|

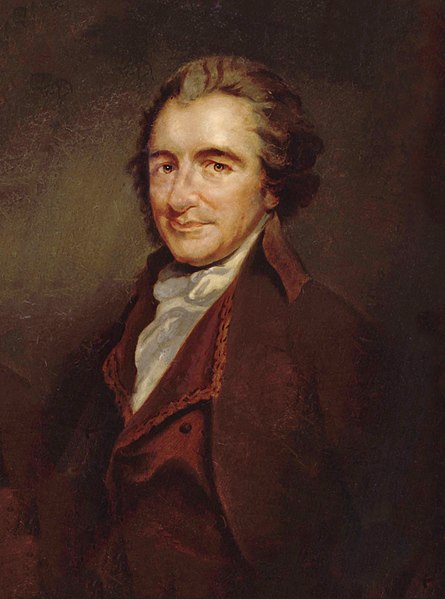

The Freedom From Religion Foundation, which bills itself as “the nation’s largest association of atheists and agnostics, working to keep religion out of government,” ran an advertisement in The New York Times on July 4, 2013 (see page A7 of the paper edition), inviting Americans to “Celebrate our Godless Constitution.” Now, I’ll say a little more about the American Constitution in a moment, but before I do, I’d like to comment on the advertisement’s quotations from the writings of Thomas Paine, Benjamin Franklin and the first four Presidents of the United States, in support of their cause.

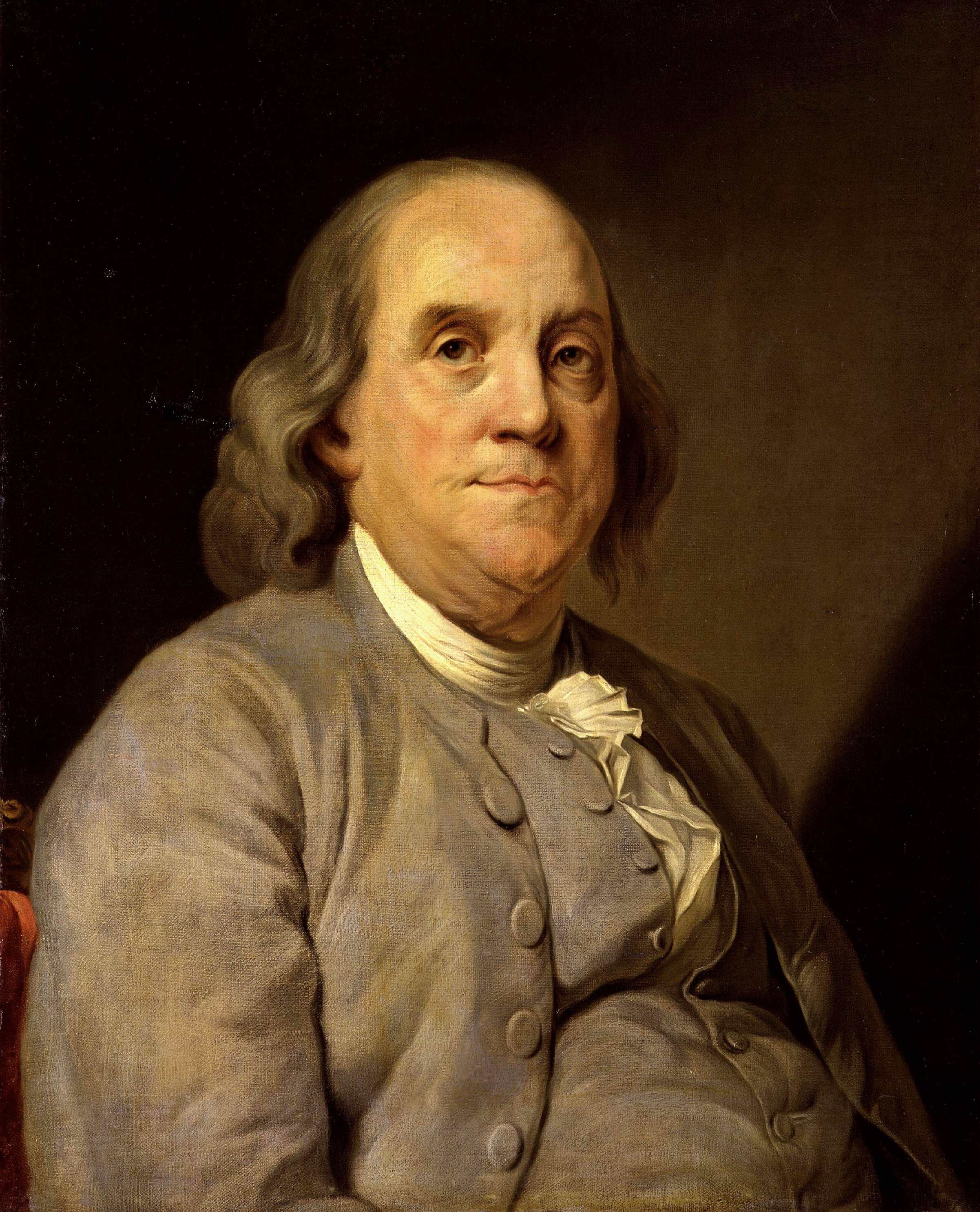

In the words of the FFRF press release accompanying the New York Times advertisement: “The ads quote U.S. Founders and Framers on their strong views against religion in government, and often critical views on religion in general. The ad features two revolutionaries and Deists, Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin, and the first four presidents: George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.”

The Freedom From Religion Foundation states in its press release that its motivation in placing the advertisement was to refute what it describes was “the myth that the United States was founded on God and Christianity.” It accuses the craft store chain Holly Lobby of propagating this myth in a series of July 4 ads sponsored annually by the chain since 2008. A copy of the latest Holly Lobby ad can be seen here.

Now, it is fair to say that at least one of the Founding Fathers (Thomas Paine) was vocally opposed to organized religion. It is also a matter of historical fact that the Fathers ardently believed that there should be no established Church, and that no church should be financially supported or assisted by the State. But it is also true to say that not one of the Founding Fathers was an agnostic or atheist. Indeed, all of them stoutly maintained that people’s rights are derived from God. For the Founding Fathers, the only firm basis of a country’s political liberties was “a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God,” as President Thomas Jefferson put it in his 1785 Notes on the State of Virginia (Query 18). What’s more, the God that Jefferson and the other Founding Fathers believed in was not an impersonal abstraction, but a just God, Who expects human beings to be both fair and charitable in their dealings with one another, and Who punishes acts of injustice. As for personal morality, President Thomas Jefferson was the only one of the Founding Fathers to explicitly declare that even a person with “a belief that there is no God” could still find “incitements to virtue,” although he went on to add that belief in God who approves of good deeds was “a vast additional incitement” to act virtuously.

