For the past several weeks, there has been an exchange that developed in the eduction vs persuasion thread (put up May 9th by AndyJones), on first principles of right reason and related matters. Commenter RDF . . . has championed some popular talking points in today’s intellectual culture.

We can therefore pick up from a citation and comment by Vivid, at 619 in the thread (June 12th), for record and possible further discussion.

Accordingly, I clip comment 742 from the thread (overnight) and headline it:

_____________

>>. . . let us remind ourselves of the context for the just above exchanges, by going back to Vivid at 619:

[RDF/AIG:] And once again I must remind you that you are mistaken. We cannot be absolutely certain of anything, and you will see that I have never said that we could be absolutely certain of anything. I don’t think this is a very difficult point, but you keep misquoting me.

[Vivid, replying:} I apologize I did not intend to misquote you I now understand your position better. You are not absolutely certain that there is no such thing as absolute certainty but you want Stephen[B] to concede to that which you are not absolutely certain about. Got it.

Notice, this is what RDF has to defend, cited from his own mouth:

[RDF:] We cannot be absolutely certain of anything . . .

This absolute declaration of certainty that we cannot be certain of anything, aptly exposes the underlying incoherence of what RDF has been arguing.

He has spent much time trying to ignore a sound worldviews foundation approach, and has sought to undermine first principles of right reason in order to advance an agenda that from its roots on up, is incoherent.

So, let it be understood that when reason was in the balance, he was found wanting, decisively wanting. Again and again.

In particular, observe his willful unresponsiveness to and “passive” resistance by that unresponsiveness, to the basic point that by direct case, Royce’s Error exists, we can show that there are truths that are generally recognised, are accessible to our experiences, are factually grounded, and can be shown to be undeniably true and self evident, constituting certain knowledge of the world of things in themselves accessible to humans.

Thus, his whole project of want of grounding for reasoning and building worldviews collapses from the foundations.

In particular, observe as well that he has for hundreds of comments, waged an ideological talking point war against cause and effect, trying to poison the atmosphere to disguise the want of a good basis for rejecting it.

For instance, observe how he has never seriously engaged the point that once a thing A exists, following Schopenhauer, we may freely ask, why and expect to find a reasonable, intelligible answer. (This is in part a major basis for science, and also for philosophy.)

This principle, sufficient reason, is patently reasonable and self-evident: that if A is, there is a good explanatory reason for it.

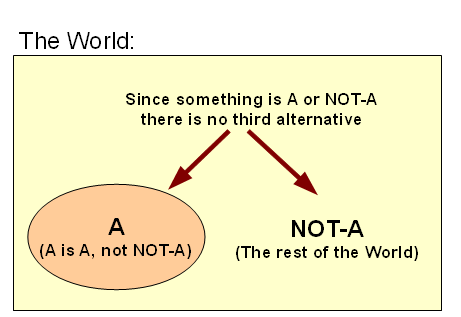

First, that A’s attributes, unlike those of a square circle, are coherent. So, from this point on, the law of non-contradiction is inextricably entangled int he possibility of being. Consequently we see the antithesis: possibility vs impossibility of being.

Next, by virtue of possible worlds analysis, we can distinguish another antithesis: contingent vs non-contingent (i.e. NECESSARY) beings.

That is, we can have possible worlds in which certain things — contingent beings, C — could exist and others in which C does not exist. For instance, a horned horse is obviously a possible being but happens not to exist as of yet in the actual world we inhabit. But it is conceivable that within a century, through genetic engineering, one may well exist. (I am not so sure that they will be able to make a pink one, but a white one is very conceivable.)

We are of course just such members of class C.

(And this wider class C further opens the way to significant choice by humans, by which we can imagine possible futures, and by rational evaluation of the consequences of our ideas, models and plans, decide which to implement, e.g. by choosing a design of the building to replace the WTC buildings in NYC knocked down by Bin Laden and co on Sept 11, 2001 — a date chosen by him on the probable grounds that it was the 318th anniversary less one day, from the great cavalry attack led by Jan III Sobieski of Poland and Lithuania, which broke the final Turkish siege of Vienna under the Caliph at that time in 1683. That is, by choosing the day, UBL was making a message to his fellow radicalised Muslims that he was taking over from the previous high-water mark of IslamIST expansionism. And that he was doing so in the general area of Khorasan would also be of significance to such Muslims, who would immediately recognise the significance and relevance of black flag armies from that general area. I give these examples, to underscore the significance of contingency and intelligent, willed choice in humans, something that RDF/AIG also wishes to undermine. He does not see the fatal self-referential incoherence that stems from that, and doubtless would dismiss the significance of incoherence as well. The circle of ideological irrationality driven by a priori evolutionary materialism and its fellow traveller ideas and agendas, closes.)

But C has its antithesis in a world partition, class NOT-C; let us call it N.

Necessary beings, such as the number two, 2 or the true proposition 2 + 3 = 5, etc.

Public domain

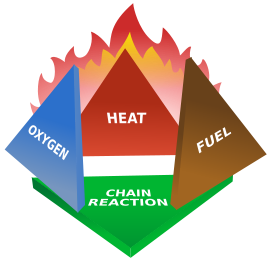

Public domainMembers of C are marked by dependence on ON/OFF enabling factors, e.g. as we have frequently discussed, how a match flame depends on each of: heat, fuel, oxidiser and chain reaction. Such enabling factors are necessary causal factors, all of which must be present for a member of class C to be actualised. A sufficient condition for such a member will have at least all of the factors like this, met.

