|

|

|

The vast majority of people who live in Louisiana hold beliefs about the human mind and about free will which are broadly compatible with those of Darwin’s contemporary, Alfred Russel Wallace (pictured right), but diametrically opposed to those of Charles Darwin (pictured left). However, the National Center for Science Education wants Darwin’s materialistic version of evolution, which denies free will, to be taught in American high schools.

Left: A photo of Charles Darwin taken circa 1854. Center: St. Louis Cathedral, New Orleans. Right: A photo of Alfred Russel Wallace in 1862. Images courtesy of Messrs. Maull and Fox, Nowhereman86, James Marchant and Wikipedia.

(Part three of a series of posts in response to Zack Kopplin. See here for Part one and here for Part two.)

This series of posts is dedicated to the people of Louisiana, most of whom support the 2008 Louisiana Science Education Act (LSEA), which allows teachers to encourage the open and objective discussion of scientific theories, including evolution and origin-of-life theories, in high school science classrooms. The Louisiana Senate Bill 374, which was filed by Senator Karen Peterson, would take away this freedom, and require high school students to be taught the Darwinian theory of evolution which is presented in officially approved science textbooks – and no other theory.

Many people who would describe themselves as “theistic evolutionists” see Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution as compatible with their theological beliefs. Science, they would say, describes how things happen, while religion explains why they happen. Science is about the physical world, while religion is about the underlying spiritual dimension of reality, which science does not attempt to explain. Consequently, they reason, Darwin’s theory of evolution has nothing to say about the religious belief that each of us has an immortal, spiritual soul created by God, or that each of us has free will. If people want to believe these things, they can, while still remaining good Darwinists. Many Catholics, in particular, rationalize their support of Darwinian evolution in this way. About 25% of Louisiana’s population are Catholics, so I hope some of them are reading this.

The aim of this post will be to demonstrate that belief in Darwinian evolution is totally incompatible with belief in an immaterial human soul and belief in free will, in the ordinary sense of the term. I shall attempt to demonstrate that Darwinian evolution is essentially a materialistic, deterministic theory. The reason why I maintain that the Darwinian theory of evolution is essentially materialistic and deterministic has to do with what counts as a proper scientific explanation, for Darwinists.

Before I do that, however, I’d like to compare the beliefs of the people of Louisiana with those of Charles Darwin, regarding the human soul and free will. The reason why I’m doing this is a very simple one: for those readers who live in the United States, it’s your money which is funding the high schools in your state. Why should taxes paid by decent, hard-working Louisianans, or people in any other American state for that matter, be spent on the indoctrination of their children in a worldview which is diametrically opposed to the beliefs of ordinary Americans on matters of morality, not to mention religion? Common sense would suggest that’s just not right. I shall attempt to demonstrate in this post that materialism and the denial of free will – notions that most Americans would vehemently reject – are part-and-parcel of the Darwinian theory of evolution. The implications of this debate on Darwinism should be obvious enough. Anyone who thinks that students’ moral behavior will remain unaffected after they are convinced that they don’t have free will clearly has rocks in his head.

What do the people of Louisiana believe about the human soul and about free will?

Baton Rouge skyline. Courtesy of UrbanPlanetBR and Wikipedia.

Citing the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, Wikipedia lists the current religious affiliations of the people of Louisiana as follows:

Christian: 90%

Protestant: 60%

Evangelical Protestant 31%

Historically black Protestant: 20%

Mainline Protestant 9%Roman Catholic: 28%

Other Christian: 2%

Jehovah’s Witnesses: 1%

Other Religions: 2%

Islam: 1%

Buddhism: 1%

Judaism: less than 0.5%

Non-religious (unaffiliated): 8%

Looking at these figures, we can see that the vast majority of Louisianans hold beliefs about the human soul and about free will which are totally at variance with the teachings of Darwinian evolution. A solid majority of people in the state of Louisiana would accept the following three propositions:

1. Each human being has an immaterial and immortal soul, created by God.

2. Our higher mental acts – in particular, our thoughts and our free decisions – cannot be identified with movements of neurons in the brain. Rather, they are immaterial, spiritual actions.

3. Each human being has libertarian free will: that is,

(i) our choices are not determined by circumstances beyond our control, such as our heredity or environment; and

(ii) whenever we make a choice, we could have chosen otherwise.