When I came across the Freedom From Religion Foundation advertisement, my curiosity was piqued, and I decided to check out its claims. In this post, I intend to examine each of the quotes in the FFRF advertisement, and see how they stack up against the facts. I’ll also have something to say about the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s claim that the American Constitution is godless.

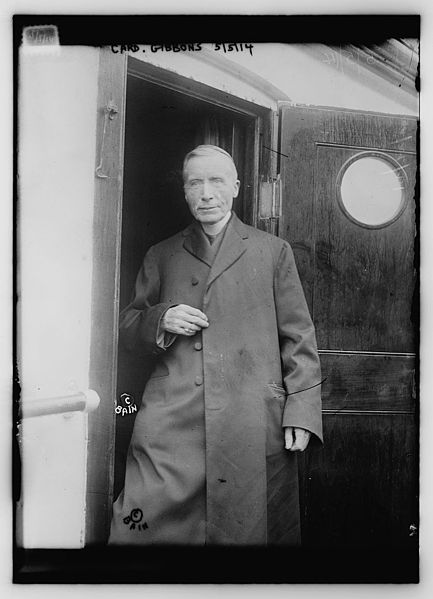

For the benefit of readers, I should mention that my own interest in American history was awakened at the age of eight, when I was living in the town of Northam, Western Australia. A kind gentleman who was also a Knight of the Southern Cross gave me a copy of a book titled, Larger than the sky: a story of James Cardinal Gibbons by Covelle Newcomb (Longmans, Green and Co., 1948). From then on, I was hooked by the drama of American history. I’ll be saying more about Cardinal Gibbons below, by the way.

Here is an executive summary of what I found, for those readers who don’t like long posts.

1. Thomas Paine

|

2. Benjamin Franklin

|

3. George Washington

|

4. John Adams

|

5. Thomas Jefferson

|

6. James Madison

|

Is America a Christian country?

|

1. Thomas Paine

|

The Freedom From Religion Foundation quote reads as follows:

Whenever we read the obscene stories, the voluptuous debaucheries, the cruel and torturous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness, with which more than half the bible is filled, it would seem more consistent that we called it the word of a demon than the Word of God. It is a history of wickedness that has served to corrupt and brutalize…

The quote is from The Age of Reason. The above extract is taken from Part First, Section 4 of the book. I find it rather amusing that the Freedom From Religion Foundation, in a fit of political correctness, omitted the word “mankind” from the end of the last clause. Paine goes on to add: “and, for my part, I sincerely detest it, as I detest everything that is cruel.”

But Paine was also an Intelligent Design fan, who believed that students studying science should be taught about how the cosmos points to a Creator. Don’t believe me? Let’s take a look at what he said in his essay, The Existence of God, which was originally a speech Paine gave at the Society of Theophilanthropists, Paris, and which was probably read at their first public meeting, on January 16, 1797. The Theophilanthropists (“Friends of God and Man”) were a Deistic sect, formed in France during the latter part of the French Revolution. An article in The Catholic Encyclopedia describes the origins of the Theophilanthropists:

The legal substitution of the Constitutional Church, the worship of reason, and the cult of the Supreme Being in place of the Catholic Religion had practically resulted in atheism and immorality. With a view to offsetting those results, some disciples of Rousseau and Robespierre resorted to a new religion, wherein Rousseau’s deism and Robespierre’s civic virtue (regne de la vertu) would be combined.

The Theophilanthropists shared two basic beliefs: they believed in God and in a hereafter. Thomas Paine believed as much, for he wrote: “I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life.” (The Age of Reason, Part First, Section 1).

Now at last we are in a position to appreciate the significance of Paine’s criticisms of the way in which the natural sciences are taught in the schools. He was speaking to a French audience, and the target of his criticisms would have been the secular science curriculum that was adopted in revolutionary France. Paine objected to this curriculum, on the grounds that teaching scientific principles without any mention of their Divine Author would dampen students’ intellectual curiosity and foster shallow thinking, which would inevitably lead to atheism:

It has been the error of the schools to teach astronomy, and all the other sciences, and subjects of natural philosophy, as accomplishments only; whereas they should be taught theologically, or with reference to the Being who is the author of them: for all the principles of science are of divine origin. Man cannot make, or invent, or contrive principles: he can only discover them; and he ought to look through the discovery to the author.

When we examine an extraordinary piece of machinery, an astonishing pile of architecture, a well executed statue, or an highly finished painting, where life and action are imitated, and habit only prevents our mistaking a surface of light and shade for cubical solidity, our ideas are naturally led to think of the extensive genius and talents of the artist. When we study the elements of geometry, we think of Euclid. When we speak of gravitation, we think of Newton. How then is it, that when we study the works of God in the creation, we stop short, and do not think of GOD? It is from the error of the schools in having taught those subjects as accomplishments only, and thereby separated the study of them from the ‘Being’ who is the author of them…

The evil that has resulted from the error of the schools, in teaching natural philosophy as an accomplishment only, has been that of generating in the pupils a species of Atheism. Instead of looking through the works of creation to the Creator himself, they stop short, and employ the knowledge they acquire to create doubts of his existence… (Emphases mine – VJT.)

So here we have Thomas Paine, a leading figure in the history of skeptical thought and a fierce critic of religion, expressly advocating the idea of bringing God back into the French science curriculum!

I can’t imagine why the Freedom From Religion Foundation would consider someone like Thomas Paine as their political ally.

2. Benjamin Franklin

|

The Freedom From Religion Foundation quote from Benjamin Franklin reads as follows:

When a Religion is good, I conceive that it will support itself; and, when it cannot support itself, and God does not take care to support it, so that its Professors are obliged to call for the help of the Civil Power, ’tis a sign, I apprehend, of its being a bad one.

The quote is taken from Franklin’s letter to Richard Price, dated October 9, 1780. It illustrates Franklin’s belief that the Church should not rely on the State for financial support. For his part, Franklin was a Deist, who felt that organized religion was necessary to keep men good to their fellow men, but he rarely attended religious services himself. (Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography, edited by J. A. Leo Lemay and P. M. Zall, W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 1986, p. 65.)

