|

|

If Adam and Eve were real, who were they and when did they live? Nobody knows for sure. The proposals I have made below are tentative, and may be revised as new scientific information comes to light.

The case for Heidelberg man as Adam

(1) In keeping with the doctrine known as monogenesis (held by many Jews, Christians and Muslims), I shall assume that the entire human race is descended from a single original couple, Adam and Eve. This assumption is a theological rather than a scientific assumption; it is compatible with, but not entailed by, the theory of Intelligent Design. I have no intention of defending monogenesis in this article, as I have already done so in my Uncommon Descent posts, Do you have to believe in Adam and Eve? and Adam, Eve and the Concept of Humanity: A Response to Professor Kemp. See also this comment of mine for a brief review of the Scriptural difficulties associated with polygenism. It has been argued that science has ruled out the possibility of monogenesis (see Dennis Venema’s article, Does Genetics Point to a Single Primal Couple? for a non-technical summary of the evidence); for a response, see Dr. Ann Gauger’s chapter, “The Science of Adam and Eve,” in Science and Human Origins, by Ann Gauger, Douglas Axe, and Casey Luskin (Seattle, WA: Discovery Institute Press, 2012), pp. 105-122, and see also Dr. Robert Carter’s online article, Does Genetics Point to a Single Primal Couple? A response to claims to the contrary from BioLogos. For an online response to Francisco J. Ayala’s 1995 article, The Myth of Eve: Molecular Biology and Human Origins (Science 270: 1930–6), see here, here and here, and also here. For a response to Li and Durbin’s 2011 paper, Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences (Nature 475, 493–496 (28 July 2011), doi:10.1038/nature10231), see here. For a response to Blum and Jakobsson’s paper, Deep Divergences of Human Gene Trees and Models of Human Origins (Molecular Biology and Evolution (2011) 28(2): 889-898, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq265), see here. As I possess no competence in the field of genetics, I shall not discuss the scientific evidence any further here. Rather, my concern in this article is to identify the species to which Adam and Eve belonged and the time when they lived, assuming that they existed.

(2) I suggest that Adam and Eve were the first members of the species Homo heidelbergensis or Heidelberg man (pictured above, with a hand-axe made by Heidelberg man 500,000 years ago in Boxgrove, England, courtesy of Wikipedia), an ancient species of man found in Africa, Europe and Asia, which was distinct in its own right (see here and here) and which was the probable common ancestor of (a) modern Homo sapiens (who arose in Africa 200,000 years ago), (b) the Neandertals of Europe (who lived from at least 350,000 years ago to about 30,000 years ago), and possibly also (c) the Denisovans of Asia (who are believed to have broken off from the other lineages of human beings about one million years ago). These three species of man – some experts would classify them as subspecies – are known to have inter-bred with one another in the past (see here).

(3) I propose that Heidelberg man was the first hominid who, in addition to having a theory of mind (which earlier hominids may have had as well), was also capable of long-term planning, moral decision-making, the use of language and a symbolic culture. I shall defend this proposal below. I also claim that earlier hominids, such as Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, Homo ergaster and Homo erectus, lacked these capabilities.

(4) I hypothesize that Homo heidelbergensis, who is believed to have dispersed from Africa into Europe and western Asia around 780,000 years ago, arose in Africa over 1,000,000 years ago and more likely around 1,300,000 years ago (the oldest possible age for this species, according to Wikipedia). (At the present time, no fossils of Heidelberg man dating this far back are known, but since known Homo heidelbergensis fossils are relatively scarce, this fact shouldn’t surprise us. Species can predate their oldest known fossil specimens by quite a large margin.) The reason why I argue for Adam and Eve being at least one million years old is that although evidence from mitochondrial DNA indicates that all human beings shared a common female ancestor as recently as 140,000 years ago and analysis of Y-chromosomal DNA suggests that human beings share a common male ancestor who lived around 338,000 years ago (give or take 200,000 years), the common ancestors of our autosomal and X-chromosome-linked genes are much, much older, living, respectively, about 1,500,000 and 1,000,000 years ago (see M. G. B. Blum and M. Jakobsson, Deep Divergences of Human Gene Trees andModels of Human Origins, Molecular Biology and Evolution 28(2):889–898, 2011 doi:10.1093/molbev/msq265, and see supplementary material here). I should point out, however, that a fair deal of uncertainty attaches to these estimates: according to Blum and Jakobsson, there’s a 2.5% probability that the common ancestor of our autosomal genes lived as recently as 330,000 to 730,000 years ago, depending on which model of human ancestry one adopts (see Supplementary Material, Table 3).

If Heidelberg man appeared about 1.2 to 1.3 million years ago, this would roughly coincide with two events which are of possible Biblical significance: first, a massive increase in the number of sweat glands (enabling our ancestors to run long distances in pursuit of prey, without getting over-heated), which probably occurred at the time when our ancestors acquired smooth, hairless skin; and second, a total loss of body hair (which would have also helped our ancestors to radiate excess body heat), a process which was fully completed by 1,200,000 years ago at the latest (see here and here). In Genesis 2:25, we are told that Adam and Eve were naked when they were created, and in Genesis 3:19, we are told that Adam was condemned to work by the sweat of his brow. In Genesis 3:21, God clothes Adam and Eve in garments of skin. Recent studies indicate that modern Homo sapiens was wearing clothing at least 83,000 years ago and possibly as early as 170,000 years ago (see Origin of Clothing Lice Indicates Early Clothing Use by Anatomically Modern Humans in Africa by M. Toups, A. Kitchen, J. Light and D. Reed, in Molecular Biology and Evolution (2011) 28 (1): 29-32, doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq234). Unfortunately, the study could draw no firm conclusions for earlier species of Homo: “Whether these archaic hominins had clothing is unknown because they left no clothing louse descendents that we can sample among living humans.”

Another piece of pertinent Biblical evidence comes from Genesis 3:16, where Eve is told that she will suffer pain in childbearing. Homo erectus apparently did not have to contend with this problem. (See this press release: The First Female Homo erectus Pelvis, from Gona, Afar, Ethiopia, later published in the journal Science, 14 November, 2008.) However, childbirth would certainly have been painful for females of the larger-brained species, Homo heidelbergenesis (Heidelberg man), whose brain size was roughly equivalent to our own.

(5) I propose that the origin of Adam and Eve coincides with the appearance of human beings with 46 chromosomes in their body cells. Modern humans, Neandertals and Denisovans, who broke off from the lineages leading to Neandertal man and modern man at least 800,000 years ago, are known to have had 23 pairs of chromosomes in their body cells (or 46 chromosomes altogether), as opposed to the other great apes, which have 24 pairs (or 48 altogether). It is therefore highly likely that Heidelberg man, who is thought to have been the common ancestor of modern man, Neandertal man and Denisovan man, also had 23 pairs of chromosomes in his body cells – which would fit in with recent genetic evidence that hominids with 23 pairs of chromosomes first appeared some time between 3,000,000 and 740,000 years ago. In addition, the genetic differences between modern man, Neandertal man and Denisovan man are now known to have been slight: so slight that it has been suggested that they be grouped in one species, Homo sapiens (see here, here, here, here, but see also here).

In the Addendum below, following on a recent article published by anthropologist Evelyn Bowers, I argue that the transition from 48 chromosomes to 46 chromosomes in our hominid ancestors would have coincided with the emergence of a new species (but see this article by Dennis Venema for a contrary view). I propose that this species was Heidelberg man, the first true human being.