The vast majority of Christians, as well as many Jews and Muslims, would subscribe to propositions 1 and 2. Jews, Buddhists and nearly all Christians would subscribe to proposition 3, as well as many people who would not describe themselves as religious. Darwinian evolution denies all three propositions.

But before I go on, I’d like to briefly focus on the beliefs of the Catholic Church, which is Louisiana’s largest religious community.

The teaching of the Catholic Church concerning the human soul

Curiously, there are some highly educated people who call themselves Catholics, and who are under the mistaken impression that belief in an immortal, immaterial soul is an “optional extra” which Catholics are no longer required to accept, and which the Church will quietly drop in another 50 years or so. Nothing could be further from the truth.

It is an article of faith among Catholics that each and every human soul is immaterial, that it is created immediately by God, and that it survives bodily death. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church puts it in paragraph 366:

366 The Church teaches that every spiritual soul is created immediately by God – it is not “produced” by the parents – and also that it is immortal: it does not perish when it separates from the body at death, and it will be reunited with the body at the final Resurrection.(235)

The footnote (#235) gives the following citation:

235 Cf. Pius XII, Humani Generis: DS 3896; Paul VI, CPG 8; Lateran Council V (1513): DS 1440.

The first reference is to Pope Pius XII’s 1950 encyclical Humani Generis, which states in paragraph 36 that “the Catholic faith obliges us to hold that souls are immediately created by God.”

The second reference is to Pope Paul VI’s Credo of the People of God (issued on June 30, 1968), which contains the following statement:

We believe in one only God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, creator of things visible such as this world in which our transient life passes, of things invisible such as the pure spirits which are also called angels, and creator in each man of his spiritual and immortal soul.

The third reference is to a proclamation made by Pope Leo X on 19 December 1513, at the eighth session of the ecumenical Fifth Lateran council, and ratified by that council, declaring that each human being has a unique, immaterial soul:

… [W]e condemn and reject all those who insist that the intellectual soul is mortal, or that it is only one among all human beings, and those who suggest doubts on this topic.

Well, I hope that puts to rest the canard that belief in a spiritual soul, created by God, is no longer Catholic doctrine.

Catholics make up one-quarter of Louisiana’s population. One would therefore expect them to be appalled at the very suggestion that their children should be taught a scientific theory which is avowedly materialistic and deterministic, while they are attending high school. (In case readers are wondering, the percentage of Catholic children attending parochial schools in the United States is minuscule: according to Wikipedia, only 15 percent of Catholic children in America attended Catholic elementary schools, in 2009, and among Latinos, the fastest-growing group in the Catholic Church — soon to comprise a majority of Catholics in the United States — the proportion is just 3 percent.)

I therefore find it odd that there has been a deafening silence from the Catholic Church on the question of whether high school students should be exposed to alternatives to Darwinian evolution in science classes, such as Alfred Russel Wallace’s theory, which acknowledges the reality of a spiritual realm while accepting the common descent of living organisms. I therefore hope that this post will serve as a little wake-up call to the Church hierarchy. And for those clergymen who are worried about another Galileo case, I would reply that: (a) unlike Darwin, Galileo was firmly convinced of the reality of the human soul (as I’ll show in my sixth post), and (b) a biological theory which is essentially materialistic and deterministic, and which is taught to high school science students as an established fact, will destroy the faith of the next generation of Catholics far more effectively than any public tussle between science and religion.

Why a Darwinian evolutionist cannot consistently believe in the human soul or in free will

There are two reasons why a Darwinian evolutionist is committed to a materialistic account of the human mind.

First, if you want to call yourself a believer in neo-Darwinian evolution, then you have to believe that it is an all-encompassing theory of living things, just as the atomic theory is an all-encompassing theory of chemistry. You have to believe that the theory of evolution is capable of explaining all of the characteristics of each species of organism. The theory of evolution stands or falls on its claim to be a complete biological theory. As Theodosius Dobzhansky memorably put it in a 1973 essay in The American Biology Teacher (volume 35, pages 125-129): “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” Consequently, if you believe that there are organisms on this planet, such as human beings, that possess characteristics which evolution is unable to account for, then you cannot call yourself an evolutionist, and you certainly cannot call yourself a bona fide Darwinist.

Human beings are animals. One feature which human beings possess is consciousness. If you believe that consciousness cannot be explained in materialistic terms, then you cannot call yourself a consistent Darwinian evolutionist.