But Franklin also believed that the only good government was a God-fearing government, and that a government that failed to acknowledge its dependence on God was doomed to failure. As Secretary of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Franklin also passed a motion calling for the introduction the practice of daily common prayer, at a critical juncture when deliberations were getting bogged down:

… In the beginning of the contest with G. Britain, when we were sensible of danger we had daily prayer in this room for the Divine Protection. – Our prayers, Sir, were heard, and they were graciously answered. All of us who were engaged in the struggle must have observed frequent instances of a Superintending providence in our favor. … And have we now forgotten that powerful friend? or do we imagine that we no longer need His assistance. I have lived, Sir, a long time and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth – that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without his notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without his aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings that “except the Lord build they labor in vain that build it.” I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without his concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel: … I therefore beg leave to move – that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed to business, and that one or more of the Clergy of this City be requested to officiate in that service.

The motion met with resistance and was never brought to a vote; but it is a touching testament to Franklin’s deep personal faith in God. The fact that Franklin called for the government to hold daily prayers, which would be officiated by members of the clergy, gives the lie to the claim by the Freedom From Religion Foundation that the Founding Fathers believed that Church and State be kept completely separate from one another. What they actually believed was that there should be no legally established Church, and that churches should not be financially supported by the State.

3. George Washington, first President of the United States

|

The Freedom From Religion Foundation quote from President George Washington reads as follows:

“Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony & irreconcilable hatreds than those which spring from any other cause…”

The quote is taken from Washington’s letter to Sir Edward Newenham, dated June 22, 1792. The paragraph from which the quote is taken reads as follows:

I regret exceedingly that the disputes between the protestants and Roman Catholics should be carried to the serious alarming height mentioned in your letters. Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony and irreconcilable hatreds than those which spring from any other cause; and I was not without hopes that the enlightened and liberal policy of the present age would have put an effectual stop to contentions of this kind.

As far as I can see, the letter merely establishes that President George Washington opposed religious bigotry, not that he opposed religion.

The Freedom From Religion Foundation advertisement goes on to say that “Our first US President refused to take Communion, kneel in prayer in churches (or at Valley Forge), have a priest at his deathbed or take last rites.” The statement, as it stands, conveys the misleading impression that Washington’s behavior was motivated by either indifference to or an antipathy towards religion. This is simply not the case.

As Michael and Jana Novak point out in their book, Washington’s God: Religion, Liberty and the Father of Our Country (Basic Books, 2007, p. 97), it was not at all uncommon in those days for churchgoers to pass on participating in communion. It should be added that Washington attended church services about once a month the period 1760-1773, while he was at Mount Vernon (Ford, Paul Leicester. The True George Washington, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1897, p. 78), even though doing so required him to ride several miles (Novak & Novak, p. 97). During his tours of the nation in his two terms as President, he attended religious services more frequently, sometimes as often as three times a day (Novak & Novak, p. 39).

Washington’s religious practices: the testimony of his adopted daughter

Concerning the religious practices of George Washington, we have the eyewitness testimony of Eleanor Parke Lewis, Martha Washington’s granddaughter and George Washington’s adopted daughter. I’d like to quote a few brief excerpts from her letter on the subject, dated 26 February 1833 (emphases are mine):

General Washington had a pew in Pohick Church, and one in Christ Church at Alexandria…

He attended the church at Alexandria when the weather and roads permitted a ride of ten miles. In New York and Philadelphia he never omitted attendance at church in the morning, unless detained by indisposition. The afternoon was spent in his own room at home; the evening with his family, and without company. Sometimes an old and intimate friend called to see us for an hour or two; but visiting and visitors were prohibited for that day. No one in church attended to the services with more reverential respect. My grandmother, who was eminently pious, never deviated from her early habits. She always knelt. The General, as was then the custom, stood during the devotional parts of the service. On communion Sundays, he left the church with me, after the blessing, and returned home, and we sent the carriage back for my grandmother…

…I never witnessed his private devotions. I never inquired about them. I should have thought it the greatest heresy to doubt his firm belief in Christianity. His life, his writings, prove that he was a Christian. He was not one of those who act or pray, “that they may be seen of men.” He communed with his God in secret.

My mother resided two years at Mount Vernon after her marriage with John Parke Custis, the only son of Mrs. Washington. I have heard her say that General Washington always received the sacrament with my grandmother before the revolution. When my aunt, Miss Custis died suddenly at Mount Vernon, before they could realize the event, he knelt by her and prayed most fervently, most affectingly, for her recovery. Of this I was assured by Judge Washington’s mother and other witnesses…

…She never omitted her private devotions, or her public duties; and she and her husband were so perfectly united and happy that he must have been a Christian. She had no doubts, no fears for him. After forty years of devoted affection and uninterrupted happiness, she resigned him without a murmur into the arms of his Savior and his God, with the assured hope of his eternal felicity. Is it necessary that any one should certify, “General Washington avowed himself to me a believer in Christianity?” As well may we question his patriotism, his heroic, disinterested devotion to his country. His mottos were, “Deeds, not Words”; and, “For God and my Country.”

(The full text of the letter can be found in The Writings of George Washington, by Jared Sparks, published by American Stationers’ Company, Boston, 1837. Volume 12, page 406, letter of Eleanor Parke Lewis, 26 February, 1833.)

From the foregoing, we see that nothing whatsoever can be inferred from the fact that George Washington did not kneel during religious services, as it was then the custom to stand during the devotional parts of the service. We also see that Washington did kneel in prayer on at least one occasion, even though the account of his kneeling at Valley Forge is mythical.

The piety and Christianity of George Washington

George Washington was, privately, a pious man. Historian Peter Lillback, Ph. D., the president of Westminster Theological Seminary, published a book titled, George Washington’s Sacred Fire (Providence Forum, 2006), in which he summarized the evidence for Washington’s religiosity, using documents that were previously unavailable to historians. Here’s what he wrote in an online article summarizing his findings, titled, Why Have Scholars Underplayed George Washington’s Faith? (February 10, 2007):

It has simply been too easy for all parties in this debate to rely on secondary sources. Ultimately, Washington’s own words and his own actions in his own context establish the truth about his own faith…

Within this vast collection of Washington’s own words and writings, we now have a remarkable ability to uncover what earlier scholars were unable to access. And when we let Washington’s own words and deeds speak for his faith we get quite a different perspective than that of most recent modern historians. Washington referred to himself frequently using the words “ardent”, “fervent”, “pious”, and “devout”. There are over one hundred different prayers composed and written by Washington in his own hand, with his own words, in his writings. He described himself as one of the deepest men of faith of his day when he confessed to a clergyman, “No Man has a more perfect Reliance on the alwise, and powerful dispensations of the Supreme Being than I have nor thinks his aid more necessary.”

