|

|

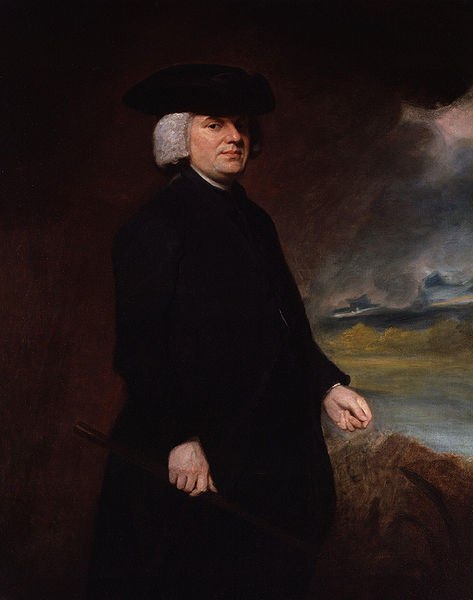

There are many modern-day skeptics who apparently still subscribe to the myth that the Scottish empiricist philosopher David Hume soundly refuted Rev. William Paley’s argument from design on philosophical grounds, even before Darwin supposedly refuted it on scientific grounds (see here, here and here for examples). The supposition is absurdly anachronistic: Hume died in 1776, and his posthumous Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion were published in 1779, but Paley’s Natural Theology was not published until 1802, three years before Paley’s death in 1805. Some of the more intelligent skeptics, such as Julian Baggini, are aware of this fact, but still make the risibly absurd claim (see here) that Hume anticipated and refuted Paley’s argument from design. The truth, however, is the complete reverse.

It turns out that Rev. Paley had already read Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion; indeed, he even refers in passing to “Mr. Hume, in his posthumous dialogues” on page 512 of Chapter XXVI of his Natural Theology! Moreover, a careful examination of Paley’s design argument shows that he had anticipated and responded to all of Hume’s criticisms.

I’d like to begin by drawing attention to one major difference between the design argument put forward by the character Cleanthes (and subsequently refuted by Philo) in David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, and the design argument formulated by William Paley. As Professor John Wright has pointed out in some online remarks on Hume’s Dialogues, Cleanthes’ design argument was an inductive argument based on an analogy between human artifacts (which we observe being produced by intelligent agents) and the machines we find in Nature, whereas Paley argued that we could immediately infer Intelligent Design from any machine we happen to find:

Paley thinks we infer the existence of an intelligent cause immediately from the observation of the machine itself. According to the argument which Cleanthes puts forward, the only reason we ascribe an intelligent cause to machines like watches, is because we discover from observation that they are created by beings with thought, wisdom and intelligence. (Paley had read Hume and was obviously aware of this difference in their arguments: see his answer to his first Objection.)

For Paley the inference from watch to intelligent watchmaker is no different from the inference from complex natural organisms to an intelligent designer. He is just trying to show you can make the same inference in both cases. For Cleanthes, on the other hand, it is important that we observe the maker in the case of the human productions and we do not in the case of the productions of nature. We observe the effects in both cases and that they are somewhat similar to each other. But we never observe the cause in the case of natural machines: it is only inferred through the scientific principle “like effects, like causes.” Cleanthes draws the conclusion that the cause of natural machines something like a human mind, but very much greater.

Cleanthes’ argument is a genuine inductive argument, based on observation of the relation of cause and effect in the case of human production; Paley’s is not.

I should add that Dr. Stephen Meyer, author of Signature in the Cell, made the same point in an online lecture he gave at Cambridge University in July 2012, entitled, Intelligent Design: The Most Credible Idea?. At about (52:30), Meyer addresses Hume’s objections to the design argument, as follows:

The other case against the design argument came from Hume, which was the claim that the design argument was a failed analogy. And what he did was, he said, “Look. You’ve got the structure of the analogical argument is that you’ve got two similar effects with a known cause, allowing us to infer a similar cause for the other effect.” That’s the logical structure of the analogical argument. Hume attempted to defeat that by showing that the similarity between effect E1 – human artifacts – and effect E2 – living systems – was much less than had been previously indicated. The structure of the argument that I’ve developed – and that other people in the ID research community are developing – is not an analogical argument, properly speaking. We’re not arguing from similarities of effects; rather, what we’re doing is picking out identical effects in both living systems and artifactual systems – in particular, specified complexity, which can be very rigorously defined – and saying, “OK, we’re looking at identical effects. Now what is the best causal explanation of that effect given our knowledge of cause and effect? So the argument does not have the logical structure of an analogical argument of the kind that Hume critiqued, but rather, of an inference to the best explanation – a standard scientific form of argumentation – and so the case I made is that Cause 4 – Intelligence – provides a better explanation, because it’s the only cause which is consistent with our knowledge of cause and effect as we observe it in the world around us, as we observe the causes now in operation.

Dr. Meyer is of course perfectly correct. In this post, what I propose to do is examine Hume’s criticisms of the design argument in detail, and show how Paley’s version of the design argument was specifically tailored to address those criticisms head-on.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Twelve myths about Paley’s design argument, or: Why everything you thought you knew about Paley’s Natural Theology is wrong

If you’ve read anything about Paley’s “design argument” for the existence of God, then you’ve probably heard it expressed in the following garbled form:

Rev. William Paley argued that there were strong similarities between complex structures that we find in Nature (such as the eye) and human artifacts, such as a watch. The human eye is like a machine, he claimed. So are the other organs of the body. But we already know from observation that mechanical artifacts, such as watches, are invariably designed by intelligent beings – namely, human beings. Operating on the principle, “like effects, like causes,” we can infer by analogy that complex organs, such as the eye, were probably made by an Intelligent Designer, Who is like a human being, but much, much smarter. Since this inference is based on an inductive argument (rather than a deductive one) which makes use of an analogy, its conclusion is not absolutely certain. Nevertheless, maintained Paley, it is extremely probable that an Intelligent Designer exists. Paley then went on to argue that since the whole world is rather like a giant watch, we may legitimately conclude that the universe was made by a Designer – a Cosmic Watchmaker, if you like.

You’ve probably also read about Hume’s allegedly devastating rebuttal of the Design argument, which basically goes like this:

First, Paley’s “watch analogy” for complex natural systems was never a very good one in the first place. The eye isn’t a watch, and neither is the universe. The numerous disanalogies between complex natural structures (such as the eye) and a human artifact, undermine the inference that these natural structures were designed. The design inference is even weaker when we examine the universe as a whole: in reality, it is nothing like a watch.

Second, the numerous defects that we find in the organs of living things constitute powerful evidence against the hypothesis that they were designed by an Intelligent Creator.

Third, even if we had good evidence for an Intelligent Designer of Nature, our experience tells us that intelligent designers are invariably complex entities, so we would then have to ask: who designed the Designer? And who designed the Designer’s Designer? And so on, ad infinitum. Wouldn’t it be more rational, then, to simply say that Nature is self-ordering, instead of opening the door to an infinite regress of designers, which in the end, explains nothing?

Fourth, even if we could establish the existence of a Designer of Nature who can somehow avoid this infinite regress, we would still faced with another question: how can the Designer of Nature be a bodiless agent, as theists maintain? Our experience tells us that intelligent agents are always embodied beings, and nobody has ever seen a disembodied agent making anything. There is no good evidence for spooks. The notion of a spiritual Designer is therefore both absurd and unsupported by any credible evidence.