The second reason has to do with the nature of a scientific explanation. As we’ll see, Darwin and his followers held that the only proper kind of scientific explanation is one that brings a class of phenomena under the scope of a universal law, which is fixed and deterministic. Any other kind of explanation is inadequate, because it fails to generate useful predictions. Darwin and his fellow evolutionists looked forward to the day when everything in Nature would be explained in the same way that scientists explain the orbits of the planets: in terms of fixed, deterministic laws.

In this post, I’m going to examine in detail what Charles Darwin wrote, in his scientific works and his private notebooks, about the evolution of the human mind. What I shall endeavor to show is the following:

(a) For Darwin, a good scientific explanation is one which appeals to physical laws, which are conceived of as fixed and deterministic;

(b) Darwin maintained that our thoughts could be explained in terms of law-governed physical processes;

(c) Darwin explicitly rejected the view that there was anything special about human intellectual capacities;

(d) Darwin viewed the difference between humans and other animals as being one of degree rather than kind;

(e) Darwin held that natural selection was fully capable of explaining the origin of human mental faculties, and actively opposed Wallace’s view that only the guidance of a Higher Intelligence could account for the origin of man; and

(f) Darwin was a determinist who maintained that human choices were also the outcome of blind natural forces, and that none of us was responsible for our actions.

N. B. In the quotations below, all bold emphases are mine, while those in italics are the author’s.

(a) For Darwin, a good scientific explanation is one which appeals to deterministic physical laws

The bodies in our solar system move according to fixed, deterministic laws. Darwin and his champion, Thomas Henry Huxley both maintained that any genuine scientific explanation should explain phenomena according to such laws. Without fixed and deterministic laws, a scientific theory is useless for making predictions. Image courtesy of NASA and Wikipedia.

In order to better grasp why Darwinism could never tolerate making a special exception for human beings, we need to understand what Darwin believed a genuine scientific explanation should be able to accomplish.

Darwin set out the conditions that he believed a good scientific explanation must satisfy in a short essay which he jotted down while he was reading selected passages from Dr. John MacCullough’s book, Proofs and Illustrations of the Attributes of God (London, James Duncan, Paternoster Row, 1837). For those who are interested, here’s the reference: Darwin, C. R. ‘Macculloch. Attrib of Deity’ [Essay on Theology and Natural Selection] (1838). CUL-DAR71.53-59. Viewers can read it here at Darwin Online.)

Darwin’s essay contains a telling passage in section 5, which succinctly summarizes why Darwin believed that the only good explanation is one which appeals to physical laws, and why he believed appeals to “the will of God” explained nothing:

N.B. The explanation of types of structure in classes — as resulting from the will of the deity, to create animals on certain plans, — is no explanation — it has not the character of a physical law /& is therefore utterly useless.— it foretells nothing/ because we know nothing of the will of the Deity, how it acts & whether constant or inconstant like that of man.— the cause given we know not the effect.

We can see from this passage that Darwin was looking for a theory of origins which explained everything in terms of physical laws, which enable scientists to predict effects from causes, in a deterministic fashion. Supernatural explanations were rejected by Darwin, precisely because they cannot yield such predictions – “the cause given we know not the effect.” Other scientists in Darwin’s time were coming around to the same view, as historian of science Ronald Numbers narrates in his essay, “Science without God: Natural Laws and Christian Beliefs” (in When Science and Christianity Meet, ed. by David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers, Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2003):

Within a couple of decades many other students of natural history (or naturalists, as they were commonly called) had reached the same conclusion. The British zoologist Thomas H. Huxley, one of the most outspoken critics of the supernatural origin of species, came to see references to special creation as representing little more than a “specious mask for our ignorance.” (Numbers, 2003, p. 279.)

Thomas Henry Huxley was the ablest and most forthright exponent of Darwin’s views, earning him the nickname, “Darwin’s bulldog.” Huxley’s remark on special creation, which is cited by Ronald Numbers in his essay, is taken from from an article entitled, Darwin on the Origin of Species, which published in The Westminster Review in April 1860. It is worth quoting the above-cited remark by Huxley in its proper context, because it perfectly illustrates Darwinian thinking on the nature of scientific explanations:

A phenomenon is explained when it is shown to be a case of some general law of Nature; but the supernatural interposition of the Creator can, by the nature of the case, exemplify no law, and if species have really arisen in this way, it is absurd to attempt to discuss their origin.

