In previous articles, I have argued that even if our universe is part of some larger multiverse, we still have excellent scientific grounds for believing that our universe – and also the multiverse in which it is embedded – is fine-tuned to permit the possibility of life. Moreover, the only adequate explanation for the extraordinary degree of fine-tuning we observe in the cosmos is that it is the product of an Intelligence. That is the cosmological fine-tuning argument, in a nutshell. My articles can be viewed here:

So you think the multiverse refutes cosmological fine-tuning? Consider Arthur Rubinstein

Beauty and the multiverse

Why a multiverse would still need to be fine-tuned, in order to make baby universes

Scientific challenges to the cosmological fine-tuning argument can be ably rebutted, as this article by Dr. Robin Collins shows. However, there are three objections to fine-tuning which I keep hearing from atheists over and over again. Here they are:

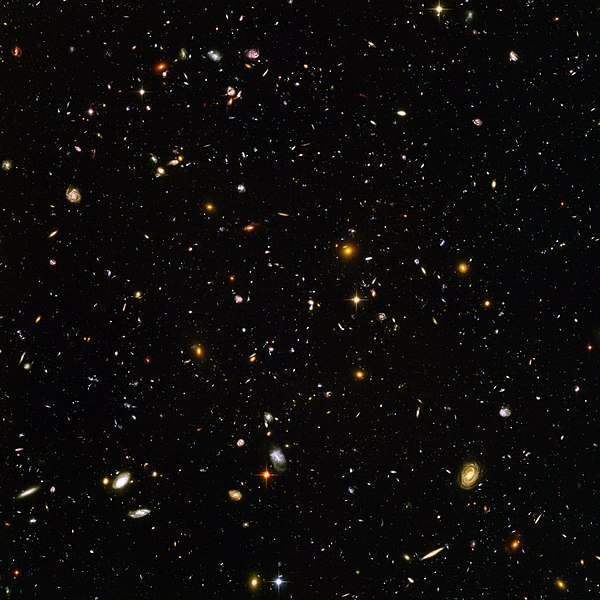

1. If the universe was designed to support life, then why does it have to be so BIG, and why is it nearly everywhere hostile to life? Why are there so many stars, and why are so few orbited by life-bearing planets?

2. If the universe was designed to support life, then why does it have to be so OLD, and why was it devoid of life throughout most of its history? For instance, why did life on Earth only appear after 70% of the cosmos’s 13.7-billion-year history had already elapsed? And Why did human beings (genus Homo) only appear after 99.98% of the cosmos’s 13.7-billion-year history had already elapsed?

3. If the universe was designed to support life, then why does Nature have to be so CRUEL? Why did so many animals have to die – and why did so many species of animals have to go extinct (99% is the commonly quoted figure), in order to generate the world as we see it today? What a waste! And what about predation, parasitism, and animals that engage in practices such as serial murder and infant cannibalism?

In today’s post, I’m not going to attempt to provide any positive reasons why we should expect an intelligently designed universe to be big and old, and why we should not be too surprised if it contains a lot of suffering. I’ll talk about those reasons in my next post. What I’m going to do in this post is try to clear the air, and explain why I regard the foregoing objections to the cosmic fine-tuning argument as weak and inconclusive.

Here are seven points I’d like atheists who object to the cosmological fine-tuning argument to consider:

1. If you don’t like the universe that we live in, then the onus is on you to show that a better universe is physically possible, given a different set of laws and/or a different fundamental theory of physics. Only when you have done this are you entitled to make the argument that our universe is so poorly designed that no Intelligent Being could possibly have made it.

At this point, I expect to hear splutterings of protest: “But that’s not our problem. It’s God’s. Isn’t your God omnipotent? Can’t He make anything He likes – including a perfect universe?” Here’s my answer: “First, the cosmological fine-tuning argument claims to establish the existence of an Intelligent Designer, who may or may not be omnipotent. Second, even an omnipotent Being can only make things that can be coherently described. So what I want you to do is provide me with a physical model of your better universe, showing how its laws and fundamental theory of physics differ from those of our universe, and why these differences make it better. Until you can do that, you’d better get back to work.”