(6) Neandertal man is now known to have engaged in distinctively human cultural practices, such as wearing carefully sown clothing and footwear, burial of the dead (with personal ornaments and pigments, although this remains controversial), and the application of lumps of pigment to perforated shells. Unless we wish to say that human rationality arose on two independent occasions in human history, it is logical to infer that Heidelberg man, the last common ancestor of Neandertal man and modern man, was also rational.

In their review of recent research, titled, On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neandertal linguistic capacities and its consequences (in Frontiers in Psychology, 4:397. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00397), Dan Dediu and Stephen Levinson argue that the Neandertals’ advanced cultural behavior, coupled with their vocal capacity to produce language, suggests that they did in fact use language:

The Neandertals managed to live in hostile sub-Arctic conditions (Stewart, 2005). They controlled fire, and in addition to game, cooked and ate starchy foods of various kinds (Henry et al., 2010; Roebroeks and Villa, 2011). They almost certainly had sewn skin clothing and some kind of footgear (Sørensen, 2009). They hunted a range of large animals, probably by collective driving, and could bring down substantial game like buffalo and mammoth (Conard and Niven, 2001; Villa and Lenoir, 2009).

Neandertals buried their dead (Pettitt, 2002), with some but contested evidence for grave offerings and indications of cannibalism (Lalueza-Fox et al., 2010). Lumps of pigment — presumably used in body decoration, and recently found applied to perforated shells (Zilhao et al., 2010) — are also found in Neandertal sites. They also looked after the infirm and the sick, as shown by healed or permanent injuries (e.g., Spikins et al., 2010), and apparently used medicinal herbs (Hardy et al., 2012). They may have made huts, bone tools, and beads, but the evidence is more scattered (Klein, 2009), and seemed to live in small family groups and practice patrilocality (Lalueza-Fox et al., 2010)…

Neandertal culture, basically identical to modern human cultures before the Upper Paleolithic innovations, seems also to fall within the spectrum of modern human cultural variation in the ethnographic record. Various modern hunter-gatherers have produced archaeological records very similar or even considerably simpler than the Neandertal ones (Roebroeks and Verpoorte, 2009), some well-known examples being the North American early Archaic (Speth, 2004) and the Tasmanians (Richerson et al., 2009), who lacked bone tools, clothing, spear throwers, fishing gear, hafted tools and probably the ability to make fire (Henrich, 2004)…

Like these groups of modern humans with rather simple technology, the relative cultural simplicity of Neandertals compared to European modern humans can probably be best understood in its demographic context… In general, Neandertals had very low population densities, which coupled with the repeated local extinction and recolonization (Hublin and Roebroeks, 2009; Dennell et al., 2010; Dalén et al., 2012), would have inhibited the growth of complex technology….

Thus, we believe there is no argument to be made from Neandertal culture to the absence of language. The paucity of preserved symbolic material is also observed in early modern humans, and many modern ethnographic settings. On the contrary, nothing like Neandertal culture, with its complex tool assemblages and behavioral adaptation to sub-Arctic conditions, would have been possible without recognizably modern language.

(7) The making of Late Acheulean stone tools required complex hierarchical cognition, as well as the ability to plan action sequences in multiple stages. It also required bodily skills which could only have been acquired not merely as a result of observation, but through hundreds of hours of deliberate practice and experimentation. The making of Late Acheulean stone tools also activated areas of the brain which are known to have been involved in the production of language. This lends supports to the ‘technological pedagogy’ hypothesis, which proposes that intentional pedagogical demonstration could have provided an adequate scaffold for the evolution of intentional vocal communication.

Summarizing the results of recent research in their article, On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neandertal linguistic capacities and its consequences (in Frontiers in Psychology, 4:397. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00397), Dan Dediu and Stephen Levinson write:

The Neandertals had a complex stone tool technology (the Mousterian) that required considerable skill and training, with many variants and elaborations (see Klein, 2009: 485ff). They sometimes mined the raw materials at up to 2 meters depth (Verri et al., 2004). Their stone tools show wear indicating usage on wood, suggesting the existence of a wooden material culture with poor preservation, such as the carefully shaped javelins made ~400 kya [about 400,000 years ago – VJT] from Germany (Thieme, 1997). Tools were hafted with pitch extracted by fire (Roebroeks and Villa, 2011). Complex tool making of the Mousterian kind involves hierarchical planning with recursive sub-stages (Stout, 2011) which activates Broca’s area just as in analogous linguistic tasks (Stout and Chaminade, 2012). The chain of fifty or so actions and the motor control required to master it are not dissimilar to the complex cognition and motor control involved in language (and similarly takes months of learning to replicate by modern students).

I should point out that Dediu and Levinson believe that the human capacity for language appeared gradually, over a period of about one million years. While I agree with their claim that human language goes back approximately one million years, I maintain that its appearance was sudden: it literally happened overnight, due to an act of Intelligent Design on God’s part. Writer and columnist A. N. Wilson, a convert from atheism, argues that materialist accounts of the origin of language are inherently inadequate, in a hard-hitting article titled, Why I believe again (New Statesman, 2 April 2009):

The phenomenon of language alone should give us pause. A materialist Darwinian was having dinner with me a few years ago and we laughingly alluded to how, as years go by, one forgets names. Eager, as committed Darwinians often are, to testify on any occasion, my friend asserted: “It is because when we were simply anthropoid apes, there was no need to distinguish between one another by giving names.”

This credal confession struck me as just as superstitious as believing in the historicity of Noah’s Ark. More so, really.

Do materialists really think that language just “evolved”, like finches’ beaks, or have they simply never thought about the matter rationally? Where’s the evidence? How could it come about that human beings all agreed that particular grunts carried particular connotations? How could it have come about that groups of anthropoid apes developed the amazing morphological complexity of a single sentence, let alone the whole grammatical mystery which has engaged Chomsky and others in our lifetime and linguists for time out of mind? No, the existence of language is one of the many phenomena – of which love and music are the two strongest – which suggest that human beings are very much more than collections of meat.

A 2011 essay by Dietrich Stout and Thierry Chaminade, titled, Stone tools, language and the brain in human evolution (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 12 January 2012, vol. 367, no. 1585, pp. 75-87) lends support to the view that the Late Acheulean tools made by Heidelberg man required a high level of cognitive sophistication to produce, in addition to long hours of training for novices. This training would have included the use of intentional communication, which the authors characterize as “purposeful communication through demonstrations intended to impart generalizable (i.e. semantic) knowledge about technological means and goals, without necessarily involving pantomime.” The authors suggest that the production of these tools indicates the presence of “provides evidence of cognitive control processes that are computationally and anatomically similar to some of those involved in modern human discourse-level language processing,” but note that brain studies of modern people engaged in the act of producing these tools “have yet to reveal significant activation of ‘ventral stream’ semantic representations in the posterior temporal lobes,” leaving the question open as to whether the prehistoric creators of Late Acheulean tools would have needed to express the semantic content of their thoughts in sentences, when training novices:

Speech and tool use are both goal-directed motor acts. Like other motor actions, their execution and comprehension rely on neural circuits integrating sensory perception and motor control (figure 1). An obvious difference between speech and tool use is that the former typically occurs in an auditory and vocal modality, whereas the latter is predominantly visuospatial, somatosensory and manual. Nevertheless, there are important similarities in the way speech and tool-use networks are organized, including strong evidence of functional-anatomical overlap in IFG [inferior frontal gyrus] and, less decisively, in inferior parietal and posterior temporal cortex (PTC).