Or lastly, let us ask ourselves whether any amount of evidence which the nature of our faculties permits us to attain, can justify us in asserting that any phenomenon is out of the reach of natural causation. To this end it is obviously necessary that we should know all the consequences to which all possible combinations, continued through unlimited time, can give rise. If we knew these, and found none competent to originate species, we should have good grounds for denying their origin by natural selection. Till we know them, any hypothesis is better than one which involves us in such miserable presumption.

But the hypothesis of special creation is not only a specious mask for our ignorance; its existence in Biology marks the youth and imperfection of the science. For what is the history of every science, but the history of the elimination of the notion of creative, or other interferences, with the natural order of the phenomena which are the subject matter of that science? When Astronomy was young “the morning stars sang together for joy,” and the planets were guided in their courses by celestial hands. Now, the harmony of the stars has resolved itself into gravitation according to the inverse squares of the distances, and the orbits of the planets are deducible from the laws of the forces which allow a schoolboy’s stone to break a window.

(Huxley, T.H. 1860. Darwin on the origin of Species. Westminster Review 17 (n.s.): 541-70. The above excerpt, which is available at Darwin Online is taken from page 559. This essay is also available online in Lay Sermons, Addresses and Reviews by Thomas Henry Huxley. Elibron Classics, 2005, Adamant Media Corporation. Facsimile of the edition published by Macmillan & Co., London, 1906. Chapter XII, pp. 245-246.)

(Bold emphases mine – VJT. Note: In the passage above, I’ve modernized the spelling of “phaenomenon” to “phenomenon.”)

Finally, it is important for the modern reader to understand that for Darwin and his contemporaries, any explanation of a phenomenon in terms of physical laws had to be a deterministic explanation. As Darwin wrote in his autobiography:

Everything in nature is the result of fixed laws.

(Barlow, Nora ed. 1958. The autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809-1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his grand-daughter Nora Barlow. London: Collins. Page 87. Available online here at Darwin Online.)

Or as Darwin’s bulldog, Thomas Henry Huxley, memorably put it:

If there is anything in the world which I do firmly believe in, it is the universal validity of the law of causation.

(‘Science and Morals’ (1886). In Collected Essays (1994), Vol. 9, 121.)

Let us recapitulate here. For Darwin and Huxley, the only proper way of explaining a phenomenon scientifically is to bring it under the scope of some general natural law, which permits scientists to predict the phenomenon in a deterministic fashion. Supernatural explanations explain nothing, according to Darwin, because they do not enable scientists to predict anything.

(b) Darwin believed our thoughts could be explained in terms of law-governed physical processes