2. Imaginability doesn’t imply physical possibility. I can imagine a winged horse, but that doesn’t make it physically possible. The question still needs to be asked: “How would it fly?” I can also imagine a nicer universe where unpleasant things never happen, but I still have to ask myself: “What kind of scientific laws and what kind of fundamental theory would need to hold in that nicer universe, in order to prevent unpleasant things from happening?”

3. As Dr. Robin Collins has argued, the laws of our universe are extremely elegant, from a mathematical perspective. (See also my post, Beauty and the multiverse.) If there is an Intelligent Designer, He presumably favors mathematical elegance. However, even if a “nicer” universe proved to be physically possible, in a cosmos characterized by some other set of scientific laws and a different fundamental theory of physics, the scientific laws and fundamental theory of such a universe might not be anywhere near as mathematically elegant as those of the universe that we live in. The Intelligent Designer might not want to make a “nice”, pain-free universe, if doing so entails making a messy, inelegant universe.

4. If a Designer wanted to design a universe that was free from animal suffering (i.e. a world in which animals were able to avoid noxious stimuli, without the conscious feeling of pain), there are two ways in which He could accomplish this: He could either use basic, macro-level laws of Nature (e.g. “It is a law of Nature that no animal that is trapped in a forest fire shall suffer pain”) or micro-level laws (i.e. by making laws of Nature precluding those physical arrangements of matter in animals’ brain and nervous systems which correspond to pain).

The first option is incompatible with materialism. If you believe in the materialist doctrine of supervenience (that any differences between two animals’ mental states necessarily reflect an underlying physical difference between them), it automatically follows that if a trapped animal’s brain and nervous system instantiates a physical arrangement of matter which corresponds to pain, then that animal will suffer pain, period. No irreducible, top-down “macro-level” law can prevent that, in a materialistic universe. So if you’re asking the Designer to make a world where unpleasant or painful things never happen by simply decreeing this, then what you’re really asking for is a world in which animals’ minds cannot be described in materialistic terms. Are you sure you want that?

The second option is unwieldly. There are a vast number of possible physical arrangements of matter in animals’ brain and nervous systems which correspond to pain, and there is no single feature that they all possess in common, at the micro level. An Intelligent Designer would need to make a huge number of extra laws, in order to preclude each and every one of these physical arrangements. That in turn would make the laws of Nature a lot less elegant, when taken as a whole. The Intelligent Designer might not want to make such an aesthetically ugly universe.

Eliminating animal suffering might not be a wise thing to do, in any case. One could argue that the conscious experience of pain is, at least sometimes, biologically beneficial, since it subsequently leads to survival-promoting behavior: “Once bitten, twice shy.” (An automatic, unconscious response to noxious stimuli might achieve the same result, but perhaps not as effectively or reliably as conscious pain.) However, if the Designer is going to allow survival-promoting pain into His world, then He will have to allow the neural states corresponding to that pain. If He still wants to rule out pain that doesn’t promote survival, then He’s going to have to make funny, top-down “macro-level” laws to ensure this – for instance: “It is a law of nature that neural state X [which correspinds to pain in one’s right toe] is only allowed to exist if it benefits the animal biologically.” Note the reference to the whole animal here. You’re asking Mother Nature to check whether the pain would be biologically beneficial to the animal as a whole, before “deciding” whether to allow the animal to experience the feeling of pain or not. But that’s a “macro-level” law, and hence not the kind of law which any card-carrying materialist could consistently ask a Designer to implement.

