|

|

Here’s a question for skeptics. Is there any evidence that would convince you that the laws of Nature can be suspended, and that miracles do indeed occur?

Interestingly, modern-day skeptics are divided on this issue. Professor P. Z. Myers and Dr. Michael Shermer say that nothing would convince them; while Professor Jerry Coyne and Professor Sean Carroll say that if the evidence were good enough, they would provisionally accept the reality of the supernatural. (See here and here for a round-up of their views.)

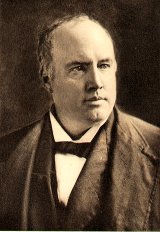

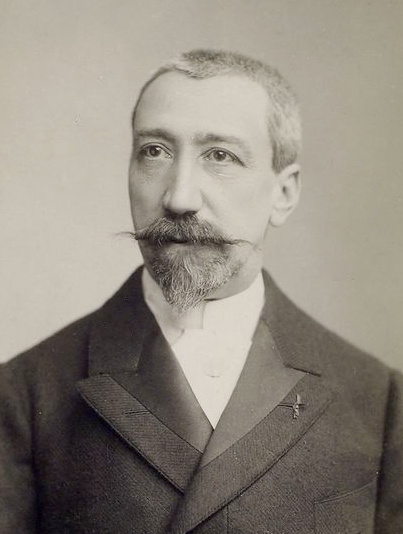

So I was surprised when Professor Jerry Coyne, in a recent post on the works of the great agnostic Robert Ingersoll (pictured above left), approvingly quoted a passage from his 1872 essay, The Gods, in which he declared that the occurrence of a miracle today would demonstrate the existence of a supernatural Deity, and then followed up with a quote from another great skeptic, Anatole France (pictured above right), whose position on the matter was precisely the opposite of Ingersoll’s!

Ingersoll: a skeptic, but an open-minded one

Here is a relevant excerpt from Ingersoll’s essay, The Gods. (N.B. All bold emphases in this post are mine – VJT):

There is but one way to demonstrate the existence of a power independent of and superior to nature, and that is by breaking, if only for one moment, the continuity of cause and effect. Pluck from the endless chain of existence one little link; stop for one instant the grand procession and you have shown beyond all contradiction that nature has a master…

The church wishes us to believe. Let the church, or one of its intellectual saints, perform a miracle, and we will believe. We are told that nature has a superior. Let this superior, for one single instant, control nature, and we will admit the truth of your assertions…

We want one fact. We beg at the doors of your churches for just one little fact. We pass our hats along your pews and under your pulpits and implore you for just one fact. We know all about your mouldy wonders and your stale miracles. We want a ‘this year’s fact’. We ask only one. Give us one fact for charity. Your miracles are too ancient. The witnesses have been dead for nearly two thousand years. Their reputation for “truth and veracity” in the neighborhood where they resided is wholly unknown to us. Give us a new miracle, and substantiate it by witnesses who still have the cheerful habit of living in this world…

We demand a new miracle, and we demand it now. Let the church furnish at least one, or forever after hold her peace.

Ingersoll was a skeptic, but at least he was an honest man, open to new evidence. Professor Coyne then went on to gleefully quote a short passage from Anatole France’s essay, Miracle, published in his 1895 anthology, Le Jardin d’Epicure (The Garden of Epicurus). In the essay, the author described a recent visit that he had made to Lourdes. His companion, upon noticing the discarded wooden crutches on display at the grotto, pointed them out and whispered in his ear:

“One single wooden leg would have been much more convincing.”

Anatole France’s 1895 essay, Miracle: a classic example of closed-minded dogmatism

The above translation is Coyne’s; he tells us that he had great difficulty in tracking down the original quote. (There are dozens of sites on the Internet where he could have found it, and the essay can also be found in the late Christopher Hitchens’ work, The Portable Atheist.) But what Coyne omitted to mention was that Anatole France then went on to add that no amount of evidence would convince him of the occurrence of a miracle, because of his prior commitment to naturalism. Below, I shall reproduce in its entirety France’s 1895 essay, Miracle, in order to give the reader an opportunity to see how philosophical rigidity can close the mind of a skeptic:

We should not say: There are no miracles, because none has ever been proved. This always leaves it open to the Orthodox to appeal to a more complete state of knowledge. The truth is, no miracle can, from the nature of things, be stated as an established fact; to do so will always involve drawing a premature conclusion. A deeply rooted instinct tells us that whatever Nature embraces in her bosom is conformable to her laws, either known or occult. But, even supposing he could silence this presentiment of his, a man will never be in a position to say: “Such and such a fact is outside the limits of Nature.” Our researches will never carry us as far as that. Moreover, if it is of the essence of miracle to elude scientific investigation, every dogma attesting it invokes an intangible witness that is bound to evade our grasp to the end of time.

This notion of miracles belongs to the infancy of the mind, and cannot continue when once the human intellect has begun to frame a systematic picture of the universe. The wise Greeks could not tolerate the idea. Hippocrates said, speaking of epilepsy: “This malady is called divine; but all diseases are divine, and all alike come from the gods.” There he spoke as a natural philosopher. Human reason is less assured of itself nowadays. What annoys me above all is when people say: “We do not believe in miracles, because no miracle is proved.”

Happening to be at Lourdes, in August, I paid a visit to the grotto where innumerable crutches were hung up in token of a cure. My companion pointed to these trophies of the sick-room and hospital ward, and whispered in my ear:

“One wooden leg would be more to the point.”

It was the word of a man of sense; but speaking philosophically, the wooden leg would be no whit more convincing than a crutch. If an observer of a genuinely scientific spirit were called upon to verify that a man’s leg, after amputation, had suddenly grown again as before, whether in a miraculous pool or anywhere else, he would not cry: “Lo! a miracle.” He would say this:

“An observation, so far unique, points us to a presumption that under conditions still undetermined, the tissues of a human leg have the property of reorganizing themselves like a crab’s or lobster’s claws and a lizard’s tail, but much more rapidly. Here we have a fact of nature in apparent contradiction with several other facts of the like sort. The contradiction arises from our ignorance, and clearly shows that the science of animal physiology must be reconstituted, or to speak more accurately, that it has never yet been properly constituted. It is little more than two hundred years since we first had any true conception of the circulation of the blood. It is barely a century since we learned what is implied in the act of breathing.”

I admit it would need some boldness to speak in this strain. But the man of science should be above surprise. At the same time, let us hasten to add, none of them have ever been put to such a proof, and nothing leads us to apprehend any such prodigy. Such miraculous cures as the doctors have been able to verify to their satisfaction are all quite in accordance with physiology. So far the tombs of the Saints, the magic springs and sacred grottoes, have never proved efficient except in the case of patients suffering from complaints either curable or susceptible of instantaneous relief. But were a dead man revived before our eyes, no miracle would be proved, unless we knew what life is and death is, and that we shall never know.

What is the definition of a miracle? We are told: a breach of the laws of nature. But we do not know the laws of nature; how, then, are we to know whether a particular fact is a breach of these laws or no?

“But surely we know some of these laws?”

“True, we have arrived at some idea of the correlation of things. But failing as we do to grasp all the natural laws, we can be sure of none, seeing they are mutually interdependent.”

“Still, we might verify our miracle in those series of correlations we have arrived at.”

“No, not with anything like philosophical certainty. Besides, it is precisely those series we regard as the most stable and best determined which suffer least interruption from the miraculous. Miracles never, for instance, try to interfere with the mechanism of the heavens. They never disturb the course of the celestial bodies, and never advance or retard the calculated date of an eclipse. On the contrary, their favourite field is the obscure domain of pathology as concerned with the internal organs, and above all nervous diseases. However, we must not confound a question of fact with one of principle. In principle the man of science is ill-qualified to verify a supernatural occurrence. Such verification presupposes a complete and final knowledge of nature, which he does not possess, and will never possess, and which no one ever did possess in this world. It is just because I would not believe our most skilful oculists as to the miraculous healing of a blind man that a fortiori I do not believe Matthew or Mark either, who were not oculists. A miracle is by definition unidentifiable and unknowable.”