The similarity of cognitive processes and cortical networks involved in speech and tool use suggests that these behaviours are best seen as special cases in the more general domain of complex, goal-oriented action. This is exactly what would be predicted by hypotheses that posit specific co-evolutionary relationships between language and tool use (e.g. [4,6])…

We focused on two technologies, ‘Oldowan’ and ‘Late Acheulean’, that bracket the beginning and end of the Lower Palaeolithic, encompassing the first approximately 2.2 Myr (90%) of the archaeological record. Oldowan toolmaking is the earliest (2.6 Myr old [146]) known human technology and is accomplished by striking sharp stone ‘flakes’ from a cobble ‘core’ held in the non-dominant (hereafter left) hand through direct percussion with a ‘hammerstone’ held in the right hand. Late Acheulean toolmaking is a much more complicated method appearing about 700 000 years ago and involving, among other things, the intentional shaping of cores into thin and symmetrical teardrop-shaped tools called ‘handaxes’ [47]. We compared these technologies: (i) with a simple bimanual percussive control task in order to identify any distinctive demands associated with the controlled fracture of stone, and (ii) with each other in order to identify neural correlates of the increasing technological complexity documented by the archaeological record.

(a) Oldowan toolmaking

Results (figure 2) indicate that Oldowan toolmaking is especially demanding of ‘dorsal stream’ structures (§2a) involved in visuomotor grasp coordination, including anterior inferior parietal lobe and ventral premotor cortex but not more anterior IFG [44]. This is consistent both with behavioural evidence of the sensorimotor [147,148] and manipulative [46] complexity of Oldowan knapping, and with the concrete simplicity [149-151] and limited hierarchical depth [47] of Oldowan action sequences. Attempts to train a modern bonobo to make Oldowan tools [152] similarly indicate a relatively easy comprehension of the overall action plan but continuing difficulties with ‘lower-level’ perceptual-motor coordination and affordance detection.

(b) Late Acheulean toolmaking

The archaeologically attested ability of Late Acheulean hominins to implement hierarchically complex, multi-stage action sequences during handaxe production thus provides evidence of cognitive control processes that are computationally and anatomically similar to some of those involved in modern human discourse-level language processing.

Intentional communication

The … ‘technological pedagogy’ hypothesis proposes that in sufficiently complex praxis, goals are so distal and abstract that they must be inferred rather than observed. This provides a context for purposeful communication through demonstrations intended to impart generalizable (i.e. semantic) knowledge about technological means and goals [156], without necessarily involving pantomime…

…[W]e collected fMRI data from subjects of varying expertise observing an expert demonstrator producing Oldowan and Late Acheulean tools [47]… These effects of expertise and technological complexity suggest a model of complex action understanding in which the iterative refinement of internal models through alternating observation (i.e. inverse aspect of internal models) and behavioural approximation (i.e. practice comparing forward models with real feedback) allows for the construction of shared pragmatic skills and teleological understanding. The specific association of Late Acheulean action observation with inference of higher level intentions provides support for the technological pedagogy hypothesis and links it with a specific, archaeologically visible context.

Conclusion

Interestingly, functional imaging studies of Lower Palaeolithic toolmaking have yet to reveal significant activation of ‘ventral stream’ semantic representations in the posterior temporal lobes. This may be because experimental paradigms to date have strongly emphasized the ‘dorsal stream’ visuo-motor action aspects of tool production. However, if this trend continues in more diverse experimental manipulations, it may provide some support for the view that Lower Palaeolithic technology is relatively lacking in semantic content [35,36], and suggest that this aspect of modern human cognition evolved later and/or in a different behavioural context.

(8) As the common ancestor of Neandertals and modern human beings, Heidelberg man is now believed to have possessed the auditory specializations required for speech on the modern bandwidth, as well as larynx with a modern morphology, and a finely controlled pulmonic airstream mechanism for vocalization. In addition, the gene that is known to be involved in the fine motor control necessary for speech, FOXP2, has its modern form (although possibly not all of its modern regulatory environment). In their article, On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neandertal linguistic capacities and its consequences (in Frontiers in Psychology, 4:397. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00397), Dan Dediu and Stephen Levinson argue that this discovery strengthens the case for language use by other human species, in addition to Homo sapiens:

More important, however, is what the direct comparisons between the Neandertal, Denisovan and modern genomes can tell us about their similarities and differences. As expected given their recent common ancestry and their successful admixture, these three genomes are extremely similar, sharing the vast majority of innovations since the split from chimps… Potentially relevant for language and speech, they share for example the same “human specific” two amino-acid substitutions in FOXP2 (Krause et al., 2007), the best-known gene hitherto linked to language, lending support to our hypothesis that Neadertals were language users (Trinkaus, 2007).

Nevertheless, there are subtle differences between the genomes of the lineages: while the FOXP2 exons (the protein-coding sequences) are identical, recently Maricic et al. (2013) have reported that a regulatory element within intron 8 of FOXP2 binding the POU3F2 transcription factor differs between Neandertals and modern humans and might have been the target of recent positive selection since their split (Ptak et al., 2009). However, it is currently unclear what effects this change has and, importantly, the ancestral (“Neandertal”) allele is still present at ~10% frequency in present-day Africans (Maricic et al., 2013), showing that this variant is well within the modern human variation…

… [T]he genetic story so far suggests that Neandertals and Denisovans had the basic genetic underpinnings for recognizably modern language and speech, but it is possible that modern humans may outstrip them in some parameters (perhaps range of speech sounds or rapidity of speech, complexity of syntax, size of vocabularies, or the like).

(9) Heidelberg man must have practiced life-long monogamy, in order to rear children whose prolonged infancy and whose big brains, which required a lot of energy, would have made it impossible for their mothers to feed them without a committed husband who would provide for the family. Life-long monogamy in human beings requires a high level of self-control, which would be impossible without rationality. In his article, Paleolithic public goods games: why human culture and cooperation did not evolve in one step, Benoit Dubreuil argues that around 700,000 years ago, big-game hunting (which is highly rewarding in terms of food, if successful, but is also very dangerous for the hunters, who might easily get gored by the animals they are trying to kill) and life-long monogamy (for the rearing of children whose prolonged infancy and whose large, energy-demanding brains would have made it impossible for their mothers to feed them alone, without a committed husband who would provide for the family) became features of human life. Dubreuil refers to these two activities as “cooperative feeding” and “cooperative breeding,” and describes them as “Paleolithic public good games” (PPGGs).

(10) Heidelberg man is also known to have hunted big game – an activity which is highly rewarding in terms of food, if successful, but is also very dangerous for the hunters, who sometimes get gored by the animals they are trying to kill. While undertaking such a risky activity, the temptation to put one’s own life before the good of the group and to run away from a threatening-looking animal would have been high. Willingness to put one’s own life at risk for the good of the group presupposes the ability to keep selfish impulses in check, and to conceptualize the “greater good,” both of which would be impossible without rationality. Dubreuil (2010) argues that changes in the brain’s prefrontal cortex at the time when Heidelberg man first appeared were what made this impulse control possible. Dubreuil also argues in his paper that while there’s good evidence that Homo erectus ate a lot of meat, there’s no good evidence that he hunted large-scale game; probably he was an active scavenger, which means that he ate meat from carcasses that other animals had killed, and confronted any creature that tried to stop him eating.