Rather than avoid the word “God,” on the very first national Thanksgiving under the U.S. Constitution, he said, “It is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor.” Although he never once used the word “Deist” in his voluminous writings, he often mentioned religion, Christianity, and the Gospel. He spoke of Christ as “the divine Author of our blessed religion.” He encouraged missionaries who were seeking to “Christianize” the “aboriginals.” He took an oath in a private letter, “on my honor and the faith of a Christian.” He wrote of “the blessed religion revealed in the Word of God.” He encouraged seekers to learn “the religion of Jesus Christ.” He even said to his soldiers, “To the distinguished Character of Patriot, it should be our highest Glory to add the more distinguished Character of Christian.” Not bad for a “lukewarm” Episcopalian!

Historians ought no longer be permitted to do the legerdemain of turning Washington into a Deist even if they found it necessary and acceptable to do so in the past. Simply put, it is time to let the words and writings of Washington’s faith speak for themselves.

Seven telling pieces of evidence that George Washington was a Christian

Ever since the publication of a book by Paul F. Boller, Jr. entitled George Washington and Religion (Southern Methodist University Press, 1963), it has become fashionable for scholars to claim that Washington was not a Christian but a Deist. However, Kerby Anderson, president of Probe Ministries International, adduces no less than seven telling pieces of evidence that George Washington was a Christian in his article, George Washington and Religion:

What are some of the reasons to believe Washington was a Christian? First, he religiously observed the Sabbath as a day of rest and frequently attended church services on that day. Second, many report that Washington reserved time for private prayer. Third, Washington saved many of the dozens of sermons sent to him by clergymen, and read some of them aloud to his wife.

Fourth, Washington hung paintings of the Virgin Mary and St. John in places of honor in his dining room in Mount Vernon. Fifth, the chaplains who served under him during the long years of the Revolutionary War believed Washington was a Christian. Sixth, Washington (unlike Thomas Jefferson) was never accused by the press or his opponents of not being a Christian.

It is also worth noting that, unlike Jefferson, Washington agreed to be a godparent for at least eight children. This was far from a casual commitment since it required the godparents to agree to help insure that a child was raised in the Christian faith. Washington not only agreed to be a godparent, but presented his godsons and goddaughters with Bibles and prayer books.

George Washington was not a Deist who believed in a “watchmaker God.” He was a Christian and demonstrated that Christian character throughout his life.

The smoking gun that proves Washington was a Christian, who believed Jesus was God

In a letter from George Washington to the Governors of the States (June 8, 1783), George Washington expressed his desire that the governors and the citizens of the states over which they preside would seek to acquire the attributes and characteristics of Jesus Christ, “the Divine Author of our blessed religion.” I shall quote from the final three paragraphs:

It remains, then, to be my final and only request, that your Excellency will communicate these sentiments to your legislature at their next meeting, and that they may be considered as the legacy of one, who has ardently wished, on all occasions, to be useful to his country, and who, even in the shade of retirement, will not fail to implore the Divine benediction upon it.

I now make it my earnest prayer that God would have you, and the State over which you preside, in his holy protection; that he would incline the hearts of the citizens to cultivate a spirit of subordination and obedience to government; to entertain a brotherly affection and love for one another, for their fellow citizens of the United States at large, and particularly for their brethren who have served in the field; and finally, that he would most graciously be pleased to dispose us all to do justice, to love mercy, and to demean ourselves with that charity, humility, and pacific temper of mind, which were the characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed religion, and without an humble imitation of whose example in these things, we can never hope to be a happy nation.

I have the honor to be, with much esteem and respect, Sir, your Excellency’s most obedient and most humble servant.

George Washington

Since Washington lists humility as one of the characteristics of “the Divine Author of our blessed religion,” he cannot simply be referring to the God worshiped by the Deists. The only kind of God Who could be said to possess “humility” is One Who humbled Himself to be born as a human being. The above passage thus shows that Washington acknowledged the Divinity of Christ: he was a Trinitarian Christian.

Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamation

Far from being a rigid absolutist regarding the separation of Church and State, President George Washington actually instituted a national day of prayer, in his Thanksgiving Proclamation of October 3, 1789 – an event which the Freedom From Religion Foundation omits to mention in its advertisement:

[New York, 3 October 1789]

By the President of the United States of America. a Proclamation.

Whereas it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor — and whereas both Houses of Congress have by their joint Committee requested me “to recommend to the People of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.”

Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be — That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks — for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation–for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his Providence which we experienced in the tranquillity, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed — for the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted — for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed; and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge; and in general for all the great and various favors which he hath been pleased to confer upon us.

and also that we may then unite in most humbly offering our prayers and supplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations and beseech him to pardon our national and other transgressions — to enable us all, whether in public or private stations, to perform our several and relative duties properly and punctually — to render our national government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed — to protect and guide all Sovereigns and Nations (especially such as have shewn kindness onto us) and to bless them with good government, peace, and concord — To promote the knowledge and practice of true religion and virtue, and the encrease of science among them and us –and generally to grant unto all Mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as he alone knows to be best.

Given under my hand at the City of New-York the third day of October in the year of our Lord 1789.

Washington considered religion politically indispensable

In his Farewell Address of 1796, President George Washington made it clear that he not only regarded religion as indispensable to a well-governed society, but that he also believed that public morality could not be maintained without religion:

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism, who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connections with private and public felicity. Let it simply be asked: Where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice ? And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

Why, I wonder, does the Freedom From Religion Foundation consider a man who professed his faith in the Divinity of Christ, who regarded atheists as stupid, who declared in his farewell address that no-one who sought to undermine religion could be regarded as a patriot, who was skeptical that public morality could survive without religion, and who instituted the national day of prayer that Americans know as Thanksgiving, as a political ally of theirs? Beats me.