The savants cannot in any case certify that a fact is in contradiction with the universal order that is with the unknown ordinance of the Divinity. Even God could do this only by formulating a pettifogging distinction between the general manifestations and the particular manifestations of His activity, acknowledging that from time to time He gives little timid finishing touches to His work and condescending to the humiliating admission that the cumbersome machine He has set agoing needs every hour or so, to get it to jog along indifferently well, a push from its contriver’s hand.

Science is well fitted, on the other hand, to bring back under the data of positive knowledge facts which seemed to be outside its limits. It often succeeds very happily in accounting by physical causes for phenomena that had for centuries been regarded as supernatural. Cures of spinal affections were confidently believed to have taken place at the tomb of the Deacon Paris at Saint-Medard and in other holy places. These cures have ceased to surprise since it has become known that hysteria occasionally simulates the symptoms associated with lesions of the spinal marrow.

The appearance of a new star to the mysterious personages whom the Gospels call the “Wise Men of the East” (I assume the incident to be authentic historically) was undoubtedly a miracle to the Astrologers of the Middle Ages, who believed that the firmament, in which the stars were stuck like nails, was subject to no change whatever. But, whether real or supposed, the star of the Magi has lost its miraculous character for us, who know that the heavens are incessantly perturbed by the birth and death of worlds, and who in 1866 saw a star suddenly blaze forth in the Corona Borealis, shine for a month, and then go out.

It did not proclaim the Messiah; all it announced was that, at an infinitely remote distance from our earth, an appalling conflagration was burning up a world in a few days, — or rather had burnt it up long ago, for the ray that brought us the news of this disaster in the heavens had been on the road for five hundred years and possibly longer.

The miracle of Bolsena is familiar to everybody, immortalized as it is in one of Raphael’s Stanze at the Vatican. A skeptical priest was celebrating Mass; the host, when he broke it for Communion, appeared bespattered with blood. It is only within the last ten years that the Academies of Science would not have been sorely puzzled to explain so strange a phenomenon. Now no one thinks of denying it, since the discovery of a microscopic fungus, the spores of which, having germinated in the meal or dough, offer the appearance of clotted blood. The naturalist who first found it, rightly thinking that here were the red blotches on the wafer in the Bolsena miracle, named the fungus micrococcus prodigiosus.

There will always be a fungus, a star, or a disease that human science does not know of; and for this reason it must always behoove the philosopher, in the name of the undying ignorance of man, to deny every miracle and say of the most startling wonders, — the host of Bolsena, the star in the East, the cure of the paralytic and the like: Either it is not, or it is; and if it is, it is part of nature and therefore natural.

Seven flawed arguments against miracles

Anatole France’s essay on miracles is riddled with flaws. The fallacy in the final paragraph, where he argues that whatever exists, must be natural, should be evident to readers, without the need for further comment.

The second great fallacy in France’s reasoning regarding miracles is that he neglects probability, and frames the issue only in terms of certitude. Even if we grant his point that science can never know all the laws of Nature and can therefore never show that an event is miraculous, the fact remains that certain events are astronomically improbable – indeed, so improbable that the only prudent conclusion to draw, if one observed them, would be that they are miraculous. A tornado blowing a house down does not strike us as remarkable, but rewind the tape, and I think that even hardened skeptics would agree that here we have a sequence of events which is so improbable that we would have to call it a miracle.

Third, if Anatole France’s argument that scientists can never know all the laws of Nature were correct, then by the same token, they could never know for sure that the universe is a closed system – in which case, France’s a priori argument against the possibility of miracles collapses.

Fourth, it might be urged by modern-day skeptics that the discovery of a Grand Unified Theory of Everything, which some physicists dream of, would allow scientists to ascertain which events are ruled out by the laws of Nature, as it would yield a complete list of those laws. But if it did that, then the scientifically verified occurrence of an event ruled out by the laws of Nature would have to count as evidence for the supernatural.