Fifth, even if could make sense of the notion of a spiritual Designer, how can we be sure that there’s only one Designer of Nature? Might there not be many designers, as polytheism supposes?

Sixth, even if we could establish the unity of the Cosmic Watchmaker, such a Being would not need to be continually involved with the cosmos; maybe He created its complex systems at some point in the past, but He no longer interacts with the cosmos. So how do we know that the Designer of the cosmos is still alive?

Seventh, even if He still exists, we have no way of knowing whether the Cosmic Designer is a personal Being; for all we know, the Designer might be an impersonal force, like Spinoza’s Deity.

Finally, even if we could establish that the Designer is a personal Being, there is no way of demonstrating that He is infinitely powerful, wise or good. The effects we see in Nature are finite, and from a finite effect, it is illicit to infer the existence of an Infinite Cause.

We can only conclude, then, that Rev. William Paley’s identification of the Designer of Nature with the God of Judaism and Christianity in his Natural Theology is utterly unwarranted: it is a gigantic leap of faith which defies the laws of logic.

The above exposition of Paley’s design argument contains several errors, which I’ve collected together under the heading of twelve myths, which are commonly found in discussions of Paley’s argument for God’s existence. My refutation of these myths will enable readers to see clearly how Paley met and rebutted every one of the eight Humean criticisms listed above.

The biggest myth of them all: Paley failed to take biological reproduction into account, in his argument

Perhaps the biggest myth – especially among younger skeptics – is that Rev. Paley failed to take into account the rather obvious fact that organisms reproduce (and are therefore capable of refining and improving upon their internal bodily design with each generation), whereas artifacts typically don’t reproduce – which is why design inferences that work for watches don’t work for living things. At the end of my post, I’ll prove that Paley anticipated this very objection and rebutted it decisively, before going on to discuss briefly whether Darwin’s Origin of Species successfully refutes the logic of Paley’s argument.

Without further ado, allow me to present “Twelve myths about Paley’s design argument.”

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth One: Paley likens the world to a giant watch in his Natural Theology.

|

A Russian mechanical watch. Image courtesy of Kristoferb and Wikipedia.

Fact: Paley explicitly rejected the analogy between the world and a watch, in his Natural Theology. He points out that when making design inferences, “we deduce design from relation, aptitude, and correspondence of parts.” However, “the heavenly bodies do not, except perhaps in the instance of Saturn’s ring, present themselves to our observation as compounded of parts at all,” since they appear to be quite simple and undifferentiated in their internal structure (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXII, p. 379). When discussing the movements of the heavenly bodies, he writes: “Even those things which are made to imitate and represent them, such as orreries, planetaria, celestial globes, &c. bear no affinity to them, in the cause and principle by which their motions are actuated” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXII, p. 379) – the reason being that the mechanism of a watch requires that its parts be in physical contact with one another, whereas the gravitational influence exerted by one heavenly body on another is action at a distance.

Indeed, nowhere in his Natural Theology does Paley declare that the world is like a watch. The closest statement I can find is his declaration, “The universe itself is a system; each part either depending upon other parts, or being connected with other parts by some common law of motion, or by the presence of some common substance” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXV, pp. 449-450). To be sure, Paley does argue that “In the works of nature we trace mechanism” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, pp. 416-418), but he never declares that Nature itself is one giant mechanism. Rather, Paley’s proof of God was based on the existence of mechanisms (plural) occurring in the natural world.

What Paley does liken to watches are the biological structures (such as the eye) that we find in the natural world. For example, he writes that “very indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater and more, and that in a degree which exceeds all computation,” and in the same passage he adds that “here is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision, as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter III, pp. 17-18).

NOTE: I should like to point out here that when Paley speaks of contrivances, he simply means: systems whose parts are intricately arranged and co-ordinated to serve some common end, or as he puts it, a system possessing the following three features: “relation to an end, relation of parts to one another, and to a common purpose.” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 413.) For the purposes of Paley’s argument, it is utterly irrelevant whether this end is intrinsic to the parts in question, as in a living organism, or extrinsic, as in an artifact.

Elsewhere, when discussing the example of the eye and other organs, he writes: “If there were but one watch in the world, it would not be less certain that it had a maker… Of this point, each machine is a proof, independently of all the rest. So it is with the evidences of a Divine agency… The eye proves it without the ear; the ear without the eye.” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter VI, pages 76-77).

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Two: Paley’s argument for a Designer in his Natural Theology is an argument from analogy.

Fact: Paley’s argument is not based on any analogy. He doesn’t say that the complex organs found in living things are like artifacts; he says that they are the same as artifacts in certain vital respects. In particular, these complex organs share several common properties with artifacts: “properties, such as relation to an end, relation of parts to one another, and to a common purpose” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 413), or as he puts it elsewhere, “[a]rrangement, disposition of parts, subserviency of means to an end, [and] relation of instruments to a use” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter II, p. 11). Paley refers to the organs of the body as “contrivances,” precisely because they share these vital properties with man-made artifacts. (For the benefit of Thomist readers who may be wondering, I should point out that Paley is fully aware of the intrinsic teleology of living things, and that he repeatedly refers to “final causes” in his Natural Theology.)

Next, Paley argues that intelligence is the only known adequate cause of objects possessing the combination of properties found in artifacts and complex organs. Our experience tells us that that no other cause, apart from intelligence, is capable of producing effects possessing these properties. Paley concludes that the complex organs of living creatures (such as the eye) must therefore have had an Intelligent Designer. In his own words:

Wherever we see marks of contrivance, we are led for its cause to an intelligent author. And this transition of the understanding is founded upon uniform experience. We see intelligence constantly contriving, that is, we see intelligence constantly producing effects, marked and distinguished by certain properties; not certain particular properties, but by a kind and class of properties, such as relation to an end, relation of parts to one another, and to a common purpose. We see, wherever we are witnesses to the actual formation of things, nothing except intelligence producing effects so marked and distinguished. Furnished with this experience, we view the productions of nature. We observe them also marked and distinguished in the same manner. We wish to account for their origin. Our experience suggests a cause perfectly adequate to this account. No experience, no single instance or example, can be offered in favour of any other. In this cause therefore we ought to rest… Men are not deceived by this reasoning: for whenever it happens, as it sometimes does happen, that the truth comes to be known by direct information, it turns out to be what was expected. In like manner, and upon the same foundation (which in truth is that of experience), we conclude that the works of nature proceed from intelligence and design, because, in the properties of relation to a purpose, subserviency to a use, they resemble what intelligence and design are constantly producing, and what nothing except intelligence and design ever produce at all. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 413-414).

For Paley, the inference to design, upon seeing a contrivance, is immediate:

This mechanism being observed (it requires indeed an examination of the instrument, and perhaps some previous knowledge of the subject, to perceive and understand it; but being once, as we have said, observed and understood), the inference, we think, is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker…

Nor would it, I apprehend, weaken the conclusion, that we had never seen a watch made; that we had never known an artist capable of making one; that we were altogether incapable of executing such a piece of workmanship ourselves, or of understanding in what manner it was performed…

Ignorance of this kind exalts our opinion of the unseen and unknown artist’s skill, if he be unseen and unknown, but raises no doubt in our minds of the existence and agency of such an artist, at some former time, and in some place or other. (Chapter I, pp. 3-4)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Three: Paley put forward an inductive argument for a Designer: because there are complex systems in Nature which resemble human artifacts, which are made by intelligent agents, we can infer that an Intelligent Designer made Nature’s complex systems.