Dubreuil is very wary of claims that human culture emerged in a single step (see his remarks below on Homo sapiens), but he thinks that the reorganization of the prefrontal cortex that enabled practices such as co-operative breeding and co-operative feeding to emerge may have occurred in a single step, with the dawn of Heidelberg man:

Our conclusions must thus remain relatively modest. Consequently, I will not claim that there has been a single reorganization of the PFC [prefrontal cortex – VJT] in the human lineage and that it happened in Homo heidelbergensis [Heidelberg man – VJT]. I will rather contend that, if there is only one point in our lineage where such reorganization happened, it was in all likelihood there.

(11) We now know that the prefrontal cortex of the human brain, which plays a vital role in planning, reasoning, problem solving and impulse control, was much the same in Heidelberg man as it is in modern man. In their article, Evolution of the Brain in Humans – Paleoneurology, Holloway et al. (2009) write: “The only difference between Neandertal and modern human endocasts is that the former are larger and more flattened. Most importantly, the Neandertal prefrontal lobe does not appear more primitive.”

Holloway et al. chronicle two earlier events in the evolution of the human brain:

At least two important reorganizational events occurred rather early in hominid evolution, (i) a reduction in the relative volume of primary visual striate cortex (PVC, area 17 of Brodmann), which occurred early in australopithecine taxa, perhaps as early as 3.5 MYA [million years ago – VJT] and (ii) a configuration of Broca’s region (Brodmann areas 44, 45, and 47) that appears human-like rather than apelike by about 1.8 MYA. At roughly this same time, cerebral asymmetries, as discussed above, are clearly present in early Homo taxa, starting with KNM-ER 1470, Homo rudolfensis…

Certainly, the second reorganizational pattern, involving Broca’s region, cerebral asymmetries of a modern human type and perhaps prefrontal lobe enlargement, strongly suggests selection operating on a more cohesive and cooperative social behavioral repertoire, with primitive language a clear possibility.

The authors go on to acknowledge, however, that “relative brain size was not yet at the modern human peak.”

Some creationists have argued that the brain size of Homo ergaster / erectus falls within the modern human range. As regards the earliest specimens of Homo ergaster / erectus, this claim is factually incorrect, and has been exposed here. To quote:

Hrdlicka (1939) examined the extremes of brain size in the 12,000 American skulls stored in the U.S. National Museum collections. Of these, the smallest 29, or fewer than 1 in 400, ranged from 910 to 1050 cc. Hrdlicka states that the smallest skull in this collection, at 910 cc, appears to be the lowest volume ever measured for a normal human cranium.

Compare the above figures with the 5 measurable Java Man skulls. These average 930 cc, … with the smallest being 815 cc.

I should add that the average brain size of Homo ergaster / erectus specimens in Africa, dating from 1.8 to 1.5 million years ago, is a mere 863 cubic centimeters, while that of Georgian specimens of Homo ergaster / erectus dating from 1.8 to 1.7 million years ago is even lower, at 686 cubic centimeters (see this chart by Susan C. Antón and J. Josh Snodgrass, from Origins and Evolution of Genus Homo: New Perspectives, in Current Anthropology, Vol. 53, No. S6, “Human Biology and the Origins of Homo,” December 2012, pp. S479-S496). By comparison, the brain size of early Homo specimens (excluding 1470 man) is 629 cubic centimeters. Quite clearly, these fall well outside the modern human range. Quite clearly, also, there is no evidence for a sudden jump in brain size from Australopithecus afarensis (whose average brain size was 478 cubic centimeters) to Homo ergaster / erectus. The brain size of early Homo (who lived around 2.3 million years ago) is intermediate between the two.

It is certainly true that something very important in human evolution occurred 1.8 million years ago, in terms of brain evolution: our brains started getting bigger than they should have been, for a primate of our size. I would refer interested readers to an article titled, How Our Ancestors Broke through the Gray Ceiling by Karin Isler and Carel P. van Schaik, in Current Anthropology, Vol. 53, No. S6, “Human Biology and the Origins of Homo” (December 2012), pp. S453-S465. The authors argue that by rights, hominid brains should have stopped growing when they reached 700 cubic centimeters, but that our ancestors somehow broke through this threshold. The authors contend that co-operative breeding was the behavioral change that made this possible. On that score, they are probably correct; however, there exists considerable disagreement among anthropologists as to what kind of co-operative breeding it was. Was it grandmothers helping mothers to find food for their newborn babies, or was it fathers helping mothers, and making a commitment to stay together for the long term? Or was it a combination of both?

In their paper, Grandmothering and Female Coalitions: A Basis for Matrilineal Priority? (in Allen, N. J., Callan, H., Dunbar, R. and James, W. (eds), Early Human Kinship: From Sex to Social Reproduction, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford, UK, 2009), Kit Opie and Camilla Power identify four distinct stages in hominid evolution. In the first stage, energy requirements were relatively low, and mothers were self-sufficient foragers. In the second phase, as babies’ brains grew bigger and required more energy, mothers required the assistance of grandmothers, in caring for their infants. In the third phase, with the emergence of Homo erectus, adults (especially females) had considerably larger bodies, with much higher energy requirements. By now, Opie and Power argue, some degree of male co-operation in child-rearing had become a practical necessity, but no long-term monogamous commitment would have been required: during this stage, “[m]embers of each sex are likely to ‘trade’ with more than one partner.” In the fourth and final phase, with the emergence of Heidelberg man (who was as tall as we are and who had a brain capacity averaging around 1250 cc.), the human brain finally reached a size that fell within the modern range of 1000 to 1500 cc. The bigger brains of children would have placed an even greater load upon mothers, who would have been utterly unable to provide for their infants without the presence of a committed father. At the same time, females developed co-operative strategies among themselves to discourage male philandering. It was at about this time that cosmetics are believed to have appeared: red ochre, the authors suggest, was originally used to attract males.

If Opie and Power are right, then only when we get to Heidelberg man, whose brain size falls within the modern human range, does the energetic cost of raising an infant become so great that the commitment of monogamy would have been an absolute necessity for successful child-rearing. It can truly be said, then, that without the long-term commitment of monogamy, our brains would never have developed to their present size.

(12) It has often been claimed that Heidelberg man did not create any art. However, according to a 2011 paper, The First Appearance of Symmetry in the Human Lineage: where Perception meets Art (careful: large file!) by Dr. Derek Hodgson (in Symmetry, 2011, 3, 37-53; doi:10.3390/3010037), tools dating from 750,000 years ago, which were created either by Heidelberg man or late Homo erectus, have been unearthed in Africa, which manifest a concern for three-dimensional symmetry on the part of their makers, which is a clear indication of artistic ability. (See also the discussion of the Master hand-axe here.) In addition, “red ochre, a mineral that can be used to create a red pigment which is useful as a paint, has been found at Terra Amata excavations in the south of France” (Wikipedia), although this claim is controversial (see here). Finally, a fragment of bone (an elephant tibia) with two groups of 7 and 14 incised parallel lines, dating from 370,000 years ago, has been found at the site of Bilzingsleben in Germany, and some researchers have suggested that it represents an early example of art. Controversially, John Feliks goes much further: he argues that they reflect “graphic skills far more advanced than those of the average modern Homo sapiens,” including “abstract and numeric thinking; rhythmic thinking; ability to duplicate not only complex, but also, subtle motifs; iconic and abstract representation; exactly duplicated subtle angles; exactly duplicated measured lines; innovative artistic variation of motifs including compound construction, doubling, diminution, and augmentation; understanding of radial and fractal symmetries; impeccably referenced multiple adjacent angles; and absolute graphic precision by high standard and, practically, without error.” (See his Website here.) Although the skeletal remains found at Bilzingsleben are often said to be those of Homo erectus (an identification accepted by Feliks), this identification is not certain and the recent date accords better with Heidelberg man.