4. John Adams, second President of the United States

|

The Freedom From Religion Foundation quote from President John Adams reads as follows:

“The government of the United States is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion.”

– Signed Treaty of Tripoli, 1797

The FFRF advertisement goes on to claim (incorrectly, as we’ll see below) that Adams “did not believe in miracles or prophecies.”

The quote is substantially accurate. Here’s the relevant passage from Article XI of the Treaty:

As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion – as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen, – and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries. (Charles I. Bevans, ed. Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America 1776-1949. Vol. 11: Philippines-United Arab Republic. Washington D.C.: Department of State Publications, 1974, p. 1072).

John Adams regarded God as the ultimate foundation of human rights

In his 1765 work, A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law, Adams insisted that human rights are God-given and cannot be repealed by human laws. The people, for Adams, have “an indisputable, unalienable, indefeasible, divine right” to know what their rulers are getting up to:

The poor people, it is true, have been much less successful than the great. They have seldom found either leisure or opportunity to form a union and exert their strength; ignorant as they were of arts and letters, they have seldom been able to frame and support a regular opposition. This, however, has been known by the great to be the temper of mankind; and they have accordingly labored, in all ages, to wrest from the populace, as they are contemptuously called, the knowledge of their rights and wrongs, and the power to assert the former or redress the latter. I say RIGHTS, for such they have, undoubtedly, antecedent to all earthly government, — Rights, that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws — Rights, derived from the great Legislator of the universe.…

Liberty cannot be preserved without a general knowledge among the people, who have a right, from the frame of their nature, to knowledge, as their great Creator, who does nothing in vain, has given them understandings, and a desire to know; but besides this, they have a right, an indisputable, unalienable, indefeasible, divine right to that most dreaded and envied kind of knowledge, I mean, of the characters and conduct of their rulers. Rulers are no more than attorneys, agents, and trustees, of the people; and if the cause, the interest, and trust, is insidiously betrayed, or wantonly trifled away, the people have a right to revoke the authority that they themselves have deputed, and to constitute other and better agents, attorneys and trustees.

Adams believed that American independence was built upon the foundations of Christianity

An excerpt from one of John Adams’ private letters to Thomas Jefferson makes it abundantly clear that he believed American independence was built upon the foundations of Christianity, when he points out that this was the one thing that united all of the soldiers fighting for independence:

Who composed that Army of fine young Fellows that was then before my Eyes? There were among them, Roman Catholicks, English Episcopalians, Scotch and American Presbyterians, Methodists, Moravians, Anababtists, German Lutherans, German Calvinists Universalists, Arians, Priestleyans, Socinians, Independents, Congregationalists, Horse Protestants and House Protestants, Deists and Atheists; and “Protestans qui ne croyent rien [“Protestants who believe nothing”].” Very few however of several of these Species. Nevertheless all Educated in the general Principles of Christianity: and the general Principles of English and American Liberty…

The general Principles, on which the Fathers Atchieved Independence, were the only Principles in which that beautiful Assembly of young Gentlemen could Unite, and these Principles only could be intended by them in their Address, or by me in my Answer. And what were these general Principles? I answer, the general Principles of Christianity, in which all those Sects were united: And the general Principles of English and American Liberty, in which all those young Men United, and which had United all Parties in America, in Majorities sufficient to assert and maintain her Independence.

Now I will avow, that I then believed, and now believe, that those general Principles of Christianity, are as eternal and immutable, as the Existence and Attributes of God; and that those Principles of Liberty, are as unalterable as human Nature and our terrestrial, mundane System. I could therefore safely say, consistently with all my then and present Information, that I believed they would never make Discoveries in contradiction to these general Principles. In favour of these general Principles in Phylosophy, Religion and Government, I could fill Sheets of quotations from Frederick of Prussia, from Hume, Gibbon, Bolingbroke, Reausseau and Voltaire, as well as Neuton and Locke: not to mention thousands of Divines and Philosophers of inferiour Fame.

(Source: John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, June 28th, 1813, from Quincy. The Adams-Jefferson Letters: The Complete Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and Abigail and John Adams, edited by Lester J. Cappon, 1988, the University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, pp. 338-340.)

John Adams was a Christian who believed in miracles, not a Deist

John Adams was no Deist. In 1796, John Adams denounced Thomas Paine’s criticisms of Christianity in his Deist work, The Age of Reason, saying, “The Christian religion is, above all the religions that ever prevailed or existed in ancient or modern times, the religion of wisdom, virtue, equity and humanity, let the Blackguard Paine say what he will.” (The Works of John Adams (1854), vol III, p 421, diary entry for July 26, 1796.)

American history researcher Gregg L. Frazer (2004) notes that, while Adams shared many perspectives with deists, “Adams clearly was not a deist. Deism rejected any and all supernatural activity and intervention by God; consequently, deists did not believe in miracles or God’s providence…. Adams, however, did believe in miracles, providence, and, to a certain extent, the Bible as revelation.” (The Political Theology of the American Founding (PhD dissertation), Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, California, 2004, p. 46.)

UPDATE: It has come to my attention that some people have questioned the accuracy of Dr. Frazer’s work. In order to remove all doubt that John Adams believed in miracles, here’s his diary entry for March 2, 1756:

Began this afternoon my third quarter. The great and Almighty author of nature, who at first established those rules which regulate the world, can as easily suspend those laws whenever his providence sees sufficient reason for such suspension. This can be no objection, then, to the miracles of Jesus Christ. Although some very thoughtful and contemplative men among the heathen attained a strong persuasion of the great principles of religion, yet the far greater number, having little time for speculation, gradually sunk into the grossest opinions and the grossest practices. These, therefore, could not be made to embrace the true religion till their attention was roused by some astonishing and miraculous appearances. The reasoning of philosophers, having nothing surprising in them, could not overcome the force of prejudice, custom, passion, and bigotry. But when wise and virtuous men commissioned from heaven, by miracles awakened men’s attention to their reasonings, the force of truth made its way with ease to their minds.

Quotations adduced by atheists which purport to show that President John Adams was skeptical of miracles, show nothing of the sort. What they show is that John Adams rejected the miracles claimed by the Catholic Church, which he regarded as fraudulent: they were the “fictitious miracles” of “priests and kings.”

(End of Update.)