Sherlock Holmes, a fictional detective who was renowned for his powers of deductive logic, and his companion Dr. Watson. Holmes’ most famous remark was one he made to Dr. Watson in chapter 6 of The Sign of the Four: “How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?” Image courtesy of Wikipedia. Illustration by Sidney Paget from the Sherlock Holmes story The Greek Interpreter.

William Paley put forward what he claimed was a deductive proof of the existence of an Intelligent Designer of Nature. For example, in his Natural Theology, he refers to “the marks of contrivance discoverable in animal bodies, and to the argument deduced from them, in proof of design, and of a designing Creator.” (Natural Theology, 12th edition, J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter IV, p. 67.)

Fact: Paley himself declares on several occasions that his argument for a Designer of Nature is a deductive argument. Paley refers to his argument as a deductive argument in the following passages in his Natural Theology:

…the marks of contrivance discoverable in animal bodies, and to the argument deduced from them, in proof of design, and of a designing Creator…

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter IV, p. 67)

Now we deduce design from relation, aptitude, and correspondence of parts.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXII, p. 379)

… the universality which enters into the idea of God, as deduced from the views of nature.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 443)

Nowhere in his Natural Theology does Paley ever describe his argument as an inductive one.

The premises and conclusion of Paley’s deductive design argument

The premises of Paley’s deductive argument are as follows. First, we know that intelligent agents are capable of producing effects marked by the three properties of (i) relation to an end, (ii) relation of the parts to one another, and (iii) possession of a common purpose.

Second, no other cause has ever been observed to produce effects possessing these three properties.

We are therefore entitled to conclude that if there are systems in Nature possessing these same three properties, then the only cause that is adequate to account for these natural effects is an Intelligent Agent.

The view that Paley’s argument is deductive has scholarly support

I would like to add that Thomist scholar Del Ratzsch, in his article on Teleological Arguments for God’s Existence in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, also acknowledges that Paley’s argument is a deductive one. In his article, he writes:

Although Paley’s argument is routinely construed as analogical, it in fact contains an informal statement of the above variant argument type. Paley goes on for two chapters discussing the watch, discussing the properties in it which evince design, destroying potential objections to concluding design in the watch, and discussing what can and cannot be concluded about the watch’s designer. It is only then that entities in nature – e.g., the eye – come onto the horizon at all. Obviously, Paley isn’t making such heavy weather to persuade his readers to concede that the watch really is designed and has a designer. He is, in fact, teasing out the bases and procedures from and by which we should and should not reason about design and designers. Thus Paley’s use of the term “inference” in connection with the watch’s designer.

Once having acquired the relevant principles, then in Chapter 3 of Natural Theology – “Application of the Argument” – Paley applies the same argument (vs. presenting us with the other half of the analogical argument) to things in nature. The cases of human artifacts and nature represent two separate inference instances:

up to the limit, the reasoning is as clear and certain in the one case as in the other. (Paley 1802 [1963], 14)

But the instances are instances of the same inferential move:

there is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it. (Paley 1802 [1963], 13)

The watch does play an obvious and crucial role – but as a paradigmatic instance of design inferences rather than as the analogical foundation for an inferential comparison.

… Indeed, it has been argued that Paley was aware of Hume’s earlier attacks on analogical design arguments, and deliberately structured his argument to avoid the relevant pitfalls. Paley’s own characterization of his argument would support this deductive classification…

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Four: Paley’s argument for God in his Natural Theology is a merely probabilistic argument, rather than a demonstrative proof.

Left hip-joint, opened by removing the floor of the acetabulum from within the pelvis. Image courtesy of Gray’s Anatomy and Wikipedia.

For William Paley, the ligament of the ball-and-socket joint proved the existence of a Designer beyond all shadow of a doubt.

Fact: Paley explicitly states, over and over again, in his Natural Theology, that he views his argument for a Designer not as a merely probabilistic argument, but as a proof, whose conclusion was certain and indubitable. For example, in his discussion of the ligament of the ball-and-socket joint of the thigh (illustrated above), Paley declares that it provides us with unequivocal proof of a Creator:

If I had been permitted to frame a proof of contrivance, such as might satisfy the most distrustful inquirer, I know not whether I could have chosen an example of mechanism more unequivocal, or more free from objection, than this ligament. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter VIII, pp. 112-113).

Referring to the human eye, Paley wrote:

Were there no example in the world, of contrivance, except that of the eye, it would be alone sufficient to support the conclusion which we draw from it, as to the necessity of an intelligent Creator. It could never be got rid of; because it could not be accounted for by any other supposition, which did not contradict all the principles we possess of knowledge; the principles, according to which, things do, as often as they can be brought to the test of experience, turn out to be true or false.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter VI, p. 75)

After describing the circulation of the blood, he writes: “Can any one doubt of contrivance here; or is it possible to shut our eyes against the proof of it?” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter X, p. 161).

Finally, in summing up his case, Paley wrote:

For my part, I take my stand in human anatomy: and the examples of mechanism I should be apt to draw out from the copious catalogue, which it supplies, are the pivot upon which the head turns, the ligament within the socket of the hip-joint, the pulley or trochlear muscles of the eye, the epiglottis, the bandages which tie down the tendons of the wrist and instep, the slit or perforated muscles at the hands and feet, the knitting of the intestines to the mesentery, the course of the chyle into the blood, and the constitution of the sexes as extended throughout the whole of the animal creation. To these instances, the reader’s memory will go back, as they are severally set forth in their places; there is not one of the number which I do not think decisive; not one which is not strictly mechanical; nor have I read or heard of any solution of these appearances, which, in the smallest degree, shakes the conclusion that we build upon them.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, p. 536).

Paley’s clinching argument: if the design skeptics are right, then all design inferences are invalid, which is absurd

Paley puts forward one final argument to convince diehard skeptics in his day, who were still inclined doubt the legitimacy of any inference from the numerous contrivances that we find in the natural world to the existence of a Designer of Nature. He offers a reductio ad absurdum: if the skeptics are right, he says, an absurd consequence follows: it would mean that no matter how perfectly ordered the universe was, we could still never be sure that it had an Intelligent Creator. No sane person would accept such a ridiculous conclusion, he says:

Of every argument, which would raise a question as to the safety of this reasoning, it may be observed, that if such argument be listened to, it leads to the inference, not only that the present order of nature is insufficient to prove the existence of an intelligent Creator, but that no imaginable order would be sufficient to prove it; that no contrivance, were it ever so mechanical, ever so precise, ever so clear, ever so perfectly like those which we ourselves employ, would support this conclusion. A doctrine, to which, I conceive, no sound mind can assent.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, pp. 414-415)

Paley’s probable conclusions as to the functions of various bodily organs, contrasted with his certainty that they were designed

It is true that in Paley’s Natural Theology, the term “probable” is used when Paley is speculating as to the possible purposes of the various contrivances that we find in Nature – especially, the organs of the human body. Thus he considers it probable (but not certain) that the purpose of the blood circulation is to “distribute nourishment to the different parts of the body”. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter X, p. 164.)