Could Adam have been Homo ergaster / erectus?

|

Skull of Homo erectus, Museum of Natural History, Ann Arbor, Michigan, November 2007. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Is there a sharp anatomical discontinuity between Homo ergaster / erectus and earlier hominids?

It has been argued that the appearance of Homo ergaster / erectus represents a sudden leap in the fossil record, which some old earth creationists and Intelligent Design proponents have taken to coincide with the appearance of the first true human beings. For a recent defense of the view that Homo ergaster / erectus appears abruptly in the fossil record, and that his anatomy is sharply distinct from that of Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis (a.k.a. 1470 man), see Casey Luskin’s essay, Read Your References Carefully: Paul McBride’s Prized Citation on Skull-Sizes Supports My Thesis, Not His (Evolution News and Views, August 31, 2012).

Until a few years ago, many anthropologists believed that there were stark anatomical differences between Australopithecus and Homo erectus, and many of them also believed that Homo habilis should be classified as a species of Australopithecus. Oft-cited in this regard is a 2000 paper by J. Hawks, K. Hunley, S.H. Lee, and M. Wolpoff, titled, Population bottlenecks and Pleistocene human evolution (Molecular Biology and Evolution 17(1):2–22), in which the authors write: “We, like many others, interpret the anatomical evidence to show that early H. sapiens was significantly and dramatically different from earlier and penecontemporary australopithecines in virtually every element of its skeleton (fig. 1) and every remnant of its behavior…” In support of their claim, the authors cited the work of Bernard A. Wood and Mark Collard, who put forward powerful arguments for this view in 1999, in their paper, The human genus (Science Vol. 284 no. 5411 pp. 65-71). However, I should mention that while Wood and Collard found major anatomical differences between Homo habilis in six broad categories of traits – body size, body shape, locomotion, jaws & teeth, development, and brain size – three of those traits could not be assessed for another species of early Homo, Homo rudolfensis. (See this table, which summarizes their findings.) Wood and Collard defended their view that Homo erectus represented a clean break from his hominid predecessors once again in their 2001 paper, The Meaning of Homo (Ludus vitalis, vol. IX, no. 15, 2001, pp. 63-74) and more recently, in their 2007 paper, Defining the genus Homo (in Henke, W. and Rothe, H. and Tattersall, I., (eds.) Handbook of Paleoanthropology, Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, pp. 1575-1610).

The scenario proposed by Wood and Collard and is now out of date. Recent papers published in 2012 – see Early Homo: Who, When, and Where (by Susan C. Antón, in Current Anthropology, Vol. 53, No. S6, “Human Biology and the Origins of Homo,” December 2012, pp. S278-S298), Origins and Evolution of Genus Homo: New Perspectives (by Susan C. Antón and J. Josh Snodgrass, in Current Anthropology, Vol. 53, No. S6, “Human Biology and the Origins of Homo,” December 2012, pp. S479-S496) and Human Biology and the Origins of Homo: An Introduction to Supplement 6 (by Leslie C. Aiello and Susan C. Antón, in Current Anthropology, Vol. 53, No. S6, “Human Biology and the Origins of Homo,” December 2012, pp. S269-S277) show that the transition from Homo habilis to early Homo ergaster / erectus was not much larger than that between Australopithecus and Homo habilis. A detailed anatomical comparison – see this chart by Susan C. Antón and J. Josh Snodgrass, from Origins and Evolution of Genus Homo: New Perspectives, in Current Anthropology, Vol. 53, No. S6, “Human Biology and the Origins of Homo,” December 2012, pp. S479-S496) – indicates that the transition from Australopithecus to early Homo, who appeared about 2.3 or 2.4 million years ago, and from early Homo to Homo ergaster / erectus, is much smoother and more gradual than what anthropologists believed it to be, ten years ago. The above-cited 2012 article by Susan C. Antón and J. Josh Snodgrass, titled, Origins and Evolution of Genus Homo: New Perspectives, conveys the tenor of the new view among anthropologists:

Recent fossil and archaeological finds have complicated our interpretation of the origin and early evolution of genus Homo. It now appears overly simplistic to view the origin of Homo erectus as a punctuated event characterized by a radical shift in biology and behavior (Aiello and Antón 2012; Antón 2012; Holliday 2012; Pontzer 2012; Schwartz 2012; Ungar 2012). Several of the key morphological, behavioral, and life history characteristics thought to first emerge with H. erectus (e.g., narrow bi-iliac breadth, relatively long legs, and a more “modern” pattern of growth) seem instead to have arisen at different times and in different species…

Over the past several decades, a consensus had emerged that the shift to humanlike patterns of body size and shape — and at least some of the behavioral parts of the “human package” — occurred with the origin of Homo erectus (e.g., Antón 2003; Shipman and Walker 1989). This was seen by many researchers as a radical transformation reflecting a sharp and fundamental shift in niche occupation, and it emphasized a distinct division between H. erectus on the one hand and non-erectus early Homo and Australopithecus on the other. Earliest Homo and Australopithecus were reconstructed as essentially bipedal apes, whereas H. erectus had many of the anatomical and life history hallmarks seen in modern humans. To some, the gap between these groups suggested that earlier species such as Homo habilis should be excluded from Homo (Collard and Wood 2007; Wood and Collard 1999).

Recent fossil discoveries paint a picture that is substantially more complicated. These discoveries include new fossils of H. erectus that reveal great variation in the species, including small-bodied members from both Africa and Georgia (Gabunia et al. 2000; Potts et al. 2004; Simpson et al. 2008; Spoor et al. 2007), and suggest a previous overreliance on the Nariokotome skeleton (KNM-WT-15000) in reconstructions of H. erectus. Additionally, reassessments of the Nariokotome material have concluded that he would have been considerably shorter than previous estimates (∼163 cm [5 feet 4 inches], not 185 cm [6 feet 1 inch]; Graves et al. 2010), younger at death (∼8 years old, not 11–13 years old; Dean and Smith 2009), and with a life history pattern distinct from modern humans (Dean and Smith 2009; Dean et al. 2001; Thompson and Nelson 2011), although we note that there is substantial variation in the modern human pattern of development (Šešelj 2011). Further, the recent discovery of a nearly complete adult female H. erectus pelvis from Gona, Ethiopia, which is broad and has a relatively large birth canal, raises questions about the narrow-hipped, Nariokotome-based pelvic reconstruction and whether H. erectus infants were secondarily altricial (Graves et al. 2010; Simpson et al. 2008).2

Finally, from a purely anatomical standpoint (as opposed to a neurological or genetic standpoint), there is no significant gap between Homo ergaster / erectus and Heidelberg man.

Boat-building, fishing and cooking with fire: did Homo ergaster / erectus possess a culture requiring the use of reason?

Some authors have contended that prior to Heidelberg man, Homo ergaster / erectus was also capable of a highly sophisticated culture requiring the use of reason, but this claim remains doubtful, on the basis of current evidence.