We naturally and reasonably say that such a member of C is CAUSED when its conditions to exist are met by a sufficient cluster of factors, and that E is an effect; the cluster of factors being causes. So, even if we do not know the full set of causal factors for C, we can be confident that a contingent being, that has a beginning and may end or could conceivably not have been at all, is caused.

However, not all things are like that. Some things have no such dependence on causal factors, and are possible beings. These beings will be actual in all possible worlds, i.e. they are necessary beings.

A serious candidate necessary being will be either impossible (blocked by having incoherent proposed attributes such as a square circle), or it will be possible and actual. As noted, S5, in modal logic, captures part of why. {Cf. here.} In effect we can see that such a being just is, inevitably, and its absence would be impossible.

For example the number 2 just is. Even in an empty world, one can see that we have the empty set { } –> 0. Thence, we may form a set which collects the empty set: {0} –> 1. Then, in the next step, we simply collect both: {0, 1} –> 2. For modern set theory, we simply continue the process to get 3, 4, 5 . . . , but this is enough for our purposes. Doing this abstract analytical exercise does not create 2, it simply recognises how inevitable it is. It is impossible for 2 not to exist. Similarly, the true proposition 2 + 3 = 5 is like that, and much more besides.

We thus see that necessary beings exist and are knowable, even familiar in some cases.

We see further that such beings are without beginning, or end. They are not caused, they hold being by necessity, which its their sufficient reason for existing. They have no dependence on external enabling causal factors.

A serious candidate to be a necessary being will be independent of enabling factors, likewise (flying spaghetti monsters need not apply) and will not be composed of material parts. The abstract, thought-nature of cases like 2, 2 + 3 = 5 etc shows that such beings point to mind, and one way of accounting for such beings is that they are eternally contemplated by God. Where also God is regarded as an eternal, necessary, spiritual being who is minded and the root of all being in our world, the ultimate enabling factor for reality.

BTW, this means that those who would dismiss God’s existence do not merely need to establish that in their view God is improbable, but that God is impossible, as God is a serious candidate to be a necessary being.

That is, since RDF is so hot to undermine the intellectual credibility of the existence of God, it is worth pausing to highlight a few points on this matter, connected to the logic of necessary beings and other relevant points. For, even before we run into other things that point like compass needles to God: the evident design of a fine tuned cosmos set up for C-chemistry, aqueous medium cell based life that makes an extra cosmic, intelligent agent with power to create a cosmos the explanation to beat, the significance of our being minded and characterised by reason, as well as the existence of a world of life in that context, the fact that we inescapably find ourselves under moral government by implanted law, and of course the direct encounter with God that millions report as having positively transformed their lives, and more.

Nope, unlike the pretence of too many skeptics would lead us to naively believe, the acceptance of God’s reality is a very reasonable position to hold. (Scroll back up and observe the studious silence of RDF et al on such matters.)

So, never mind the ink-clouds of distractive or dismissive or confusing talking-points, we are back to the worldview level significance of first principles of right reason and pivotal first, self-evident truths.

{Let us add, an illustrative diagram, on how naturally these principles arise from a world-partition, e.g. by having a bright red ball on a table:}

{And,we may clip Wikipedia’s article on laws of thought:

The law of non-contradiction and the law of excluded middle are not separate laws per se, but correlates of the law of identity. That is to say, they are two interdependent and complementary principles that inhere naturally (implicitly) within the law of identity, as its essential nature . . . whenever we ‘identify’ a thing as belonging to a certain class or instance of a class, we intellectually set that thing apart from all the other things in existence which are ‘not’ of that same class or instance of a class. In other words, the proposition, “A is A and A is not ~A” (law of identity) intellectually partitions a universe of discourse (the domain of all things) into exactly two subsets, A and ~A, and thus gives rise to a dichotomy. As with all dichotomies, A and ~A must then be ‘mutually exclusive’ and ‘jointly exhaustive’ with respect to that universe of discourse. In other words, ‘no one thing can simultaneously be a member of both A and ~A’ (law of non-contradiction), whilst ‘every single thing must be a member of either A or ~A’ (law of excluded middle).

What’s more . . . thinking entails the manipulation and amalgamation of simpler concepts in order to form more complex ones, and therefore, we must have a means of distinguishing these different concepts. It follows then that the first principle of language (law of identity) is also rightfully called the first principle of thought, and by extension, the first principle reason (rational thought) . . .

Another illustration shows how world view roots arise:}

Prediction (do, prove me wrong RDF et al): this too will be studiously ignored in haste to push along with the talking point agenda. The price tag for such apparently habitual tactics, is willful neglect of duties of care to be reasonable, to seek and face truth, and to be fair in discussion.

That is, it is “without excuse.”

(And yes, the allusion to Rom 1:19 – 25 and vv. 28 – 32 is quite deliberate.) >>

____________

So, we face the issue of worldview foundations, in light of first principles of right reason.

(One that — per fair comment, for weeks now, RDF/AIG has studiously ducked, behind a cloud of talking points.)

How will we respond?

On what basis of reasoning?

With what level of certainty?

Why? END