At the same time, however, Paley is quite emphatic that our lack of certainty regarding the precise purpose for which the various contrivances occurring in organisms were designed does not weaken the certainty of the inference that they were designed. Thus Paley is absolutely certain that the valves which regulate the flow of blood were designed by an intelligent agent. “Can any one doubt of contrivance here?” he asks rhetorically. He even wonders how it is possible “to shut our eyes against the proof of it.” Thus in the same passage, Paley expresses his absolute certainty on the question of whether the valves of the blood vessels were designed, while acknowledging that he is uncertain as to what the blood circulation is designed for. The term “probably” is only used in connection with the latter question, not the former.

So long as the blood proceeds in its proper course, the membranes which compose the valve, are pressed close to the side of the vessel, and occasion no impediment to the circulation: when the blood would regurgitate, they are raised from the side of the vessel, and, meeting in the middle of its cavity, shut up the channel. Can any one doubt of contrivance here; or is it possible to shut our eyes against the proof of it?

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter X, p. 161)

|

A Red Pierrot butterfly, feeding at the M.E.S. Abasaheb Garware College campus in Pune, India. Image courtesy of Akshay Rao and Wikipedia.

Finally, Paley regarded the existence of beauty in the plant and animal kingdoms as a most remarkable fact, and he considered it probable, but not certain, that the beauty we observe in living creatures was the product of design. The reader may be wondering why Paley hesitated to draw the design inference here. Of the complexity of “parts and materials” there could be no doubt: Paley writes admiringly of “the painted wings of butterflies and beetles,” and “the rich colours and spotted lustre of many tribes of insects.” However, we need to recall that for Paley, a contrivance (which for Paley, necessarily requires a Designer) is more than a complex arrangement of parts. The parts have to serve a common end. Now, with the body’s internal organs, the end is usually (but not always) readily discernible, because it is a biological end. A biological function, once established, leaves no room for argument. However, the beauty of the external coloring of a plant or animal often does not appear to serve any biological function, leaving Paley somewhat perplexed. Perhaps, he suggests, animal beauty is meant to attract other animals. Perhaps the beauty of flowers serves the same purpose. Now that would qualify as a bona fide end, if it were confirmed. At the same time, Paley was troubled by the existence of complex systems of parts which seemed to serve no other purpose than ornamentation.

A third general property of animal forms is beauty. I do not mean relative beauty, or that of one individual above another of the same species, or of one species compared with another species; but I mean, generally, the provision which is made in the body of almost every animal, to adapt its appearance to the perception of the animals with which it converses. In our own species, for example, only consider what the parts and materials are, of which the fairest body is composed; and no further observation will be necessary to show, how well these things are wrapped up, so as to form a mass, which shall be capable of symmetry in its proportion, and of beauty in its aspect…

All which seems to be a strong indication of design, and of a design studiously directed to this purpose. And it being once allowed, that such a purpose existed with respect to any of the productions of nature, we may refer, with a considerable degree of probability, other particulars to the same intention; such as the teints of flowers, the plumage of birds, the furs of beasts, the bright scales of fishes, the painted wings of butterflies and beetles, the rich colours and spotted lustre of many tribes of insects.

In plants, especially in the flowers of plants, the principle of beauty holds a still more considerable place in their composition; is still more confessed than in animals. Why, for one instance out of a thousand, does the corolla of the tulip, when advanced to its size and maturity, change its colour? … It seems a lame account to call it, as it has been called, a disease of the plant. Is it not more probable, that this property, which is independent, as it should seem, of the wants and utilities of the plant, was calculated for beauty, intended for display?

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XI, pp. 197-199)

Here, then, Paley’s cautious assertion that the beauty observed in animals and plants gives “a strong indication of design” with “a considerable degree of probability” reflects his lack of certainty as to whether beauty actually serves a legitimate biological purpose in the organisms in which it is found.

The point that Paley is making here is that we need to be absolutely certain that there is a purpose served by a complex arrangement of parts, before we can impute design to it. Once we have ascertained that the parts do indeed serve a common purpose, the inference to an Intelligent Designer is absolutely certain.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Five: Paley overlooked the numerous disanalogies between complex natural structures (such as the eye) and a human artifact, such as a watch. Additionally, his watch analogy for the cosmos was a very poor one.

|

The human eye. According to William Paley, “Were there no example in the world, of contrivance, except that of the eye, it would be alone sufficient to support the conclusion which we draw from it, as to the necessity of an intelligent Creator.“

Parts of the eye: 1. vitreous body 2. ora serrata 3. ciliary muscle 4. ciliary zonules 5. canal of Schlemm 6. pupil 7. anterior chamber 8. cornea 9. iris 10. lens cortex 11. lens nucleus 12. ciliary process 13. conjunctiva 14. inferior oblique muscle 15. inferior rectus muscle 16. medial rectus muscle 17. retinal arteries and veins 18. optic disc 19. dura mater 20. central retinal artery 21. central retinal vein 22. optic nerve 23. vorticose vein 24. bulbar sheath 25. macula 26. fovea 27. sclera 28. choroid 29. superior rectus muscle 30. retina. Image courtesy of Chabacano and Wikipedia.

Fact: As I demonstrated in my reply to Myth One above, Paley never likened the universe to a watch, so the objection against his watch analogy for the cosmos rests on a false premise.

As regards the organs of living things, Paley did indeed compare them to watches, but as I pointed out in my response to Myth Two above, Paley did not declare that the complex organs found in living things are like artifacts; rather, he says that they are the same as artifacts in certain vital respects. In particular, these complex organs share several common properties with artifacts: “properties, such as relation to an end, relation of parts to one another, and to a common purpose” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 413).

In a telling passage, Paley compares the eye to a telescope, and argues that despite the evident dissimilarities between the two, their common possession of the three properties described above, which characterize what he calls contrivances, warrants the inference that they were both intelligently designed:

As far as the examination of the instrument goes, there is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision, as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it…

To some it may appear a difference sufficient to destroy all similitude between the eye and the telescope, that the one is a perceiving organ, the other an unperceiving instrument. The fact is, that they are both instruments. And, as to the mechanism, at least as to mechanism being employed, and even as to the kind of it, this circumstance varies not the analogy at all. For observe, what the constitution of the eye is. It is necessary, in order to produce distinct vision, that an image or picture of the object be formed at the bottom of the eye. Whence this necessity arises, or how the picture is connected with the sensation, or contributes to it, it may be difficult, nay we will confess, if you please, impossible for us to search out. But the present question is not concerned in the inquiry…

In the example before us, it is a matter of certainty, because it is a matter which experience and observation demonstrate, that the formation of an image at the bottom of the eye is necessary to perfect vision… The formation then of such an image being necessary (no matter how) to the sense of sight, and to the exercise of that sense, the apparatus by which it is formed is constructed and put together, not only with infinitely more art, but upon the self-same principles of art, as in the telescope or the camera obscura. The perception arising from the image may be laid out of the question; for the production of the image, these are instruments of the same kind. The end is the same; the means are the same. The purpose in both is alike; the contrivance for accomplishing that purpose is in both alike. The lenses of the telescope, and the humours of the eye, bear a complete resemblance to one another, in their figure, their position, and in their power over the rays of light, viz. in bringing each pencil to a point at the right distance from the lens; namely, in the eye, at the exact place where the membrane is spread to receive it. How is it possible, under circumstances of such close affinity, and under the operation of equal evidence, to exclude contrivance from the one; yet to acknowledge the proof of contrivance having been employed, as the plainest and clearest of all propositions, in the other?