For instance, it has been argued (see here and here) that Homo erectus was capable of building boats, and that this is how he managed to travel almost 20 kilometers, from the island of Java – which was joined to Borneo and Sumatra during the Ice Ages – to the Indonesian island of Flores, some 800,000 years ago, where he then evolved into the small-brained hominid Homo floresiensis, popularly known as the Hobbit. However, a healthy dose of skepticism is in order here: it is quite possible that he simply latched onto an already floating log or tree, and as luck would have it, ended up in Flores. A blog article by Erin Wayman in Smithsonian.com magazine, titled, Were the Hobbits’ Ancestors Sailors? (July 9, 2012), canvasses the various possibilities:

One possibility is that the Hobbits’ forefathers sailed over on a raft. Or their arrival might have been an act of nature: A powerful storm or tsunami could have washed a small group of hominids out to sea, and then floating vegetation carried them to Flores. That idea sounds implausible, but it’s also an explanation for how monkeys reached South America.

In her article, Wayman also discusses a recent study, titled, Population trajectories for accidental versus planned colonisation of islands by Graeme Ruxton and David Wilkinson, (in the Journal of Human Evolution, Volume 63, Issue 3, September 2012, Pages 507–511) which assessed the relative likelihood of the two hypotheses that the island of Flores was settled by castaways arriving on vegetation rafts after major floods or a tsunami, or by a planned colonization of people traveling in boats. The study’s conclusion is ambiguous, as Wayman reports:

…[T]he results indicate that both rafting and accidental ocean dispersals are possible explanations for the Hobbits’ inhabitation of Flores. Therefore, the researchers warn, a hominid’s presence on an island isn’t necessarily evidence of some kind of sailing technology.

Fishing has also been attributed to Homo erectus, on the basis of recent excavations in northern Israel in 2010, showing that fishing was practiced 750,000 years ago. However, scientists have yet to determine whether it was Homo erectus or Heidelberg man who engaged in fishing at this early date.

Finally, it has been claimed that human beings were capable of the controlled use of fire over one million years ago, during the early Acheulean, implying that Homo erectus was the first to master this complex technical feat. (See here for a news report. More details can be found in the paper, Microstratigraphic evidence of in situ fire in the Acheulean strata of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa by F. Berna et al., PNAS, April 2, 2012, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117620109.) The recently reported evidence for the controlled use of fire at Wonderwerk cave in South Africa has impressed some anthropologists. Others, however, are more skeptical. Wil Roebroeks of Leiden University in the Netherlands and Paola Villa, a curator at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History in the U.S, commented as follows: “Is the Wonderwerk evidence good enough to suggest that hominins a million years ago were regular fire users all through their range? A definite ‘no’ – we do not have the evidence to back up such a claim, before 400,000 years ago.” The more recent date of 400,000 years ago means that the controlled use of fire was an innovation that may well have been due to Heidelberg man.

It has been claimed that Homo ergaster / erectus was capable of cooking with fire at least 1.9 million years ago. In a recent paper titled, Phylogenetic rate shifts in feeding time during the evolution of Homo, by Chris Organ, C. Nunn, Z. Machanda and R. Wrangham, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, August 22, 2011, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107806108, it is argued that since modern humans spend an order of magnitude less time feeding than predicted by phylogeny and body mass (4.7% vs. predicted 48% of daily activity), a substantial evolutionary rate change in feeding time must have occurred along the human branch after the human–chimpanzee split. The authors reason that since processed food is much easier to chew and digest, the ancestors of modern humans who invented food processing (including cooking) would have gained critical advantages in survival and fitness through increased caloric intake. The authors demonstrate that Homo erectus shows a marked reduction in molar size that is followed by a gradual, although erratic, decline in H. sapiens, and they argue that this change cannot be explained by craniodental and body size evolution alone. The authors conclude that cooking was commonplace among Homo erectus, and that it may well go back to Homo habilis. A non-technical summary of the authors’ research can be found in a report in The Guardian by Ian Samples (Cooking may be 1.9m years old, say scientists, 22 August 2011). However, one of the authors of the study, Chris Organ of Harvard University, has admitted in an interview with Jennifer Welsh of LiveScience (Man Entered the Kitchen 1.9 Million Years Ago, 22 August 2011) that the cooking hypothesis has one serious snag:

“There isn’t a lot of good evidence for fire. That’s kind of controversial,” Organ said. “That’s one of the holes in this cooking hypothesis. If those species right then were cooking you should find evidence for hearths and fire pits.”

Another problem with the hypothesis is that if it is correct, then Homo habilis probably cooked with fire too – which seems rather unlikely, given the creature’s relatively small brain size.

Perhaps the best evidence for cognitive sophistication in Homo ergaster / erectus lies in the fact that this hominid transported rock over a distance of 12-13 hilometers, compared with just tens or hundreds of meters for Australopithecus and early Homo (see here). This does indeed suggest a certain degree of foresight on the part of Homo ergaster / erectus, but it can hardly be considered definitive proof.

The origin of human compassion

Evidence for human compassion certainly goes back to Heidelberg man; whether it goes back to Homo erectus is more controversial. In a thought-provoking essay titled, From Hominity to Humanity: Compassion from the earliest archaic to modern humans (Time and Mind 3 (3), November 2010), authors P.A. Spikins, H. E. Rutherford and A. P. Needham begin by acknowledging the existence of compassionate feelings in non-human animals, but point out one vital difference:

Compassion in other animals is comparatively fleeting, for example chimpanzees don’t make allowances for individuals who are slow or who cannot keep up with the group, nor do they ‘think through’ how to help others in the long term. Yet in contrast compassion is fundamental to human social life. Simon Baron-Cohen and Sally Wheelwright call it ‘the glue that holds society together’ and it is fair to say that compassionate responses and reciprocal altruism forms the basis of all close human social relationships…

Most particularly we notice that unlike in other primates, compassionate motivations in humans extend into the long term. We can both feel compassion and be motivated to help someone, and at the same time ‘think through’ what to do. That is, we are able to ‘regulate’ compassion, to talk about how we feel, and to bring compassionate motivations to help others into rational thought and plan ahead for the long term good of someone we care for.

In chapter three of their essay, Spikins et al. propose a four-stage model of the evolution of human compassion. In the first stage, individuals are aware of one another’s feelings and immediate intentions, and assist one another. However, their compassion is not yet rational; it is a short-lived emotion in response to another individual’s distress. In the second stage, compassion is “extended widely into non-kin and in potentially extensive investments in caring for offspring and equally for ill individuals,” with the result that “[t]hose who were incapacitated might be provisioned with food for at least several weeks if not longer.” Spikins et al. go on to posit a third stage in the evolution of human compassion, during which human existence was characterized by “a long period of adolescence and a dependence on collaborative hunting”; hence “compassion extends into deep seated commitments to the welfare of others.” In the fourth and final stage, human compassion took a new turn: it was now directed at objects, in addition to being directed at people – “the capacity for compassion extends into strangers, animals, objects and abstract concepts.” The final stage does not suggest any increase in empathy to me, but simply an increase in imagination, so I’d like to focus on the third.