Fifth, the tired old Humean objection that no matter how strong the evidence for a miracle may be, it is always more likely that the witnesses to that miracle are either lying or mistaken, rests upon a mathematical flaw, which was pointed out long ago by Charles Babbage, in his Ninth Bridgewater Treatise (2nd ed., London, 1838; digitized for the Victorian Web by Dr. John van Wyhe and proof-read by George P. Landow). I’d like to quote here from David Coppedge’s masterly online work, THE WORLD’S GREATEST CREATION SCIENTISTS From Y1K to Y2K:

Babbage’s Ninth Bridgewater Treatise (hereafter, NBT) is available online and makes for interesting reading … Most interesting is his rebuttal to the arguments of David Hume (1711-1776), the skeptical philosopher who had created quite a stir with his seemingly persuasive argument against miracles. Again, it was based on the Newtonian obsession with natural law. Hume argued that it is more probable that those claiming to have seen a miracle were either lying or deceived than that the regularity of nature had been violated. Babbage knew a lot more about the mathematics of probability than Hume. In chapter X of NBT, Babbage applied numerical values to the question, chiding Hume for his subjectivity. A quick calculation proves that if there were 99 reliable witnesses to the resurrection of a man from the dead (and I Corinthians 15:6 claims there were over 500), the probability is a trillion to one against the falsehood of their testimony, compared to the probability of one in 200 billion against anyone in the history of the world having been raised from the dead. This simple calculation shows it takes more faith to deny the miracle than to accept the testimony of eyewitnesses. Thus Babbage renders specious Hume’s assertion that the improbability of a miracle could never be overcome by any number of witnesses. Apply the math, and the results do not support that claim, Babbage says: “From this it results that, provided we assume that independent witnesses can be found of whose testimony it can be stated that it is more probable that it is true than that it is false, we can always assign a number of witnesses which will, according to Hume’s argument, prove the truth of a miracle.“ (Italics in original.) Babbage takes his conquest of Hume so far that by Chapter XIII, he argues that “It is more probable that any law, at the knowledge of which we have arrived by observation, shall be subject to one of those violations which, according to Hume’s definition, constitutes a miracle, than that it should not be so subjected.”

Sixth, Anatole France’s snide put-down of the miracles worked by a Deity as being tantamount to “little timid finishing touches to His work,” which are required because “the cumbersome machine He has set agoing needs every hour or so, to get it to jog along indifferently well, a push from its contriver’s hand,” was also convincingly rebutted by Charles Babbage. To quote Coppedge again:

The heart of NBT [the Ninth Bridgewater Treatise – VJT] is an argument that miracles do not violate natural law, using Babbage’s own concept of a calculating machine. This forms an engaging thought experiment. With his own Analytical Engine undoubtedly fresh on his mind, he asks the reader to imagine a calculating engine that might show very predictable regularity, even for billions of iterations, such as a machine that counts integers. Then imagine it suddenly jumps to another natural law, which again repeats itself with predictable regularity. If the designer of the engine had made it that way on purpose, it would show even more intelligent design than if it only continued counting integers forever. Babbage extends his argument through several permutations, to the point where he convinces the reader that it takes more intelligence to design a general purpose calculating engine that can operate reliably according to multiple natural laws, each known to the designer, each predictable by the designer, than to design a simple machine that mindlessly clicks away according to a single law. So here we see Babbage employing his own specialty – the general-purpose calculating machine – to argue his point. He concluded, therefore, as he reiterated in his later autobiographical work Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864), miracles are not “the breach of established laws, but… indicate the existence of far higher laws.”

Babbage’s suggestion is an intriguing one, which invites the question: how exactly should a miracle be defined? Should it be defined as the violation of the laws of Nature, or should it be simply be defined as an event at variance with lower-level laws, which support the regular order of things? Perhaps the latter definition would be more fruitful. And that brigs me to a seventh flaw in France’s argument against miracles: even if he were right in saying that whatever happens, happens in accordance with some law of Nature, what he fails to realize is that this argument against supernaturalism only holds if scientific reductionism is true. In other words, France is assuming that there are no higher-level laws of Nature (perhaps known only to the Author of Nature) which govern rare and singular occurrences, and which cannot be derived from the lower-level laws which support the regular order of Nature. France has no response to the question: what is so absurd about the concept of a singular law, or more generally, a law which does not supervene upon lower-level laws?

But rather than waste time arguing about the definition of a miracle, I would argue that the more profound question is: what kind of evidence warrants belief in an Intelligent Designer of Nature, and what kind of evidence should lead us to conclude that this Designer is a supernatural Being?