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter III, pp. 18-21)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Six: Paley failed to address the argument that the numerous defects that we find in the organs of living things constitute powerful evidence against the hypothesis that they were designed by an Intelligent Creator.

Fact: Paley addressed this objection in the very first chapter of his Natural Theology, where he argued that someone who came across a watch lying in a field would still infer that it was designed, even if it contained defects. A badly designed object is still a designed object. In Chapter V, he returned to the objection, and allowed that imperfections might call God’s skill, power or benevolence into question, but even so, countervailing evidence that convincingly attests to God’s omniscience, omnipotence and omnibenevolence could outweigh the evidence against God’s wisdom, power and goodness from the natural evils we observe in the world:

Neither, secondly, would it invalidate our conclusion, that the watch sometimes went wrong, or that it seldom went exactly right. The purpose of the machinery, the design, and the designer, might be evident, and in the case supposed would be evident, in whatever way we accounted for the irregularity of the movement, or whether we could account for it or not. It is not necessary that a machine be perfect, in order to show with what design it was made: still less necessary, where the only question is, whether it were made with any design at all.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter I, pp. 4-5)

When we are inquiring simply after the existence of an intelligent Creator, imperfection, inaccuracy, liability to disorder, occasional irregularities, may subsist in a considerable degree, without inducing any doubt into the question: just as a watch may frequently go wrong, seldom perhaps exactly right, may be faulty in some parts, defective in some, without the smallest ground of suspicion from thence arising that it was not a watch; not made; or not made for the purpose ascribed to it…

Irregularities and imperfections are of little or no weight in the consideration, when that consideration relates simply to the existence of a Creator. When the argument respects his attributes, they are of weight; but are then to be taken in conjunction … with the unexceptionable evidences which we possess, of skill, power, and benevolence, displayed in other instances; which evidences may, in strength; number, and variety, be such, and may so overpower apparent blemishes, as to induce us, upon the most reasonable ground, to believe, that these last ought to be referred to some cause, though we be ignorant of it, other than defect of knowledge or of benevolence in the author.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter V, pp. 56-58)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Seven: Paley’s Intelligent Designer would still have to be complex, which means that on Paley’s own logic, He would need to be designed, too.

Fact: Paley was well-aware of Hume’s “infinite regress” objection, which has been popularized in our own day by Professor Richard Dawkins. He refuted it by denying its initial premise: he contended that the Designer must be immaterial and could not be composed of any complex contrivance of parts. Thus Paley’s Designer is an immaterial, simple Being:

Of this however we are certain, that whatever the Deity be, neither the universe, nor any part of it which we see, can be He. The universe itself is merely a collective name: its parts are all which are real; or which are things. Now inert matter is out of the question: and organized substances include marks of contrivance. But whatever includes marks of contrivance, whatever, in its constitution, testifies design, necessarily carries us to something beyond itself, to some other being, to a designer prior to, and out of, itself. No animal, for instance, can have contrived its own limbs and senses; can have been the author to itself of the design with which they were constructed. That supposition involves all the absurdity of self-creation, i. e. of acting without existing. Nothing can be God, which is ordered by a wisdom and a will, which itself is void of; which is indebted for any of its properties to contrivance ab extra. The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see. Which consideration contains the answer to a question that has sometimes been asked, namely, Why, since something or other must have existed from eternity, may not the present universe be that something? The contrivance perceived in it, proves that to be impossible. Nothing contrived, can, in a strict and proper sense, be eternal, forasmuch as the contriver must have existed before the contrivance.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412).

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Eight: Paley fails to address Hume’s objection that in our experience, intelligent designers are always embodied beings, so the Intelligent Designer of Nature would need to be one, too.

Fact: Paley put forward two arguments for God’s spirituality in his Natural Theology. First, he argued (following the opinion of most scientists of his day), that matter is essentially inert, in the sense that it is unable to make something move, unless something else first moves it. It follows that the ultimate source of motion in the cosmos must be something immaterial, or spiritual:

“Spirituality” expresses an idea, made up of a negative part, and of a positive part. The negative part consists in the exclusion of some of the known properties of matter, especially of solidity, of the vis inertiae, and of gravitation. The positive part comprises perception, thought, will, power, action, by which last term is meant, the origination of motion; the quality, perhaps, in which resides the essential superiority of spirit over matter, “which cannot move, unless it be moved; and cannot but move, when impelled by another (Note: Bishop Wilkins’s Principles of Natural Religion, p. 106.).” I apprehend that there can be no difficulty in applying to the Deity both parts of this idea.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 448).

Second, Paley contended that the Designer of Nature could not be composed of any matter that was organized into contrivances made up of interacting parts, because then He would have to have been designed by some entity outside Himself, which would mean that He would no longer be self-existent:

Of this however we are certain, that whatever the Deity be, neither the universe, nor any part of it which we see, can be He. The universe itself is merely a collective name: its parts are all which are real; or which are things. Now inert matter is out of the question: and organized substances include marks of contrivance. But whatever includes marks of contrivance, whatever, in its constitution, testifies design, necessarily carries us to something beyond itself, to some other being, to a designer prior to, and out of, itself. No animal, for instance, can have contrived its own limbs and senses; can have been the author to itself of the design with which they were constructed. That supposition involves all the absurdity of self-creation, i. e. of acting without existing. Nothing can be God, which is ordered by a wisdom and a will, which itself is void of; which is indebted for any of its properties to contrivance ab extra. The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412).

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Nine: Paley’s Design argument fails to establish that there’s only one designer of Nature.

Fact: In his Natural Theology, Paley argued that the uniformity of the laws of Nature constituted the best evidence of the Creator’s unity. The laws of physics are uniform throughout the entire cosmos, while the laws of biology are the same everywhere, within the Earth’s biosphere:

Of the “Unity of the Deity,” the proof is, the uniformity of plan observable in the universe. The universe itself is a system; each part either depending upon other parts, or being connected with other parts by some common law of motion, or by the presence of some common substance. One principle of gravitation causes a stone to drop towards the earth, and the moon to wheel round it. One law of attraction carries all the different planets about the sun. This philosophers demonstrate. There are also other points of agreement amongst them, which may be considered as marks of the identity of their origin, and of their intelligent author. In all are found the conveniency and stability derived from gravitation…

In our own globe, the case is clearer. New countries are continually discovered, but the old laws of nature are always found in them: new plants perhaps, or animals, but always in company with plants and animals which we already know; and always possessing many of the same general properties. We never get amongst such original, or totally different, modes of existence, as to indicate, that we are come into the province of a different Creator, or under the direction of a different will. In truth, the same order of things attend us, wherever we go.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXV, pp. 449-450)

The works of nature want only to be contemplated… We have proof, not only of both these works proceeding from an intelligent agent, but of their proceeding from the same agent; for, in the first place, we can trace an identity of plan, a connexion of system, from Saturn to our own globe: and when arrived upon our globe, we can, in the second place, pursue the connexion through all the organized, especially the animated, bodies which it supports. We can observe marks of a common relation, as well to one another, as to the elements of which their habitation is composed. Therefore one mind hath planned, or at least hath prescribed, a general plan for all these productions. One Being has been concerned in all.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, pp. 540-541)

To sum up: Paley believed he had refuted Hume’s argument that for all we know, there might be many designers, as polytheism supposes.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Ten: Paley’s God in his Natural Theology was only required to wind up the clockmaker universe at the beginning; after that, He is redundant, so we can’t be sure if He still exists or not.