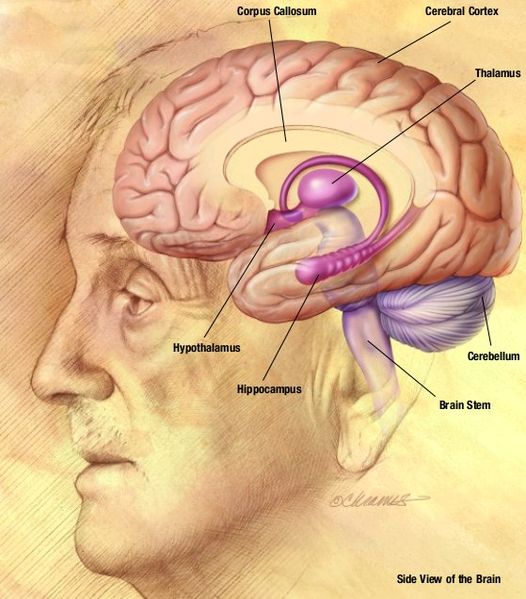

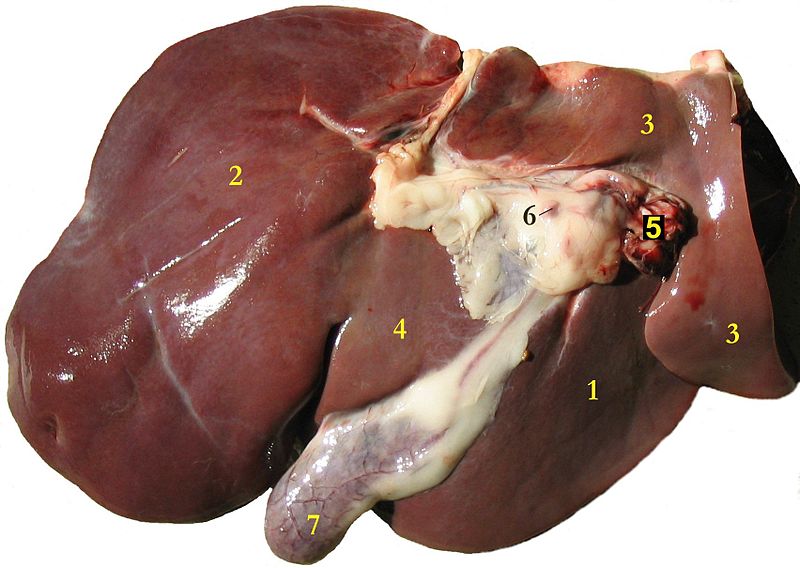

|

|

Charles Darwin shared the belief of the French physiologist Pierre Cabanis (1757-1808) that the human brain secretes thought just as the liver secretes bile. Left: Drawing of the human brain, showing several of the most important brain structures. Right: A sheep’s liver. Images courtesy of National Institute for Aging and Wikipedia.

Darwin’s Notebooks, which trace the development of his thought over time, were not published during his lifetime. Fortunately, they are now available online, after having been originally transcribed by Paul Barrett in 1974. What they reveal is that as far back as 1838, over twenty years before he published his Origin of Species in 1859, Darwin was an avowed materialist, who insisted that natural selection had to be able to account for human consciousness.

In his Notebook C: Transmutation of species (2-7.1838), Darwin espoused a mechanistic account of the human mind:

Why is thought, being a secretion of brain, more wonderful than gravity a property of matter? – It is our arrogance, it our admiration of ourselves. (Paragraph 166)

Darwin’s assertion that thought is “a secretion of brain” echoes a famous remark by the French physiologist Pierre Jean Georges Cabanis (1757-1808), who wrote in his Rapports du physique et du moral de l’homme (1802) that “to have an accurate idea of the operations from which thought results, it is necessary to consider the brain as a special organ designed especially to produce it, as the stomach and the intestines are designed to operate the digestion, (and) the liver to filter bile…” (English translation, On the Relation Between the Physical and Moral Aspects of Man by Pierre-Jean-George Cabanis, edited by George Mora, translated by Margaret Duggan Saidi from the second edition, reviewed, corrected and enlarged by the author, 1805. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, 1981, p. 116). This remark is usually cited as the pithy maxim: “The brain secretes thought as the liver secretes bile.”

In the same paragraph in Notebook C: Transmutation of species (2-7.1838), Darwin playfully scolds himself for being a materialist. He must have appreciated the humor of the situation, given that he had previously studied to be an Anglican clergyman! The mis-spellings and grammar and punctuation errors are Darwin’s:

Thought (or desires more properly) being heredetary.- it is difficult to imagine it anything but structure of brain heredetary,. – analogy points out to this.- love of the deity effect of organization. oh you Materialist! – Read Barclay on organization!! (Paragraph 166)

In his Notebook M [Metaphysics on morals and speculations on expression (1838) CUL-DAR125], which was marked “Private”, Darwin was more forthright about his materialism:

It is an argument for materialism, that cold water brings on suddenly in head, a frame of mind, analogous to those feelings, which may be considered as truly spritual. (Paragraph 20)

Not wishing to scandalize his friends, however, Darwin decided to keep quiet about his materialist views when discoursing in public. He therefore resolved:

To avoid stating how far, I believe, in Materialism, say only that emotions, instincts degrees of talent, which are heredetary are so because brain of child resembles parent stock. (Paragraph 57)

Keeping quiet about his materialism was undoubtedly a very wise decision on Darwin’s part. In 1748, the French physician, Julien Offray de La Mettrie had asserted that man was merely a machine (La Mettrie J. Leyden: Luzac; 1748. L’Homme Machine) – a claim that got him into so much trouble that he was compelled to flee abroad for his safety. In 1816, the English physician Sir William Lawrence had candidly declared his conviction that “physiologically speaking… the mind is the grand prerogative of the brain” (Lawrence W. London: Callow; 1816, An introduction to comparative anatomy and physiology), but his writings provoked an uproar, and he was pressured to recant his materialist views. After he did so, he later became President of the Royal College of Surgeons of London and Serjeant Surgeon to the Queen.