In chapter two of their essay, Spikins et al. also discuss the case of a Homo heidelbergensis girl (known as Cranium 14) from Sima de los Huesos, Spain, who lived 530,000 years ago, and who suffered from lambdoid single suture craniosynostosis, a premature closing of the bony elements of the skull. This would have caused an increase of pressure within the brain of this child, which would have stunted her brain growth and probably her mental capacity as well, in addition to altering her facial appearance. Despite these severe afflictions, and despite her inability to contribute to society, the young girl received care for at least five years before dying. That is certainly highly suggestive of empathy.

The fossil remains discussed above fit a broad picture of sick and/or injured fossil individuals dating from the Early and Middle Pleistocene period, who were obviously taken care of for an extended period of time, by members of their community. (Most of these sick and injured individuals belonged to the species Homo heidelbergensis, and in some cases, Homo ergaster / erectus.) Until recently, evidence for this uniquely human kind of compassion was largely confined to the late Pleistocene period, when Neandertal man and Homo sapiens lived. Anthropologists Hong Shang and Erik Trinkaus lend further support to the new picture in their paper, An Ectocranial Lesion on the Middle Pleistocene Human Cranium From Hulu Cave, Nanjing, China (American Journal of Physical Anthropology 135:431-437, 2008), in which they describe the case of a healed lesion in the skull of an unfortunate individual living in China about 577,000 years ago, who suffered a very severe, localized head trauma caused by “a traumatic alteration of the anterior scalp, a serious neurocranial burn some time before death, and/or (but less likely) a large scale periosteal reaction.” Commenting on the specimen, the authors write:

The Hulu 1 cranium therefore joins a growing series of Pleistocene human remains with nontrivial pathological alterations. There is a number of cases of such skeletal changes among Late Pleistocene archaic and modern humans (e.g., Trinkaus, 1983; Duday and Arensburg, 1991; Berger and Trinkaus, 1995; Kricun et al., 1999; Tillier, 1999; Schultz, 2006; Trinkaus et al., 2006). In addition, such cases are becoming increasingly documented for Early and Middle Pleistocene human remains. These earlier ones include probable dietary deficiencies…, developmental abnormalities…, an infectious disorder…, cranial lesions … and serious dentoalveolar abnormalities…

Together these remains document the probably high level of risk to which these pre-Late Pleistocene humans were subjected. These remains also document their ability to survive both minor and major abnormalities, since all of these lesions document some degree of survival.

In their 2010 paper, Spikins et al. describe an even earlier example of possible long term care from Dmanisi in Georgia, 1.77 million years ago: an early Homo ergaster / erectus female had lost all but one tooth, several years before her death, with all the sockets except for the canine teeth having been re-absorbed. This individual could only have consumed soft plant or animal foods. Probably she was reliant on support from others. However, it should be pointed out that chimpanzees can sometimes survive the loss of some teeth for a while, too. It thus remains questionable whether Homo ergaster / erectus was capable of true compassion, in the human sense of the word.

To sum up: while there is persuasive evidence for human compassion in Heidelberg man, the case for compassion in Homo ergaster / erectus remains undecided.

A final caveat: what if I’m wrong about the existence of rationality in Heidelberg man?

|

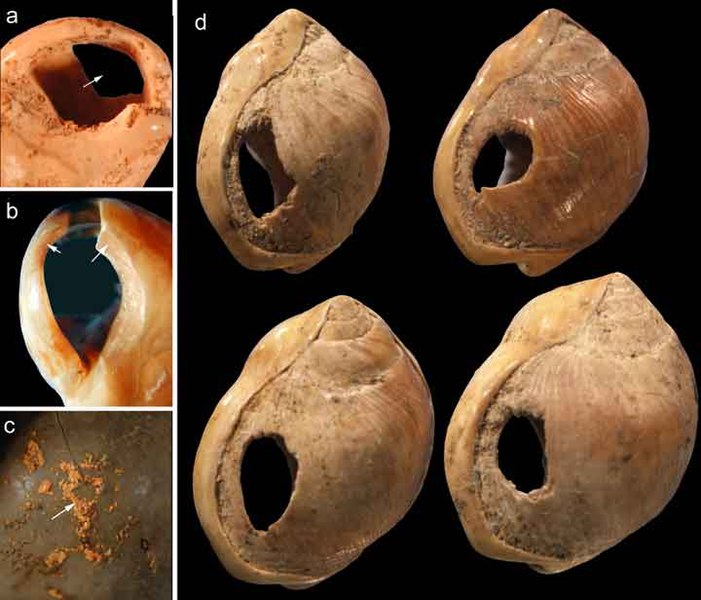

75,000 year old shell beads from Blombos Cave, South Africa, made by Homo sapiens. Image courtesy of Chris Henshilwood, Francesco d’Errico and Wikipedia.

I would like to conclude this article with a caveat of my own. The science of human origins is a speculative enterprise, and any theological conclusion built on such a foundation is speculation piled on top of speculation. For this reason, I would like to acknowledge that it is quite possible that I am mistaken about the rationality of Heidelberg man and even Neandertal man. There is some evidence that Heidelberg man did not possess the same symbolic and artistic capacities as Homo sapiens; the question we need to confront is whether the difference between the two is merely one of degree (which would not matter, theologically speaking) or rather, one of kind. Regarding this point, I’d like to cite Dubreuil (2010):

The relative stability of the PFC [prefrontal cortex] during the last 500,000 years can be contrasted with changes in other brain areas. One of the most distinctive features of Homo sapiens’ cranium morphology is its overall more globular structure. This globularization of Homo sapiens’ cranium occurred between 300,[000] and 100,000 years ago and has been associated with the relative enlargement of the temporal and/or parietal lobes (Lieberman et al. 2002; Bruner et al. 2003; Bruner 2004, 2007; Lieberman 2008). (p. 67)

The temporoparietal cortex is certainly involved in many complex cognitive tasks. It plays a central role in attention shifting, perspective taking, episodic memory, and theory of mind (as mentioned in Section “The role of perspective taking”), as well as in complex categorization and semantic processing (that is where Wernicke’s area is located)…

I have argued elsewhere (Dubreuil 2008; Henshilwood and Dubreuil 2009) that a change in the attentional abilities underlying perspective taking and high-level theory of mind best explains the behavioral changes associated with modern Homo sapiens, including the evolution of symbolic and artistic components in material culture. (p. 68)

I should point out too that Dediu and Levinson’s 2013 paper has been critiqued by Berwick, Hauser and Tattersall, who argue in their commentary that: (i) “hominids can be smart without implying modern cognition”; (ii) “smart does not necessarily mean that Neanderthals had the competence for language or the capacity to externalize it in speech”; (iii) the earliest unambiguous evidence for symbolic communication dates from less than 100,000 years ago; and (iv) although they may have had the same FOXP2 genes as we do, “[n]either Neanderthals nor Denisovans possessed human variants of other putatively ‘language-related’ alleles such as CNTAP2, ASPM, and MCPH1.”

In a recent paper, Somel et al. (2013) argue that human-specific cognitive abilities arose around 200,000 years ago, subsequent to the split between Neandertals and Homo sapiens:

With respect to the trajectory of human brain evolution, the existing data suggest two distinct phases: a long and gradual increase in brain size that was accompanied by cortical reorganization, followed by a more recent phase of region-specific developmental remodelling. This second phase, which led to the emergence of the cognitive traits that produced the human cultural explosion ~200,000 years ago, may have been driven by only a few mutations that affected the expression and/or primary structure of developmental regulators.