Fact: This is a commonly repeated criticism of Paley’s watchmaker argument. However, what many people do not realize is that Paley anticipated this very criticism in his Natural Theology, and vigorously rebutted it.

For Paley, laws and mechanisms are incapable of explaining anything, in the absence of an agent

The first flaw in the critic’s argument is that it assumes that a law or mechanism, once established, suffices to explain how things work, and require no further explanation. As Paley pointed out, laws and mechanisms are incapable of explaining anything, in the absence of agency:

A law presupposes an agent, for it is only the mode according to which an agent proceeds; it implies a power, for it is the order according to which that power acts. Without this agent, without this power, which are both distinct from itself, the “law” does nothing; is nothing.

What has been said concerning “law,” holds true of mechanism. Mechanism is not itself power. Mechanism, without power, can do nothing.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 416)Neither mechanism, therefore, in the works of nature, nor the intervention of what are called second causes (for I think that they are the same thing), excuses the necessity of an agent distinct from both.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 419)

The watch and the hand mill: two analogies used by Paley to illustrate the world’s continual dependence on God

A human-powered treadmill, used for grinding wheat or corn. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In his book, Natural Theology, William Paley used the image of a human-powered grinding mill as an analogy for the continual dependence of the universe on the power of God, who upholds it. Paley’s analogy of the grinding mill is clearer than his watch analogy, because it is obvious that it requires the continual activity of an intelligent agent to keep it moving.

Paley used two analogies to illustrate his claim that the cosmos requires the continual activity of a living God to keep it functioning: that of a watch and that of a grinding mill (illustrated above).

Let a watch be contrived and constructed ever so ingeniously; be its parts ever so many, ever so complicated, ever so finely wrought or artificially put together, it cannot go without a weight or spring, i.e. without a force independent of, and ulterior to, its mechanism… By inspecting the watch, even when standing still, we get a proof of contrivance, and of a contriving mind, having been employed about it. In the form and obvious relation of its parts, we see enough to convince us of this… But, when we see the watch going, we see proof of another point, viz. that there is a power somewhere, and somehow or other, applied to it; a power in action;–that there is more in the subject than the mere wheels of the machine;–that there is a secret spring, or a gravitating plummet;–in a word, that there is force, and energy, as well as mechanism.

So then, the watch in motion establishes to the observer two conclusions: One; that thought, contrivance, and design, have been employed in the forming, proportioning, and arranging of its parts; and that whoever or wherever he be, or were, such a contriver there is, or was: The other; that force or power, distinct from mechanism, is, at this present time, acting upon it. If I saw a hand-mill even at rest, I should see contrivance: but if I saw it grinding, I should be assured that a hand was at the windlass, though in another room. It is the same in nature. In the works of nature we trace mechanism; and this alone proves contrivance: but living, active, moving, productive nature, proves also the exertion of a power at the centre: for, wherever the power resides, may be denominated the centre.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, pages 416-418.)

First, Paley appeals to the illustration of a watch to argue that the Designer of Nature must still be alive and active in the cosmos. The contrivances that we see in Nature tell us that it had a Designer, but it is the movement of the cosmos that tells us that the Designer must still be alive and active in the world.

Second, Paley’s analogy of the human-powered grinding mill illustrates the way in which the cosmos requires the continual activity of an intelligent agent (God) to keep it moving.

Why Paley believed that God was needed to keep the cosmos moving

To the modern reader, it may appear that Paley’s watch analogy overlooks a rather obvious objection: watches, when wound up, can continue running for a very long time without further intervention from their maker, and a hypothetical perfect watch, once constructed, might continue running throughout the duration of the cosmos. Thus it seems that Paley’s argument fails to establish the existence of a God Who is still living; all it shows is that the cosmos once had a Designer, Who may or may not still be alive.

The answer to this objection is that Paley and his contemporaries shared a common belief about matter that no longer strikes us as self-evident: namely, that a material object is incapable of making another object move unless something else moves it. Thus in Chapter XXIV of his Natural Theology, entitled, Of the Natural Attributes of the Deity, Paley refers (on page 448) to “the origination of motion; the quality, perhaps, in which resides the essential superiority of spirit over matter, ‘which cannot move, unless it be moved; and cannot but move, when impelled by another (Note: Bishop Wilkins’s Principles of Natural Religion, p. 106.).'” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, p. 448).

Again, in Chapter XXIII, Of the Personality of the Deity, when discussing the nature of the Deity, Paley writes that whatever the Deity may be, “inert matter is out of the question” (Paley, W. Natural Theology: or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412).

We can now trace the logic of Paley’s argument for a preserving Cause of the cosmos’ motion. Since bodies are incapable of initiating motion, Paley concludes that the bodies in the cosmos can only act upon each other if something immaterial is continually acting on them. We also find that bodies throughout the natural world whose parts are arranged in a complex manner, enabling them to work together for a common end. Experience tells us that intelligent agency is the only cause which is capable of producing systems with this combination of properties. From this, we may deduce that the Immaterial Agent that keeps the world moving is also an Intelligent Agent. In Paley’s words: “In the works of nature we trace mechanism; and this alone proves contrivance: but living, active, moving, productive nature, proves also the exertion of a power at the centre: for, wherever the power resides, may be denominated the centre” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 418).

Paley thought his design argument worked perfectly well, even if the universe had no beginning (and hence, no initial “wind-up”)

A final problem with the objection that all Paley’s argument establishes is the existence of an Divine Watchmaker Who wound up the cosmos at the beginning (and Who may no longer be alive) is that it assumes Paley thought he could prove the universe had a beginning. In fact, he argued that even if it were eternal, it would still require a Designer:

Nor is any thing gained by running the difficulty farther back, i. e. by supposing the watch before us to have been produced from another watch, that from a former, and so on indefinitely. Our going back ever so far, brings us no nearer to the least degree of satisfaction upon the subject. Contrivance is still unaccounted for. We still want a contriver. A chain, composed of an infinite number of links, can no more support itself, than a chain composed of a finite number of links. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter II, pp. 12-13.)

The machine which we are inspecting, demonstrates, by its construction, contrivance and design. Contrivance must have had a contriver; design, a designer; whether the machine immediately proceeded from another machine or not. That circumstance alters not the case. That other machine may, in like manner, have proceeded from a former machine: nor does that alter the case; contrivance must have had a contriver. That former one from one preceding it: no alteration still; a contriver is still necessary. No tendency is perceived, no approach towards a diminution of this necessity. It is the same with any and every succession of these machines; a succession of ten, of a hundred, of a thousand; with one series, as with another; a series which is finite, as with a series which is infinite. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter II, pp. 13-14.)