(c) Darwin explicitly rejected the view that there was anything special about human intellectual capacities

In defiance of the common view that human beings were unique, Darwin argued that there was nothing particularly special about man’s intellectual capacities. In his Notebook B: Transmutation of species (1837-1838), he downplayed human uniqueness in this regard:

People often talk of the wonderful event of intellectual Man appearing – the appearance of insects with other senses is more wonderful… (Paragraph 207)

It is absurd to talk of one animal as being higher than another. – We consider those, where the cerebral structure {intellectual faculties} most developed, as highest. – A bee doubtless would when the instincts were. (Paragraph 74)

Darwin wrote those words in 1838. Even at that time, he did not regard human intellectual capacities as lying outside the province of the laws of Nature.

(d) Darwin viewed the difference between humans and other animals as one of degree rather than kind

An ant carrying an aphid. According to Darwin, the difference in mental abilities between an ant and an aphid is much greater than the intellectual difference between a man and an ape. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Darwin’s work, The Origin of Species, was published in 1859, but Darwin’s only allusion to human evolution in this volume was his cryptic statement in the last chapter that in the distant future, “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.” It was not until 1871 that Darwin explicitly addressed the subject of human origins in his long-awaited work, The Descent of Man. In this book, Darwin argued that the difference between man and other animals was one of degree rather than kind, and that the transition from ape-like creatures to man had occurred gradually and not suddenly:

In the following passage, Darwin supports his claim that the mental faculties of humans and other animals differ only in degree by arguing that the difference in mental faculties between the higher and lower insects exceeds the mental difference between man and other mammals:

Some naturalists, from being deeply impressed with the mental and spiritual powers of man, have divided the whole organic world into three kingdoms, the Human, the Animal, and the Vegetable, thus giving to man a separate kingdom. (1. Isidore Geoffroy St.-Hilaire gives a detailed account of the position assigned to man by various naturalists in their classifications: ‘Hist. Nat. Gen.’ tom. ii. 1859, pp. 170-189.) Spiritual powers cannot be compared or classed by the naturalist: but he may endeavour to shew, as I have done, that the mental faculties of man and the lower animals do not differ in kind, although immensely in degree. A difference in degree, however great, does not justify us in placing man in a distinct kingdom, as will perhaps be best illustrated by comparing the mental powers of two insects, namely, a coccus or scale-insect and an ant, which undoubtedly belong to the same class. The difference is here greater than, though of a somewhat different kind from, that between man and the highest mammal. The female coccus, whilst young, attaches itself by its proboscis to a plant; sucks the sap, but never moves again; is fertilised and lays eggs; and this is its whole history. On the other hand, to describe the habits and mental powers of worker-ants, would require, as Pierre Huber has shewn, a large volume; I may, however, briefly specify a few points. Ants certainly communicate information to each other, and several unite for the same work, or for games of play. They recognise their fellow-ants after months of absence, and feel sympathy for each other. They build great edifices, keep them clean, close the doors in the evening, and post sentries. They make roads as well as tunnels under rivers, and temporary bridges over them, by clinging together. They collect food for the community, and when an object, too large for entrance, is brought to the nest, they enlarge the door, and afterwards build it up again. They store up seeds, of which they prevent the germination, and which, if damp, are brought up to the surface to dry. They keep aphides and other insects as milch-cows. They go out to battle in regular bands, and freely sacrifice their lives for the common weal. They emigrate according to a preconcerted plan. They capture slaves. They move the eggs of their aphides, as well as their own eggs and cocoons, into warm parts of the nest, in order that they may be quickly hatched; and endless similar facts could be given. (Chapter VI. On the Affinities and Genealogy of Man.)

Darwin was also quite explicit that the intellectual transition from ape-like creatures to man was an imperceptible one, and that the human mind had evolved gradually:

Whether primeval man, when he possessed but few arts, and those of the rudest kind, and when his power of language was extremely imperfect, would have deserved to be called man, must depend on the definition which we employ. In a series of forms graduating insensibly from some ape-like creature to man as he now exists, it would be impossible to fix on any definite point where the term “man” ought to be used. (Chapter VII, On the Races of Man.)

