arise from non-living matter), which he contemptuously described as “the Atheist’s fictitious and ridiculous Account of the first production of Mankind, and other Animals“:

Another Observation I shall add concerning Generation, which is of some moment, because it takes away some Concessions of Naturalists that give countenance to the Atheist’s fictitious and ridiculous Account of the first production of Mankind, and other Animals, viz. that all sorts of Insects, yea, and some Quadrupeds too, as Frogs and Mice, arc produced spontaneously. My Observation and Affirmation is, that there is no such thing in Nature, as AEquivocal or Spontaneous Generation, but that all Animals, as well small as great, not excluding the vilest and most contemptible insect, are generated by Animal Parents of the same Species with themselves; that Noble Italian Vertuoso, Francisco Redi, having experimented, that no putrified Flesh (which one would think were the most likely of any thing) will of itself, if all Insects be carefully kept from it, produce any: The same Experiment, I remember, Dr. Wilkins, late Bishop of Chester, told me, had been made by some of the Royal Society. No Instance against this Opinion doth so much puzzle me, as Worms bred in the Intestines of Man, and other Animals. But Seeing the round Worms do manifestly generate, and probably the other Kinds too, it’s likely they come originally from Seed, which how it was brought into the Guts, may afterwards possibly be discovered.

Moreover, I am inclinable to believe, that all Plants too, that themselves produce Seed, which are all but some very imperfect ones, which scarce deserve the Name of Plants) come of Seeds themselves. For that great Naturalist Malpighius, to make Experiment whether Earth would of itself put forth Plants, took some purposely digged out of a deep place, and put it into a Glass-Vessel, the Top whereof he covered with Silk many times doubled, and strained over it, which would admit the Water and Air to pass through, but exclude the least Seed that might be wafted by the Wind; the Event was that no Plant at all sprang up in it… (The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation, Part II, pp. 298-299, available online here ).

(b) Ray was a proponent of Intelligent Design

Ray also put forward an Intelligent Design argument in his book, when he reasoned that the absence of any maladaptive parts in the human body attests to the existence of an infinitely wise and benevolent God as our Creator:

Had we been born with a large Wen upon our Faces, or a Bavarian Poke under our Chins, or a great Bunch upon our Backs like Camels, or any the like superfluous Excrescency; which should be not only useless but troublesome, not only Stand us in no stead, but also be ill-favoured to behold, and burdensome to carry about, then we might have had some Pretence to doubt whether an intelligent and bountiful Creator had been our Architect; for had the Body been made by Chance, it must in all likelihood have had many of these superfluous and unnecessary Parts.

But now seeing there is none of our Members but hath its Place and Use, none that we could spare, or conveniently live without were it but those we account Excrements, the Hair of our Heads, or the Nails on our Fingers ends; we must needs be mad or sottish if we can conceive any other than that an infinitely Good and Wise God was our Author and Former…

(The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation, Part II, pp. 228-229, available online here).

Modern biologists would vigorously contest Ray’s assertion that none of our body parts are maladaptive, but regardless of whether you agree with Ray or not, the point is that he intended his argument for the existence of an Infinite God as a scientific one. He knew nothing of any “bright-line” rule saying that science cannot furnish arguments for the supernatural.

The modern Intelligent Design movement is much more modest than John Ray in its claims: it does not state that only God could have produced the first living things, but that only an Intelligent Agent could have done so. One cannot therefore accuse the Intelligent Design movement of bringing religion into the classroom.

(10) Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), the father of microscopy.

Who was he and what was he famous for?