Our observer would further also reflect, that the maker of the watch before him, was, in truth and reality, the maker of every watch produced from it; there being no difference (except that the latter manifests a more exquisite skill) between the making of another watch with his own hands, by the mediation of files, lathes, chisels, &c. and the disposing, fixing, and inserting of these instruments, or of others equivalent to them, in the body of the watch already made in such a manner, as to form a new watch in the course of the movements which he had given to the old one. It is only working by one set of tools, instead of another. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XII, p. 16.)

For Paley, the Designer of Nature is the Cause of existence of everything in Nature

The final and decisive refutation of the claim that Rev. William Paley only argued for a Deity that wound up the universe at the beginning is that there are passages in his Natural Theology, where he explicitly declares God to be the cause of existence of everything in Nature:

… I shall not, I believe, be contradicted when I say, that, if one train of thinking be more desirable than another, it is that which regards the phenomena of nature with a constant reference to a supreme intelligent Author. To have made this the ruling, the habitual sentiment of our minds, is to have laid the foundation of every thing which is religious. The world thenceforth becomes a temple, and life itself one continued act of adoration. The change is no less than this, that, whereas formerly God was seldom in our thoughts, we can now scarcely look upon any thing without perceiving its relation to him. Every organized natural body, in the provisions which it contains for its sustentation and propagation, testifies a care, on the part of the Creator, expressly directed to these purposes. We are on all sides surrounded by such bodies; examined in their parts, wonderfully curious; compared with one another, no less wonderfully diversified.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, p. 539)

Against not only the cold, but the want of food, which the approach of winter induces, the Preserver of the world has provided in many animals by migration, in many others by torpor.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XVII, p. 298)

Under this stupendous Being we live. Our happiness, our existence, is in his hands. All we expect must come from him.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, p. 541)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Eleven: Paley’s God in his Natural Theology is an impersonal Designer, and not the God of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Fact: Paley’s work was entitled Natural Theology, so it is hardly surprising that he does not explicitly argue for the existence of the God of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Nevertheless, Paley argued that God must be a personal Being, because He is capable of designing things. As he put it: “that which can contrive, which can design, must be a person” (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 408). A designer, by definition, possesses consciousness and thought, and must be capable of perceiving a goal or end, and adapting and directing means to achieve this goal. Such a being, Paley argued, must be a person (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, pp. 408, 441).

In addition to being personal, Paley argued in his Natural Theology that the Designer of Nature must be:

(a) transcendent, because “contrivances” [systems composed of parts working together for a common end] are found at all levels throughout Nature, so their Author must lie beyond Nature;

(b) uncaused, or self-existent, because His existence does not have any preceding cause;

(c) the cause not only of the origin of things, but of their continuation in existence, because the physical laws which define their very natures, could only have been chosen by an intelligent agent, and because these laws only continue to hold by virtue of the ongoing activity of this intelligent agent;

(d) one, because the uniformity of His plan can be seen throughout Nature;

(e) spiritual, because He is a personal agent capable of thought and will, and capable (unlike matter) of moving things without needing anyone to move Him;

(f) good, because the contrivances He has placed in living things are designed for the good of those creatures, and not for their harm;

(g) omnipresent, because His power extends throughout Nature;

(h) omnipotent, because everything is His handiwork, so there is nothing to limit His power over Nature;

(i) omniscient, because the knowledge required for the formation of created nature is infinite, since He selected the laws of the cosmos from an infinite range of possible options;

(j) simple, because complex beings require an external cause for the skillful contrivance of their parts, whereas God has no cause;

(k) beyond space and time, since He is their Author, and has no limits. (One could draw the conclusion, though Paley himself does not explicitly say so, that God is therefore timeless and immutable.)

In all these respects, Paley’s God is identical with the God of classical theism. On two points, however, Paley differs from most classical theists.

First, Paley equates the necessity of God with the possibility of our demonstrating His existence, whereas for classical theists, God’s necessity is usually grounded in the notion that God is Pure Existence, and hence incapable of non-existence.

Second, Paley appears to believe that God is capable of perceiving the world in some way. Even if this perception occurs timelessly in the mind of God, it would still mean that He is passible, or capable of being affected by the world. Classical theism, however, traditionally holds that God is impassible. However, neither the necessity nor the impassibility of God forms part of the defined teachings of Judaism, Christianity or Islam. None of these religions teach that God is Pure Existence. Nor do they teach that God is impassible, or incapable of being affected by His creatures; rather, what they teach is that God does not have passions, or bodily feelings.

I conclude that Paley falls within the broad tradition of classical theism, albeit of a very pragmatic variety, insofar as he endeavors to explain the Divine attributes in terms of how they affect us, rather than describing them in terms of God’s inner being – a subject about which Paley prefers not to speculate.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Myth Twelve: At most, Paley’s design argument establishes only the existence of a finite, limited Deity, which falls short of the Infinite God of classical theism.

Fact: A careful examination of Paley’s writings shows that he put forward no less than four arguments for God’s infinity, in his Natural Theology. Some of these arguments are better than others, but they certainly show that Paley was well aware of Hume’s objection that the design argument could only establish the existence of a finite God, and that he vigorously endeavored to refute it.

First, using the example of the eye, Paley argued that God’s designs are infinitely more skillful than our own (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter III, p. 21).

We can also discern a second argument for God’s infinite intelligence in Paley’s observation that when God selected the laws of Nature, He had to make a choice from among an infinite number of alternatives, only an infinitesimal proportion of which were compatible with the formation of a stable cosmos (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXII, p. 393).

Third, Paley argued that God must be infinitely powerful, because He is able to control an indefinitely large region of space by His volitions: His power extends everywhere.

Fourth, Paley considered that God must be infinitely wise, because He is apparently capable of manifesting His wisdom and benevolence in an unlimited number of ways, and upon an unlimited number of objects (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVI, p. 492; Chapter XXVII, p. 548).

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Did Paley’s argument take into account the fact that organisms reproduce?

|

|

Left: Hoverflies mating in midair flight. Image courtesy of Fir0002/Flagstaffotos and Wikipedia.

Right: The sexual cycle. Image courtesy of UserStannered and Wikipedia.

Perhaps the silliest myth about Paley’s Natural Theology is that he overlooked a rather obvious dissimilarity between living things and artifacts: that living things reproduce and are therefore capable of gradually improving or refining their design, whereas artifacts such as watches don’t reproduce, which is why they are utterly incapable of improving their design on a step-by-step basis. The fact is that Paley spent four whole pages refuting this argument in Chapter II of his book, where he imagines what a person would rationally infer, if he found a watch that was capable of making a copy of itself:

Suppose, in the next place, that the person who found the watch, should, after some time, discover that, in addition to all the properties which he had hitherto observed in it, it possessed the unexpected property of producing, in the course of its movement, another watch like itself (the thing is conceivable); that it contained within it a mechanism, a system of parts, a mould for instance, or a complex adjustment of lathes, files, and other tools, evidently and separately calculated for this purpose; let us inquire, what effect ought such a discovery to have upon his former conclusion.