The Website www.adherents.com has an informative article titled, The Religious Affiliation of Second U.S. President John Adams, which states, among other things:

President John Adams was a devout Unitarian, which was a non-trinitarian Protestant Christian denomination during the Colonial era…

Adams was raised a Congregationalist, but ultimately rejected many fundamental doctrines of conventional Christianity, such as the Trinity and the divinity of Jesus, becoming a Unitarian. In his youth, Adams’ father urged him to become a minister, but Adams refused, considering the practice of law to be a more noble calling. Although he once referred to himself as a “church going animal,” Adams’ view of religion overall was rather ambivalent: He recognized the abuses, large and small, that religious belief lends itself to, but he also believed that religion could be a force for good in individual lives and in society at large. His extensive reading (especially in the classics), led him to believe that this view applied not only to Christianity, but to all religions.

Adams was aware of (and wary of) the risks, such as persecution of minorities and the temptation to wage holy wars, that an established religion poses. Nonetheless, he believed that religion, by uniting and morally guiding the people, had a role in public life.

President Adams’ proclamation of a national day of prayer and fasting

On March 23, 1798, President John Adams also publicly proclaimed that May 9, 1798 should be designated a national Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer. Here is an extract from the proclamation:

As the safety and prosperity of nations ultimately and essentially depend on the protection and the blessing of Almighty God, and the national acknowledgment of this truth is not only an indispensable duty which the people owe to Him, but a duty whose natural influence is favorable to the promotion of that morality and piety without which social happiness cannot exist nor the blessings of a free government be enjoyed; and as this duty, at all times incumbent, is so especially in seasons of difficulty or of danger, when existing or threatening calamities, the just judgments of God against prevalent iniquity, are a loud call to repentance and reformation; and as the United States of America are at present placed in a hazardous and afflictive situation by the unfriendly disposition, conduct, and demands of a foreign power, evinced by repeated refusals to receive our messengers of reconciliation and peace, by depredation on our commerce, and the infliction of injuries on very many of our fellow-citizens while engaged in their lawful business on the seas–under these considerations it has appeared to me that the duty of imploring the mercy and benediction of Heaven on our country demands at this time a special attention from its inhabitants.

I have therefore thought fit to recommend, and I do hereby recommend, that Wednesday, the 9th day of May next, be observed throughout the United States as a day of solemn humiliation, fasting, and prayer; that the citizens of these States, abstaining on that day from their customary worldly occupations, offer their devout addresses to the Father of Mercies agreeably to those forms or methods which they have severally adopted as the most suitable and becoming; that all religious congregations do, with the deepest humility, acknowledge before God the manifold sins and transgressions with which we are justly chargeable as individuals and as a nation, beseeching Him at the same time, of His infinite grace, through the Redeemer of the World, freely to remit all our offenses, and to incline us by His Holy Spirit to that sincere repentance and reformation which may afford us reason to hope for his inestimable favor and heavenly benediction; that it be made the subject of particular and earnest supplication that our country may be protected from all the dangers which threaten it…

Misquotation of President John Adams by Richard Dawkins: An example of how secular humanists misappropriate the Founding Fathers

The Chistian apologist Richard Deem, over at his Website, Evidence for God from Science: Christian Apologetics, has a review of Professor Richard Dawkins’ best-selling book, The God Delusion. In his review of the second chapter, entitled, Debunking Dawkins: The God Delusion – Chapter 2: The God Hypothesis, Deem shows how Dawkins completely mis-represents President John Adams, as someone who was opposed to religion:

Dawkins goes on to quote several founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin, who made statement against the religion of their time. John Adams is quoted as saying, “This would be the best of all possible worlds, if there were no religion in it.” However here is the complete quote in an April 19, 1817, letter to Thomas Jefferson:

“Twenty times in the course of my late reading have I been on the point of breaking out, ‘This would be the best of all possible worlds, if there were no religion at all!!!’ But in this exclamation I would have been as fanatical as Bryant or Cleverly. Without religion, this world would be something not fit to be mentioned in polite company, I mean hell.” (Letter to Thomas Jefferson, April 19, 1817.)

In quoting John Adams out-of-context, Dawkins has made it seem that Adams said exactly opposite of what he really intended. No wonder he left out the part where Adams said the world would be “hell” “without religion.” Adams directly refuted Dawkins’ major premise of the book – that religion is the great evil in the world – and affirmed the opposite – that religion keeps the world from becoming completely evil. In fact, John Adams said some things about Christianity that Dawkins probably won’t be quoting any time soon such as, “The Christian religion, in its primitive purity and simplicity, I have entertained for more than sixty years. It is the religion of reason, equity, and love; it is the religion of the head and the heart.” (Letter to F.A. Van Der Kemp, December 27, 1816.)

5. Thomas Jefferson, third President of the United States

|

The Freedom From Religion Foundation quote from President Thomas Jefferson reads as follows:

“Question with boldness even the existence of a God; because, if there be one, he must more approve of the homage of reason, than that of blindfolded fear.”

Jefferson encouraged bold and fearless inquiry into the claims of religion

President Jefferson did indeed say that, in a 1787 letter to his nephew, Peter Carr. In the same letter, he went on to write:

Do not be frightened from this inquiry by any fear of its consequences. If it ends in a belief that there is no God, you will find incitements to virtue in the comfort and pleasantness you feel in its exercise, and the love of others which it will procure you. If you find reason to believe there is a God, a consciousness that you are acting under his eye, and that he approves you, will be a vast additional incitement; if that there be a future state, the hope of a happy existence in that increases the appetite to deserve it; if that Jesus was also a God, you will be comforted by a belief of his aid and love. In fine, I repeat, you must lay aside all prejudice on both sides, and neither believe nor reject anything, because any other persons, or description of persons, have rejected or believed it. Your own reason is the only oracle given you by heaven, and you are answerable, not for the rightness, but uprightness of the decision.

In the foregoing passage, Jefferson maintained that an atheist could still live virtuously, but also freely acknowledged that belief in a just God and an afterlife were additional incitements to virtue.

Jefferson held that a free society is founded on a popular belief in God-given liberties

In his 1785 Notes on the State of Virginia, when discussing the moral corruption caused by the institution of slavery, Jefferson maintained that no nation could remain secure in its liberties without “a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God,” which implies that he would have regarded a nation of atheists as politically non-viable, in the long term:

“The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other… And with what execration should the statesman be loaded, who permitting one half the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the other, transforms those into despots, and these into enemies, destroys the morals of the one part, and the amor patriae [love of country – VJT] of the other… Can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever; that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events; that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest.” (Query 18.