(e) Darwin held that natural selection was fully capable of explaining the origin of human mental faculties, and actively opposed Wallace’s view that only the guidance of a Higher Intelligence could account for the origin of man

Human and chimpanzee skull and brain. Illustrations by Dr. Paul Gervais, 1854, in Histoire naturelle des mammiferes, avec l’indication de leurs moeurs, et de leurs rapports avec les arts, le commerce et l’agriculture. Image courtesy of Vlastni fotografie and Wikipedia.

In his 1871 work The Descent of Man, Darwin argued that because human intelligence conferred a survival advantage on its possessors, the gradual improvement of intelligence in our ape-like ancestors could easily be explained by his theory of evolution by natural selection:

The case, however, is widely different, as Mr. Wallace has with justice insisted, in relation to the intellectual and moral faculties of man. These faculties are variable; and we have every reason to believe that the variations tend to be inherited. Therefore, if they were formerly of high importance to primeval man and to his ape-like progenitors, they would have been perfected or advanced through natural selection. Of the high importance of the intellectual faculties there can be no doubt, for man mainly owes to them his predominant position in the world. We can see, that in the rudest state of society, the individuals who were the most sagacious, who invented and used the best weapons or traps, and who were best able to defend themselves, would rear the greatest number of offspring. The tribes, which included the largest number of men thus endowed, would increase in number and supplant other tribes. (Chapter V. On the Development of the Intellectual and Moral Faculties during Primeval and Civilised Times.)

For those readers who may be wondering, the “Mr. Wallace” referred to in the passage above was none other than the great naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace. Part of the reason why Darwin wrote The Descent of Man in 1871 was to rebut the view, put forward by Wallace in an essay in in the Quarterly Review of April 1869, that the special intervention of a Higher Intelligence was necessary in order to account for the evolution of human beings from ape-like ancestors. According to Wallace, this Higher Intelligence had carefully directed our evolution from ape-like creatures in a manner similar to the way in which human beings breed organisms for their own special purposes, such as seedless bananas, and milch cows that produce extra milk. For Darwin, Wallace’s championing of this view felt like a personal betrayal. Darwin and Wallace had closely collaborated in developing the theory of evolution by natural selection, and at that time, Wallace had given no indications that he harbored any reservations about the theory’s ability to account for human evolution. Indeed, Wallace had even highlighted the role played by natural selection in the evolution of man in an 1864 essay entitled, The Origin of Human Races and the Antiquity of Man Deduced From the Theory of “Natural Selection”, published in the Journal of the Anthropological Society of London (Vol. 2, 1864, pp. clviii-clxxxvii), which was highly praised by Darwin.

Darwin was therefore deeply pained in 1869, when he heard that Wallace intended to publish an essay in the Quarterly Review (April 1869, pp. 359-394), arguing that the appearance of human mental faculties could not be explained in terms of blind, mechanical processes, but required the intervention of a Higher Intelligence. While he was awaiting the publication of the essay in the Quarterly Review, Darwin wrote to Wallace:

As you expected, I differ grievously from you, and I am very sorry for it. I can see no necessity for calling in an additional and proximate cause in regard to man. (Letter of Charles Darwin to A. R. Wallace, Down, April 14, 1869.)

When he finally read Wallace’s essay, which argued that natural selection, left to itself, would only have given human beings a brain “a little superior to that of an ape,” Darwin was so appalled that he scribbled “NO!!!!” in the margin and even underlined the word “NO” three times. Darwin later expressed his disappointment over Wallace’s views on the origin of man in a personal letter, and chided him for back-sliding from his earlier enthusiastic support of natural selection as the explanation of human mental capacities: “But I groan over Man – you write like a metamorphosed (in retrograde direction) naturalist. And you, the author of the best paper that ever appeared in the Anthropological Review! Eheu! Eheu! Eheu! — Your miserable friend, C. Darwin.” (Letter of Charles Darwin to A. R. Wallace, Down, January 26, 1870. In The correspondence of Charles Darwin, volume 18: 1870. Edited by Frederick Burkhardt, James A. Secord, Sheila Ann Dean, Samantha Evans, Shelley Innes, Alison M. Pearn, Paul White. Cambridge University Press 2010. See page 17.)