I. The first effect would be to increase his admiration of the contrivance, and his conviction of the consummate skill of the contriver. Whether he regarded the object of the contrivance, the distinct apparatus, the intricate, yet in many parts intelligible mechanism, by which it was carried on, he would perceive, in this new observation, nothing but an additional reason for doing what he had already done, — for referring the construction of the watch to design, and to supreme art. If that construction without this property, or which is the same thing, before this property had been noticed, proved intention and art to have been employed about it; still more strong would the proof appear, when he came to the knowledge of this further property, the crown and perfection of all the rest.

II. He would reflect, that though the watch before him were, in some sense, the maker of the watch, which was fabricated in the course of its movements, yet it was in a very different sense from that, in which a carpenter, for instance, is the maker of a chair; the author of its contrivance, the cause of the relation of its parts to their use. With respect to these, the first watch was no cause at all to the second: in no such sense as this was it the author of the constitution and order, either of the parts which the new watch contained, or of the parts by the aid and instrumentality of which it was produced. We might possibly say, but with great latitude of expression, that a stream of water ground corn: but no latitude of expression would allow us to say, no stretch of conjecture could lead us to think, that the stream of water built the mill, though it were too ancient for us to know who the builder was. What the stream of water does in the affair, is neither more nor less than this; by the application of an unintelligent impulse to a mechanism previously arranged, arranged independently of it, and arranged by intelligence, an effect is produced, viz. the corn is ground. But the effect results from the arrangement. The force of the stream cannot be said to be the cause or author of the effect, still less of the arrangement. Understanding and plan in the formation of the mill were not the less necessary, for any share which the water has in grinding the corn: yet is this share the same, as that which the watch would have contributed to the production of the new watch, upon the supposition assumed in the last section. Therefore,

III. Though it be now no longer probable, that the individual watch, which our observer had found, was made immediately by the hand of an artificer, yet doth not this alteration in anywise affect the inference, that an artificer had been originally employed and concerned in the production. The argument from design remains as it was. Marks of design and contrivance are no more accounted for now, than they were before. In the same thing, we may ask for the cause of different properties. We may ask for the cause of the colour of a body, of its hardness, of its head; and these causes may be all different. We are now asking for the cause of that subserviency to a use, that relation to an end, which we have remarked in the watch before us. No answer is given to this question, by telling us that a preceding watch produced it. There cannot be design without a designer; contrivance without a contriver; order without choice; arrangement, without any thing capable of arranging; subserviency and relation to a purpose, without that which could intend a purpose; means suitable to an end, and executing their office, in accomplishing that end, without the end ever having been contemplated, or the means accommodated to it. Arrangement, disposition of parts, subserviency of means to an end, relation of instruments to a use, imply the presence of intelligence and mind. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter II, pp. 8-11)

Later on in his book, Paley fleshed out his argument that reproduction, while teleological, is also a mechanical process, which still requires the existence of an Intelligent Designer:

The generation of the animal no more accounts for the contrivance of the eye or ear, than, upon the supposition stated in a preceding chapter, the production of a watch by the motion and mechanism of a former watch, would account for the skill and intention evidenced in the watch, so produced; than it would account for the disposition of the wheels, the catching of their teeth, the relation of the several parts of the works to one another, and to their common end, for the suitableness of their forms and places to their offices, for their connexion, their operation, and the useful result of that operation. I do insist most strenuously upon the correctness of this comparison; that it holds as to every mode of specific propagation; and that whatever was true of the watch, under the hypothesis above-mentioned, is true of plants and animals… Has the plant which produced the seed any thing more to do with that organization, than the watch would have had to do with the structure of the watch which was produced in the course of its mechanical movement? I mean, Has it any thing at all to do with the contrivance? The maker and contriver of one watch, when he inserted within it a mechanism suited to the production of another watch, was, in truth, the maker and contriver of that other watch. All the properties of the new watch were to be referred to his agency: the design manifested in it, to his intention: the art, to him as the artist: the collocation of each part to his placing: the action, effect, and use, to his counsel, intelligence, and workmanship. In producing it by the intervention of a former watch, he was only working by one set of tools instead of another. So it is with the plant, and the seed produced by it.

Can any distinction be assigned between the two cases; between the producing watch, and the producing plant; both passive, unconscious substances; both by the organization which was given to them, producing their like, without understanding or design; both, that is, instruments?

From plants we may proceed to oviparous animals; from seeds to eggs. Now I say, that the bird has the same concern in the formation of the egg which she lays, as the plant has in that of the seed which it drops; and no other, nor greater. The internal constitution of the egg is as much a secret to the hen, as if the hen were inanimate… Although, therefore, there be the difference of life and perceptivity between the animal and the plant, it is a difference which enters not into the account. It is a foreign circumstance. It is a difference of properties not employed. The animal function and the vegetable function are alike destitute of any design which can operate upon the form of the thing produced. The plant has no design in producing the seed, no comprehension of the nature or use of what it produces: the bird with respect to its egg, is not above the plant with respect to its seed. Neither the one nor the other bears that sort of relation to what proceeds from them, which a joiner does to the chair which he makes.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter IV, pp. 49-52)

Finally, Paley denounced the intellectual laziness of skeptical philosophers in his day, who were fond of invoking self-replication as an explanation for biological complexity, while failing to advert to the obvious fact that an organism’s reproductive system is itself a contrivance of parts working together towards a common end, and that such a contrivance must have had an Intelligent Designer:

The minds of most men are fond of what they call a principle, and of the appearance of simplicity, in accounting for phenomena. Yet this principle, this simplicity, resides merely in the name; which name, after all, comprises, perhaps, under it a diversified, multifarious, or progressive operation, distinguishable into parts. The power in organized bodies, of producing bodies like themselves, is one of these principles. Give a philosopher this, and he can get on. But he does not reflect, what this mode of production, this principle (if such he choose to call it) requires; how much it presupposes; what an apparatus of instruments, some of which are strictly mechanical, is necessary to its success; what a train it includes of operations and changes, one succeeding another, one related to another, one ministering to another; all advancing, by intermediate, and, frequently, by sensible steps, to their ultimate result!

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, pp. 420-421)

While we’re on the subject of reproduction, I’d strongly recommend that readers take a look at Kairosfocus’ excellent post, The ghost of William Paley speaks — Stephen Meyer’s minimalist case for intelligent design in the face of claims that Hume and Darwin had refuted it, which discusses the mechanics of reproduction in great detail from an origin-of-life perspective.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

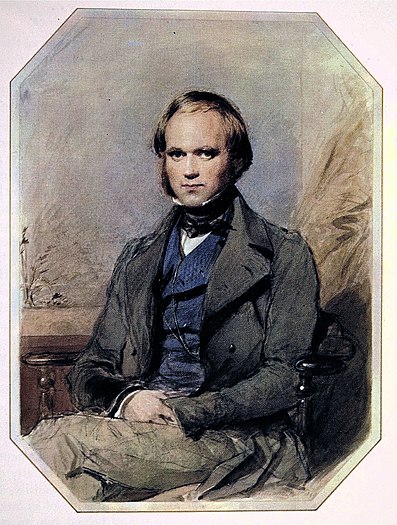

Did Darwin refute Paley’s argument?

|

Portrait of Charles Darwin, by George Richmond. Late 1830s. Image courtesy of Richard Leakey, Roger Lewin and Wikipedia.

Neo-Darwinists often claim that Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species, published in 1859, decisively refuted Paley’s argument for a Designer, once and for all. For my part, I think Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection made a relatively minor dent in Paley’s case.