Thomas Jefferson, Intelligent Design advocate

President Jefferson also argued on rational grounds that the universe and its numerous life-forms could only be the product of an Intelligent Agent, in his letter to John Adams, from Monticello, dated April 11, 1823:

I hold (without appeal to revelation) that when we take a view of the Universe, in its parts general or particular, it is impossible for the human mind not to perceive and feel a conviction of design, consummate skill, and indefinite power in every atom of its composition. The movements of the heavenly bodies, so exactly held in their course by the balance of centrifugal and centripetal forces, the structure of our earth itself, with its distribution of lands, waters and atmosphere, animal and vegetable bodies, examined in all their minutest particles, insects mere atoms of life, yet as perfectly organized as man or mammoth, the mineral substances, their generation and uses, it is impossible, I say, for the human mind not to believe that there is, in all this, design, cause and effect, up to an ultimate cause, a fabricator of all things from matter and motion, their preserver and regulator while permitted to exist in their present forms, and their regenerator into new and other forms.

We see, too, evident proofs of the necessity of a superintending power to maintain the Universe in its course and order. Stars, well known, have disappeared, new ones have come into view, comets, in their incalculable courses, may run foul of suns and planets and require renovation under other laws; certain races of animals are become extinct; and, were there no restoring power, all existences might extinguish successively, one by one, until all should be reduced to a shapeless chaos. So irresistible are these evidences of an intelligent and powerful Agent that, of the infinite numbers of men who have existed thro’ all time, they have believed, in the proportion of a million at least to Unit, in the hypothesis of an eternal pre-existence of a creator, rather than in that of a self-existent Universe. Surely this unanimous sentiment renders this more probable than that of the few in the other hypothesis. Some early Christians indeed have believed in the coeternal pre-existence of both the Creator and the world, without changing their relation of cause and effect.

Once again, I have to ask the Freedom From Religion Foundation why it considers a President who held that the existence of God could be rationally proved, and that no society could long remain free unless its people believed that their liberties derived from God, as a political ally.

6. James Madison, fourth President of the United States

|

The Freedom From Religion Foundation quote reads as follows:

During almost fifteen centuries has the legal establishment of Christianity been on trial. What have been its fruits? More or less in all places, pride and indolence in the Clergy, ignorance and servility in the laity, in both, superstition, bigotry and persecution.

The quote is taken from the seventh numbered paragraph of Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments of 1785, which was addressed to “the Honorable the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia.”

The attentive reader will note that Madison is not criticizing Christianity in the above passage; rather, what he is attacking is “the legal establishment of Christianity” – which is quite a different thing.

The Freedom From Religion Foundation shoots itself in the foot

I find it particularly ironic that in the very same document quoted by the Freedom From Religion Foundation in an attempt to support that Christianity leads to superstition and bigotry, James Madison clearly stated that his opposition to the proposed Virginia “Bill establishing a provision for Teachers of the Christian Religion” was based largely on his belief that the Bill would harm Christianity:

“The policy of the bill is adverse to the diffusion of the light of Christianity. The first wish of those who enjoy this precious gift ought to be, that it may be imparted to the whole race of mankind. Compare the number of those who have as yet received it, with the number still remaining under the dominion of false religions, and how small is the former! Does the policy of the bill tend to lessen the disproportion? No: it at once discourages those who are strangers to the light of Revelation from coming into the region of it: countenances, by example, the nations who continue in darkness, in shutting out those who might convey it to them.”

[Madison, James, A Memorial and Remonstrance on the Religious Rights of Man, S. C. Ustick, Washington, 1828, p. 10]

President Madison believed that religion was essential for public morality

Unlike Thomas Jefferson, who believed that people could still remain moral even if they no longer believed in God, James Madison held that religion was essential for public morality:

“The belief in a God All Powerful wise and good, is so essential to the moral order of the world and to the happiness of man, that arguments which enforce it cannot be drawn from too many sources nor adapted with too much solicitude to the different characters and capacities to be impressed with it.”

– Letter to Rev. Frederick Beasley (November 20, 1825)

James Madison held that the existence of God could be known by reason alone

As a young man, James Madison had read the writings of the English philosopher and theologian Dr. Samuel Clarke, whose 1704 work, A Discourse Concerning the Being and Attributes of God, attempted to demonstrate the existence of God in a rigorous logical fashion. In a letter to a Dr. C. Caldwell, written in November 1825, Madison thanked Dr. Caldwell for a philosophical memoir which dealt with, among other topics, the proofs of the Being and attributes of God. Madison then expressed his puzzlement at the existence of some clergymen who rejected the possibility of arguing from Nature to a Divine Creator and who held that oral tradition (which pre-dated the Bible) was the only reliable road to God. Such a view, argued Madison, was not only extraordinary, but also un-Biblical (doubtless he was thinking of passages such as Romans 1:20):

“I concur with you at once in rejecting the idea maintained by some divines, of more zeal than discretion, that there is no road from nature up to nature’s God, and that all the knowledge of his existence and attributes which preceded the written revelation of them was derived from oral tradition. The doctrine is the more extraordinary, as it so directly contradicts the declarations you have cited from the written authority itself.” (Madison, James, Letters and Other Writings of James Madison, vol. 3, J. B. Lippincott &Co., 1865, p. 505)

In a letter to Rev. Frederick Beasley dated November 20, 1825, Madison expressed his appreciation of a tract which Rev. Beasley had sent him, on the Being and attributes of God. Madison then went on to give his own opinion the argument to a First Cause would be the most efficacious in persuading people of God’s existence:

But whatever effect may be produced on some minds by the more abstract train of ideas which you so strongly support, it will probably always be found that the course of reasoning from the effect to the cause, “from Nature to Nature’s God,” Will be the more universal & more persuasive application.

(Madison, James, Letters and Other Writings of James Madison, vol. 3, J. B. Lippincott &Co., 1865, p. 504)

I conclude that Madison’s religious views have been mis-represented by the Freedom From Religion Foundation.