The striking differences between Wallace’s and Darwin’s views on the origin of human mental faculties led to an intellectual rift between them that was never healed. Although the two scientists remained on friendly terms, Wallace was no longer part of Darwin’s “inner circle.”

(f) Darwin was a determinist who maintained that human choices were also the outcome of blind natural forces

An American judge talking to a lawyer. According to Charles Darwin, none of us is responsible for our actions. Criminals should be punished solely in order to deter others from committing crimes, but they are not to blame for what they do. Image courtesy of maveric2003 and Wikipedia.

As we have seen, Darwin made no secret of the fact that he believed natural selection could account for our distinctively human traits. We have also seen that for Darwin and his evolutionist contemporaries, any good scientific explanation of a phenomenon (such as human consciousness) had to be a deterministic one, which brought the phenomenon under the scope of some universal scientific law.

From the foregoing premises, the reader might deduce that Darwin did not believe in libertarian free will, or the view that our choices are free from determination, and that whenever we make a choice, we could have chosen otherwise. During his lifetime, however, Darwin was extremely guarded on the subject of human free will, not wishing to alarm the masses with his views on the subject. For this reason, he said little about free will in his published writings. However, his private notebooks reveal that as far back as 1837, Darwin was a thorough-going determinist.

On the 15th of July, 1838, Charles Darwin began a private notebook which he labeled as “M”, in which he intended to write down his correspondence, discoveries, musings, and speculations on “Metaphysics on Morals and Speculations on Expression”. To this day, the contents of the notebook are little known, among the general public.

On page 27 of that notebook, he expressed his skepticism regarding free will, and suggested that all of our actions (and, by extension, our thoughts and intentions) are the result of our “hereditary constitution” and “the example…or teaching of others”:

The common remark that fat men are goodnatured, & vice versa Walter Scotts remark how odious an illtempered fat man looks, shows same connection between organization & mind.—thinking over these things, one doubts existence of free will every action determined by hereditary constitution, example of others or teaching of others.— (NB man much more affected by other fellow-animals, than any other animal & probably the only one affected by various knowledge which is not heredetary & instinctive) & the others are learnt, what they teach by the same means & therefore properly no free will.

(See Darwin’s Notebook M, pp. 26-27. [Metaphysics on morals and speculations on expression (1838)]. CUL-DAR125.- Transcribed by Kees Rookmaaker. (Darwin Online, http://darwin-online.org.uk/))

Darwin was a consistent determinist. In his other metaphysical writings from that period (c. 1837), Darwin made it clear that he did not really regard human beings as morally responsible for their good or bad choices. He also held that criminals should be punished solely in order to deter others who might break the law:

(a) one well feels how many actions are not determined by what is called free will, but by strong invariable passions — when these passions weak, opposed & complicated one calls them free will — the chance of mechanical phenomena.— (mem: M. Le Comte one of philosophy, & savage calling laws of nature chance)…

The general delusion about free will obvious.— because man has power of action, & he can seldom analyse his motives (originally mostly INSTINCTIVE, & therefore now great effort of reason to discover them: this is important explanation) he thinks they have none.—

Effects.— One must view a wrecked man like a sickly one — We cannot help loathing a diseased offensive object, so we view wickedness.— it would however be more proper to pity them [than] to hate & be disgusted with them. Yet it is right to punish criminals; but solely to deter others.— It is not more strange that there should be necessary wickedness than disease.

This view should teach one profound humility, one deserves no credit for anything. (yet one takes it for beauty & good temper), nor ought one to blame others.—

(See Darwin’s Old and USELESS Notes about the moral sense & some metaphysical points written about the year 1837 & earlier, pp. 25-27. For original transcription, see Paul Barrett, et. al., Charles Darwin’s Notebooks, 1836-1844, New York: Cornell University Press, 1987, p. 608.)

Summary of Darwin’s views

We have seen that Darwin believed that his natural selection could explain the emergence of man from ape-like ancestors by a gradual process, and that natural selection could account for the entire gamut of man’s mental faculties. However, natural selection is a physical process, which operates in a deterministic manner. Thus there is no room in Darwin’s view of evolution for an immaterial soul, or for a mysterious human capacity to make undetermined choices.

To sum up: if you accept Darwinian evolution, you have to be a materialist and a determinist. In my fourth post, I’m going to produce my list of twenty-one Nobel Laureate scientists who rejected these beliefs.