However, Somel et al. acknowledge that “it is conceivable that Neanderthals and Denisovans also possessed certain types of human-like linguistic abilities.”

To back up their claim for a “rapid cultural explosion observed in the archaeological record that started approximately 250 kya [thousand years ago],” the authors write: “With the rise of modern humans in Africa, between 250 and 50 kya, bone tools began to be exploited, and spear heads and fishing appeared.” But recent excavations in Israel suggest that fishing arose 750,000 years ago, while recent evidence suggests that stone-tipped spears were first made at least 500,000 years ago.

The authors also concede (see Box 4) that the number of genetic changes underlying changes in cognitive abilities that could have taken place after separation of the human and Neanderthal lineages would have been very small – about four or less. They suggest that MEF2A may play “a master role in the regulation of the human-specific

delay in the expression of synaptic genes in the PFC [prefrontal cortex]”, allowing synapses to mature more slowly in the brains of human infants, and they point out that there are indications that human-specific changes in MEF2A expression may have taken place after the human–Neanderthal split. (Synapses take five years to mature in humans, but only a few months in chimpanzees and macaque monkeys.) They also suggest that a FOXP2 regulatory mutation about 250,000 years ago (subsequent to the earlier amino acid mutation, shared by Neandertals, that probably occurred about 1 million years ago) may have facilitated the development of modern language. But the paper they cite on FOXP2 is highly speculative and avoids drawing conclusions. Finally, the authors’ evidence for changes in MEF2A expression subsequent to the split between the Neandertals and Homo sapiens consists in the fact that modern man has more genetic variants in a particular region of this gene. This is hardly compelling evidence. It is intriguing, however, that “among 23 genes harbouring amino acid changes at conserved positions that are human-specific and not shared with Denisovans, eight have roles in neural and synaptic development” (p. 119). What needs to be determined is whether mutations in these genes would make a qualitative rather than a merely quantitative difference to human cognitive abilities.

In his 2012 book, Masters of the Planet, paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall American Museum of Natural History argues that Homo sapiens had a highly distinctive appearance which marks him out from other hominids: “[e]ven allowing for the poor record we have of our close extinct kin, Homo sapiens appears as distinctive and unprecedented.” It is true that if one places the skull of Heidelberg man (Homo sapiens‘s presumed predecessor) alongside a skull of modern man, the differences between the two do indeed look pretty startling (see here for a good example, taken from a very well-argued article by Melissa Cain Travis). However, the Heidelberg man skull in her illustration is an extreme example: it’s the Kabwe skull (formerly known as Rhodesian man). Other skulls of Heidelberg man look more modern – for instance, this skull of Petralona man (now thought to be 350,000 years old, not 120,000, 200,000 or 700,000 as once claimed). The Steinheim skull, which is 250,000 years old, also looks similar to Homo sapiens. One should therefore be wary of saying that Homo sapiens is absolutely unprecedented in the fossil record.

Addendum: Why the emergence of individuals with 46 chromosomes in their body cells would have constituted a biological barrier to reproduction

Physical anthropologists believe that at some stage in our evolutionary past, ancestral chromosomes 2A and 2B fused to produce human chromosome 2. This would have caused a reproductive barrier between the early humans who had 46 chromosomes in their body cells and closely related hominids who had 48. This reproductive barrier is described in a paper entitled, “A Genetic Model for the Origin of Hominid Bipedality” by Dr. Evelyn J. Bowers (Department of Anthropology, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana), in New Perspectives and Problems in Anthropology, edited by Eva B. Bodzsar and Annamaria Zsakai, 2007, Cambridge Scholars Publishing (pp. 4-5). Bowers contends that this barrier coincided with the emergence of bipedalism in the human line:

I have previously proposed that the origin of our lineage and the origin of bipedality coincide and are the consequence of the chromosomal fusion which produced our second chromosome from what are the 12th and 13th chromosomes in chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans (Bowers in press 2004). Some years ago Mary-Clare King and colleagues proposed a highly plausible mechanism for rapid speciation based on chromosomal fusion (King and Wilson 1975, Wilson, Bush, Case and King 1975). If a chromosomal fusion occurs in the male in an inbreeding single-male-multiple-female social group in which the young disperse, the stage is set for an abrupt speciation event. Only a third of gametes formed by an individual with a fusion carry a normal chromosome compliment (Stine 1989). Zygotes formed by the other two thirds will be inviable (sic). Of the viable third, half the offspring by a non-fusion individual will be expected to carry the fusion. Figure 1-1 shows what happens in the next generation, when both the male and some of the females carries the fusion. Of 36 possible chromosome combinations in their zygotes, eight can be expected to be viable where both parents carry the fusion. Of these, seven will have at least one copy of the fusion chromosome. This looks to be a prescription for abrupt speciation. I think this kind [of] chromosomal fusion is what produced our line.

It is reasonable to suppose, then, that the sudden appearance of a hominid with 46 chromosomes per body cell, instead of 48 as in chimps and gorillas, would have constituted the emergence of a new species. (Bowers believes that this species could have propagated rapidly, as a result of a single male breeding with multiple females; that is not my view.)

One obvious flaw in Bowers’ bipedality hypothesis is that the fusion of chromosome 2 seems to have occurred much later than the origin of bipedality, which occurred at least four million years ago. According to recent research, the ancestors of modern human beings underwent a change from 48 to 46 chromosomes per body cell, somewhere between 740,000 and 3,000,000 years ago – i.e. probably around the time when Homo erectus emerged, although it could have coincided with the date of Homo heidelbergensis. (Reference: Biased clustered substitutions in the human genome: The footprints of male-driven biased gene conversion by Timothy R. Dreszer, Gregory D. Wall, David Haussler and Katherine S. Pollard. In Genome Research 2007. 17: 1420-1430.) Nevertheless, Bowers’ point that the change from 48 to 46 chromosomes would have given rise to a major barrier to reproduction remains a valid one.

Recommended Reading

On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neandertal linguistic capacities and its consequences by Dan Dediu and Stephen Levinson, in Frontiers in Psychology, 4:397. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00397.

Neanderthal language? Just-so stories take center stage by Robert C. Berwick, Marc D. Hauser and Ian Tattersall, in Frontiers in Psychology, 4:671. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00671.

Evolution of the Brain in Humans – Paleoneurology by Ralph Holloway, Chet Sherwood, Patrick Hof and James Rilling (in The New Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, Springer, 2009, pp. 1326-1334).

Paleolithic public goods games: why human culture and cooperation did not evolve in one step by Benoit Dubreuil, in Biology and Philosophy (2010) 25:53–73, doi 10.1007/s10539-009-9177-7.

Human brain evolution: transcripts, metabolites and their regulators by M. Somel, X. Liu, and P. Khaitovich, in (2013) Nature Reviews Neuroscience 14, 112–127, (February 2013), doi: 10.1038/nrn3372. The full version is available online.

Stone toolmaking and the evolution of human culture and cognition by Dietrich Stout, in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 12 April 2011, vol. 366, no. 1567, pp. 1050-1059 (doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0369).

Stone tools, language and the brain in human evolution by Dietrich Stout, and Thierry Chaminade, 21 November 2011 in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 12 January 2012 vol. 367 no. 1585 75-87 (doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0099).

The First Appearance of Symmetry in the Human Lineage: where Perception meets Art (careful: large file!) by Dr. Derek Hodgson. In Symmetry, 2011, 3, 37-53; doi:10.3390/3010037