I might add that Anatole France never bothered to check out the evidence for Eucharistic miracles (see also here), or for God healing amputees (see here). I would invite readers to draw their own conclusions on those matters. While I can certainly understand and respect the attitude of a skeptic who says that the available evidence for miracles is not strong enough to sway his/her mind, I have to say that a skeptic like Anatole France, who refuses to even consider the possibility that he/she may be wrong strikes very much like the Aristotelian philosophers of the 17th century who, according to popular legend, refused even to look through Galileo’s telescope, because they feared that it might falsify their theories. (By the way, that story is apocryphal – see here.)

A question for Professor Coyne: whose side are you on?

I would now like to ask Professor Coyne and my skeptical readers: whose side are you on? Do you side with Ingersoll, who would be convinced were he to witness a modern miracle? Or do you side with Anatole France, who stoutly maintains that nothing would convince him of the occurrence of a miracle? You cannot have it both ways.

Until now, Professor Coyne has always declared himself to be open to the possibility of a miracle. Science, he believes, could in principle supply strong evidence (but not proof) of the miraculous. In a November 8, 2010 post entitled, Shermer and I disagree on the supernatural, Coyne wrote:

I don’t see science as committed to methodological naturalism — at least in terms of accepting only natural explanations for natural phenomena. Science is committed to a) finding out what phenomena are real, and b) coming up with the best explanations for those real, natural phenomena. Methodological naturalism is not an a priori commitment, but a strategy that has repeatedly worked in science, and so has been adopted by all working scientists.

As for me, I am committed only to finding out what phenomena really occur, and then making a hypothesis to explain them, whether that hypothesis be “supernatural” or not. In principle we could demonstrate ESP or telekinesis, both of which violate the laws of physics, and my conclusion would be, for the former, “some people can read the thoughts of others at a distance, though I don’t know how that is done.” If only Christian prayers were answered, and Jesus appeared doing miracles left and right, documented by all kinds of evidence, I would say, “It looks as if some entity that comports with the Christian God is working ‘miracles,’ though I don’t know how she does it.” ….

Science can never prove anything. If you accept that, then we can never absolutely prove the absence of a “supernatural” god — or the presence of one. We can only find evidence that supports or weakens a given hypothesis. There is not an iota of evidence for The God Hypothesis, but I claim that there could be.

Sean Carroll on the supernatural

Professor Coyne is not alone in his rejection of dogmatic methodological naturalism. The atheist physicist Sean Carroll has candidly acknowledged that there is a possibility, in principle, that science could one day decide in favor of the miraculous, in an essay refreshingly free from dogmatism, entitled, Is Dark Matter Supernatural? (Discover magazine, November 1, 2010):

Let’s imagine that there really were some sort of miraculous component to existence, some influence that directly affected the world we observe without being subject to rigid laws of behavior. How would science deal with that?

The right way to answer this question is to ask how actual scientists would deal with that, rather than decide ahead of time what is and is not “science” and then apply this definition to some new phenomenon. If life on Earth included regular visits from angels, or miraculous cures as the result of prayer, scientists would certainly try to understand it using the best ideas they could come up with. To be sure, their initial ideas would involve perfectly “natural” explanations of the traditional scientific type. And if the examples of purported supernatural activity were sufficiently rare and poorly documented (as they are in the real world), the scientists would provisionally conclude that there was insufficient reason to abandon the laws of nature. What we think of as lawful, “natural” explanations are certainly simpler — they involve fewer metaphysical categories, and better-behaved ones at that — and correspondingly preferred, all things being equal, to supernatural ones.

But that doesn’t mean that the evidence could never, in principle, be sufficient to overcome this preference. Theory choice in science is typically a matter of competing comprehensive pictures, not dealing with phenomena on a case-by-case basis. There is a presumption in favor of simple explanation; but there is also a presumption in favor of fitting the data. In the real world, there is data favoring the claim that Jesus rose from the dead: it takes the form of the written descriptions in the New Testament. Most scientists judge that this data is simply unreliable or mistaken, because it’s easier to imagine that non-eyewitness-testimony in two-thousand-year-old documents is inaccurate that to imagine that there was a dramatic violation of the laws of physics and biology. But if this kind of thing happened all the time, the situation would be dramatically different; the burden on the “unreliable data” explanation would become harder and harder to bear, until the preference would be in favor of a theory where people really did rise from the dead.