Is the American Constitution godless?

|

As we saw above, the Freedom From Religion Foundation described the American Constitution as “godless” in its July 4 advertisement. Now, it is certainly true that the Constitution doesn’t explicitly mention God. But I’d like to point out that James Cardinal Gibbons (1834-1921, pictured above, 1914) didn’t think it was necessary or desirable for the Constitution to include a mention of God. As he put it in his Address, “The Religious Element in American Civilization” (h/t captainjamesdavis.net):

At first sight it might seem that religious principles were entirely ignored by the fathers of the Republic in framing the Constitution, as it contains no reference to God, and makes no appeal to religion. And so strongly have certain religious sects been impressed with this fact that they have tried to get the name of God incorporated into that document. But the omission of God’s holy name affords no just criterion of the religious character of the founders of the Republic, or of the Constitution which they framed. Nor should we have any concern to have the name of God imprinted in the Constitution, so long as the Instrument itself is interpreted by the light of Christian revelation. I would rather sail under the guidance of a living captain than of a figure-head at the prow of the ship. Far better for the nation that His Spirit should animate our laws, that He should be invoked in our Courts of Justice, that He should be worshipped in our Sabbaths and thanksgivings, and that His guidance should be implored in the opening of our Congressional proceedings.

But as Cardinal Gibbons went on to observe, the American Declaration of Independence is another matter: it is replete with references to God, from start to finish:

God’s holy name greets us in the opening paragraph, and is piously invoked in the last sentence of the Declaration; and thus it is, at the same time, the corner-stone and the keystone of this great monument to freedom. The illustrious signers declared that “when, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands that have connected them with another, and to, assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect for the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to the separation.” They acknowledge one Creator, the source of “life, liberty, and of happiness.” They “appeal to the Supreme judge of the world” for the rectitude of their intentions, and they conclude in this solemn language: “For the support of this declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”

Cardinal Gibbons went on to argue that the laws of the United States are intimately inter-woven with the Christian religion:

The laws of the United States are so intimately interwoven with the Christian religion that they cannot be adequately expounded without the light of revelation. “The common law,” says Kent, “is the common jurisprudence of the United States, and was brought from England and established here, so far as it was adapted to our institutions and circumstances. It is an incontrovertible fact that the common law of England is, to a great extent, founded on the principles of Christian ethics. The maxims of the Holy Scriptures form the great criterion of right and wrong in the civil courts…

Note. — The oath of the President of the United States before he assumes the duties of office; that administered in courts of justice, not only to witnesses, but also to the judge, jury, lawyers, and officers of the court, in accordance with the Constitution, — implies a belief in God and forms of acts of worship. It is a national tribute to the universal sovereignty of the Creator. By the act of taking an oath a man makes a profession of faith in God’s unfailing truth, absolute knowledge, and infinite sanctity. The Christian Sabbath is revered, as a day of rest and public prayer, throughout the laud. This is national homage to the Christian religion.

The U. S. Constitution – not quite “godless”?

I was intrigued by Cardinal Gibbons’ reference to the Christian Sabbath, and did a little more research. I found that to this day, it is still acknowledged in the U.S. Constitution. Here it is, tucked away in Article 1, Section 7, part of which reads as follows:

If any Bill shall not be returned by the President within ten Days (Sundays excepted) after it shall have been presented to him, the Same shall be a Law, in like Manner as if he had signed it, unless the Congress by their Adjournment prevent its Return, in which Case it shall not be a Law.

The Freedom From Religion Foundation would have us believe that America is not, in any sense, a Christian nation. But the Supreme Court took a different view in a case entitled, Church of the Holy Trinity vs. the United States, 143 U. S. 457

This is a religious people. This is historically true. From the discovery of this continent to the present hour, there is a single voice making this affirmation. The commission to Christopher Columbus … [recited] that “it is hoped that by God’s assistance some of the continents and islands in the ocean will be discovered . . . .” The first colonial grant made to Sir Waiter Raleigh in 1584… and the grant authorizing him to enact statutes for the government of the proposed colony provided that “they be not against the true Christian faith . . . .” The first charter of Virginia, granted by King James I in 1606 . . . commenced the grant in these words: ” . . . in propagating of Christian Religion to such People as yet live in Darkness . . . . Language of similar import may be found in the subsequent charters of that colony . . . in 1609 and 1611; and the same is true of the various charters granted to the other colonies. In language more or less emphatic is the establishment of the Christian religion declared to be one of the purposes of the grant. The celebrated compact made by the Pilgrims in the Mayflower, 1620, recites: “Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith . . . a voyage to plant the first colony in the northern parts of Virginia . . . . The fundamental orders of Connecticut, under which a provisional government was instituted in 1638-1639, commence with this declaration: ” … And well knowing where a people are gathered together the word of God requires that to maintain the peace and union . . . there should be an orderly and decent government established according to God . . . to maintain and preserve the liberty and purity of the gospel of our Lord Jesus which we now profess . . . of the said gospel [which] is now practiced amongst us.” In the charter of privileges granted by William Penn to the province of Pennsylvania, in 1701, it is recited: ” … no people can be truly happy, though under the greatest enjoyment of civil liberties, if abridged of. . . their religious profession and worship . . . . Coming nearer to the present time, the Declaration of Independence recognizes the presence of the Divine in human affairs in these words: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights . . . appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions . . . “; “And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the Protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.”…

The Court ruling went on to describe America as a “Christian nation”:

If we pass beyond these matters to a view of American life, as expressed by its laws, its business, its customs, and its society, we find every where a clear recognition of the same truth. Among other matters, note the following: the form of oath universally prevailing, concluding with an appeal to the Almighty; the custom of opening sessions of all deliberative bodies and most conventions with prayer; the prefatory words of all wills, “In the name of God, amen;” the laws respecting the observance of the Sabbath, with the general cessation of all secular business, and the closing of courts, legislatures, and other similar public assemblies on that day; the churches and church organizations which abound in every city, town, and hamlet; the multitude of charitable organizations existing every where under Christian auspices; the gigantic missionary associations, with general support, and aiming to establish Christian missions in every quarter of the globe. These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterances that this is a Christian nation.

Readers might also be interested in the online article, A Godless Constitution?: A Response to Kramnick and Moore by Daniel L. Dreisbach.

In conclusion: the claim that the Founding Fathers were out-and-out secularists, in anything like the modern sense of the word, does not withstand scrutiny. They were God-fearing men who believed that religion played an essential part in public morality. Nor was the Constitution they composed a “godless” document, as the Freedom From Religion Foundation claimed. Rather, it needs to be understood in its historical context. Situated in that context, it can be readily perceived that the Constitution is anything but godless.