5. Objections to fine-tuning are of no avail unless they are even more powerful than arguments for fine-tuning. I’d like to use a simple mathematical example to illustrate the point. (I’ve deliberately tried to keep this illustration as jargon-free – and Bayes-free- as possible, so that everyone can understand it.) Suppose, for argument’s sake, that the cosmic fine-tuning argument makes it 99.999999999999999999999 per cent likely (given our current knowledge of physics) that the universe had a Designer. Now suppose, on the other hand, that the vast size and extreme age of the universe, combined with the enormous wastage of animal life and the huge amount of suffering that has occurred during the Earth’s history, make it 99.999999 per cent likely (given our current scientific knowledge of what’s physically possible and what’s not) that a universe containing these features didn’t have a Designer. Given these figures, it would still be rational to accept the cosmic fine-tuning argument, and to believe that our universe had a Designer. Put simply: if someone offers me a 99.999999999999999999999 per cent airtight argument that there is an Intelligent Designer of Nature, and then someone else puts forward a 99.999999 per cent airtight argument that there isn’t an Intelligent Designer, I’m going to go with the first argument and distrust the second. Any sensible person would. Why? Because the likelihood that the first argument is wrong is orders of magnitude lower than the likelihood that the second argument is wrong. Putting it another way: the second argument is “leakier” than the first, so we shouldn’t trust it, if it appears to contradict the first.

6. For the umpteenth time, Intelligent Design theory says nothing about the moral character of the Designer. Even if an atheist could demonstrate beyond all doubt that no loving, personal Designer could have produced the kind of universe we live in, would that prove that there was no Designer? No. All it would show is that the Designer was unloving and/or impersonal – in which case, the logical thing to do (given the strength of the fine-tuning argument) would be to become a Deist. Of course, you might not like such an impersonal Deity – and naturally, it wouldn’t like you, either. But as a matter of scientific honesty, you would be bound to to acknowledge its existence, if that’s where the evidence led.

I’m genuinely curious as to why so few Intelligent Design critics have addressed the philosophy of Deism, and I can only put it down to pique. It’s as if the critics are saying, “Well, I don’t want anything to do with that kind of Deity, as it’s indifferent to suffering. Therefore, I refuse to even consider the possibility that it might exist.” When one puts it like that, it does seem a rather silly attitude to entertain, doesn’t it?

7. From time to time, I have noticed that some atheist critics of the cosmological fine-tuning argument make their case by attacking the God of the Bible. I have often wondered why they focus their attack on such a narrow target, as people of many different religions (and none) can still believe in some sort of God. I strongly suspect that the underlying logic is as follows:

(i) if the cosmological fine-tuning argument is true then there is a Transcendent Designer;

(ii) if there is a Transcendent Designer then it’s possible that this Designer is the God of the Bible;

(iii) but it is impossible that the God of the Bible could exist, because He is a “moral monster”;

(iv) hence, the cosmological fine-tuning argument is not true.

This is a pathological form of reasoning, since it is emotionally driven by a visceral dislike of the God of the Bible. Nevertheless, I believe this form of reasoning is quite common among atheists.

What’s wrong with the foregoing argument? (I shall assume for the purposes of the discussion below that step (i) is true.) At a cursory glance, the argument looks valid:

if A is true then B is true; if B is true then it is possible that C; but it is not possible that C; hence A is not true.

The argument is invalid, however, because it confuses epistemic possibility with real (ontological) possibility. If something is epistemically possible, then for all we know, it might be true. But if something is ontologically possible, then it could really happen. The two kinds of possibility are not the same, because we don’t always know enough to be sure about what could really happen.

Step (ii) of the foregoing argument relates to epistemic possibility, not ontological possibility. It does not say that there is a real possibility that the God of the Bible might exist; it simply says that for all we know, the Transcendent Designer might turn out to be the God the Bible.

Step (iii) of the argument, on the other hand, relates to ontological possibility. It amounts to the claim that since the God the Bible is morally absurd, in His dealings with human beings, no such Being could possibly exist, in reality.

Now, I’m not going to bother discussing the truth or falsity of step (iii) in the foregoing argument. All I intend to say in this post is that even if you believe it to be true, the argument above is an invalid, because the two kinds of possibility in steps (ii) and (iii) are not the same.

Indeed, if you were absolutely sure that step (iii) were true, then you would have to deny step (ii). In which case, the argument fails once again.

In short: attacking the cosmological fine-tuning argument by ridiculing the God of the Bible is a waste of time.

I would like to conclude by saying that atheists who object to the cosmological fine-tuning argument really need to do their homework. Let’s see your better alternative universe, and let’s see your scientific explanation of how it works.