There is a perfectly good question of whether science could ever conclude that the best explanation was one that involved fundamentally lawless behavior. The data in favor of such a conclusion would have to be extremely compelling, for the reasons previously stated, but I don’t see why it couldn’t happen. Science is very pragmatic, as the origin of quantum mechanics vividly demonstrates. Over the course of a couple decades, physicists (as a community) were willing to give up on extremely cherished ideas of the clockwork predictability inherent in the Newtonian universe, and agree on the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics. That’s what fit the data. Similarly, if the best explanation scientists could come up with for some set of observations necessarily involved a lawless supernatural component, that’s what they would do. There would inevitably be some latter-day curmudgeonly Einstein figure who refused to believe that God ignored the rules of his own game of dice, but the debate would hinge on what provided the best explanation, not a priori claims about what is and is not science.

There is much wisdom in Carroll’s words. Science cannot let itself be imprisoned by metaphysical dogmas.

More about Ingersoll: what did he believe on God and a hereafter, and what drove him to attack religion?

Before I finish, I’d like to add one more quote from Robert Ingersoll’s essay, The Gods. It’s a real pity that Professor Coyne didn’t quote this passage, as it illustrates perfectly the misplaced confidence of the skeptic:

A new world has been discovered by the microscope; everywhere has been found the infinite; in every direction man has investigated and explored and nowhere, in earth or stars, has been found the footstep of any being superior to or independent of nature. Nowhere has been discovered the slightest evidence of any interference from without.

Famous last words! Abiogenesis, anyone? And what about the fine-tuning argument? Ingersoll was at least an honest doubter. I wonder what conclusions he would draw if he were alive today.

But even Ingersoll was, it seems, the prisoner of his age. Although he expressed a willingness, in principle, to accept evidence of miracles, apparently he found the idea of a genuinely supernatural Being inconceivable. In an interview with The Dispatch (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, December 11, 1880), Ingersoll declared [scroll down to page 57]:

There may be a God for all I know. There may be thousands of them. But the idea of an independent Being outside and independent of Nature is inconceivable. I do not know of any word or doctrine that would explain my views upon that subject. I suppose Pantheism is as near as I could go. I believe in the eternity of matter and thee eternity of intelligence, but I do not believe in any being outside of Nature. I do not believe in any personal Deity. I do not believe in any aristocracy of the air. I know nothing about origin or destiny…. I believe that in all matter, in some way, there is what we call force; that one of the forms of force is intelligence.

Regarding immortality, however, Ingersoll was more open-minded. In the same interview, he acknowledged that there might be an afterlife, and in a revealing passage, he admitted that what drove him in his crusade against religion was one thing and one thing only: the doctrine, which he found deeply abhorrent, of an everlasting Hell to which the majority of human beings would be consigned:

My opinion of immortality is this:

First.- I live, and that of itself is infinitely wonderful. Second.- There was a time when I was not, and after I was not, I was. Third.- Now that I am, I may be again; and it is no more wonderful that I may be again, if I have been, than that I am, having once been nothing. If the churches advocated immortality, if they advocated eternal justice, if they said that man would be rewarded and punished according to deeds; if they admitted that at some time in eternity there would be an opportunity to lift up souls, and that throughout all the ages the angels of progress and virtue, would beckon the fallen upward; and that some time, and no matter how far away they might put off the time, all the children of men would be reasonably happy, I never would say a solitary word against the church, but just as long as they preach that the majority of mankind will suffer eternal pain, just so long I shall oppose them; that is to say, as long as I live.

I wonder what Ingersoll would make of the late Cardinal Avery Dulles’ essay, The Population of Hell (First Things, May 2003), if he were alive in the 21st century. And I wonder if Professor Coyne will be brave enough to print the foregoing passage from Ingersoll, in his weekly series over at Why Evolution Is True on the great skeptic’s views. We shall see.